The Rise and Fall of Kah-Nee-Ta

Long an iconic destination beloved by generations of Oregonians, Kah-Nee-Ta Resort & Spa—where families from around the state came to swim, golf, and ride horses—is now on the list of the state’s ghost towns and desolate places. Behind a “no trespassing” sign, overgrown grass now completely obscures what used to be the golf course. Not a single soul or car can be seen for miles; only lone junipers stand sentinel here and there among the yellow flowering sagebrush.

“The closing of Kah-Nee-Ta and the earlier closing of the mill devastated the economy in the reservation,” a Tribal member, who asked to remain anonymous, told me pre-COVID at a local diner. With a glass case showing off slices of freshly made huckleberry pie, the restaurant is one of just a few food vendors serving a population of nearly 3,000. Still, business is slow; that afternoon, the restaurant was empty aside from our table. Another dining option is Reuse It Secondhand Store and Café, where you can eat a sandwich at a Formica booth surrounded by secondhand baby clothes and books, including a dog-eared copy of Barack Obama’s The Audacity of Hope. Bottles of used and yellowed nail polish are marked $0.99.

Other than these places, and the Indian Head Casino across Highway 26, a visitor to Warm Springs would be hard-pressed to find somewhere to go. On this writer’s visit, there were only a few locals walking about.

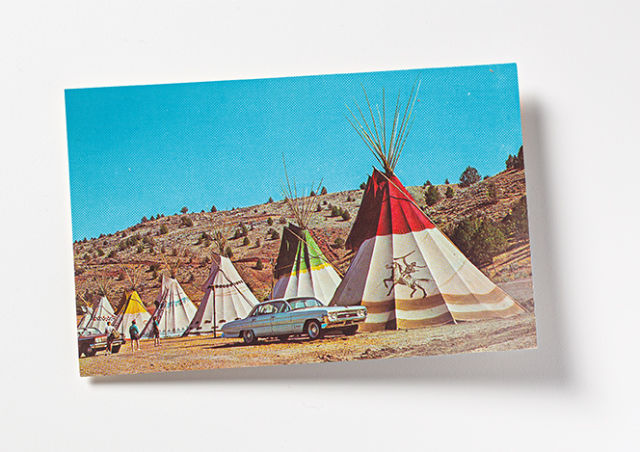

A postcard from the resort, promising “naturally heated warm water swimming pools of all mineral water of 85°” and “345 days of sunshine” a year.

Fortunes at Warm Springs Reservation had been declining for many years before Kah-Nee-Ta closed in September 2018, laying off 146 employees. But that was the start of a free fall, a dissolution of a community that is as wary of each other as of strangers, some residents say. Its crisis is little known in the outside world.

“It’s hard to keep straight when there is no hope here. Only thing that makes money is drugs,” says a Warm Springs resident who is married to a Tribal member. She estimated the unemployment rate to be “over 90 percent.” She counted herself among the lucky ones with some income: she does sewing and makes baked goods, her husband takes tourists around for trout fishing, and they take any other small jobs they can get. She declined to be identified for fear of reprisal in a culture of “crabs in a bucket” mentality. Neighbors turn on each other when anyone is seen as doing slightly better, she says. And speaking to a journalist about the reality of the reservation could draw retribution from the local powers that be.

As long as she could remain anonymous, she felt free to be candid: “This is a third world country in the middle of the US. We are the forgotten people here.”

James Edmund Greeley started working at Kah-Nee-Ta as a child in the resort’s early days in the ’70s. “My brother was an eagle dancer. My sisters were powwow dancers, and I was a little kid all dressed up in my dance attire, and we’d do entertainment for all the nonlocals down there.” Although he is a Tribal member, Greeley calls himself “independent” from the influence of the Tribal Council, as a self-employed Native American flutist.

Like many other Warm Springs residents, he attributes the closing of the resort to mismanagement. “I heard some people were being overpaid for their work.... Sometimes you get duplicate positions,” he told me when we met in his sprawling hilltop house a few miles from the shuttered resort last November.

