This is an extended version of a paper that I gave at the British Silent Film Festival Symposium at King’s College London on 7 April 2017. My book on Pandora’s Box (1929) is forthcoming from BFI Palgrave.

***

G. W. Pabst’s Die Büchse der Pandora (Pandora’s Box, 1929) is an adaptation of Frank Wedekind’s Lulu plays, but in many places a very loose one. Those German plays are about thirty years older than the film, a Weimar-era classic that marries traces of Expressionism with the late-1920s sobriety of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement. Pandora’s Box was filmed in Berlin, or at least in a former zeppelin hangar in Staaken, and its American star Louise Brooks identitfied its depiction of divergent sexualities and the sex trade with the city’s glamorous, permissive nightlife. Her evocative description of the city during the shoot, when she was staying at the famous Eden Hotel, begins: “Sex was the business of the town …”

“At the Eden Hotel, where I lived in Berlin, the café bar was lined with the higher-priced trollops. The economy girls walked the street outside. On the corner stood the girls in boots, advertising flagellation. Actors’ agents pimped for the ladies in luxury apartments in the Bavarian Quarter. Race-track touts at the Hoppegarten arranged orgies for groups of sportsmen. The nightclub, Eldorado, displayed an enticing line of homosexuals dressed as women. At the Maly, there was a choice of feminine or collar-and-tie lesbians. Collective lust roared unashamed at the theatre.”[i]

There is only one named location in the film, however, and it is in this place that the fictional narrative bumps into historical circumstance – so in this case, geography carries crucial meaning. The final act of Pandora’s Box the film, just like the final act of Wedekind’s play of the same name, takes place in London – in a slum district most likely in the east of the city. Jack the Ripper walks these streets, and our heroine Lulu, reduced to prostitution, encounters him with fatal consequences. This murder is her dramatic destiny, and to understand the film more fully, which was possibly the first cinema adaptation of the plays to feature London and the Ripper, we need to think about the British capital rather than the German one. To explore this topic I am going to examine three disappointing “misadventures” in London: the visits made by Frank Wedekind, Louise Brooks and the film itself.

“After lunch I get on the Underground at Charing Cross and travel to the Tower, look around the museum, the most boring and tasteless I have ever seen, travel under the Thames via London Bridge and come back home through the underworld, dine at seven o’clock and take the omnibus to the London Pavilion. Apart from a couple of authentic English children, I find nothing new and very little that’s congenial. I spend some time in a bar amid a pack of frightful whores, and go to bed at twelve o’clock.”[iii]

We can really only speculate on what “masses of material” Wedekind found in the British Museum reading room, but it seems reasonable to assume that he read about Jack the Ripper, an unidentified murderer thought responsible for killing several female sex workers between 1888 and possibly 1891 in the Whitechapel area, who was to become a character in his play. The news of the Ripper’s killings was fairly recent, in fact they happened after Wedekind began writing his plays, but a trip to the Museum would have provided some more detail about the nature of his crimes – specifically I think the amount of material widely shared in newspapers such as letters giving a supposed insight into the killer’s psychology, and also the distinctive mutilation of the bodies, which led to his gruesome nickname. Most of the victims were disemboweled, with organs including hearts and uteruses removed from the scene.

If his description is correct, then Wedekind’s trip to London’s “underworld”, or red-light district, was probably further west than the Ripper’s patch. As so often in the journal Wedekind here mixes enthusiasm with disgust in his accounts of paying or seeking to pay for sex, and the comparison between his disdainful sex tourism and his rather jaded review of the Tower of London is almost funny. We could speculate on whether his encounter with sex workers in two districts, feeds into his depiction of Lulu’s clients – a strange mix of rich and poor men, designed to mirror the suitors she has had earlier in the plays. Jack the Ripper, her final client, is the mirror of Schön, and often played by the same actor.

Did Wedekind use his “masses of material” in the finished play? We must remember that he was forced to edit and tone down the material in the Lulu plays to get them published and performed, but by naming his murderer as the Ripper, he introduces the idea of evisceration. There appears to be no explicit reference to Jack mutilating Lulu’s body in the play – unless you look for it. At the opening of the play’s final act, Lulu empties a basin of rainwater. Her death, when it comes, takes place just off-stage and when Jack re-enters the room he is carrying the basin, ostensibly to wash his hands. The first implication being that it was a bloody murder and the second that he has removed something from the scene. Edward Bond’s 1980 English translation chooses to make this explicit. Lulu cries: “He’s slitting me up!” and then Jack emerges with a newspaper parcel, saying: “When I am dead and my collection is put up for auction, the London Medical Society will pay three hundred pounds for the prodigy I have conquered tonight.”[iv]

There is no such hand-washing or parcel-carrying in Pabst’s Pandora’s Box. Brooks was dismayed by this, saying: “the movie should have ended with the knife in the vagina”.[v] However, the basin makes an appearance at the outset of the film’s final act, and I think there is in fact a suggestion of the Ripper’s bloody deed, which we will discuss after pudding.

