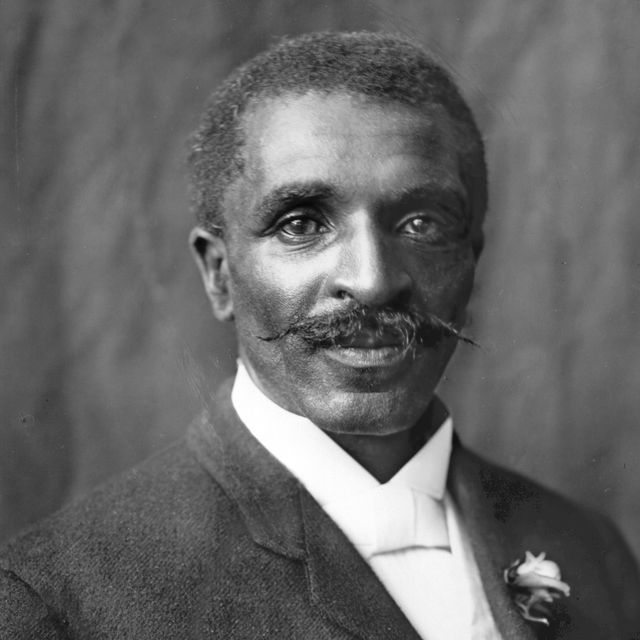

George Washington Carver is known for his work with peanuts (though he did not invent peanut butter, as some may believe). However, there's a lot more to this scientist and inventor than simply being the "Peanut Man." Read on for seven insights into Carver, his life and his accomplishments.

He was known as the young 'plant doctor'

Even as a child, Carver was interested in nature. Spared from demanding work because of his poor health, he had the time to study plants. His talents flourished to the extent that people started to ask him for help with their ailing vegetation.

In a 1922 interview, he recalled, "Often the people of the neighborhood who had plants would say to me, 'George, my fern is sick. See what you can do with it.' I would take their plants off to my garden and there soon have them blooming again ... At this time I had never heard of botany and could scarcely read."

Though Carver would gain new skills over the years, the path he'd follow in life was clear.

Appearing before Congress made him the 'Peanut Man'

Besides peanuts, Carver's research also involved clays, seeds and sweet potatoes. So why is his name associated with just one legume? It's thanks in large part to an appearance he made before the House Ways and Means Committee.

In 1920, Carver spoke at the United Peanut Association of America's convention. He was such a success that the group decided to have him tell Congress about peanuts and the need for a tariff in January 1921.

Though his congressional presentation didn't start out well — the representatives weren't predisposed to listen to a Black man — Carver ended up winning over the committee. They were drawn into testimony that covered many of the products Carver had created with peanuts, such as flour, milk, dyes and cheese, and ended up inviting him to take as much time as he needed to talk.

After his appearance, peanuts and Carver were intertwined in the public's mind. The scientist didn't mind the association; however, when asked in 1938 if his work with peanuts was his best, Carver answered, "No, but it has been featured more than my other work."

READ MORE: How George Washington Carver Went From Enslaved to Educational Pioneer

He believed peanuts could fight polio

Polio victims were often left with weakened muscles or paralyzed limbs. Carver felt that peanuts — or rather peanut oil — could help these people regain some lost function.

In the 1930s, Carver began to treat patients with peanut oil massages. He reported positive results, which in turn made more and more people want to undergo the treatment. Even Franklin D. Roosevelt joined in; gifted with the oil by Carver, he told the scientist, "I do use peanut oil from time to time and I am sure that it helps."

Unfortunately, despite the improvements that Carver witnessed and reported, there was never any scientific evidence that peanut oil actually helped polio victims recover. Instead, the patients may have benefited from the massage treatment itself, as well as the attentive care that Carver provided.

He didn’t write down details

Though Carver worked on many products, both peanut and non-peanut, he didn't see the need to keep detailed records.

In 1937, Carver was asked for a list of the peanut products that he'd developed. He wrote in reply, "There are more than 300 of them. I do not attempt to keep a list, as a list today would not be the same tomorrow, if I am allowed to work on that particular product. To keep a list would also give the Institute a great deal of trouble, as people would write wanting to know why one list differs from another. For this reason we have stopped sending out lists."

However, Carver did see the point in writing down advice and recipes, which he shared in agricultural bulletins such as "How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it For Human Consumption" (1916). So while you can't see all of Carver's formulas, Carver's instructions for peanut soup, peanut bread, peanut cake and more are available!

He was a well-connected man

Carver was a friend, colleague or associate to a veritable "Who's Who" of the 20th century. This began in 1896 when Booker T. Washington hired him to oversee the agricultural department at the Tuskegee Institute.

Between 1919 and 1926, Carver corresponded with John Harvey Kellogg (of cereal fame), as they shared an interest in food and health. Carver and automaker Henry Ford quickly struck up a friendship after meeting in 1937. Carver would stop by Ford's laboratory in Dearborn, Michigan, and Ford himself visited Tuskegee in Alabama. Ford also gave the funds to install an elevator in Carver's dormitory as the scientist grew weaker in his later years.

Carver's connections also extended outside the United States. Supporters of Mahatma Gandhi asked Carver for advice about how Gandhi could build up strength in between hunger strikes. And the Indian leader wrote Carver to thank him for sending agricultural bulletins.

READ MORE: George Washington Carver’s Powerful Circle of Friends

He considered weeds 'nature’s vegetables'

Along with peanuts, Carver felt that weeds — or "nature's vegetables" — were a nutritious and undeveloped food source for America. Carver once noted, "There is no need for America to go hungry as long as nature provides weeds and wild vegetables..."

Ford shared this appreciation for wild greens. He'd happily eat sandwiches made by his friend Carver, which contained ingredients such as wild onion, peppergrass, chickweed, wild lettuce and rabbit tobacco.

But before you rush outside to harvest your next salad or sandwich filling, you should know that not everyone was a fan of Carver's weed-based preparations. "They tasted terrible and if we didn't say they were good he got mad," a former student of Carver's complained in 1948.

He cared about people, not money

Throughout his life, Carver's actions demonstrated how little he cared for money. For example, he turned down a six-figure job offer from Thomas Edison. Carver also didn't spend much on clothes (and consequently was always shabbily dressed).

In addition, Carver filed only three patents on the products he'd developed. As he explained, "One reason I never patent my products is that if I did, it would take so much time I would get nothing else done. But mainly I don't want any discoveries to benefit specific favored persons. I think they should be available to all peoples."

In 1917, Carter revealed what motivated him: "Well, some day I will have to leave this world. And when that day comes, I want to feel that my life has been of some service to my fellow man." When he passed away in 1943, it would seem he had lived just such a life.