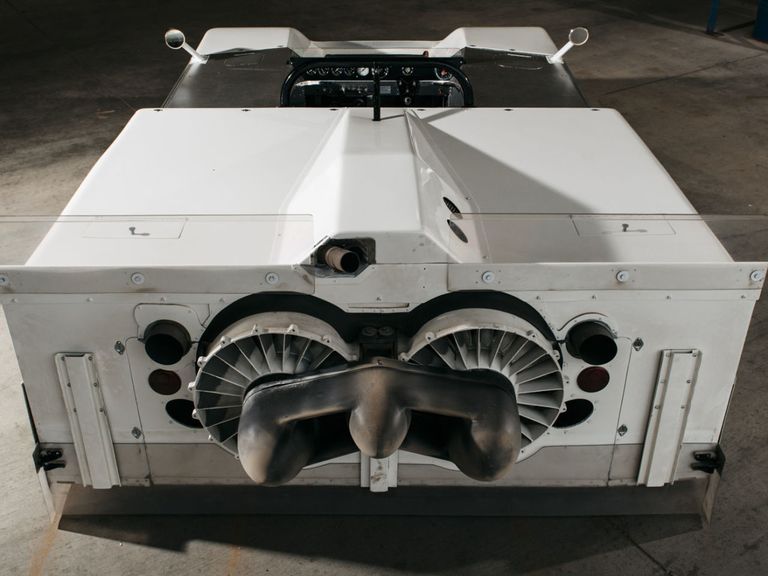

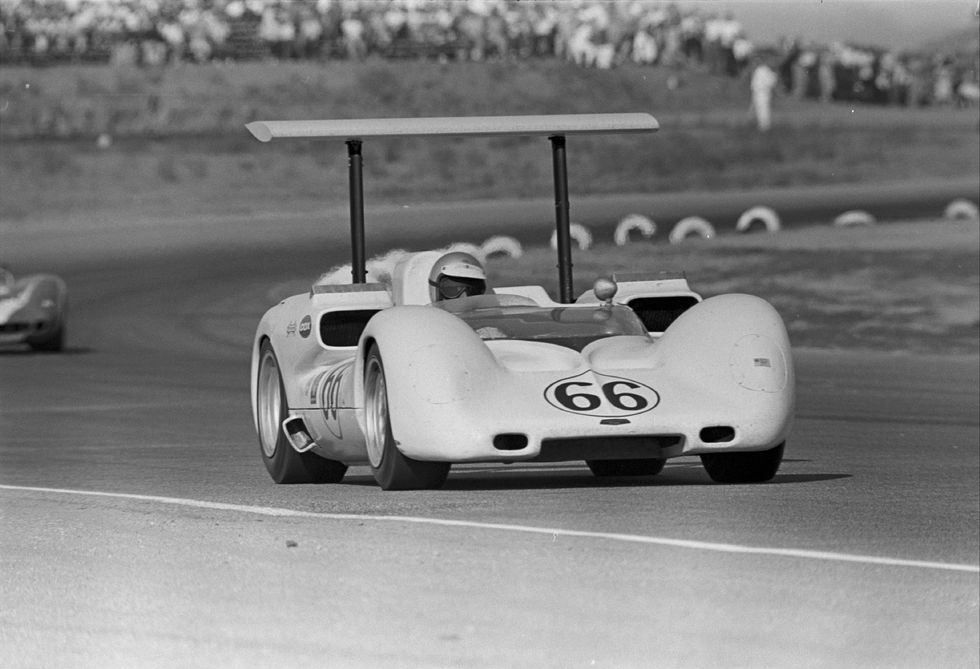

On July 12, 1970, a white Chevrolet pickup truck towing a trailer pulled into the paddock at Watkins Glen International Raceway for the third Can-Am race of the season. A small crowd gathered to watch the team unload. The small white race car atop the trailer looked like nothing else: no wing, no velocity stacks, no scoops or side pods or wild cutaways or NACA ducts, hardly a curve of any kind. The rear wheels were encased in bodywork as flat and unadorned as a diner kitchen. "Like the box it came in," the crowd observed. They moved to the back of the car: two fans like jet engines, supported by three black Dagmar-shaped cones, looking more like a Star Wars escape pod than a road-going automobile.

Who knows what the crowd must have thought. Who knows what the other drivers and team managers and pit chiefs must have thought. Dear God! Can-Am was famous for having no-holds-barred technical expertise, but this was something else: every other car looked like phallic fantasy, all elongated curves and swoops and short, stubby wedges, like 6th-grader math class daydreaming rather than real race cars, but here the Chaparral 2J was square, bulky, straight-paneled and utterly, breathtakingly, rational. The crowd had seen nothing like it.

