Femme Fatale (2002 film)

| Femme Fatale | |

|---|---|

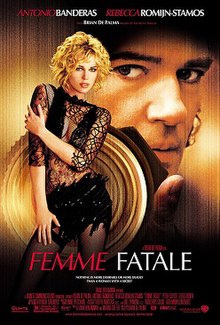

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Brian De Palma |

| Written by | Brian De Palma |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Thierry Arbogast |

| Edited by | Bill Pankow |

| Music by | Ryuichi Sakamoto |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 110 minutes |

| Countries | |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $35 million |

| Box office | $16.8 million |

Femme Fatale is a 2002 erotic thriller film[2][3] written and directed by Brian De Palma. The film stars Antonio Banderas and Rebecca Romijn-Stamos. It was screened out of competition at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival.[4]

Upon its release, Femme Fatale received mixed reviews from film critics and became a box office flop. However, the film has since been better received by many critics and gradually regarded as a cult classic.[5][6][7][8] Warner Bros. had included the film in the catalogue of Warner Archive Collection.[9] In May 2022, Shout! Factory (under license from Warner Bros) released a special edition Blu-ray of the film.[10]

Plot[edit]

Mercenary thief Laure Ash is part of a team executing a diamond heist at the Cannes Film Festival. The diamonds are located on a gold ensemble worn by model Veronica, who is accompanying real-life director Régis Wargnier to the premiere of his film East/West. Laure seduces Veronica in order to obtain the diamonds, during which her accomplices "Black Tie" and Racine provide support. However, the heist is botched and Laure ends up double-crossing her accomplices and escaping to Paris with the diamonds. In Paris, a series of events causes Laure to be mistaken for a missing Parisian woman named Lily who had recently disappeared. While Laure luxuriates in a tub in Lily's home, the real Lily returns and commits suicide while Laure secretly watches, providing Laure the opportunity to take her identity for good, and she leaves the country for the United States.

Seven years later, Laure (in her identity as "Lily") resurfaces in Paris as the wife of Bruce Watts, the new American ambassador to France. After arriving in France, a Spanish paparazzo named Nicolas Bardo takes her picture. The picture is displayed around Paris, and Black Tie (who has coincidentally been released from prison seven years after being arrested for the heist) spots Bardo's photo while in the middle of killing a woman, seen talking earlier with Laure at a café, by throwing her into the path of a speeding truck. With Laure exposed to her vengeful ex-accomplices, she decides to frame Bardo for her own (staged) kidnapping. Bardo is further manipulated by Laure into following through with the "kidnapping", and in the process, they begin a sexual relationship. The pair eventually meet with Bruce for a ransom exchange; however, Bardo has a crisis of conscience at the last moment and sabotages the scheme. In retaliation, Laure executes both Bruce and Bardo, only to be surprised by her ex-accomplices afterwards who promptly throw her off a bridge to her seeming death.

In an extended twist ending, the entirety of the film's events after Laure enters the tub in Lily's home are revealed to be a dream. In reality, Laure spies Lily entering the home as before, but this time Laure stops Lily from committing suicide. Seven years later, Laure and Veronica, who is revealed to have been Laure's partner all along, chat about the success of their diamond caper. Black Tie and Racine arrive seeking revenge, but they are indirectly killed by the same truck that killed Veronica in Laure's dream. Bardo, witnessing all these events, introduces himself to Laure, swearing that he has met her before, with Laure replying "Only in my dreams."

Cast[edit]

- Rebecca Romijn as Laure Ash / Lily Watts

- Antonio Banderas as Nicolas Bardo

- Peter Coyote as Ambassador Bruce Hewitt Watts

- Eriq Ebouaney as Black Tie

- Édouard Montoute as Racine

- Rie Rasmussen as Veronica

- Thierry Frémont as Inspector Serra

- Gregg Henry as Shiff

- Éva Darlan as Irma

- Fiona Curzon as Stanfield Phillips

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

The film was a box office bomb, taking in less than its production costs worldwide.[11] It grossed $6.6 million domestically and $10 million internationally for a worldwide total of $16.8 million.[12]

In North America, the film played very well in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Toronto and Chicago, but also played weakly in the mid-section of the country.[13]

The film generated more than $19.66 million in home video rentals in the United States (significantly higher than the film's United States box office gross).[14]

Critical reception[edit]

The film received mixed reviews during its theatrical release. The film has a 49% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 137 reviews, with an average rating of 5.5/10. The website’s critics consensus reads, "The thriller Femme Fatale is overheated, nonsensical, and silly."[15]

Among the critics who praised the film were A.O. Scott of The New York Times[16] and Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times,[17] the latter of whom gave a 4-star review and called it one of De Palma's best films.[18] Scott wrote, "More than a quarter-century after Obsession, his feverish tribute to Vertigo, Mr. De Palma is still worshiping at the shrine of Hitchcock, as well as indulging in a good deal of auto-homage. Voyeurism, doubles, ambient paranoia -- the director's favorite motifs parade before us, along with winking allusions to Dressed to Kill, Body Double and Blow Out. Though it lacks the prickly, probing sense of human vulnerability that made those movies disturbing as well as exciting, Femme Fatale is far more absorbing and tantalizing than most of the plodding, overworked thrillers the studios churn out these days. Its brazenly illogical plot twists should embarrass lesser filmmakers who tout mechanical, uninteresting surprise endings."[16]

Ebert wrote, "Sly as a snake, Brian De Palma's Femme Fatale is a sexy thriller that coils back on itself in seductive deception. This is pure filmmaking, elegant and slippery. I haven't had as much fun second-guessing a movie since Mulholland Drive."[18]

At the 2002 Stinkers Bad Movie Awards, the film received nominations for Worst Director (De Palma) and Worst Actress (Romijn-Stamos, also for Rollerball). Romijn-Stamos ended up winning Worst Female Fake Accent for this film and Rollerball.[19]

Since then, Femme Fatale has been being revived in the eyes of many critics.[5] The film has since developed a cult status amongst cinephiles.[7][20][21][6]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Deming, Mark. "Femme Fatale (2002) – Brian De Palma". AllMovie. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ @Scream_Factory (28 February 2022). "***NEW OFFICIAL TITLE ANNOUNCEMENT***FEMME FATALE is on Blu-ray for the 1st time 5/17! Brian De Palma's stylish…" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Femme Fatale". Quad Cinema.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Femme Fatale". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- ^ a b "Director Brian de Palma's underrated gems, decade by decade". Los Angeles Times. 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b Koresky, Michael (17 July 2019). "Queer and Now and Then: 2002". Film Comment.

- ^ a b Sobczynski, Peter (23 August 2013). "Brian De Palma on "Passion," passion and film | Features". RogerEbert.com.

- ^ Sims, David (27 September 2019). "Antonio Banderas is One of the Best Movie Stars of His Generation". The Atlantic.

- ^ "Femme Fatale (2002)". WBShop.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2020.

- ^ "Femme Fatale - Blu-ray". Shout! Factory.

- ^ "Femme Fatale". The Numbers. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ "Femme Fatale". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ "Box Office Analysis: Nov. 10". hollywood.com. 10 November 2002. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Top Video Rentals for the week ending June 08, 2003". Video Store Magazine. Archived from the original on 9 December 2003. Retrieved 9 December 2003.

- ^ "Femme Fatale". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ a b Scott, A.O. (6 November 2002). "FILM REVIEW; Rooting for the Thieves at Cannes". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 August 2023.

- ^ "Femme Fatale". Metacritic.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (6 November 2002). "Femme Fatale". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ "Past Winners Database". The Envelope. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Body Double / Femme Fatale". American Cinematheque. Archived from the original on 22 November 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Femme Fatale". Museum of the Moving Image. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

External links[edit]

- 2002 films

- 2002 crime thriller films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s heist films

- 2000s mystery thriller films

- American crime thriller films

- American erotic thriller films

- American heist films

- American mystery thriller films

- American neo-noir films

- English-language French films

- English-language German films

- Films directed by Brian De Palma

- Films scored by Ryuichi Sakamoto

- Films set in Paris

- Films shot in Paris

- French crime thriller films

- French heist films

- French mystery thriller films

- French neo-noir films

- 2000s French-language films

- German crime thriller films

- German heist films

- German mystery thriller films

- German neo-noir films

- Warner Bros. films

- 2000s American films

- 2000s French films

- 2000s German films