On a hot afternoon, just hours before the trailer for this month’s Halloween sequel is to be released, Jason Blum is running late. He’s finishing a meeting with actor and director Jason Bateman, and when Blum spots me waiting in his hallway he offers us both a tour of his office. In previous lives this Midcentury Modern building—in a dodgy pocket of L.A. on the edge of Koreatown—was an architect’s office, the headquarters of Cat Fancy magazine, and a marijuana dispensary. Now there are on-site editing facilities, casting offices, and a screening room with a vintage candy machine. Blum bought the space five years ago, he says, “because it was cheap.” But if it was then, it’s not anymore.

Blum is the founder and CEO of Blumhouse, the film industry’s go-to production company for scary movies. Blumhouse has been responsible for more than $3 billion in global box office over the past decade, thanks to such horror franchises as Paranormal Activity, The Purge, and Insidious—plus surprise hits like the Oscar-winning Get Out. But unlike his Tinseltown competitors’, Blum’s business is built on restraint. He makes movies for $5 million or less by promising top-tier talent a share of the profits.

Today Blumhouse has more than 40 full-time employees, and the building is bursting at the seams. The company has pushed further into television following the success of HBO’s The Jinx, and Blum is at work on a miniseries about late Fox News chairman Roger Ailes and an anthology horror series for Hulu. He also has something like 48 movies in development and 12 in production; you’d be hard-pressed to find a hot entertainment property he is not somehow involved with. You can see the Hollywood sign from the building’s roof deck, but just barely, which, Blum says, is how he likes it.

As we step outside and head toward Blum’s second building, just down the street, Bateman surveys the scene and mutters, “I feel like there was an afterhours club I used to go to down here.”

At 49, Jason Blum is in great shape. He’s dressed in white pants, expensive sneakers, and a short-sleeve collared shirt; the veins of his CrossFit-toned biceps look as if they’re desperately trying to escape from his arms. We’re seated in his office, which is dark and cool and full of totems from his wide-ranging career.

In no particular order, there’s a glass eyeball (a gift from Barry Diller), a toy Wal-Mart shopping cart he took from that company’s corporate office after a meeting about a Benji reboot, and a photo of Ethan Hawke, one of the first friends Blum made in New York. Shortly after graduating from Vassar in 1991, Blum ran Hawke’s theater company, Malaparte, and the two would race around Times Square trying to sell $10 theater tickets to tourists.

Blum may be the king of low-budget horror, but he comes from highbrow roots. He is the son of influential art dealer Irving Blum, whose Ferus Gallery gave Andy Warhol his first West Coast solo exhibition in 1962. Jason’s middle name is Ferus, and the gallery’s history informed his taste and his soul. It’s impossible to understand Blumhouse without going back to, well, Blum’s house.

“My dad was a massive risk-taker,” Blum says. “He had no money and he really bet on himself, which is what we do.”

Blum isn’t kidding. How’s this for a cocktail party story: Warhol’s first show at Ferus included the 32 paintings in the “Campbell’s Soup Cans” series, displayed at eye level, as in a grocery store. Warhol was not well known at the time, and the gallery was able to sell only five or six of the paintings. But before they could be delivered, Irving decided the works belonged together, so he convinced the buyers (one of whom was Dennis Hopper) to sell them back.

Then Irving called Warhol and told him he wanted to buy all 32 paintings himself. Warhol agreed to sell them to him for $1,000—total—and he let him pay the fee over 10 months. “It was tough for me to put the money together!” Irving says today. “My rent was $75 a month.”

When Jason was a kid, his dad was living in New York, and the Soup Cans hung in his living room on the Upper East Side—all 32 paintings, in four rows of eight. When he stayed at his father’s, Jason would sometimes sleep on the sofa beneath the Warhols.