Jim Hall was born in 1935 in Abilene, Texas, to a successful family that made its fortune in the oil boom. He was the youngest of three brothers. The family moved all around the West; Hall grew up in Colorado and New Mexico before returning to West Texas. Like his brothers Charles and Dick, he was expected to go into the family business. Jim enrolled in Caltech to study geology to do just that—but a month into his freshman year his parents and sister died in an airplane crash.

Jim inherited a fortune. His brothers took over the oil business, and by sophomore year, Jim switched his major to mechanical engineering: "I wasn't interested in memorizing crystal structures," he told his former engineering department, "I got into the upperclassmen classes in engineering and started to really enjoy school—mechanics and dynamics and materials and thermodynamics." He started racing cars around then: his brother Dick had moved to Dallas to help another fellow Texan open up Carroll Shelby Sport Cars, and he drove and graduated in 1957 with a bachelors degree in mechanical engineering.

Hall bought a plot of land on the outskirts of Midland and paved a two-mile racetrack and garages, a gathering spot for burgeoning SCCA Midlanders named Rattlesnake Raceway.

One of these guys was James Sharp. Sharp was another Texas oilman who went all in to the racing game: he competed in Formula One at the same time as Hall, racing a Cooper Monaco nicknamed by the press "Old Dirty," to his chagrin. Born on New Years Day, hence his nickname Hap ("Happy New Year"), the broad-shouldered Sharp also played polo, gambled, raced powerboats (he won the US National Outboard Racing Championship) and eventually amassed over 100,000 acres of land in South America.

Hall and Sharp commissioned the racecar builders Dick Troutman and Tom Barnes to build a new American racer: the Chaparral. It was a very conservative race car: front-engined, tube-framed, with an aluminum body and a Chevrolet 318ci small-block. On Hall's first outing with the Sports Car Club of America, at Laguna Seca Raceway in 1961, he finished an impressive second—behind a Maserati Birdcage.

Less than two years later, the pair bought the rights to the name and debuted the Chaparral 2: a mid-engined, fiberglass-bodied monocoque chassis. It first raced in 1963.

Note the timeline. In 1966, they debuted the adjustable wing. That same year, Chaparral won the grueling Nurburgring 1000km with the closed-cockpit 2D. By 1967, Chaparral's moveable wings had been banned by the FIA. And it was in 1970 that Chaparral debuted its greatest creation: the stealthy 2J, the "sucker car," a car too far ahead of its time to be from this planet. From Troutman and Barnes to the 2J was less than a decade.

The Chaparral 2J is powered by an aluminum Chevrolet ZL1 engine, 427 cubic inches and producing 650 horsepower at 7000 RPM. It is paired to a clutchless semi-automatic three-speed transaxle. With a fiberglass resin body, it weighs hardly over 1800 pounds. The auxiliary engine, mounted behind the rear wheels, is a Rockwell JLO 247cc two-stroke, two-cylinder, 45-horsepower engine, usually found powering snowmobiles. At full power, it makes an ear-splitting, high-pitched drone, like the buzzing of mechanical wasps from hell. The two rear fans are lifted from a M-109 Howitzer and capable of pushing out 9650 cubic feet of air per minute at 6000 RPM. With the Chevrolet engine off, rumor has it, they can even push the car forward at 25 to 40 miles per hour. The fans draw air from the bottom of the car and send it—along with dust, debris, oil sprays, and the occasional grass clippings—to the back, presumably into the faces of other drivers. These drivers inevitably raised a stink to Hall about it: we can't see when you're in front, we're getting sprayed with all of this debris. "Well," said the taciturn Hall, "why don't you pass me then?"

There's more. To create a negative pressure vacuum that would suck the car to the ground, the car featured skirts around the rear three-quarters of the car. Hall approached General Electric to use its relatively new invention, Lexan: a polycarbonate plastic material that was light, flexible, strong, and most importantly, unbreakable. The skirts moved up and down through a system of cables, pulleys, and machined arms that were bolted to the suspension. The result was a near-constant alignment to the road surface. With the fans on, the car would hunker down by two inches.

The result of all this complexity was constant downforce—at any speed, through any corner. Theoretically, the 2J could generate up to 2200 pounds of downforce. Fully fueled, the 2J could pull from 1.25 to 1.5gs through turns. "We can go full throttle without wheelspin or uncontrollable oversteer," Hall told Competition Press in 1970. "You can't imagine the car can stop as fast or corner as hard as this one does."

But in addition to the already-fraught complexities of a Can-Am car—engine, brakes, cooling, light weight, aerodynamics, reliability—there were also two other systems to be sorted: the fan system, with its frequently unreliable secondary engine; and the Lexan skirt system, which had to move in perfect sync with the car's suspension, neither cracking nor breaking off.

