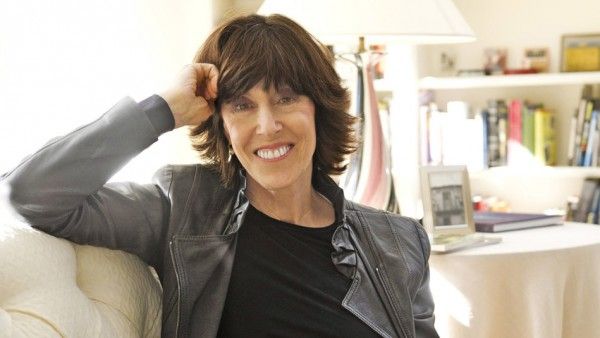

In his feature debut, Everything Is Copy, Nora Ephron: Scripted & Unscripted, writer-director and New York Times reporter Jacob Bernstein examines the fine line between professional ambition and personal loyalties and offers a candid, moving portrait of his famous mother who died in 2012. The documentary features illuminating interviews with many of her friends, family and close professional colleagues – from Meryl Streep, Tom Hanks, Rob Reiner, and the late Mike Nichols to all three of her sisters and both of her ex-husbands. Ephron’s witty, incisive essays are brought to life in dramatic readings by Lena Dunham, Reese Witherspoon, Rita Wilson and Gaby Hoffman who considered her a pioneer, mentor and friend.

Ephron was one of America’s leading literary voices and a prolific writer whose trenchant observations were distinguished by their caustic honesty and smart humor. She believed that being a writer meant turning the bad things that happened to you into comedy, and she could be ruthless when it came to telling the best story. No one was spared – not her parents, her former bosses, or her spouses. Ephron became one of the industry’s most successful writer-directors, earning Academy Award nominations for her work on Silkwood, When Harry Met Sally, and Sleepless in Seattle. Her final work, the Tony Award nominated play, Lucky Guy, was based on the life of Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Mike McAlary and marked Hanks’ Broadway debut.

In an exclusive interview with Collider, Bernstein talked about what inspired him to do a documentary about his mother’s life, why these were the right people to help tell her story, what he learned about her through the interviews, what surprised him most about her career, how her mantra of “everything is copy” became the documentary’s investigative through-line, what made her voice so distinctive, her brave but very private battle with leukemia, the most challenging aspects of making the film, why he loved the directing experience, the creative contributions of DP Bradford Young, editor Bob Eisenhardt, and co-director Nick Hooker, the dynamics of cultural journalism today, and how he looks forward to doing another documentary.

Check it all out in the interview below:

How did this project first come together for you?

JACOB BERNSTEIN: I had obviously seen this rich spate of cultural documentaries that had come out in the last few years between 2008 and 2012. There was the Joan Rivers movie (Joan Rivers: A Piece of Work), the Bill Cunningham documentary (Bill Cunningham New York), and the Valentino movie (Valentino: The Last Emperor). One of the things that I felt about many of the ones that I saw, particularly Joan Rivers and The Kid Stays in the Picture, was that they were fundamentally about a rise, a fall, and a comeback and that that architecture lent itself very naturally to my mother’s story. That even if the divorce wasn’t a fall exactly, it was the pivot point in the middle of her narrative. I was interested after she died in asking certain questions about what it is to be a writer, what it is to make the personal public, what do you gain from that, and who’s getting swiped at the same time that you’re doing that.

I went to go do a piece on a woman named Lisa Immordino Vreeland who had done the Diana Vreeland movie. She’s married to Diana Vreeland’s grandson. I said at the end, “What are you doing next?”, and she said, “Well I’m doing a movie on Peggy Guggenheim, but there is one thing I would potentially put in front of it: Nora Ephron.” I said, “Well, there’s someone in front of you.” That was the moment where I said for the first time, “I’m thinking of doing this.” I can’t remember if I said to Lisa, “It’s me.” I think she thought I meant another documentarian. Then, I went to Graydon Carter and he said we should go to HBO. I knew to go to him. Alessandra Stanley, who is a friend at the New York Times, sent me to him. Then, it moved pretty quickly.