Chris Smith says he witnessed the dysfunction firsthand while rising up Kah-Nee-Ta’s ladder, starting as a housekeeper in 1995 and and working up to a client services manager position, a job Smith held until the very last day. By the 2010s, the resort was a “very exhausted property with literally the same décor” for decades in the lobby and hotel rooms. But the antiquated facilities were only the outward sign of a deeper problem where professional management reported to a chain of command leading to the elected Tribal Council.

“It’s a small community, everyone’s related to everyone, and government officials are lifetime politicians. Oppressed people vote for who they know instead of who will reform,” Smith says. “There is a culture of oppression here.... Tribal politics is a different brand of politics.”

The Tribal Council tells a different story about Kah-Nee-Ta’s demise. Robert Brunoe, Warm Springs’ Tribal historic preservation officer and general manager of natural resources, acknowledged the resort closed due to “aging structures” and “complex issues.” But in Brunoe’s view outsiders are not entitled to point fingers. “When I hear from people who say they have fond memories of Kah-Nee-Ta and are sad that it’s closed, I think, ‘Maybe you should have just visited it more often,’” he told me with a smile when we met at his office. He declined to speak with me further without the Tribal Council’s approval, and did not answer a follow-up email.

Another postcard from the resort, promising “naturally heated warm water swimming pools of all mineral water of 85°” and “345 days of sunshine” a year.

In 2013, a new secretary-treasurer brought in to resuscitate the Tribal finances called out the absence of record-keeping and was eventually dismissed. By 2015, the financial situation became dire enough that a divided Tribal Council had to call on a federal inspector general to investigate the possible misuse of $100 million over 10 years.

But the story of Kah-Nee-Ta’s rise and fall reaches beyond the allegations of corruption and infighting. It goes back to the source—both literal and figurative—of the Warm Springs Reservation itself: its water.

The Warm Springs Reservation was born out of an 1855 treaty wherein the Wascos and the Warm Springs were forced to cede 10 million acres of fertile land around the Columbia River to the US government. In exchange, the Tribes were given $150,000 and 578,000 reserved acres in the high desert west of the Deschutes River, around 60 miles south of the Columbia. None of the Tribes were originally based in this area.

“The place you have mentioned, I have not seen. There is no Indians or whites there yet, and that is the reason I know nothing about that country,” said Mark, the then-chief of the Wascos. Much later, Owen M. Panner, a chief judge of the US District Court, testified that the Tribes “struggle[d] against almost hopeless odds” on a land that was “mountainous, rocky, had poor soil ... so that it was unlikely the white settlers would ever wish to occupy it.”

Boys fishing in a channel of Celilo Falls in 1956, before the dam closure.

As unjust as the 1855 treaty was, it entitled the tribes to use their “usual and accustomed” hunting, gathering, and fishing sites within the ceded territory. The most important of these was Celilo Falls, which was located where the Deschutes feeds into the mighty Columbia. With settlements and trading posts dating back 15,000 years, Celilo Falls was the oldest continuously inhabited site in North America. And that was just one of its many superlatives: the falls was the greatest fishing site on the continent, with an annual salmon run of up to 20 million, and the biggest waterfall by volume in North America.

But the extraordinary bounty of Celilo came to an abrupt end in 1957, when the US Army Corps of Engineers built The Dalles Dam just downstream. On March 10, hundreds of observers watched as the dam was locked, forever silencing the roaring cascades. In exchange for the loss of their ancestral fishing site, the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs received a $4.4 million compensation—around $40 million in 2020 dollars. In 1962, the Tribes used that settlement to build Kah-Nee-Ta around the hot springs on the Warm Springs River.

For a while, the investment appeared to be successful. By the late 1980s, Warm Springs Reservation had become one of America’s most prosperous sovereign nations, with “a stable of forest products industry, a luxury resort, a hydroelectric plant, and more jobs than people to fill them,” journalist Cynthia D. Stowell wrote glowingly in The Faces of a Reservation. “The Tribes have made the Celilo money work for them beyond anyone’s expectations.”

