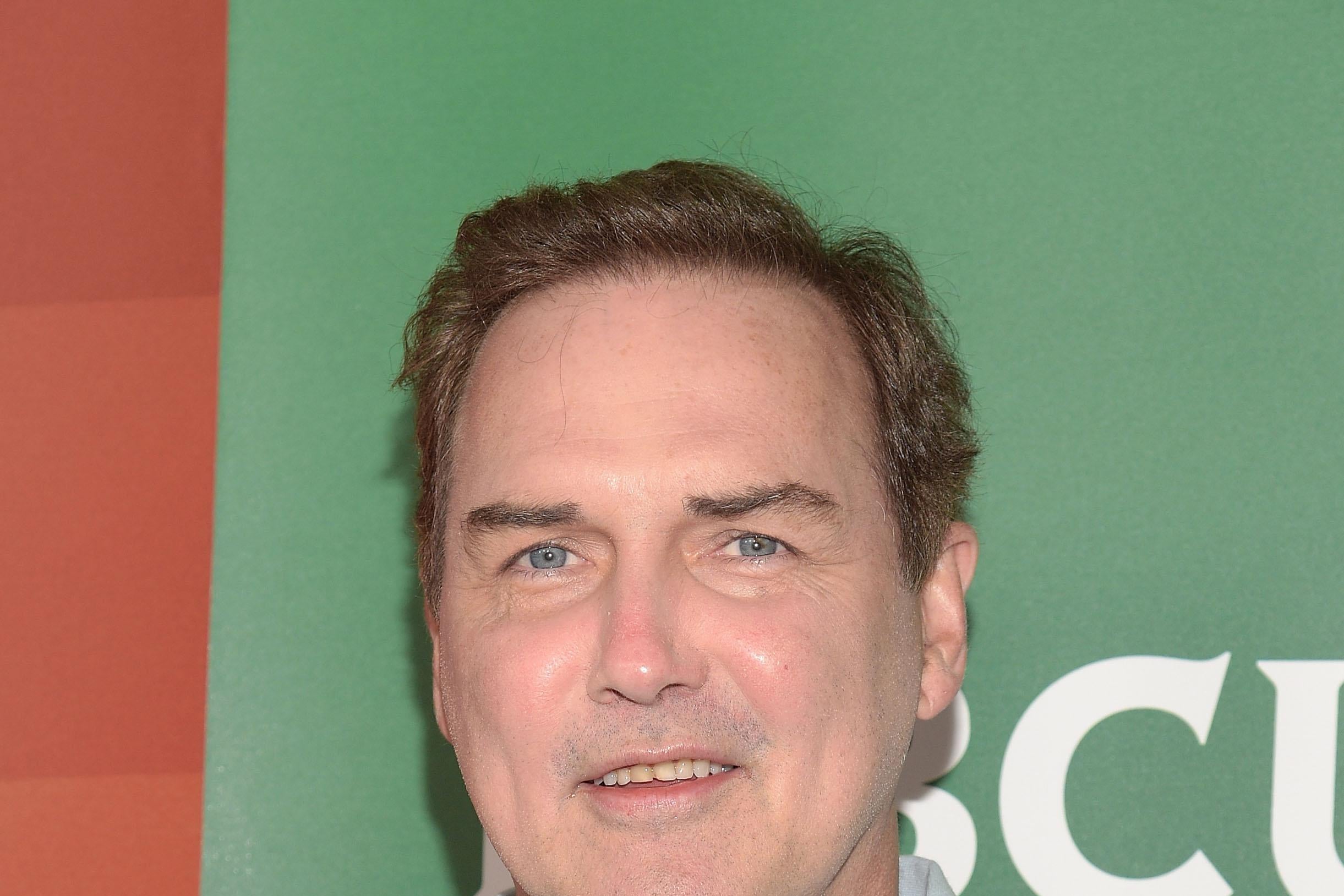

All across the internet, people are trying to understand why they loved the late, great Norm Macdonald so much. There are a lot of lovely reminiscences and great analyses, but if you just want to kind of roll around in Norm, I recommend reading his 2016 memoir Based on a True Story: Not a Memoir. This is a book that people (Norm fans? OK, just my husband) urged on me in 2016, and I didn’t read it then because I saw a review of it in the New York Times that was less than a hundred percent glowing.

In that review, John Williams, who did admit to laughing at some parts of the book, called what it did “evasive clowning,” complained that some parts are just recycled bits, and somewhat snarkily pointed out that it’s limited to talking about stand-up and Macdonald’s tenure on Saturday Night Live, because of the limits of Macdonald’s career: “Mr. Macdonald’s one big starring film vehicle, Dirty Work (1998), was called ‘leaden, taste-deprived attempted comedy’ in the New York Times. Other roles have included an uncredited bartender in Deuce Bigalow: Male Gigolo.”