It was a childhood immersed in art history—in real time. His mother Shirley Neilsen was an art historian and professor at the State University of New York in Purchase and one of the co-founders of Ferus. (Blum’s parents split when he was four years old; he lived with his mother in Dobbs Ferry, in Westchester County, during the school year, and with his father on holidays and in the summer.)

“Roy Lichtenstein taught me how to play chess at his house in Southampton,” Blum says casually. “I was 10 or 11 years old. He had a studio on his property, and my dad would go look at the paintings.”

Ellsworth Kelly, Donald Sultan, and Bryan Hunt were all mainstays of Blum’s childhood. Dennis Hopper’s daughter Marin was his babysitter. Jasper Johns gave him a series of watercolor paintings when he was born; they now hang in his apartment in downtown Los Angeles. Irving was not the type of father who came to his son’s school baseball games, “but he did something else that was great,” Jason says. “He took me wherever he went. He treated me like an adult when I was nine.”

That’s the storybook version. “Jason was raised from the age of four by a single working mother in Dobbs Ferry,” his mother says. “When visiting his father in the city, he did meet many artists, but this was not at all his normal world.” Her memories of Jason’s childhood sound more like Stranger Things than an art apprenticeship.

Fittingly, she remembers that her son, whom she calls Jay, was always obsessed with Halloween. “At about age six,” she recalls, “he said he wanted to be ‘Bloody Bones.’ We got out the papier-mâché and went to work on bone making and then happily bloodying. He was definitely born to horror.”

Blum is often called a modern-day Roger Corman, the cinematic pioneer of micro-budget horror movies. In September, Harvard Business School published one of its famous case studies on Blum’s practices, declaring that Blumhouse, which launched in 2006, was “responsible for 13 of the top 25 most profitable films in the last five years in the U.S. when measured by box office grosses as a percentage of production budgets.”

In 2014, Universal signed a virtually unprecedented 10-year first look deal with the company; according to reports, Blum can greenlight any film he wants with a budget under $5 million—as long as it’s a genre movie.

Blum was entrepreneurial from the start. He went to boarding school at Taft, in Connecticut, then to Vassar, where Noah Baumbach was his roommate. Next up was a brief stint in Chicago, where Blum flirted with being an actor, before he moved to New York to produce Baumbach’s first film, Kicking and Screaming. Blum refers to that time as “romantic.” He was living in Marin Hopper’s rent stabilized one-bedroom in Greenwich Village, paying $800 a month, working at a small production company, and running Hawke’s theater company.

Whether consciously or not, he was trying to recreate the artistic social circle his father and mother enjoyed in New York.

He later landed a job as an acquisitions executive at Miramax, where he optioned the book The Reader (in the film of which Kate Winslet won an Oscar) and bought the script for The Others, which would help cement Nicole Kidman’s status as a star. This was the heyday of Miramax and the height of Harvey Weinstein’s dominance. Blum says he wasn’t aware of Weinstein’s sex crimes, though Weinstein did once throw a lit cigarette at him over a failed deal.

Those years were educational in other ways: Blum learned “what I would do differently if I ever had my own company,” he says. He promised himself that if he were ever lucky enough to have his own company, he would choose his battles and support his artists. David Gordon Green, who directed Halloween, says that’s not just spin. “Blum doesn’t have the scare tactics that a lot of Hollywood producers try to employ,” he says. “Like, ‘I know better than you.’ There’s never an ultimatum.”

Blum left Miramax in 2000 to produce films independently, but he acknowledges that he was haunted by the memory of his father’s success. “I felt the weight of it, definitely,” he says. “I was certainly competitive with it.” His answer to his dad’s Warhol’s Soup Cans was Paranormal Activity, a 2009 haunted house film in which the ghosts are caught on surveillance cameras.

The movie was made for $15,000 and was rejected by every studio in town—sometimes twice. Blum hung on for three years, until DreamWorks agreed to screen it for a test audience. The crowd went wild. The studio decided to release the film, and Paranormal Activity made nearly $200 million worldwide, becoming one of the most profitable movies of all time. It has spawned five sequels.