Now, the dilapidated remains of what the Tribe received seem decidedly unequal to what they gave up. “Four million dollars is cheap compared to the lifeblood of the First People. It’s nothing,” Greeley says. His father, who is of Warm Springs, Wasco, and Nez Perce ancestry, used to fish at Celilo before the flooding. Greeley has recorded a Native American flute song called “Celilo ‘Kup” to honor the legacy of the falls. (This was the first track in his album Before America, which won a Native American Music Award in 2017.) A faded photograph of pre-dam Celilo Falls hangs in his home.

More than 60 years after the flooding of Celilo, the sense of its loss remains strikingly palpable everywhere in the reservation. The same Celilo Falls photograph is fondly framed inside Warm Springs Market, the town’s only true grocery. The image of life-giving cascades creates a jarring juxtaposition against the store bulletin’s boil-water notices and a water-outage map highlighting large swaths of the reservation. Among the “third world” conditions that concern the residents, water insecurity ranks high: a pipe below Shitike Creek broke down in 2019, and many people went without running water all through the summer. Even when the water returned, there was risk of microbes in the pipes.

“We’ll take showers with it, wash our dishes with it. But consuming it is red flag for me,” Greeley says. “You go to Madras and you have spring water from the Metolius River coming out of the tap all day long. Fifty miles away we get bottom-of-the-barrel water.”

Most of the tap water in the reservation comes from the Deschutes River by way of Lake Billy Chinook, which in turn is fed by a number of tributaries. According to the Deschutes River Conservancy, agricultural runoffs including pesticides and animal waste are funneled into Lake Billy Chinook, resulting in toxic algae blooms and dangerous levels of E. coli. Central Oregon farms and ranches also use up 90 percent of the Deschutes River’s water withdrawals, at the expense of wildlife and human residents of the high desert. It’s a situation that all too clearly mirrors the displacement of hunter-gatherer Native peoples by white farmers during the age of the Oregon Trail—a process that has been ongoing for the past two hundred years.

Kah-Nee-Ta village more recently

Chris Watson, the executive director of the nonprofit Warm Springs Community Action Team, believes any discussion of the reservation’s economic difficulties would be misleading without addressing this legacy of displacement and institutional oppression. “I’m not saying the Tribal Council isn’t to blame, because policies could be created to encourage business. [But the economic problems here] are rooted in institutional barriers and the US government not fulfilling treaty responsibilities and creating a lot of red tape,” he says.

According to him, the most critical issue is that 98 percent of the reservation is federal trust land, as opposed to county land or fee land. Most Americans build wealth through buying a home, but because people on the reservation can’t build equity that way, they are excluded from getting loans from banks. “Tribal members can’t just buy land. In fact, they can’t own any land at all. Nobody actually owns the land on which their house rests,” Watson explains. “Throughout history, banks have not given loans to Natives, period. There are a million barriers for people in Warm Springs that don’t exist for people in Madras or other communities. It’s not that people don’t have an entrepreneurial spirit here.”

In that context, Kah-Nee-Ta’s failure isn’t due just to Tribal leaders’ oversight—but to deep-rooted structural issues that make Native self-sufficiency nearly impossible.

The pre-COVID unemployment rate in Warm Springs Reservation was 22.6 percent, according to 2018 Census Bureau figures (the most recent year for which data is available). But this number counts only those who are actively seeking jobs, not those who have given up on finding work in the near-complete absence of a job market. Meanwhile, 33.7 percent of the population falls under the poverty line; that number rises to roughly 50 percent for families with children under the age of 5. Sources told me some Warm Springs children go without regular meals on weekends.

[Editor’s note: We acknowledge that census data, for many communities of color, is notoriously unreliable. The unemployment figures are likely far higher than the government’s estimate, especially in the winter.]

After shuttering the lumber mill in 2016 (shedding 84 much-grieved jobs), the Tribal Council started looking for alternative sources of income. That same year, a cannabis business was authorized under its Warm Springs Ventures (WSV) arm, but it never started operating. According to a profit-and-loss statement obtained by Portland Monthly, Eagle Tech Systems, a drone training and certification business WSV touted as a modern growth opportunity, is set to post an annual loss of $9,300 in the next three years (2020–2022) under “Other Expenses”—with no other cost of goods, wages, operating expenses, or revenues listed.

