The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE)

The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia: (10,000-323 BCE)

Contents

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Origin of the Phrygians Origin of the Phrygians

-

History of Phrygia History of Phrygia

-

Phrygian Language and Texts Phrygian Language and Texts

-

Phrygian Architecture and Art Phrygian Architecture and Art

-

Phrygian Cult Phrygian Cult

-

Summary Summary

-

References References

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

25 Phrygian and the Phrygians

Lynn E. Roller is Professor of Art History at the University of California, Davis.

-

Published:21 November 2012

Cite

Abstract

This article provides specific details on the alphabetic script and language of the Phrygians, who appeared in Anatolia during the Early Iron Age, ca. 1200–1000 BCE and retained a distinctive identity there until the end of Classical antiquity. Phrygian settlements can be recognized by the presence of texts in the Phrygian language, architecture and visual arts, and characteristic installations of Phrygian cult practice. The geographical extent of Phrygian territory covers a broad area, including Daskyleion near the Sea of Marmara in northwestern Anatolia, Gordion and Ankara in central Anatolia, and Boğazköy and Kerkenes Dağ east of the Halys River. Taken together, the linguistic and material evidence suggests that Phrygian culture was an influential element in the ethnic mix of populations on the Anatolian plateau.

The Phrygians appeared in Anatolia during the Early Iron Age, ca. 1200–1000 b.c.e., and retained a distinctive identity there until the end of Classical antiquity. Phrygian settlements can be recognized by the presence of texts in the Phrygian language, architecture and visual arts, and characteristic installations of Phrygian cult practice. The geographical extent of Phrygian territory covers a broad area, including Daskyleion near the Sea of Marmara in northwestern Anatolia, Gordion and Ankara in central Anatolia, and Boğazköy and Kerkenes Dağ east of the Halys River. Taken together, the linguistic and material evidence suggests that Phrygian culture was an influential element in the ethnic mix of populations on the Anatolian plateau.

Origin of the Phrygians

Evidence for the origin of the Phrygians is furnished by Greek literary sources, linguistic analysis, and material culture. Herodotus 7.73 reports that the Phrygians were originally at home in Macedonia, where they were called Briges, and that they changed their name to Phrygians when they migrated into Anatolia. The comment on the name change seems contrived, because the words “Briges” and “Phryges” are essentially the same, but Herodotus’s report, corroborated by Xanthos of Lydia (quoted by Strabo 12.8.3, 14.5.29), that the origin of the Phrygian people lay in southeastern Europe, is probably correct. This is demonstrated in part by linguistic evidence. The Phrygian language is a branch of the Indo-European language family that is closely related to Greek and Thracian (Strabo 7.3.2; Neumann 1988). It is notably different from Luwian and Hittite, the principal Bronze Age Anatolian languages, suggesting that the Phrygian language was intrusive into Anatolia, introduced through immigration from northern Greece or the Balkans. There is less consistency in the ancient literary sources on the date of the migration. The Iliad describes the Phrygians as allies of the Trojans during the Trojan War (Homer, Iliad 2.862, 3.184–88, 16.717–19, 24.545), which would suggest that the Phrygians were established in their Anatolian territory during the Late Bronze Age. Xanthos of Lydia (quoted by Strabo 14.5.29), however, stated that the Phrygian migration into Anatolia took place after the fall of Troy, or, in historical terms, after the end of the Bronze Age. The evidence from material culture at Gordion (see Voigt, chapter 50 in this volume), the only Phrygian site investigated to date with a continuous sequence of habitation levels from the Bronze through Iron Ages, supports both a post-Bronze Age date and the hypothesis of a Balkan homeland. The Gordion Late Bronze Age strata have yielded pottery with close affinities to Late Bronze Age wares of other central Anatolian sites; these are followed by strata containing pottery that is distinctively different in fabric, shape, and decoration, exhibiting parallels with handmade ceramics from Thracian sites in the Balkans (Henrickson 1994:106–8; Sams 1988, 1994:19–22, 126). The combination of linguistic evidence and ceramic parallels strongly suggests an infiltration of population groups from the Balkans during the early first millennium b.c.e.

The nature of the cultural shift occasioned by the arrival of the Phrygians is difficult to assess. At Gordion, significant changes in ceramics and architectural features found in early Iron Age levels appear to signal the arrival of a new people, but there is no evidence for a violent transition between the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age (Voigt 1994:276–78); instead, the material suggests that there may have been several successive waves of new settlers and that the transition lasted over a century or more. The limitation of the evidence to a small area within one single site, Gordion, makes these conclusions tentative (see Voigt, chapter 50 in this volume).

History of Phrygia

The history of the Phrygian people following their establishment in Anatolia is drawn from the material evidence of Phrygian settlements and cult centers coupled with the written documentation of the Phrygians’ neighbors, the Assyrians to the east (see Radner, chapter 33 in this volume) and the Greeks to the west (see Harl, chapter 34, and Greaves, chapter 21 in this volume). Written texts in the Phrygian language offer some supplemental information, but no list of Phrygian kings or annalistic tradition that recorded Phrygian history is known. Even the name of the people is uncertain: the word Phrygian is Greek and is not attested in any extant Phrygian text.