"I think the hardest part about it was that it was like having two cars, but in one space," Hall told Racer Magazine earlier this year. "General Motors thought we'd have a hard time keeping stuff under wraps. . . if we didn't go run it, someone else might jump in and race the concept before us."

The car missed the first two races of the 1970 season. Jackie Stewart went to America to drive the 2J at Watkins Glen, a one-race deal; he qualified third. "The car's traction, its ability to brake and go deeply into the corners, is something I've never experienced before in a car this size or bulk," he wrote in his book Faster!. "Its adhesion is such that it seems to be able to take unorthodox lines through turns, and this, of course, is intriguing."

But in practice, the car kept pulling in dirt, disrupting the belts and overheating the auxiliary engine. During the race Stewart was closing into Dan Gurney when he was forced to pit, and then, back out for a scant seven more laps, the brakes failed.

The team missed the next three races. Vic Elford campaigned the 2J in the remaining four events. At Laguna Seca Raceway, the second-to-last race, Elford was the only driver to qualify under a minute—even though he had never driven the track before. The next day, he smashed McLaren's 1969 record. The McLaren camp considered protesting. They didn't need to. A connecting rod punched through the block in the mighty Chevrolet engine, and the team simply didn't have enough time to take off the bodywork and swap the engine. The team moved on to Riverside, the last race of the season. Once again, Elford qualified first. The Rockwell JLO engine broke a crankshaft but the team was able to patch it up just before the race. After the green flag dropped, on just the second lap, the auxiliary engine died—this time for good. The fan system was all but useless and the car dropped out for the last time.

In 1966 the Chaparral 2E was the first race car in the world to be fitted with a wing, sucking the car to the ground from the rear suspension mounts. It ushered in a new era for race cars, one that the FIA begrudgingly allowed. ("I saw it written somewhere, 'isn't it wonderful what Colin Chapman invented, that wing he put on the car in 1968?'" Hall reminisced. "I said, 'it took them until 1968?'") Hall added instant adjustability to these tall, spindly wings, able to change their angle at the press of a pedal. The FIA banned that innovation. He retrofitted the adjustable wing, along with an unusual automatic transmission to free up the clutch pedal, to the 2D endurance racer. That was banned by the FIA, too.

Hall, always scanning the horizon for that unfair advantage, had to figure out a way to generate downforce without the sky-high wings that built his reputation. Hall and Sharp had already pushed the limits. Can-Am, seemingly, had no rules. But no good idea lasts for long in racing.

Despite being a close friend of the Halls, Bruce McLaren led the protests against "movable aerodynamic devices." Just before the start of the 1970 season, McLaren was killed testing his next car, but the team watched the 2J qualify seconds faster, take pole position, and eventually break down—and knew that the threat was imminent. They carried on the fight. The SCCA acquiesced, and the whole thing—fans, skirts, and Lexan—counted as "moveable aerodynamic devices."

"We ran up against that mob mentality with the 2E, too," said Hall. "I've been asked before what was said about the 2J to get it banned, but we weren't invited to those meetings. But I will say we were concerned enough about it that we invited the SCCA [Can-Am's sanctioning body] to Texas to take a look at it before we brought it to the races, and we got their opinion on it. They said it was legal. So it was a bit of a surprise to me that they ended up banning it. That was my biggest disappointment."