***

We know that Brooks arrived in Paris in the December, was abandoned by her travelling companion Barbara Bennett, and fished out of the lobby of Edouard VII Hotel by the American film and theatre producer Archie Selwyn (Tallulah Bankhead nicknamed this extravagant man “Criminal-at-Large” and called him a “fascinating rogue”[viii] in her autobiography), who brought her to London and got her a job at the Café de Paris, a relatively new club. According to a frustratingly date-phobic history of the club, Champagne and Chandeliers: the Story of the Café de Paris, the cabaret budget was tight, especially in the early years. Brooks, who had been performing on Broadway in George White’s Scandals, is not named among the notable performers there and she would have been a featured dancer in a lineup of small acts, rather than a headliner. So when she recalls “I was living beyond my means – who doesn’t at seventeen? – in a flat at 49A Pall Mall”[ix] we must remember that her means were rather slight, despite that swanky address, and of course also, that she was eighteen years old.

What was inside the flat on Pall Mall? A Christmas pudding (she told Close Up that she “lived on it for a week”[x], although it is an unlikely delicacy for an American teenager, but perhaps she purloined one from the Café de Paris kitchen), also the January 1925 issue of Photoplay magazine (probably brought with her from New York – it was published on 15 December 1924) and a maid called Nellie.

That issue of Photoplay had Betty Bronson on the cover. Brooks and Nellie went together to see her in Peter Pan (Herbert Brenon, 1925), which was released in London on 22 January 1925. Before going to the pictures, they read what Brooks called “the Photoplay fairytale story of Betty’s rise to fame”. Here is that story in full:

“Betty Bronson, comparatively unknown seventeen-year-old screen actress, is as anxious as any film fan for the release of ‘Peter Pan’. Upon her success in that picture depends her future. She believes that the fairies will be kind.”[xi]

It is indeed a fairytale – but I suspect that this story aroused something like jealousy in Brooks, who, at the end of that month, gave up on London and called in a favour from her own fairy godfather. Paris suggests that Brooks was melancholic in London, and that’s why she was susceptible to fairytales – I would contend that although she may have felt dismayed, she used that disappointment to her own advantage, and began to calculate how to engineer her own “fairytale success”.

Rather than seeking to undermine the story of Brooks’s time in London, as recounted by Paris, I use this anecdote to illustrate a pivotal moment in her career, the system of patronage and support open to Brooks, and her determination to use it in order to make a career on stage or screen. She wrote in relation to Pandora’s Box: “I knew two millionaire publishers, much like Schön in the film, who backed shows to keep themselves well supplied with Lulus.”[xiii] She probably knew more than two. She was fairly candid about her relationship with Kahn, which saw them trading sexual favours and investment tips, and her dealings with Goulding, as one of

“a hand-picked group of beautiful girls who were invited to parties given for great men in finance and government. Walter Wanger[xiv] and Eddie Goulding screened them. We had to be fairly well bred and of absolute integrity – never endangering the great men with threats of publicity or blackmail. At these parties we were not required, like common whores, to go to bed with any man who asked us, but if we did the profits were great. Money, jewels, mink coats, a film job – name it.”[xv]

As she told Kenneth Tynan in 1979, “I was always a kept woman.”[xvi]

***

One might think that Jack the Ripper would be old news by the time Pabst filmed Pandora’s Box, but Lustmord, or sexually motivated murders, filled newspapers and narratives in 1920s Germany. To take just one example, Fritz Haarmann, ‘The Butcher of Hanover’, had sexually assaulted, murdered and mutilated at least 24 boys and young men between 1918 and 1924. Jack the Ripper himself made an appearance in the anthology horror film Waxworks (Paul Leni, 1924). Brecht and Weill’s The Threepenny Opera[xvii], playing in Berlin as Pandora’s Box was filmed, won praise for its portrayal of antihero Mack the Knife and the seedy London underworld. Neue Sachlichkeit artists Otto Dix and George Grosz dwelt on the theme with works including ‘Lustmord’ (1922), which directly refers to the Ripper’s crime scenes, and ‘John the Lady Killer’ (1918), respectively.

This is the most Expressionist part of the film too, as if an earlier cinematic mode suits the vintage material. In the Staaken version of London, Gunther Krampf’s cinematography[xviii] conjures the East End out of the barest spaces[xix], with extremely low and high-angled lights generating steep shadows and a criss-cross of constricting bars from the staircase, not to mention the evil, thick, swirling fog. Reports from those who worked with Krampf on later films recall him expertly manipulating fog and shadows.