I think Williams missed the point in that last bit, which is that the book is by an author deeply aware of what an awkward fit he made with the world of Hollywood celebrity—an author who made that awkward fit into kind of the point. In this “memoir,” the character of Norm is constantly wearing an SNL jacket, a Norm Show T-shirt, and a Dirty Work hat: a walking embodiment of insecure, grasping celebrity, and the opposite of whatever Norm—who famously lived in Los Angeles but didn’t drive, and so attended very few industry functions—was in real life. “New York City was the site of my greatest success,” the narrator writes. “I made it there and then I didn’t make it anywhere else. I guess Frank Sinatra isn’t so smart after all.”

Now that Macdonald is dead, reading the book—digesting its deep oddness—feels like communing with pure Norm. It’s got a gimmick: There’s a character in it, Keane, who’s the ghostwriter of the book, who constantly interjects to voice his annoyance with Norm, his fury at Norm, his total lack of respect for Norm. My colleague Lili Loofbourow, who reviewed the book for the Week when it came out, called Macdonald an “extraordinary wordsmith” and generally recommended the experience of reading Based on a True Story but found this way of constructing the story frustrating: “There has never been a less straightforward book. It’s playful and spry and just unbelievably cagey.”*

Lili is correct, and I get her frustration, but this is part of why I liked reading the book as a memorial exercise. I am but a medium-level Macdonald fan—a low-level one, according to my husband—and so I loved the parts of the book that other people might have found recycled, while also getting to be delighted to discover how freaking weird Macdonald could be when set loose on a long-form project. There’s a list of the “25 best Weekend Update jokes of all time,” the first of which came from Chevy Chase, the other 24 of which are Norm’s. (“Well, the results are in, and once again Microsoft CEO Bill Gates is the richest man in America,” goes No. 9. “Gates says he is grateful for his huge financial success, but it still makes him sad when he looks around and sees other people with any money whatsoever.”) The book also has the full text of the famous “Moth” joke, which has been much-shared on Twitter since Macdonald’s death was announced. In that clip from Conan O’Brien’s show, Macdonald puts the joke in the mouth of a driver; in the book, it’s a doctor who tells it, to a hallway full of people, and to raucous laughter, which “Norm” resents. “Everybody thinks they’re a comedian,” he gripes. “Especially in my line of work.”

As some have pointed out since Macdonald’s death, he had a history of building jokes around transphobic premises—a history he apologized for in a 2018 New York magazine interview with David Marchese. After talking around the issue, building jokes around it, Macdonald eventually said, “God bless trans people. They should be given every right in the world, and anybody who wants to hurt them is bad.” This part of Macdonald’s legacy is in the book, too. There is a chapter that’s basically a long prison rape joke. (I loved this book; I really hated that chapter.) There’s another plot line that revolves around “Norm’s” friend being in love with a woman who “Norm” knows “is a man.” This trans woman eventually betrays the friend for money.

But is it Norm Macdonald who’s responsible for these less-than-great parts of the book? Or is it “Norm,” the venal sybarite the ghostwriter Keane has created? In one of the ghostwriter’s narrated passages, Keane describes meeting “Norm” for the first time, at which occasion Keane uses the word “splendidly.” “It sounds womanish,” “Norm” says. “I don’t care what filthy things a man does with another man when they lay down together, but I just don’t want any words like ‘splendidly’ showing up in this book. You understand me, brother?” So was it the “real Norm” who has these thoughts and feelings? Or was the real Norm, off to one side, shunting these thoughts and feelings into a fictional “Norm”? Or was the real Norm just playing around? As Lili wrote for Slate on Thursday, this pile of obfuscation is confusing; this is perhaps, the point: “The book produced the perfect opposite of whatever illusion of intimacy a memoir is supposed to confer.”

But at the time of Macdonald’s death, it’s his material on cancer, like a chapter in the book where “Norm” takes a Make-a-Wish child to Canada to club a harp seal, that really makes the read worthwhile. He had cancer when he published the book, although that wasn’t known even to much of his friends and family until after his death. “The boy had been alive nine years, which made him young, but he would only be alive for one more year, which made him old,” “Norm” (or, actually, Keane) describes this child, a bitter and blunt way to talk about a dying kid.

“When it’s unexpected,” “Norm”/Keane writes, “death comes fast like a ravenous wolf and tears open your throat with a merciful fury. But when it’s expected, it comes slow and patient like a snake, and the doctor tells you how far away it is and when, exactly, it will be at your door. And when it will be at the foot of your bed. And when it will be on your flesh. It’s all right there on their clipboards.” This, of course, is not really funny. But it’s good.

Correction, Sept. 16, 2021: This article originally misspelled Lili Loofbourow’s last name.