The earliest evidence for the formation of a complex state in Phrygia comes from Gordion. Iron Age levels at Gordion reveal an abrupt change from simple houses constructed on a frame of wooden posts to substantial stone buildings with carefully worked masonry. Some of the early stone buildings are in the form of a megaron, a two-room rectangular structure with an entrance on the building’s short end. This building type is characteristic of the élite quarter in a Phrygian city, extensively attested in subsequent levels at Gordion and also at Kerkenes Dağ. This shift in architecture suggests the instigation of large communal projects involving extensive labor, and its appearance at Gordion signals the emergence of a centralized state where resources are controlled by one individual or a small group of élite individuals. The date of this transition at Gordion should probably be placed in the early ninth century b.c.e. (Voigt and Henrickson 2000; Voigt 2005:28–31). Within a generation or two, an extensive élite quarter in Gordion was constructed, with a monumental gateway, a large central courtyard flanked by several buildings in the megaron plan, and an inner courtyard with additional megara that may have been residences for the ruling class élite. In addition, centralized economic control is implied by multiroom complexes nearby that were devoted to intensive processing of foodstuffs and textiles, probably carried out by servile labor. A destructive fire at the end of the ninth century b.c.e. caused extensive damage to this level of the early Phrygian city, but the fire, probably of accidental origin, did not constitute a major setback in the community, as the élite quarter was soon rebuilt in an even more elaborate architectural complex (Voigt 2007, and see Voigt, chapter 50 in this volume). A major Phrygian center at Daskyleion, near the Sea of Marmara, with evidence of monumental construction, dating from the eighth century b.c.e., offers testimonia that a complex Phrygian community also existed in western Anatolia (Bakır 1995:271–73).

Along with the appearance of monumental architecture are the earliest examples of burial tumuli with rich grave goods, surely burial places of the élite (see Sams, chapter 27, and Voigt, chapter 50 in this volume). Tumulus burials at Gordion first appear during the ninth century b.c.e., and this process accelerates in the eighth century b.c.e. with the construction of larger and more elaborately furnished burial tumuli (Young 1981). Several burial tumuli in the region surrounding Ankara demonstrate that this custom was well established among the Phrygian élite (Caner 1983:13–15; Tuna 2007). The tumuli are noteworthy not only for their size but also for their contents; they contained a rich assortment of fine pottery, bronze vessels, bronze fibulae (ornate dress pins), textiles, decorated bronze-leather belts, and intricate wooden furniture, attesting to a high level of craftsmanship and the wealth of the élite. All tumuli appear to contain the burial of a single individual. Where identifiable, the majority proved to be burials of adult males, but there was at least one burial of a child in Gordion (Tumulus P, Young 1981:9) and one of an adult woman in Ankara (Tumulus II, Caner 1983:15). The construction of the tumulus series continued until the mid-sixth century b.c.e. Taken together, the existence of urban centers with complex plans, monumental architecture, and high quality luxury goods demonstrates the presence of a prosperous and powerful Phrygian society.

It is uncertain whether all Phrygian settlements were part of a single political state, but it seems probable that much of central Anatolia was controlled by a Phrygian monarchy centered at Gordion. Most rulers of this Phrygian kingdom are anonymous, but the name Midas, preserved in Phrygian, Assyrian, Greek, and Latin sources, recurs regularly, suggesting that this individual was an important ruler with a strong international presence. Although Midas could have been a dynastic name borne by several individuals, Classical and Assyrian sources combine to give a vivid picture of one man whose period of rule was ca. 733–677 b.c.e. (Berndt-Ersöz 2008). References to Midas in Greek and Latin texts are often infused with folk tale and legend (Roller 1983), and the occurrences of the name Midas in Phrygian texts, especially the main inscription on the cult monument at Midas City and a stone stele from Tyana (Brixhe and Lejeune 1984:M-01a, T-02) are difficult to date securely. However, an individual named Mita (presumed to be the same as the Phrygian and Greek Midas) is mentioned several times in Assyrian documents from the reign of Sargon II (r. 721–705 b.c.e.), where he is identified as the ruler of the Muški (Berndt-Ersöz 2008:17–21). These documents record the activities of a powerful military figure who was a rival of the Assyrians, first allying himself with several independent Anatolian states, including Que, Tyana, Karkamiš, and Tabal, before being defeated by the Assyrians and becoming their ally (Berndt-Ersöz 2008:34–36; Mellink 1979; Vassileva 2008; see Sams, chapter 27 in this volume).

