The Fijian Islands are celebrated as a lovely vacation paradise with a friendly population, and it is difficult to imagine that they were once known as the Cannibal Isles. In the 1700 and 1800’s, sea captains sailed far away from the Cannibal Isles for fear of being shipwrecked and therefore victims of the locals who actively practiced cannibalism.

My visit to two islands in Fiji in October 2017 allowed me to meet locals who were amongst the kindest and most hospitable I have met in my travels. Our taxi driver, a very kind young man from Lautoka, invited us to his home for tea and dessert. The next day in Suva we were treated as honored guests of the native Fijian congregation at the Centenary Methodist Church for Sunday services.* Today, the Christian faith of Fijians is strong and fervent, and Sundays are sacred, but their ancestors less than two hundred years ago certainly would not have greeted me in such a hospitable manner.

Congregants from Suva Methodist Church

After the lovely and spiritual three-hour church service, all in native Fijian, we went to the Fiji Museum in Suva. Their collections reveal the details of the widespread practice of cannibalism that gained the islands such a dark reputation among early explorers and missionaries. Today, the Fijians don’t hide their history but present it in a historical atmosphere filled with artifacts, stories, and photos. There is even a display to honor Reverend Thomas Baker, the last missionary killed and eaten in 1867.

History of Cannibalism in Fiji

Archeological evidence shows that cannibalism was practiced in Fiji for the last 2,300 years. By 1800, cannibalism was a normal and ritualized part of life, integral to Fijian religion and warfare.

Eating human flesh was not done out of a need for food to avoid starvation, but rather was an act of vengeance beyond the grave. Cannibalism was an act of ultimate insult in a society based upon ancestral worship. Those eaten were enemies conquered in war, but other conquered people, slaves, shipwrecked sailors, or those from a lower caste in their community were also victims.

The Fijians’ ancient religious beliefs often required human sacrifice at special times such as the construction of a temple, chief’s house or sacred canoes, or the installation rites of a new chief. The bodies were eaten as part of a religious ceremony, often accompanied by special chants and rituals.

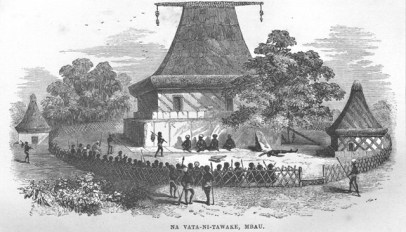

Bure Kalou (priest’s spiritual house)

Bodies of the victims, both men and women, were dragged to the bure kalou (priest’s spiritual house) to the beat of the death drum. The men performed the Cibi death dance and the women the obscene Dele or Wate dance where the bodies, living or dead, were sexually abused. Living captives were often severely tortured before being killed.

The bete, or priest, offered the bodies to the war gods, and then they were cut up and prepared for the oven using a bamboo knife. The bodies were cooked in earthen ovens and then eaten inside the bure kalou by the men of the clan. Women and children would eat if there was excess flesh.

The Fijian’s considered the priests’ hands and lips sacred or consecrated and attendants normally fed these men. These helpers were not allowed in the spirit house, so the priests fed themselves during cannibal feasts using special wooden forks. These special eating instruments were kept as sacred relics in the spirit house.

Priest Forks

Priest Forks

In the highlands of Vitievu, the bones of cannibalized enemies were placed as trophies in the forked branches of trees. On the coasts, where leg bones were used for making sail needles, trophies were the sexual organs or fetuses cut from corpses.

The slaughtered and gruesome remains were kept as treasures or heirlooms to recall the conquests. Common mementos include smoked snacks that could be nibbled on whenever a particularly hated enemy came to mind. A yagona cup made from the victim’s skull, enemy teeth made into a necklace, or hairdressing pins fashioned from long bones were other treasures.

The eating of the victims meant that they were destroyed and annihilated both physically and spiritually. It also meant that the person eating would inherit the victim’s knowledge.

The Fijian in Suva and Auckland Museum in New Zealand have massive collections of artifacts used in the rituals.

Christianity’s Influence

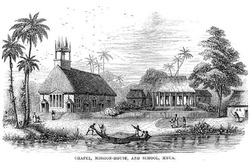

After several difficult and worrisome efforts to bring Christianity to Fiji, the Methodist Mission gained a foothold in 1835 when Methodist missionaries William Cross and Reverend David Cargill, together with their wives and a team of Tongan teachers landed in Lekeba, Lau. The conversion of the chiefs was the biggest obstacle to success, and so the mission spread its influence by widely dispersing English missionaries and Tongan and Fijian “teachers.” The conversion of one of the most important chiefs had a major influence on the wide-scale acceptance and conversion to Christianity.

Missionaries John Hunt and Thomas Williams

Some of the earliest missionaries were eyewitnesses to the horrors of the practice of cannibalism. John Hunt, one of the early missionaries wrote a book in 1859, “A Missionary Among Cannibals” (free online) and described Fijians digging up recently buried graves for human consumption. The cannibals also killed their sick and old, treated women as beasts of burden, and often strangled wives when their husbands died.

Wesleyan missionary Reverend Thomas Williams observed an incident and described it in his book “Fiji and the Fijian” published in 1858. A chief’s wife from a small island of Lekeba ran away in the middle of the night. After the chief’s men found her, she was brought back, and her arms were chopped off and cooked. She was forced to watch him consume her arms and died a few days later after she was baptized as a Christian.

Reverend Thomas Baker

Reverend Thomas Baker was just 35 years old while attempting to bring the Gospel to the village of Nubutautau in Fiji’s rugged highlands in 1867. He and seven Fijian converts were ambushed as they left the village, and then clubbed, cooked and consumed. Historians say the reason was the chief’s resistance to Christianity and complex tribal politics. Legend tells the story that Mr. Baker was murdered for breaking a taboo by taking a comb from the chief’s hair. Thomas Baker was the last missionary to be killed and eaten in Fiji.

Early Methodist Church in Fiji

The descendants of the Fijians who murdered these missionaries begged forgiveness from the descendants of Thomas Baker in 2003. “Thomas Baker died in this place, and we need to confess our sins,” said Elenoa Naiyaunsiaga. “It is time for repentance and an apology.”

Early Fijian Christians

Laisenia Qarase, Fiji’s Prime Minister also attended the ceremony and said, “In this area, the club and the old gods still ruled. Those who killed and ate the Reverend Baker and his believers would have felt they were defending themselves against threats to their established ways. We come here to apologize for that terrible moment in history.”

“Most Prolific Cannibal” as declared by the Guinness Book of World Records.

Ratu Udre Udre

The legend of Ratu Udre Udre, a particularly insatiable Fijian chief from Rakiraki, continues to intrigue and nauseate. In 1849, about nine years after Udre Udre’s death, missionary Richard Lyth recorded a gruesome discovery. A long row of 872 stones was on the chief’s tomb with many spaces in between indicated that stones had been removed. Udre Udre’s son told Lyth that his father indeed ate that number of human beings. They were victims of war, and he ate them all himself and shared with no one else. He ate nothing but human flesh and kept a box of preserved flesh, so he always had a steady supply on hand. Locals believe that Udre Udre ate somewhere between 872 and 999 people in his lifetime, therefore receiving the honor of being named Guinness World Records’ Most Prolific Cannibal.

- An article about the Suva Methodist Church can be found by clicking here: https://donnagawell.com/europe/australia/suva-fiji/

Most of the research for this article came from Yalo-i-Viti: A Fiji Museum, a book from the Fiji Museum in Suva written by Fergus Clunie, 2003.