In the finished film, while Lulu is being murdered, bloodlessly, with only a fallen hand to represent her passing, Schigolch, her father/pimp, retires to a local pub to eat a Christmas pudding. This is exactly as he promises to do in Wedekind’s play. The poet H.D., in a very bizarre interview with Pabst for Close Up magazine, quotes editor Kenneth Macpherson’s boast of his involvement in this pudding.

“Well, the dresser insisted that it was in a flat dish. I said a basin, and they brought a jelly mould … I drew one on the architect’s table. Pabst said ‘That is what I want. Round. Is it not, Herr Macpherson, round?’”[xx]

Pabst also appeared to listen to Macpherson on the subject of the proper garnish for this traditional British dish – a spray of holly. All very well, but the pudding in Pandora’s Box looks a little strange. It is basin-shaped, but the sphere in question is flatter, and more like a wash-basin than a pudding-basin, and that is not holly on top but mistletoe, the same poisonous berries that the Ripper holds aloft over Lulu’s head before he kills her. Schigolch, after sending his daughter or ward into the arms of a killer, plunges his spoon into this grotesque pudding, entirely unperturbed. Thus Schigolch, the true villain of this piece, shares a taste of the Ripper’s vicious crime.

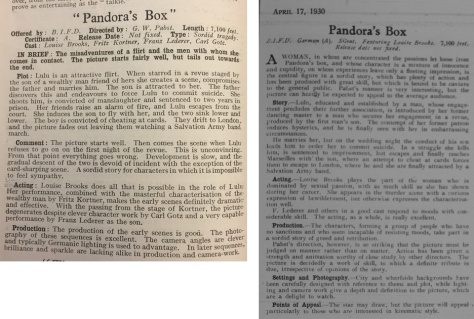

If this is Pabst’s attempt to sublimate the Ripper’s modus operandi through symbolism, it may have also have been his attempt, like Wedekind before him, to pre-empt the censor. But by the time Pandora’s Box reached London, the censors had already gone to town. The print that was screened at a trade show in April 1930 (that’s more than a year after its Berlin premiere) was almost certainly the same version that had been shown in New York in December of 1929. There, as Mordaunt Hall noted in his review:

“In an introductory title the management sets forth that it has been prevented by the censors from showing the film in its entirety, and it also apologizes for what it termed ‘an added saccharine ending’.”[xxi]

The cut-down version of the film excises the lesbian character Countess Geschwitz, and removes other uncontroversial incidental business such as Siegfried Arno’s comedy routine backstage at the revue. It also deletes the very reason for Lulu and co to wash up in London – Jack the Ripper himself. In this version, there is no murder and Lulu and Alwa are inspired to make a fresh start instead after listening to the Salvation Army band.

“A brilliant idea – Pandora’s Box with the lid off! Yes, in England. You would have thought the censor would have kept the lid firmly on Pandora’s box. But he went one better. He took the lid off, let everything out and then showed us the film to let us see there was nothing in it. Result, everyone thinks it a duller film than the scenario made it and the trade papers were unable to recommend it … Pandora’s Box as it will be seen in England gives no idea of the film it was when Pabst finished it. Pabst’s gift is the gift of wholeness, completeness, actual and psychological. Alter it, upset one vibration, you have ruined a piece of fine work.”[xxii]

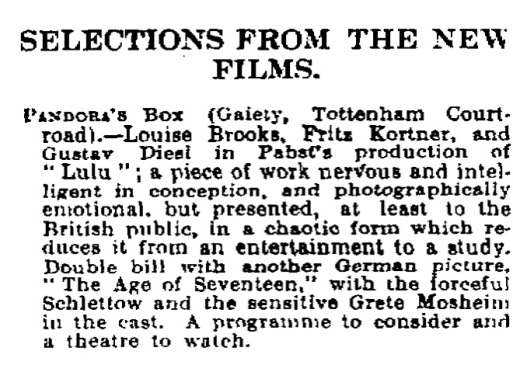

Herring made similar, but less passionate comments in the Manchester Guardian both before and after the trade show, condemning the cuts, although also describing the scenario as “stupid” and Brooks as “wooden”.

By 1930, it was an oddity, one of the few venues in London still exclusively showing silent films – though without an orchestra pit to support the bigger releases. It was remodelled in 1933 to reopen as a newsreel cinema, on which occasion, Ralph Bond wrote a little eulogy of the Gaiety for Close Up, describing the venue’s creaky piano, dusty seats, and frequently snapping film. In this cinema, he wrote, “black-hatted intellectuals would rub shoulders with the denizens of Tottenham Court Road’s back streets, admiring the genius of Pabst”[xxxi].

