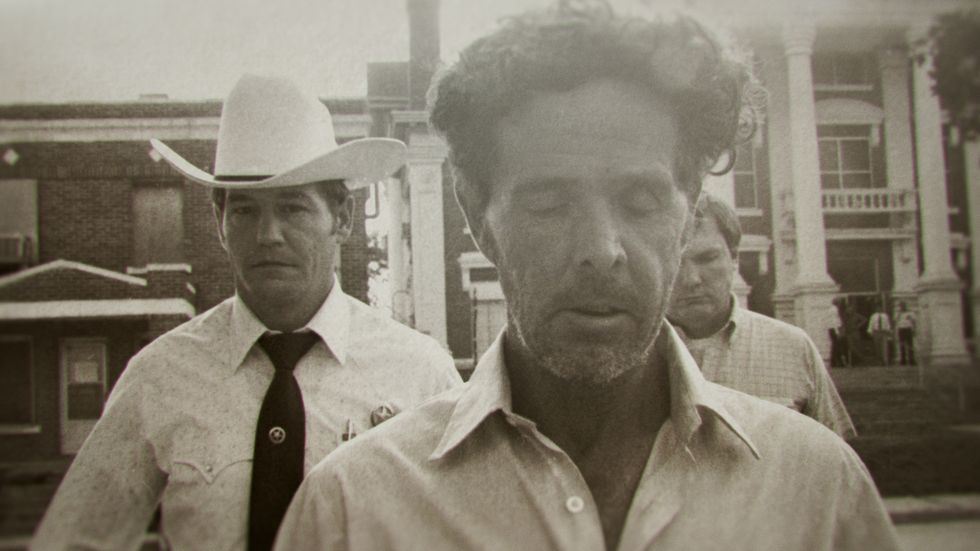

Henry Lee Lucas looked the part. He was a drifter with a history of violence, a spare scattering of teeth, and a drooping, weepy eye, and when he confessed to being the most prolific serial in American history, law enforcement and the public largely believed him. Lucas provided accounts that closed 197 murder cases, but now, a new five-part Netflix series is exploring the still-mounting evidence that almost all of these confessions were lies—and that hundreds of actual murderers have gone free.

Part of what makes The Confession Killer one of the most gripping products of the true crime media wave is the fact that, while Lucas almost certainly did not commit the vast majority all of the murders attributed to him, he was not an innocent victim. While nothing from the pathological liar’s account can be trusted, he likely killed at least three people, which means that technically, the serial killer mantle was well deserved. In 1960, a then-24-year-old Lucas murdered his mother, and served ten years in prison for second-degree-murder. In 1983, he confessed to the murders of his 15-year-old “girlfriend” and an elderly woman they’d worked for, and lead police to two sets of remains. The confessions began pouring forth after, during his arraignment for the murder of the elderly woman, Lucas stunned the court by asking: “What are we gonna do about these other 100 women I killed?”

According to Lucas’s confessions—which he eventually recanted—he had killed victims from all demographics and all around the country, deploying every method of murder from running them over with his car to stabbing them with a ballpoint pen, and engaging in depravities including necrophilia and cannibalism. The number of alleged victims ballooned to 350, and then 600.

The legendary Texas Rangers formed a task force to handle the confessions, and Lucas fielded visits from law enforcement officials from around the nation eager to close unsolved cases. Some provided him with crime scene photographs and other details related to open murder cases, which Lucas then helpfully regurgitated in his confessions. And while he kept up the stream of admissions, Lucas was treated as a star prisoner, navigating jail without handcuffs, kept in steady supply of cigarettes and his favorite strawberry milkshakes, and the subject of frenzied press attention.

“Henry never lived so good,” journalist Hugh Aynesworth says in the series. But there were skeptics, and Aynesworth was among them. After following Lucas’s paper trail, the reporter found that records proving that he was states away when some of the crimes he confessed to were being committed. A large-scale examinations of Lucas’s stories found that he would have had to drive hundreds of miles a day just to make it to all of his far-flung supposed murder sites.