The Muški are probably to be identified as an Anatolian group in eastern Anatolia under Phrygian political control; thus, Midas was the ruler of both the Phrygians in central Anatolia and the Muški in eastern Anatolia (Mellink 1965, 1991:622–23; Wittke 2004). Assyrian sources make it clear that Midas ruled a powerful kingdom with the resources to rival the contemporary society of Assyria and that a strong Phrygian presence in central and eastern Anatolia continued well into the seventh century b.c.e. The international contacts of the Phrygians are further confirmed by the presence of valuable objects from southeastern Anatolia, north Syria, and Cyprus found in ninth- and eighth-century b.c.e. contexts at Gordion (Young 1962:167–68, 1981:31, 36) and by Phrygian goods at Samos and Delphi (Ebbinghaus 2008; Herodotus 1.14). A marriage alliance between Midas and the daughter of a prominent Greek chieftain from Kyme, a Greek city in northwestern Anatolia (Aristotle frag. 611.37; Pollux, Onom. 9.83) offers additional evidence for the international connections of Phrygian rulers. The presence of valuable Phrygian objects, several bearing Phrygian inscriptions, in the burial tumulus of a woman in Lycia, may also be the result of an external marriage alliance (Börker-Klähn 2003; Varinlioğlu 1992).

After the reign of Midas, much less is known about the political status of the Phrygians. During the mid-seventh century b.c.e. the Cimmerians, a nomadic people from the region north of the Black Sea, invaded Anatolia and caused a great deal of damage, including the destruction of Sardis, capital of the Lydian kingdom (Herodotus 1.6, 1.15; Strabo 13.4.8, 14.1.40; Parker 1995; see Sams, chapter 27 in this volume), but their impact on Phrygia is less certain. Strabo 1.3.21 records that a Phrygian king Midas died as a result of a Cimmerian raid; this is likely to be a later Midas, who ruled in the 640s b.c.e., and Greek sources conflated him with the earlier and better known ruler (Berndt-Ersöz 2008:36). However, the series of rich tumulus burials at Gordion continued unbroken through the seventh century b.c.e., and there is little evidence in the Gordion settlement for disruption by the Cimmerians. A more significant change occurred in the late seventh or early sixth century b.c.e., when western Phrygia came under the control of the Lydian kingdom. Herodotus 1.28 records that the Phrygians were subdued by the Lydian king Croesus (ca. 560–546 b.c.e.), although it is likely that much of Phrygia was under Lydian control during the reign of the previous king, Alyattes (ca. 610–560 b.c.e.). Substantial finds of Lydian pottery in Gordion from the later seventh and early sixth century b.c.e., much of it found near the mudbrick fortifications beyond the Gordion citadel mound, offer evidence for an increasing Lydian presence there.

During the later seventh century b.c.e. a new settlement with a strong Phrygian element was established at Kerkenes Dağ, east of the Halys River. This mountain-top site, fortified by a seven-kilometer circuit of walls, provided a strong military presence near a major transportation route extending through central Anatolia. Finds of Phrygian inscriptions, architecture in the Phrygian megaron form, and Phrygian sculpture confirm that the Phrygians formed a key element of the population (Draycott and Summers 2008). The lack of Lydian material suggests that the settlement was not under the control of the Lydian kingdom west of the Halys River. Kerkenes Dağ may be ancient Pteria, an independent city that survived until the 540s b.c.e. when it was captured and demolished by Croesus during his campaigns against the Persian king Cyrus (Herodotus 1.76; Summers 2006; Summers and Summers 2008).

A pivotal event in the history of the Phrygians was the conquest of Anatolia by the Achaemenid Persians. The sack of Sardis by the Persians in the 540s b.c.e. brought the extensive territory of the Lydian kingdom, including Phrygia, under Achaemenian control. This event is reflected in the destruction of the fortress city at Kerkenes Dağ, and is also attested at Gordion, where the mudbrick fortifications were destroyed by military force (see Sams, chapter 27 in this volume). In addition, the occupation levels at Gordion reveal a significant displacement and rebuilding during the later sixth century b.c.e. (Voigt and Young 1999), and the practice of tumulus construction in Gordion ceases, a circumstance that may be connected with the suppression of the élite class in Phrygia (DeVries 2005:53). The Persians divided Phrygia into two administrative units, or satrapies. One, Hellespontine Phrygia, encompassed northwestern Phrygia, with its capital at Daskyleion near the Black Sea. The other, Greater Phrygia, comprised the southern part of Phrygia; its center was at Kelainai (modern Dinar).

The official Persian presence in Hellespontine Phrygia is well demonstrated at Daskyleion. Here a smaller version of the Persian court was constructed, including a residential palace for the satrap, a hunting park, or paradeisos, for which the Persians were well known (see Xenophon, Hellenica 4.1.15), and a cult sanctuary with a Persian fire altar (Bakır 1995, 1997, 2004, 2006). Fine architecture and sculpture attest that the resources of the Achaemenid satrap made this a prosperous and beautiful city. The population of the city, however, was very mixed; Phrygians continued to be a prominent element, judging from the frequency of inscriptions in the Phrygian language, and there is also evidence for Greek speakers, Lydians, and a Jewish community. The presence of much Greek pottery and Greek workmanship in local sculpture suggests extensive contact with neighboring Greek populations.

Central Phrygia, in contrast, seems to have undergone a period of economic decline, as power and resources were concentrated in the west. At Gordion, much of the fine stone architecture of the eighth-century b.c.e. city had been removed for use in other building projects by the early fourth century b.c.e. (Voigt and Young 1999:236). The city that Alexander found during his visit in 333 b.c.e. was an important regional commercial center but had long since lost its status as an impressive political capital.

Phrygian Language and Texts

The Phrygian language, attested in a variety of written texts, is notable both for its geographical breadth and its longevity. The corpus of Phrygian texts has been collected and classified by region (Brixhe 2002b, 2004; Brixhe and Lejeune 1984; Brixhe and Summers 2006). These are found throughout the full extent of Phrygian settlements, from Bithynia and the site of Daskyleion near the Sea of Marmara in western Anatolia, to the territory east of the Halys River at the sites of Boğazköy, Kerkenes Dağ, and Alaca Höyük. Additional Phrygian texts outside this range are also known, with examples from Tyana (Brixhe and Lejeune 1984:T-01, 02, 03), Lycia (Varinlioğlu 1992), Delphi (Jeffery 1990:39), and Persepolis (Brixhe 2004:118–36). These are likely to be the result of diplomatic treaties, gift exchanges, or personal notations by Phrygians traveling or living abroad.

Phrygian texts fall into two broad chronological groups. The earlier, known as Palaeo-Phrygian, uses an alphabetic script consisting of twenty-six letters; nineteen letters are identical with proto-Greek forms and seven are unique to Phrygian (Brixhe 2007). It is uncertain whether the Phrygians adopted the alphabet from the Greeks, or whether Greek and Phrygian scripts were derived from a common source and developed along parallel lines. The earliest Palaeo-Phrygian inscriptions, found in Tumulus MM at Gordion, are dated to ca. 740 b.c.e.; these consist of proper names incised onto objects found in the tomb (Brixhe, in Young 1981:273–77) and onto the wooden beams used to build the tomb chamber (Liebhart and Brixhe 2009). Palaeo-Phrygian texts continued until the late fourth century b.c.e., when both language and script were superseded by Greek. The latest known Palaeo-Phrygian inscription, a funerary epitaph of the late fourth or early third century b.c.e. from Dokimeion (Brixhe 2004:7–26), is written in the Phrygian language, but uses the Greek alphabet. Additionally, there is a series of Phrygian inscriptions from the later first through third centuries c.e. known as Neo-Phrygian texts; these use the Phrygian language written in the Greek alphabet.

The subject matter of Palaeo-Phrygian texts is quite varied, and includes religious texts, political documents, and funerary epitaphs on stone, as well as a large number of graffiti on pottery, wood, and metal wares. The most common subject matter of Phrygian stone inscriptions concerns religious texts, including cult dedications and apotropaic formulae. Votive dedications are found on several of the largest cult façades in the Phrygian highlands (Brixhe and Lejeune 1984:M-01a, W-01; Haspels 1971:289–94), and also on monuments from Gordion and Kerkenes Dağ (Brixhe and Lejeune 1984:G-02; Brixhe and Summers 2006:106). Texts that record political documents are less frequent, although three examples found in Tyana in southeastern Anatolia (Brixhe and Lejeune 1984:T-01, 02, 03) may reflect Phrygian diplomatic activities with another Anatolian state in this area. One of these (Brixhe and Lejeune 1984:T-02b) includes the name Midas; this may refer to the late eighth–early seventh century b.c.e. Phrygian ruler already discussed, known from Assyrian sources to have been active in this region.

As already noted, the Phrygian language was part of the Indo-European language family, of the same branch as Greek and Thracian. In a number of key grammar points, such as the case structure of nouns and basic verb forms, Phrygian syntax shows close affinities with Greek. Thus, in many dedicatory texts the name of the dedicator, the object of the dedication, and the verb can be read. There are comparatively few lexical overlaps between Phrygian and Greek, however, and this circumstance means that the language has not been fully deciphered. Most Phrygian texts are very short; many of the pottery graffiti, for example, consist of a single name or just a few letters of a name. Stone inscriptions are sometimes longer, but even these often consist only of a few lines. The longest extant Palaeo-Phrygian text, the late fourth-century b.c.e. epitaph, contains 265 characters, and the second longest, a dedication to Matar Kybeleia found in Bithynia (Brixhe and Lejeune 1984:B-01), contains only 230 characters. All of these factors contribute to the difficulty of interpreting the language.

The inscription above the main cult façade at Midas City (Brixhe and Lejeune 1984:M-01a) helps illustrate the extent of our understanding of Phrygian. The inscription reads ates arkiaevais akenanogavos midai lavagtaei vanaktei edaes. (Here I follow the convention, used by Brixhe and Lejeune 1984, of transliterating the Phrygian script into the lowercase Latin alphabet.) The text can be translated “Ates (a proper name) arkiaevais (patronymic?) akenanogavos (title?) dedicated [this] to Midas leader of the people and ruler.” Thus we have the subject, Ates, the main verb edaes, “he dedicated,” which also occurs in other Phrygian texts, and the object of the dedication, Midas, written in the dative case. The dative Midai is followed by two nouns, also in the dative, that share a common form with Greek vocabulary; the first, lavagtaei, is a compound noun akin to Greek λαός plus ἡγέτης (leader of the people), and the second vanaktei, parallels the Greek ἄναξ (lord, ruler). This text demonstrates the close similarity of Phrygian to Greek in grammar, evident in the case endings of nouns and the use of the epsilon augment for the aorist verb, and the overlap in vocabulary. The Phrygian text shows particularly close affinities with the more archaic Greek of the epics, evident in Phrygian use of the digamma (here transliterated as v) in the words lavagtaei and vanaktei, and in the choice of vocabulary, since the words λαός and ἄναξ occur frequently in the Iliad and the Odyssey, where both use the Greek digamma, but are less common later.

Another example of a Palaeo-Phrygian text, this one from Gordion, offers a similar picture of the Phrygian language. Incised onto a broad flat stone, the text is intertwined around a representation of two footprints (Brixhe and Lejeune 1984:G-02). It reads as follows: (line 1) agartioi iktes akiokavoi; (line 2) iosoporokitis.; (line 3) kakoioitovo podaska[.]. Here again we can recognize the grammatical form and meaning of several words and gather the general sense of the inscription. The first line is likely to begin with a proper name in the dative case, perhaps the object of the dedication; the second line begins with the word ios, the relative pronoun equivalent to the Greek ὅς, “whoever”; and the third line contains the words kakoioi, probably an optative verb related to the Greek κακόω, “maltreat” or “ruin,” and podas, a form of the Greek noun πούς, ποδός, “foot”; this latter translation is reinforced by the picture of footprints on the stone. The inscription appears to be a combination of dedication and apotropaic text, which reads approximately: “[Dedication] Whoever sets foot on [this], may he be ruined/cursed.” These two examples also illustrate the gaps in our knowledge of the Phrygian language, because both use Phrygian words that do not exhibit close lexical similarities to Greek and remain unknown to us. The brevity of the texts and the formulaic quality of the subject matter also impede more precise understanding.

In addition to more formal inscriptions on stones, there are numerous examples of graffiti incised onto various media. Five bronze bowls from Tumulus MM in Gordion have proper names incised into wax that was added to the rim of the bowl, and eleven silver and bronze objects found in a tumulus in Bayandır bear proper names incised directly onto the metal. Personal names also appear on the wooden beams of Tumulus MM and on wooden furniture in Gordion. Several hundred examples of graffiti scratched on pottery have been found at Daskyleion, Dorylaion, and Gordion, many on ordinary coarse ware fabrics. Most of these are personal names, although some longer texts are known. Although these do not help our understanding of the Phrygian language, they demonstrate that writing was very widespread, suggesting a fairly high rate of literacy among the Phrygian population.

Palaeo-Phrygian texts disappear after the early third century b.c.e. After a gap of more than 300 years, texts written in the Phrygian language but using the Greek alphabet are once again found during the later first through third centuries c.e.; these are known as Neo-Phrygian. One hundred fourteen examples have been published (Brixhe 1993, 1999, 2002a:248). Of these, fifty are monolingual Phrygian texts, sixty-three contain texts in both Greek and Phrygian, and one is ambiguous (Brixhe 1993:292, 2002a:248). All Neo-Phrygian texts are funerary epitaphs, and all but seven consist solely of curses directed toward a potential grave robber. One example (Brixhe and Neumann 1985) preserves the longest known Phrygian text, but most of the other Neo-Phrygian texts are very short. Greek was clearly the more widely understood language in Roman Phrygia, since the Greek precedes the Phrygian text in nearly every example of the sixty-three double-language texts. The Greek-Phrygian epitaphs follow a very standard pattern: the Greek text gives the name or names of the dedicators, their relationship to the deceased and to each other, and often other information about the family, while the Phrygian text is used to express a curse directed at the potential violator of the tomb. A few of the monolingual Phrygian texts record the names and family affiliations of the dedicators in Phrygian, but most contain only the curse formula.

The reason for the renewed use of the Phrygian language during the Roman period is uncertain. One hypothesis posits that Phrygian continued to be spoken by the rural population in central Anatolia even after the written Palaeo-Phrygian language had died out, and the appearance of Neo-Phrygian texts results from increasing affluence in rural areas that enabled stone funerary monuments to be made by a population group that had previously been too poor to afford them (Brixhe 2002a:252–53; Mitchell 1993:I,174). It is also possible that written Phrygian was deliberately revived by a more educated Phrygian population who wished to stress their regional identity and their distance from the dominant Greco-Roman culture.

Phrygian Architecture and Art

Phrygian architecture and art have a distinctive character that contributed greatly to the visual style prevalent in western Anatolia and the Greek cities of Asia Minor. The most characteristic form in Phrygian architecture is the megaron, a long, narrow rectangular building with a single entrance in one short side that leads to two rooms, a smaller front room and a larger room behind it. Although the term megaron is borrowed from the architecture of Mycenaean Greece, the Phrygian megaron is a building type with roots in Anatolia that extend back to the third millennium b.c.e. The megaron can be a large structure with internal supports in the main room, attested by examples at Gordion and Kerkenes Dağ; these may have served as a residence or audience hall for the ruling élite. At Gordion, buildings in the megaron plan were also used for utilitarian purposes, such as food preparation and textile production (see Voigt, chapter 50 in this volume).

Phrygian visual arts are characterized by a strong interest in abstract geometric forms, and to a lesser extent in figured art, through representations of human and animal figures. Among the media in which Phrygian craftsmen excelled are pottery, bronze, and wood; objects in precious materials such as ivory and silver are also known. The interest in geometric patterning is apparent in fine pottery, where painted decoration includes a complex repertory of geometric forms (Sams 1994). It is also well attested in the intricate wooden furniture found in Phrygian burial tumuli, in which inlay work forming patterned designs predominates (Simpson 1988; Simpson and Spirydowicz 1999; Simpson 2010). Similar geometric patterns can be observed in a fine mosaic from Gordion (Young 1965:10–11) and were presumably used extensively in textiles (Boehmer 1973; Burke 2005). The complexity of the geometric designs offers evidence of a high level of craftsmanship and aesthetic sensibility, and in some cases may also contain cult symbolism (discussed further below).

Representational art first appears during the ninth century b.c.e. Early examples, such as a series of orthostat reliefs from Early Phrygian Gordion, show extensive influence from Neo-Hittite sculptural relief in both style and subject matter (Sams 1989), but a distinctively Phrygian style soon began to emerge. The lion was a popular subject; lions are found as architectural sculpture in Early Phrygian Gordion (Sams 1989:figs. 1–2; Young 1956:figs. 42–43) and in funerary sculpture in the Phrygian highlands, in reliefs at Arslantaş (figure 25.1) and Yılantaş (Haspels 1971:figs. 131, 141). Comparatively few examples of the human form are known, and these are usually cult objects. The most frequent is the representation of the Phrygian mother goddess (discussed further below); she is shown as a mature female, heavily draped in an elaborate long gown, high headdress, and veil. A series of small youthful male figures, known from Gordion and Boğazköy, probably represents attendants on the mother goddess, since they carry an attribute appropriate to her cult. A sculpture depicting a life-size male figure wearing a long gown, found near the entrance to the palatial complex at Kerkenes Dağ, is also likely to have been part of a cult installation (Draycott and Summers 2008). No examples of sculpture that depicts a narrative, whether legendary or historical, are known. The lack of extensive sculptural monuments may be the result of the dearth of high-quality stone for carving, although the situation may also reflect an ideological choice not to advertise the traditions of the Phrygians through formal public sculpture.

Arslantaş, Phrygian grave with relief of lions (photo by author).

The Phrygians also excelled in metal wares, especially bronzes, used for a variety of fine vessels, belts, and fibulae (Ebbinghaus 2008; Young 1981). These exhibit craftsmanship of a very high order and, in the case of fibulae and belts, confirm Phrygian interest in elaborate costume. Some of the bronze motifs, such as animal-headed situlae and cauldron attachments, find parallels in the art of southeastern Anatolia and Assyria. Precious materials were also used; an ivory figurine was found at Gordion (Young 1966:pl. 74), and silver vessels and ivory and silver figurines were recovered from the burial of a Phrygian woman in Lycia (Börker-Klähn 2003:77–84).

During the later sixth and fifth centuries b.c.e. Greek influence becomes a prominent feature of the visual arts in Phrygia. Relief sculptures attached to a Phrygian chamber tomb at Yılantaş include reliefs of hoplite warriors and a Gorgoneion (Haspels 1971:figs. 154–56), both similar to sixth century Greek forms. Similarly, frescoes from a building in Gordion (Mellink 1980) and painted panels from a tomb in Tatarlı (Summerer 2007a, 2007b) display figures drawn in Greek style, although the subject matter and costumes of the figures reflect the traditions of western Asia. These examples indicate that Greek visual style was increasingly integrated into the visual arts of Phrygia during the sixth through fourth centuries b.c.e. This process accelerated toward the end of the fourth century b.c.e. with the conquest of Phrygia by the Macedonians.

Phrygian Cult

Cult practice was a distinctive feature of Phrygian society, one with a continuing legacy in Greek and Roman cult. Yet many features of Phrygian cult practice remain unclear. A few texts in the Phrygian language (largely undeciphered) are found on cult monuments, but most information comes from the physical remains of cult, including images of human and animal cult figures, carved façades, stepped monuments, and idols. Some Phrygian cult places are found in urban settings, whereas others are located in isolated places and may have been centers of pilgrimage. Chronology remains a problem; many cult objects were found reused in later contexts, and monuments that are still standing in the open are often quite worn, making a determination of date difficult. It is likely, though, that most of the major cult monuments were made during the main flourishing period of Phrygian culture, the ninth through early sixth centuries b.c.e.