When Irving Blum is asked if he has seen any of the Paranormal Activity films, he laughs. “I’ve read the reviews.” For her part, Shirley says, “I saw the first one and was not frightened.”

Blum walks to a screening room to show me the trailer for Halloween, which I have already seen and found plenty scary. Afterward he is practically bouncing down the hallway with excitement. He tells me he doesn’t care if he’s known as the micro-budget horror guy. “I kind of enjoy it,” he says. But it’s hard to shake the sense that he still has something to prove, perhaps to the very A-list crowd he thumbs his nose at. When he’s asked about the Roger Corman comparisons, his pulse quickens.

Corman cranked out frights on the cheap, but he wasn’t known for betting on artists. Blum, by contrast, is giving directors like Jordan Peele and Damien Chazelle the cash to make provocative work. If anything, Blum aspires to be more like Scott Rudin, the prolific producer behind Aaron Sorkin’s upcoming stage adaptation of To Kill a Mockingbird and movies like Lady Bird. (Blum was an investor in Sorkin’s Broadway production of Three Tall Women.)

He’s developing a project with Dee Rees (writer and director of Mudbound), and Focus Features will launch an Oscar campaign for Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman, which Blum produced with Peele.

“I think Corman had his business and his passion separate,” Blum says. “I’m not wearing two hats. Whiplash is a real Blumhouse movie.” He’s certainly working harder than anyone with his level of success needs to. He famously converted a Chevy Astro van into a mobile office so he could work while stuck in traffic. (He has since upgraded to a Ford Transit 250 van, which he has outfitted with two large flat-screen televisions.)

When asked about his motivation, he thinks for a moment and then deflects the question. “My dad’s motivation is probably clearer to me than my own. My dad is not a very emotive person, but he’s very emotive about art. It may be the only thing he’s emotive about, in a funny way.”

Asked the same question, Irving Blum answers unequivocally: “The same thing that motivates me motivates Jason. It’s really about passion.”

If there’s one way that father and son differ, both will agree it comes down to parenting. “He’s not similar to me,” Irving says with a smile. “He’s more passionate about the kids than I recall ever being. He’s got this other activity, but somehow he doesn’t let it stand in his way.”

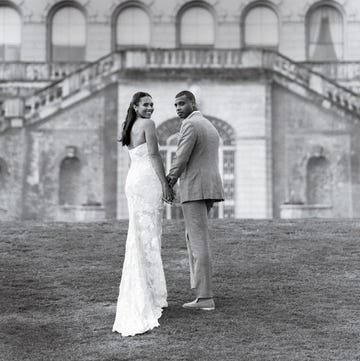

In 2012, Blum married Lauren Schuker, who had been a reporter for the Wall Street Journal; the two sold Blum’s Hollywood Hills bachelor pad in 2015 after the birth of their daughter Roxy and moved to a high-rise downtown, from which Blum can walk to a nearby multiplex. (The couple welcomed a son, Booker, this year.) Artworks by Jasper Johns and the sculptor Adam McEwen are displayed in the apartment.

Irving and his wife Jackie still advise Jason on new artists worth investing in, “when I can get his attention,” Irving says. “He’s very busy!” (Jason counters: “If my dad tells me something is good, I always buy it.”) When asked what he learned about marriage from his parents, Jason says, “I learned to wait. I didn’t get married until I was 41 years old.”

If taste in Halloween costumes is any indication, Blum and Schuker seem well matched. Last year he dressed up as Ivanka Trump—in a pink sheath dress—and she donned a military flak jacket, a reference to Jared Kushner’s much-mocked Instagram post from a Middle East trip. When asked what he might dress up as this year (Michael Myers, perhaps?), Blum thinks about it for a second and then says, “Maybe Sarah Huckabee Sanders. I’m leaning in that direction.”

This story appears in the November 2018 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW