Museums are no longer just places to see art – they’re venues to take selfies posted with #museum. So why not call out the elephant in the room? That’s the philosophy behind the Museum of Selfies, a pop-up exhibition which opens next month in Los Angeles.

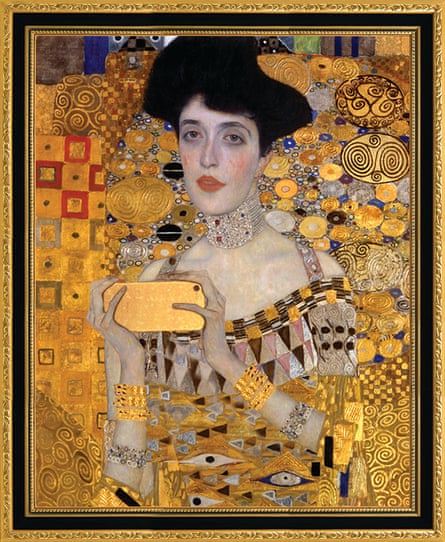

The exhibition traces the history of self-portraits from the prehistoric era to 2006, the year Paris Hilton claims to have “invented” the selfie. There are self-portraits in 21st-century art, mirror selfies by Jacqueline Kennedy in the 1960s, food selfies from Instagram, iconic skyscraper selfies and the infamous bathroom selfie. Naturally, there is an entire section devoted to “the art of the narcissist”.

The California game designers Tommy Honton and Tair Mamedov came up with the idea last year after learning that more people take selfies with Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in the Louvre in Paris than photograph the artwork itself.

“We joked around with the idea of a selfie museum and thought: ‘What about a space that explored something that was polarizing but undeniably catchy, in terms of selfie culture?’” asked Honton. “We bring in sceptics while exploring the history and the culture around this whole phenomenon.”

The 8,000 sq ft museum, which is set in a former department store, will be divided into two sections. The first is a timeline of the selfie from the first cave painting to Facebook and cellphone cameras. “We want to show people all these things had to converge for selfie culture to become a thing,” said Honton. “If we didn’t have social media, the selfie probably wouldn’t have taken off.”

The internet revolutionized the selfie, said Honton. “You can take a selfie with a Polaroid, but unless you can share it, or upload it quickly, what effect will it have?” he asks. “Selfies are universal – it’s culturally represented.”

The second part of the exhibition is a series of contemporary artists who have made artwork inspired by selfie culture, though their names are currently under wraps. The museum also hopes to announce something in the museum which will merit inclusion in the Guinness Book of World Records.

But while you might think a space like this is just another digitally driven exhibition, the museum has installations where people can make their own selfies. There are photo-op setups and a gym-like setting where guests can walk into a mirror showing six-pack abs or a “crazy pretzel” yoga pose. “It’s all sculpture. We wanted things to be physical, tactile and real,” said Honton.

More than just a theme park, though, the show aims to be educational. Did you know the first self-portrait photograph was taken in 1839 by the American lamp manufacturer Robert Cornelius? He had to stand still for 15 minutes to capture the daguerreotype image.

The term “selfie” was Oxford Dictionaries’ word of the year in 2013, but it was first used in 2002 in an online forum in Australia. Today, more than 2m selfies are uploaded daily.

But should we be worried by selfie culture? “We all have egos. Selfies aren’t bad unless they’re at the sake of your mental health, sanity or your life,” said Honton. That concern taps into an eerie section of the museum, which is devoted to death selfies. More than 300 people have died from selfie-related accidents, including drowning from taking selfies in water, falling on to railway tracks or tumbling off the tops of buildings.

“Why do people do this? Is it worth dying for a photo?” asks Honton. “We try and look at the psychology. We hope people will ask ‘why am I taking this photo?’ and ‘why do people do as they do?’”

There are no photos of the Kardashians in the exhibition, but they’re referenced as a default. “The fact that a famous person can pose for a photo with their phone in front of a mirror and have it be culturally relevant says a lot about our culture,” said Honton. “Their ‘just woke up’ selfies are mostly ads. It’s almost an art to make something look like its authentic when it’s staged.”

Ellen DeGeneres’ 2014 Oscar selfie, one of the most liked and shared images on Twitter, had a certain quality that made it successful – beyond its star-studded cast. “The strongest aspect people connect with in selfies is [their] unscripted, spontaneous approach,” said Honton. “That Oscar shot captured spontaneity and fun.”

The most-liked photos on Instagram are not selfies – Beyoncé’s twin pregnancy announcement last February garnered 11.2m likes, Selena Gomez’s kidney transplant in September got 10.5m likes, and the Portuguese soccer player Cristiano Ronaldo’s announcement of his fourth child’s birth is currently the most-liked photo on Instagram, with 11.29m likes.

The museum hopes to have its viewers question why we take and post photos in the first place. “Selfies are easy to document a trip, a moment, something to brag about,” said Honton. “It makes it easier to rely on a photo as a memory, but does a selfie make it more personal, or is it just to hoard them? People use it as a replacement for experiencing the real thing.”

Thankfully, the museum doesn’t take itself too seriously, however. “We don’t want this to be an elite, art world, ivory tower thing,” said Honton. “Art doesn’t have to be hard to understand – it can be for everyone.”