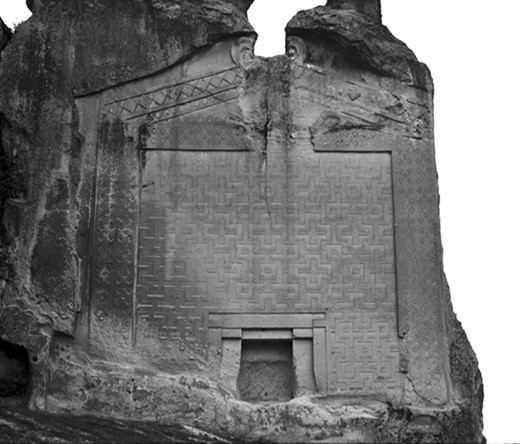

The Phrygian pantheon probably included a number of deities, both male and female, but only one was consistently represented in anthropomorphic form. This is a female divinity addressed as Matar, meaning “Mother” (Roller 1999:64–115; see Voigt, chapter 50 in this volume). The word Matar appears in several Phrygian inscriptions, often with an epithet. One epithet, Kybeleia, or “mountain” in the Phrygian language, forms the source of the goddess’s Greek name, Cybele. The Phrygian goddess Matar was represented as a mature standing female who wears a long gown and an elaborate high headdress and veil. Most images of the deity are reliefs carved onto stone orthostat blocks or onto rock outcrops that occur in the natural environment. These cult reliefs are widely distributed, with examples known from Boğazköy, Ankara, Gordion, and many in the Phrygian highlands region (Haspels 1971:73–111). The deity can be shown with several attributes, including a drinking cup or bowl, a small round object, perhaps a pomegranate, and a bird of prey. She can also have attendants; the Boğazköy goddess is accompanied by two smaller male figures who play musical instruments, the goddess on the Arslankaya relief in the Phrygian highlands is flanked by two huge lions (figure 25.2), and the deity on a relief from Ankara/Etlik is accompanied by a composite human-animal figure that raises its hands in a gesture of prayer and protection. The goddess is regularly depicted in an architectural frame resembling an open doorway placed in a rectangular building. There are also several reliefs that depict the architectural frame and central doorway niche but have no image of the deity. Among these is the main relief panel at Midas City, the largest Phrygian cult relief (figure 25.3). Here the central niche could have held a portable image of the deity, brought there on the occasion of special festivals. The reliefs often depict very specific details of the architectural frame, including the timbers that formed the frame of the “building” and a curved akroterion above the roof gable. These are surely features that existed on actual Phrygian buildings: the rectangular building with a central doorway recalls the Phrygian megaron, wooden beams were extensively used in Phrygian architecture, and actual examples of stone akroteria have been found at Gordion. On many of the reliefs, both those with and those lacking an image of the deity, the carved façade was decorated with a rich series of complex patterns that depict mazes built around a series of interlocking cross and square patterns. Examples include several of the most striking reliefs, such as the Midas City façade and the Arslankaya, Büyük Kapıkaya, and Maltaş monuments (Haspels 1971:figs. 8, 189, 183, 157).

Arslankaya, cult relief depicting goddess flanked by lions (photo by author).

Midas City, main façade with cult relief (photo by author).

The locations of the Matar reliefs offer an indication of the deity’s function. Most are found in spaces that marked boundaries controlled by a community. Reliefs are found near city gates (at Boğazköy and Gordion), along roads or other transportation routes (near Ankara and in the Phrygian highlands), and in areas that marked the entrance into a valley with rich tilled land (Arslankaya). Shrines are also found in connection with burial tumuli and chamber tombs (Ankara), implying that the Phrygians created sacred space to mark the boundary between the living and the dead.

The meaning of the architectural frame and geometric designs is uncertain. It is possible that the reliefs imitate the front wall of a temple dedicated to Matar, although to date no examples of temples or other cult buildings within an urban center in Phrygia are known. An alternative interpretation is that the “building” depicted in the Matar reliefs represents a royal residence, and the combination of deity and palatial façade functioned as an advertisement of close contacts between the Phrygian ruler and the deity. This is supported by the close correlation between the geometric patterns found on the façades and very similar patterns on the wooden serving stands from the burial tumuli in Gordion (Simpson 1998; Young 1981:fig. 33, 104). These serving stands, supports for bronze cauldrons that formed part of the banqueting equipment used in the funerals of the Phrygian ruling class, were inlaid with a series of maze patterns composed of interlocking crosses and squares, much like the decorative schema found on the carved façades. The use of the same geometric iconography for the funerary furnishings of Phrygian royalty and for the carved Matar façades is likely to be intentional, emphasizing the connection between goddess and ruler. By depicting this connection in a public context, the façades advertise the goddess Matar as a deity who protects the ruler and, by extension, the Phrygian state. The importance of the ruler in Phrygian cult is further suggested by the life-size statue of a standing male figure found near the main entrance to the city at Kerkenes Dağ. This figure appears to have been a cult monument, perhaps for a heroized ruler or ancestor whose presence protected the city (Draycott and Summers 2008:58–60).

