Woodstock, the three-day music & art extravaganza first held in August 1969, wholeheartedly embraced love, unity and harmony within its festivities. The outdoor jamboree, which was attended by at least 400,000 people, showcased how music can be a form of peaceful protest and later became a defining symbol of the counterculture generation.

Thirty years later, Woodstock was revived by its original founders — Michael Lang, Artie Kornfeld, Joel Rosenman, and John P. Roberts — who attempted to bring a similar experience to a new group of youth. But despite the high hopes, Woodstock '99 was tarnished by poor venue facilities, riots, vandalism, assault, destruction and corporate greed, making it one of the most infamous festivals in music history.

Netflix's latest documentary, "Trainwreck: Woodstock '99," explores what went wrong in the making and execution of the 1999 shindig. Over the course of three episodes, the series highlights everyone from the festival's attendees and performers to its organizers, producers and business partners.

Here are 7 shocking revelations from the series:

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)Several members of the festival's production team, including Colin Speir, Lee Rosenblatt and Pilar Law, noted that the price hikes were prompted by the Woodstock founders and organizers. The higher-ups were hellbent on making a considerable profit, especially after their previous revival, Woodstock '94, tanked financially due to overcrowding and security issues.

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)The outhouse facilities were also a mess, with human waste pooling over the toilet seats and covering the surrounding floors. Many attendees recalled the horrid, overbearing smell and said they had to step in urine and feces while using the bathrooms.

"Like all departments, the Sanitation Department had budget cuts," Rosenblatt explained. "Trash services and the sewage services were all farmed out. So we're relying on all these subcontractors . . . And unfortunately, they did not do their jobs."

"One person said to me, 'I paid $150 to be here. You should clean it up,'" she recounted. "And I said, 'Well, this is a different kind of Woodstock.'"

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)

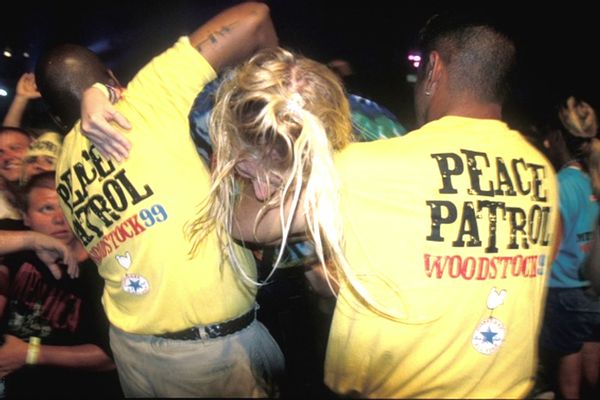

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)Crowds of men groping and sexually harassing young women took place without repercussions, mainly because the security at Woodstock '99 was both insufficient and inexperienced. There was not enough security available to closely monitor a crowd of 250,000 people, which encouraged mass crime to occur uncontrolled.

"Security at Woodstock '99 was kind of a joke," said Tim Healy, a former presenter at MTV. "It was like, you know, kids with yellow T-shirts."

In the documentary, Lang explains his reason for not hiring law enforcement, stating, "We didn't want anybody uniformed or anybody carrying a gun. We didn't want the influences of the government or of the police state or whatever. So the security that we hired, they were not armed. They were peace patrol."

One of those peace patrols was Cody, who was 18 years of age at the time. He signed up to work at Woodstock '99 because the hiring process was quick and simple — all he had to do was sign a form — and the $500 pay was quite generous too.

Despite the official title, there was nothing "peaceful" about the peace patrol. Many of the patrols engaged in reckless behaviors themselves, whether it was doing drugs while on the clock or selling yellow security shirts to random festivalgoers for some extra cash. For one unnamed patroller, Woodstock '99 was simply a place for "money and sex and b*tches . . ."

"It was laughable, you know? Like, 'Look at this. What a joke this is,'" Cody continued. "We could see how this is gonna go."