Vic Feazell was a newly-minted District Attorney in McLennan County, Texas, when he began seeing Lucas on television, flanked by Texas Rangers and pointing out his alleged crimes scenes.

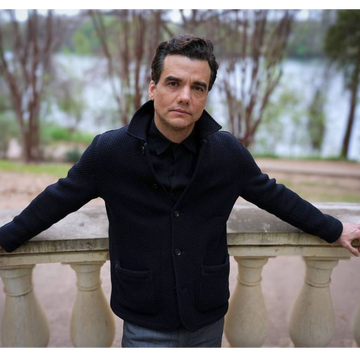

"And then the announcer would be saying, 'Henry Lucas has solved yet another murder,’” Feazell tells me in an interview. "I was thinking, ‘Wow. That's a lot of murders.”

Feazell became entangled in the Lucas saga after the serial murderer confessed to crimes in his county, including the 1978 rape and murder of Rita Salazar and the murder of her date, Frank “Kevin” Key. Feazell had as much motivation as any law enforcement officer to accept Lucas’ confession, which could have closed a horrifying case, and provided the ambitious young DA with a very public win. But Lucas’ confession didn’t ring true. "It would have been great to have my picture in the paper with a Ranger standing there next to me with the real-life version of Hannibal Lector,” he says. "But I believe in doing what's right. That's the way I was raised."

Feazell soon realized that his investigators' efforts to corroborate Lucas’s stories were being thwarted. When they attempted to digitally look up the killer’s files in the state and national criminal database, they were greeted with “access denied” messages. “That had never happened before,” Feazell tells me. And the national database shutdown was particularly alarming.

“Now, that scared us,” he says. "We knew then we were in pretty deep because we could understand how they might cut off our access in Texas, but how'd they do it nationally?”

And while some victims’ families found relief in authorities' accounts that Lucas had killed their loved ones, the family of Deborah Sue Agnew Williamson, who was slain in 1975, suspected from the beginning that Lucas’s confession was a fabrication. They had decades attempting to pressure local authorities to search for the real killer.

Lucas was convicted of a total of 11 murders and sentenced to death, though in 1998 his sentence was commuted in by Texas's then-governor George W. Bush. On average, the future president signed off on an execution every two weeks, and oversaw the killings of more prisoners than any governor before him. Lucas was the only condemned person whose death sentence he commuted, as evidence proved that he had been in a different state at the time of the murder for which he was sentenced to die. Lucas died in prison of congestive heart failure in 2001.

But The Confession Killer is at its most gripping when focusing not directly on Lucas, but on the law enforcement officials who seemed more concerned with having him close their cases than with the possibility that false confessions allowed murders to go free. "Case after case was being closed,” says Food, Inc. director Robert Kenner, who co-directed The Confession Killer with Taki Oldham. “And at some point, it became more convenient for law enforcement to disregard facts that became inconvenient to them.”

Dissenters describe lives upended by retaliation, with Aynesworth recounting a home invasion in which his valuables were left behind but his professional documents were taken, and Faezell eventually indicted on federal racketeering charges and that could have found him facing 80 years in jail—charges he says were retribution for his attempts to thwart the Texas Rangers handling of the Lucas case. Today, he’s in private practice, and hosts a podcast about the case that changed the course of his life and so many others.

But despite the fact that Lucas was no where near the mass murder he claimed to have committed, the myth of his dozens of killings has stuck. He was even the subject of a cult film, “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer.”

“Basically, at some point, the media and the public at large become invested in a story, and they don’t necessarily like to be corrected,” Oldham says. “People like that idea—people like to catch monsters.” And while the specter of one man, making his quiet way across America and killing hundreds of people, is terrifying, the likely truth that hundreds of killers are still at large is even more frightening.

The filmmakers hope that the release of this docu-series could spur police to reexamine Lucas’s alleged murders. DNA technology has already proven that 20 of the murders attributed to him were in fact committed by others—and that includes the murders of Salazar and Key. Feazell’s suspicion about the confession turned out to be right: In 2010, genetic evidence linked a man named Benny Tijerina Jr. to the crimes.