It’s a shame that Pandora’s Box never got a fair screening in a location so important to its narrative. As late as 1968 the NFT was showing a print that promised to be almost complete but really wasn’t – it was a partially corrected version of the French release of the film, Loulou, which had likewise been heavily censored. However, there is something grimly appropriate about its run at the Gaiety, facing a mixed, if select, crowd of cinephiles and pleasure-seekers. Just like Jack the Ripper emerging from Gunther Krampf’s Expressionist fog, Pandora’s Box ventured to London as an anachronism, out of place and out of time. Equally today, when we celebrate the uncanny modernity of this late-silent classic, we do well to remember its roots in the grotty history of Victorian London.

[i] Louise Brooks, Lulu in Hollywood: Expanded Edition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 1982), p.97

[ii] Wedekind, Frank, Diary of an Erotic Life, Edited by Gerhard Hay, translated by W. E Yuill (Cambridge: Basil Blackwell 1990), p. 234

[iii] Ibid., p. 235

[iv] Frank Wedekind, Plays: One, translated and introduced by Edward Bond and Elisabeth Bond-Pablé (London: Methuen second edition 1993), pp. 208-209

[v] Kenneth Tynan, ‘The girl in the black helmet’, The New Yorker, 11 June 1979, p. 57

[vi] Barry Paris, Louise Brooks: a Biography (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), p. 77

[vii] Ibid., p. 78

[viii] Tallulah Bankhead, Tallulah: My Autobiography, (Jackson: University of Mississippi: 2004, originally published 1952), p. 161

[ix] Letter to William K. Everson, quoted in Paris, p. 78

[x] H. D., ‘An appreciation’, Close-up, Vol IV No3, March 1929, p. 57

[xi] ‘Two Peter Pans Bid for Film Fame’, Photoplay, January 1925, p. 35

[xii] Paris, ibid., p. 78 He also misnames the club’s owner Major Robin Humphreys as Captain Lyle Humphreys.

[xiii] Brooks, p. 97

[xiv] One of Brooks’s lovers, who also who arranged her Paramount audition.

[xv] Louise Brooks, letter to Kevin Brownlow, 27 April 1967, quoted in Paris, p. 72

[xvi] Kenneth Tynan, ‘The girl in the black helmet’, The New Yorker, 11 June 1979, p. 65

[xvii] Filmed by Pabst in 1931.

[xviii] Krampf had previously photographed some typically Expressionist films such as The Hands of Orlac (Robert Wiene, 1924) and The Student of Prague (Henrik Galenn, 1926) but not as has often been cited, Nosferatu (F. W. Murnau, 1921) http://www.filmportal.de/person/guenther-krampf_ba9046b3a72a44db8628bda224d9a990

[xix] See Amy Sargeant, ‘Night and fog and benighted ladies’, Adaptation, Vol. 3 Issue 1, 2010

[xx] H. D., ibid., p. 57

[xxi] Mordaunt Hall, ‘The Screen’, New York Times, 2 December 1929 http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9E06E2D61739E43ABC4A53DFB4678382639EDE If you want to know how that apologetic title got there, well you have to read my book – BFI/Palgrave, forthcoming.

[xxii] Robert Herring, ‘For adolescents only’, Close Up, May 1930, pp.23-24

[xxiii] ‘Pandora’s Box, Kine Weekly, 17 April, 1930

[xxiv] ‘Pandora’s Box’, The Bioscope, v83 n1228 16 Apr 1930, pp. 34

[xxv] Herring, ibid., p. 24

[xxvi] A., A. “A Grim German Film.” Daily Telegraph, 4 Aug. 1930, p. 4.

[xxvii] C. A. Lejeune, ‘The poor man’s holiday’, The Observer, 24 August 1930, p. 6

[xxviii] Ibid.,

[xxix] ‘A bandit as you like him’, Film Weekly, 14 June 1930, p. 24

[xxx] Matt Houlbrook, Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957 (Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press 2005), p. 58

[xxxi] R. Bond, ‘The last of the silents’, Close Up, March 1933, p.78

- With thanks to the British Silent Film Festival, Lawrence Napper, Bryony Dixon, Martin Koerber, Thomas Gladysz, Fern Riddell, Chris O’Rourke’s London’s Silent Cinemas project and De Montfort University and University of Stirling’s AHRC-funded project investigating British Silent Cinema and the Transition to Sound, 1927-1933.

- My book on Pandora’s Box is forthcoming from BFI Palgrave as part of its Film Classics series.

- You may also be interested in a piece I wrote about Louise Brooks and Hollywood for Little White Lies.

Thanks Pamela, what a brilliant paper! And now I don’t feel so bad at missing the Friday at the BSFF Symposium…

Thanks John, and thanks from all of us for salvaging the piano situation on Thursday. Hope you are enjoying your time with Ivan!

Well, I’m enjoying Mr Mousjoukine, could do with a few more people doing likewise. Had to laugh at the bit in your paper where you write “Daily Mail is more than happy to use her image on the slightest provocation” Plus ça change…