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)"The crowd was undulating. They were almost one organism," said David Blaustein, a former news correspondent for ABC News. On a similar note, Kyle, who worked stage security at the festival, likened the effect Limp Bizkit had on their crowd to a "hand grenade." That metaphorical "grenade" finally exploded when the band performed their 1999 hit single "Break Stuff."

Who is to blame for what happened afterward is still up for debate. But many Woodstock '99 organizers, including John Scher, pointed fingers at the band's lead vocalist, Fred Durst, for encouraging his crowd to go out of control.

During the opening of his performance, Durst asked his fans, "How many of you people here ever woke up one morning and just decided it wasn't one of those days, and you're gonna break some s**t?"

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)By day three, festivalgoers were exhausted, frustrated and agitated. To make matters worse, the festival's showering stations were sparse, thus prompting a few individuals to recklessly smash the water pipes.

Because the shower facilities were also near the bathrooms, the clean supply of water mixed in with runoff from the nearby porta-potties to create a nasty slush that looked like a mud slide. So unbeknownst to few boisterous festivalgoers, the "mud" they were fooling around in was actually feces.

Alongside the showers, the onsite drinking faucets were either broken or running murky, brown water. Joe Paterson, a public health investigator, examined samples of the drinking water available at Woodstock '99 and found that they were all severely contaminated with feces.

"The thought that people are out there, drinking this, exposing themselves, bathing in this stuff . . . It was like the worst nightmare," Paterson said.

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)Despite the inhumane conditions and complaints from festivalgoers, Woodstock '99 organizers continued to lie to members of the press, confidently telling them that everything was fine.

"We're happy. All is well," said Scher in a press conference that took place after festivalgoers violently tore down an elaborate wall of artwork displayed at the venue. "We haven't had any tough incidents."

When asked about the art wall, Lang told reporters, "I think the exterior wall just makes an amazing souvenir, and people just couldn't resist it. They were breaking it up into small pieces, I guess, just to have a piece of Woodstock."

Even the former mayor of Rome, New York, Joe Griffo, praised the event, saying, "I think it's been a memorable, exciting concert for all those involved and all those who covered it, and the community as a whole."

"I saw what was going on. I had spoken to enough people. I knew that they were full of shit," Blaustein said of the Woodstock organizers.

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)

Trainwreck: Woodstock '99 (Netflix)The final act at Woodstock '99 was the Red Hot Chili Peppers. During the band's closing set, the festival organizers handed out 100,000 candles to the crowd for a staged vigil mourning the victims of the Columbine school shooting, which took place a few months prior. The demonstration was meant to spotlight a new generation of youth taking a stance against gun violence.

As expected, the showcase backfired and instead, fueled festivalgoers, who were now fed up with their mistreatment, to start a riot. The candles were used to set a few fires in the crowd. Scraps of trash, stray pieces of wood and broken artwork were then thrown in, causing the fires to grow in intensity.

The crazed festivalgoers also targeted the venue's speaker tower, shaking it violently until it fell to the ground. They lit nearby trailers and trucks on fire. And afterwards, they attacked the cluster of food vendors by knocking down their tents and smashing their ATM machines, which contained around $60,000 to $70,000 in cash.

"To give flames to an audience that is three days into being treated like animals . . . It was not a very smart decision," said Rosenblatt, who warned Scher and Lang to not give out the candles but was ultimately told to shut up.

Years after the havoc, Scher and Lang are still standing by their actions. The organizers refuse to acknowledge any of their own wrongdoings, including the inadequate planning in preparation for Woodstock '99 and severe budget cuts, and blame the festivalgoers for what went down.

"They're the lunatic fringe. That segment of the population was both entitled and fearful of growing up, of having a real job and, you know, have a family and stuff like that," Scher said. "And they had lots of angst. Lots and lots of angst."

When asked what he thought went wrong with Woodstock '99, Rosenblatt shared a different and more apt reason:

"I can say it in one word: greed."

"Trainwreck: Woodstock '99" is streaming on Netflix. Watch a trailer for the series, via YouTube:

Read more

Netflix documentary lists:

Shares