Was making a documentary about your mother’s life a passion project for you even before she passed?

BERNSTEIN: No. I don’t think my mother ever would have agreed to do a documentary before she died. Although maybe she would have. No, I don’t think I would have written about her while she was around, except maybe in a novel as a secondary character. But after she died, I certainly felt that it was a profound experience. If you’re a writer and you have a profound experience, and a profound experience that people are curious about, it’s a shame not to try to make the most of it creatively. I totally was aware that if I didn’t write about it, my aunt Delia was going to write about it, and I wanted to get something down. Beyond that, and I’m telling you more than perhaps I should, there was also the issue of promoting the play (Lucky Guy) at that point. She wasn’t going to be around to promote it. I began through that piece also to uncork some of the stuff about how she was finding her own story in somebody else’s narrative. Then, I knew almost immediately when I began to think about what this doc would be, that it would be Everything Is Copy, that it would be how the personal life is mirroring or deviating from what’s happening in what she’s written, and how she was processing that and using it.

How hard was it to get a project like this to the place to make it all happen?

BERNSTEIN: Getting the financing was fairly easy on this. We were lucky. Graydon immediately thought that it was a good idea, and Sheila Nevins at HBO had been sniffing around this, and Susan Lacy who had just gone there from American Masters was interested in doing a doc. So, there was an appetite for it. Then, I think that because I was her son and because I was a journalist with not a terrible career, when I said, “I’m going to do this,” they went, “Okay.”

What aspects of making this film did you find the most challenging?

BERNSTEIN: Certainly, the negotiation with my father was an emotionally taxing thing, and it went on for quite a long time. Once he was there, it was fine. It went on in some ways longer than I wanted it to. I think the most challenging aspect of doing the film perhaps was how I was going to piece into it without overwhelming it and how to do that organically.

In terms of the interviews and dramatic readings, why were these the right people to help tell your mother’s story and reveal aspects of her life?

BERNSTEIN: They were the ones who knew her the best and who worked with her the longest. One of the things that was tricky to figure out was which celebrities to use and which ones not to. We became very aware that using celebrities who don’t really know the person that well can have a really bad effect on the audience and on your critics. In some places, there might have been a reason to have someone like a Tina Fey or Amy Poehler talk about what her influence is among this younger group of women comediennes like Amy Schuler, or Whitney Cummings, or any number of young female comics. The problem is that the more you do that, the more upset a certain portion of the audience becomes because it looks like the optics of it aren’t good. It begins to look like how many celebrities could I get into the room. So, it became a matter of using them sparingly and where they were most necessary and using myself sparingly and where most necessary. I hope that when this comes out that we won’t have a lot of people saying that it feels like a narcissistic episode.

How difficult was it to get everyone to participate?

BERNSTEIN: A lot of her friends were pretty inclined to do it because they loved her and it was me doing it. But, I don’t think anybody thought, “My friend has died. My sister has died. My ex-wife has died. Let’s go and do a movie about her.” I think I was slightly more gung ho than everybody else was about it. Certainly, my father had deep reservations about it, and that took two years to work through really. He had reservations for good reasons that this could easily have been a well-intentioned but misguided thing in which the son of a famous writer inserts himself clumsily into her narrative. He’s also in a happy marriage and it’s 30 years later. It’s more than 30 years. Who wants to revisit this moment that, for him, was not exactly triumphant? So, that was difficult. And then, Nick (Ephron’s third husband, writer Nicholas Pileggi) didn’t want to be in it, but that was kind of simple in some ways. He participated in all sorts of other ways. But, my brother (Max Bernstein) obviously didn’t and I get asked about that. My brother had a really private relationship with my mother. He’s a musician. He’s not a memoirist. He’s not a journalist. He doesn’t live this idea that everything is copy. I think he also was put in the position that an act of loyalty to me was going to be a potential act of disloyalty to my father. It was what it was.