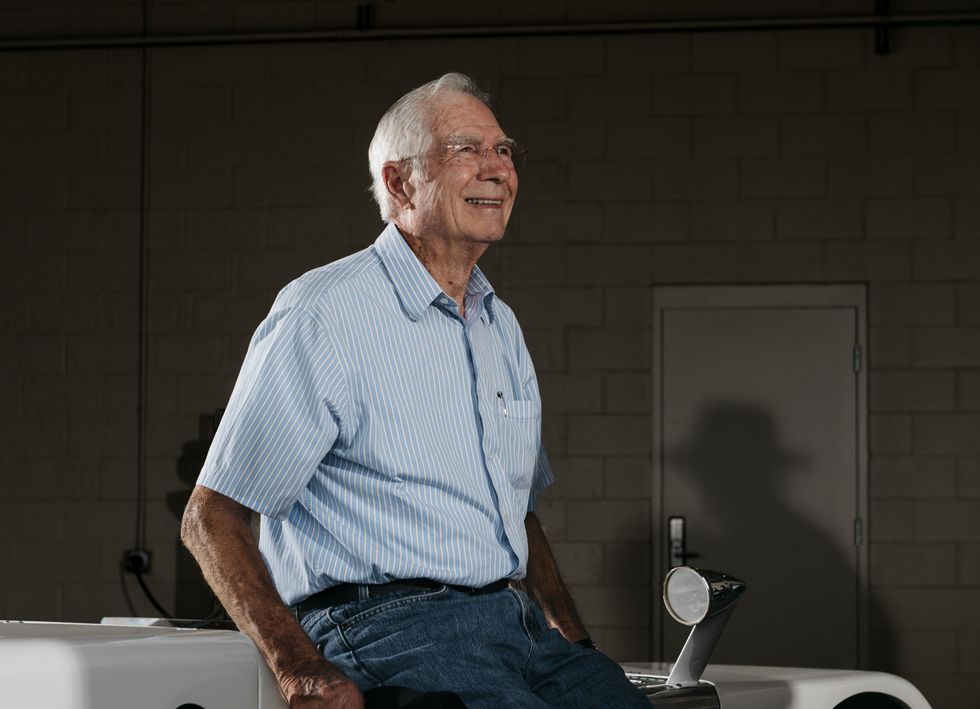

Hall was tired of fighting battles. He bought out Hap Sharp for the rest of Chaparral, and eventually moved on, winning the Indianapolis 500 and the CART Championship in 1980 with the 2K But that is a story for another time. Hap Sharp lived out a quiet life in South America until 1993, when faced with terminal cancer, he committed suicide. Jim Hall stayed in Midland. And so did his cars.

Every year, the Permian Basin Petroleum Museum in Midland, Texas, hosts a Live Drive gala for the dedicated members of the Chaparral Fan Club. (There's a double meaning.) The Fan Club is a devoted bunch: many remember seeing the Chaparral cars at the track as kids, teenagers. They drive in from Illinois and California and points between for the chance to see one of Chaparral's cars roaring around the Museum's rotunda, decades later. This year it was the 2J. We couldn't miss it.

Hall has never sold any of his race cars. For years, they sat in his garage right off Rattlesnake Raceway. They are worth untold millions—but to the man who built them, what does that matter?

In 2004, the Museum took over the Chaparral collection, building a dedicated wing for the seven remaining cars. For a team that arose from oil money, there is no more fitting home.

Hall maintains that all of his cars be kept running, and for this task he enlisted Jim Edwards, Hall's personal mechanic, to bring the cars back up to running order. "They were all mostly together," said Edwards, who used to test cars with Hall at Rattlesnake Raceway. "Some of them ran well, some of them didn't run well, so we just went through them. What I primarily did was on the suspension pieces, we Magnafluxed everything and repainted it and then reassembled everything, got it so that they would be roadworthy. And then the engines that didn't run, we tuned them up and got them ready to go too."

The cars were kept as original as possible, though one was repainted. (A replica 2E sits in the Chaparral Gallery as a photo car: you can put on a cowboy hat and squeeze right into it. Photographer Kevin McCauley and I did just that.) Incidentally, the 2J was the hardest car he worked on.

The 2J was in fine fettle that day, crowd gathering around the entrance of the Petroleum Museum, baking in the West Texas heat. Museum specialists fired up the the big-block Chevrolet V8 with a roar. Hall climbed in. The dust kicked up almost instantaneously. The sound of the Rockwell JLO engine howled and whined with a constant drone, a sound that bored into one's brain, portending doom and chaos and everything in between. No wonder McLaren protested, having to hear that two seconds ahead into The Boot at Watkins Glen. . .

Hall hadn't driven it in thirty years. But to him, in that all-brief moment, it felt just right.

"It sticks so good that I never did learn how to drive it deep enough into the corners," said Hall. "You look at the corner, and you put your foot on the brake, and it stops. And you look at the corner, and it's still out there. How did that happen?"

"We had a joke about it: if you let the skirts down, where you didn't have hardly any gap to the ground, you could create a heck of a lot more suction under it—and we calculated, we could actually drive it on the wall around Sebring."

"I'm sure you took exception to Enzo Ferrari's statement that aerodynamics are for people who can't build engines," asked a guest.

"That's a cute statement, by the way," replied Hall, "and I don't know if he made it or not. Do you think he did?"

I don't know, the man said.

"I don't know either."

Chaparral may have been a team that strove too fast. Tempered by ambition, plagued by unreliability, its cars and the engineers who built them were always clamoring for one more year, one more turn around the sun to work things out. Next season, always next season! Instead, Chaparral was always a proof-of-concept, always in progress.

"When you see the Chaparral 2J, at Can-Am races, look it over carefully," said the program for the 1970 Monterey Castrol GTX Grand Prix—where the 2J had nearly achieved its proof-of-concept potential. "You won't see any rear wheels. When it starts, there'll be a different sound. first, the sound of the booming ZL1 engine. Then the raucousness of the auxiliary engine and fans — earsplitting. And when all of this happens, you'll see the 2J hunker down as the suction takes hold. Out on the course, well you wait and see.

"There's never been a Can-Am car like the Chaparral 2J. The incredible Chaparral 2J."