Another common type of Phrygian cult installation is the stepped monument (Berndt-Ersöz 2006:40–49). These can be simply a series of steps, usually three to five, carved into living rock in an outdoor setting. On some monuments the steps are surmounted by a round disc, and in some cases the disc has the simple features of a human being, suggesting that it was a simple idol intended to represent an anthropomorphic deity. Like the Matar reliefs, the stepped monuments, both with and without idols, tend to be located near the walls and gates of settled communities (Midas City, Kerkenes Dağ), along roads or near entrances of valleys and plains with fertile land (many in the Phrygian highlands), or in areas near funerary monuments (Köhnüs valley in the Phrygian highlands). Other stepped monuments are located in remote areas, as if the Phrygians wanted to extend the divine presence beyond the boundaries of the settled community. An example is furnished by Dümrek, a site on a ridge above the Sangarios River about thirty kilometers northwest of Gordion, with roughly a dozen stepped monuments, including one with an idol. Individual idols are also known; a number of small idols were found in domestic contexts in Gordion. Other sacred places include stone hollows and basins, often located near stepped monuments; these may have been sites for offering deposits.

The stepped monuments and idols are rarely inscribed, so we do not know the identity of the deity or deities to whom they were dedicated, although the high frequency of stepped monuments and idols suggests that other deities in addition to the goddess Matar were widely worshiped. Greek sources indicate that the Phrygians worshiped a male deity whom they addressed as “Father,” perhaps the masculine counterpart of the mother goddess. In a few cases a group of two idols suggest that a pair of deities, perhaps the father and the mother, was worshiped together. Examples include a pair of idols on the citadel of Midas City and a relief with two idols near Ankara.

After Phrygia was absorbed into the Achaemenian Persian Empire, construction of new carved façades, reliefs, and stepped monuments became less common, although the older monuments continued in use as places of cult practice. During the Hellenistic period many objects connected with Phrygian cult, especially the images of Matar, become highly Hellenized, but the traditional deities, particularly the Phrygian mother goddess and a Phrygian male deity, often identified with Zeus, continued to be worshiped.

Summary

Although many lacunae remain in our understanding of Phrygian history, culture, and language, the surviving material gives a vivid picture of a dynamic and creative people, one with a profound impact on the history of Anatolia. The Phrygians’ migration into central Anatolia was undoubtedly propelled in part by the collapse of the dominant political structures in the eastern Aegean at the end of the Bronze Age. The power gap in Anatolia resulting from the collapse of the Hittite Empire enabled the Phrygians to establish themselves in northwestern and central Anatolia and become a prominent presence in the region. By the ninth century b.c.e. the Phrygians had gained enough political and economic stability to establish a complex state (or states), and by the eighth century b.c.e. they appear to have been the dominant political power in central Anatolia, with sufficient military and diplomatic strength to pose a challenge to the Assyrian Empire. By the end of the seventh century b.c.e. most Phrygian settlements had come under the control of the Lydians, but the Phrygians retained their language and many distinctive cultural features even after the loss of political independence. Phrygian material culture exhibits a high level of skill in many crafts, especially pottery, wood, and metal work. Particularly in the visual arts and in their religious practices, the Phrygians created a distinctive legacy, one with a lasting impact on their Anatolian neighbors and on Greek settlements in Asia Minor.

References

Primary Sources

Xanthos. Lydiaka. In

Secondary Sources

Bakır, Tomris.

Bakır, Tomris.

Börker-Klähn, Jutta.

Brixhe, Claude.

Brixhe, Claude.

Burke, Brendan.

DeVries, Keith.

Ebbinghaus, Susanne.

Henrickson, Robert C.

Mellink, Machteld J.

Mellink, Machteld J.

Mellink, Machteld J.

Sams, G. Kenneth.

Summerer, Latife.

Summerer, Latife.

Summers, Geoffrey D. and Françoise Summers. 2008. Kerkenes News 10 (2007). METU Press. www.kerkenes.metu.edu.tr.

Tuna, Numan.

Vassileva, Maya.

Voigt, Mary M.

Voigt, Mary M.

Voigt, Mary M.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 4 |

| November 2022 | 4 |

| December 2022 | 13 |

| January 2023 | 7 |

| February 2023 | 7 |

| March 2023 | 8 |

| April 2023 | 6 |

| May 2023 | 8 |

| June 2023 | 7 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 3 |

| September 2023 | 3 |

| October 2023 | 7 |

| November 2023 | 4 |

| December 2023 | 6 |

| January 2024 | 7 |

| February 2024 | 10 |

| March 2024 | 8 |

| April 2024 | 7 |