Was there anything they revealed in their interviews that surprised you?

BERNSTEIN: The thing that surprised me the most was that she had managed to get as far as she did having whacked as many people as she did. Now we live in an era where it’s much more difficult, both as a journalist and as a human being, to make enemies in significant number and to be outspoken -- the speed at which somebody becomes Dave Chappelle or Kanye West or Alec Baldwin. I mean, some of those guys have rage issues. Maybe all of them do. But I do think that we live in a much more corporate era, and because journalism is under attack basically, it’s just much harder to actually say something about somebody. The circumstances in which we meet people as journalists are much more constricted. You don’t follow people for weeks at a time anymore. You interview them in circumstances like this. It’s not an enviable state. I think that in some ways the cultural journalism, the dynamics of this, mirrors what’s going on in politics. If you look at that Command Center that they had in Iraq, the charade of all of that, there is so much more pretending an intimacy, and at the same time, there’s so little. I’m going off a little bit, I guess, but I was really surprised at how many people she managed to stick it to on the way up without having it cause her downfall. That was remarkable to read through. And certainly, I learned a lot about the divorce.

There’s an investigative through-line in the documentary about why your mother kept her declining health so private towards the end despite her life-long mantra of “everything is copy.” Why do you think she did that?

BERNSTEIN: I think, for her, “everything is copy” was a way to emerge victorious. She really believed this mantra of “be the heroine of your life, not the victim.” How do you tell people that you have this thing without becoming the victim? How do you not become the person that everybody says, “How are you? How are you feeling?” Then, they start giving you unsolicited treatment options and “You should call so and so.” Beyond that, there were pragmatic reasons for not telling people, too. I do think that she wouldn’t have been insurable on a movie had she disclosed this. But, I don’t really think that was the reason. I think that the reason was more philosophical. She saw that the way to remain in control and to have life stay as normal as possible was in this way to recede a little bit. She was at a point as a writer where she was now sophisticated enough to find her experience in someone else’s story and to find her emotional through-line in theirs. That’s part of what Lucky Guy afforded. If you read the books she wrote, they are sprinkled with trenchant observations about mortality and the end.

What made your mother’s voice as a writer and a filmmaker so distinctive?

BERNSTEIN: I think that she had an ability to find the details. She had a very good sense of detail. What Rob Reiner says is partly accurate about the differences between men and women. That was part of it. But, I think it’s the sense of detail surrounding that and taking the smallest thing, whether it’s Tom Hanks scooping that garnish out of the bowl in You’ve Got Mail and Meg Ryan says, “That is a garnish.” And The Godfather versus Jane Austen, that men love The Godfather and quote it all the time, and women are always quoting Jane Austen. She took these details and she sprinkled them throughout her movies. So, you had something that was both quite palatable to a large number of people, but also had very sophisticated observations about people. At the same time, I think that the optimism of these movies felt to certain people like a betrayal of who she had been when she was younger. You know, what happened to this caustic comedienne who told it like it was and all of that? I think people change some.

Can you talk about the contributions of your creative team and how they helped you realize your vision?

BERNSTEIN: Bob Eisenhardt (the fim’s editor) had done the Valentino film. That was a movie about these two larger-than-life comic characters with plastic surgery and so much money. He had taken these people who were ripe for being lampooned, and he found this tender love story underneath. I felt that he was the right person to help steer this thing that was going to be about a comic writer who also had a sad final act in some ways, and amidst all of these questions about what it means to be a writer, and what is gained by that and what is lost. I thought that he got both humor and heartbreak. I felt very confident with him. Bob is naturally very calm. He’s not that verbal. I’m a little bit more type A and manic in certain ways. I thought that the partnership would work well.

The DP was a guy named Bradford Young who did Fruitvale Station and he did Selma. He hadn’t done Selma yet. He was found by Carly Hugo, who was one of our producers. We knew immediately that Brad was going to set the look of the film and that he then wasn’t going to be there for the duration, because no DP who is as skilled as he is, is working on a documentary for a year. He’s getting bigger jobs. He had a team of people who took over and knew how to execute the shots which have a kind of Juergen Teller-y, a little bit of Bert Stern in them. He does very good work.

Then, Nick Hooker, who’s the co-director, was sort of the visuals guy, because we had this roving cast of DP’s and my experience is all narrative. Nick had no real narrative experience. I didn’t really have visual experience. So, he was helpful in that way. But, the title is slightly misleading, because Bob was really the person who – to the degree that there was a co-pilot – the editor is really the person that you do this with. And that was that.

How long was the first cut?

BERNSTEIN: The first cut was about 100 minutes. I was a Nazi about cutting down. I did not have that thing that filmmakers have of wanting it to be longer than it should be. I have other shortcomings as a filmmaker that perhaps need to be worked out, but I had actually gone on Netflix and iTunes and I had looked at the length on the Joan Rivers film, on the Diana Vreeland film and Bill Cunningham, and on a whole bunch of them, and almost invariably they were right around 87 minutes. So, I was really determined that we were going to come in under 90. I think we live in an epidemic of movies that are longer than they should be and beautiful, ambitious films that don’t work as well as they should simply because the directors got too addicted to their own footage and lost sight of the overall narrative. I think length is tremendously important.

How do you feel the final film compares to what you originally envisioned?

BERNSTEIN: I’m pretty happy with the final film. It certainly is the examination that I set out to do. There are certainly things within it that I think could work a little bit better than they do. There are certainly places where I wish there was a little bit more detail in them. It would be nice to have my stepfather in there. It would have been nice to have my brother in there. There are places where I wish we would have gotten a few more anecdotes. I wish Gloria Steinem had said yes. She didn’t, and there’s a reason for that. I think Gloria Steinem felt she got swiped. It’s never perfect.

What did you learn about your mother in the process of making this?

BERNSTEIN: I started off thinking that my mother was more complicated than I am, because she was able to accomplish as much as she did. I presumed that there was this extra ingredient beyond even intelligence or any of that that gave her the ability to do what she did. I think that my mom in a certain way was simpler, but not simpler intellectually. She has a few IQ points on me. I feel pretty confident about that, and I don’t feel insecure about it or ashamed of it. But, I think that she went to bed relatively unencumbered by the ambivalence that can keep a person from accomplishing some of the things that they ought to accomplish. There was something about her constitution and the self-confidence that she had that was fundamentally unique. I mean, she didn’t have any self-destructive attributes. I went in thinking that was normal, and I walked out thinking that that was extraordinary. That’s actually rare. I don’t think most people are drug addicts. I don’t think most people are depressives. But, most people are something. Most people’s serotonin doesn’t quite work the way that it should. Hers worked the way that it should. So, I think that made her rare.

How did you find the directing process?

BERNSTEIN: I loved it. I mean, I think there were certainly moments where my self-confidence wavered. Particularly, about half way in, we were getting a lot of interviews where people were saying the same thing over and over again. Then, it was sort of, “Oh god, what if everybody gives us an interview where all they talk about is, ‘Nora referred me to my doctor and she told me to do this.’” All you got was one thing. So, it was scary, and the personal component of it was scary, but the experience of it is, you know, you’re making a movie. It’s incredible. And, the subject and the access that I had and the creative partners that I had were remarkable. It was nice also that I would be working on something at the New York Times and then I would sneak out and go edit. It would be a break from that. The two things complemented each other relatively well.

What’s next for you that you’re excited for audiences to know about?

BERNSTEIN: Well, I’d like to do another film. I’m not quite sure what it will be right now. But I certainly want to do another one of these badly, and I’d like to do another doc. I don’t want to move right into narrative fiction, not immediately.

Everything is Copy, Nora Ephron: Scripted & Unscripted debuts March 21 exclusively on HBO. Check out the trailer below.