And then there’s Native Fax, which a Tribal member described to me as “software that allows you to send faxes.” When I asked whether that need wasn’t already being fulfilled by Adobe PDF or a smartphone, he broke into resigned laughter. Another idea that came up was building a racetrack so “millionaires can show up with their toys.” This didn’t pass a council vote.

Not all ideas sound immediately destined for failure. In November 2019, Tribal Council considered a proposal for turning Kah-Nee-Ta into a hydrotherapy center combining medical-grade healing with natural beauty and outdoor activity. The idea was received favorably back then; unfortunately, the chances of realizing it appear slim in the aftermath of the coronavirus, at least for the near future.

The Dalles Dam today, with the remains of old shacks in the foreground.

The pandemic affected more than just the potential revival of Kah-Nee-Ta. During the quarantine, motor and electrical system failure, on top of the outstanding pipe breakage, left about 100 residents without any running water and about 2,000 under the (unfortunately chronic) boil-water notice. The Tribal Council, the Oregon Health Authority, and the federal government each contributed to distributing potable water, hand sanitizer, mobile showers, wash stations, and personal protection equipment; but the effort, while well-intentioned, was a too-little-too-late stop-gap measure against a deeply entrenched issue. The lack of access to clean water is surely a factor in yet another heart-wrenching number: With 2.8 percent of the residents testing positive in July, the reservation’s COVID infection rate per capita was higher than that of any Oregon county. And plagued by high unemployment and low economic activity since before the pandemic (when Oregon as a whole was posting record-low unemployment), Warm Springs will struggle more than other communities to overcome its impact. Meanwhile, Kah-Nee-Ta’s cerulean pools, once filled with mineral-rich, hot-spring water, are now completely dry.

That isn’t to say everything is bleak in Warm Springs. In July, Oregon’s legislative Emergency Board allocated $3.58 million of its federal Coronavirus Relief Fund for water infrastructure improvements at the reservation. This means a new pipe under Shitike Creek will be permanently installed by late 2020 or early 2021; and the residents reacted to the news with jubilation. Across political divides, there is a strong desire for Kah-Nee-Ta to reopen—and years after its closing, it’s still an attraction many Oregonians remember fondly. Meanwhile, Warm Springs Community Action Team is planning to open a small-business incubator by summer 2021, with coworking spaces, retail shops, an art gallery, and a coffee shop—right near Reuse It Secondhand Store and Café and across from a still-blinking sign pointing to Kah-Nee-Ta. Standing there, where a winding road to the resort splits off of Highway 26, one can’t help but appreciate the breathtaking beauty of this place. And even a visitor can see why Warm Springs locals feel a fierce attachment and pride despite the economic troubles, political strife, and social tensions. It’s true some of them stay only because they don’t have alternatives—but others choose to remain because they still have love and hope for this land.

Among Native Americans, the yearning for Celilo Falls is at least as great as that for Kah-Nee-Ta. Some, including Yakama Nation chairman JoDe Goudy, have called for Bonneville Dam, The Dalles Dam, and John Day Dam to be removed. Decommissioning dams is not unheard of in Oregon; the Sandy River’s Marmot Dam and Little Sandy Dam were removed in 2007 and 2008. This restored the migration routes of threatened anadromous fish—including coho salmon, steelhead trout, and chinook salmon—and allowed the Sandy to run free for the first time in more than a century.

The likelihood of that happening along the much-bigger Columbia River is minimal at best. But James Edmund Greeley still thinks it would be possible to unlock The Dalles Dam in honor of Celilo Falls. “We all know that Celilo Falls could have been one of the wonders of the world, like the Grand Canyon or Niagara Falls or Mount Rushmore,” he says. “Maybe for a week, no commerce. No barges up the Columbia River. You won’t die from pulling the plug on the dam for a week so that this generation can see Celilo Falls. So they can see and have a connection with what was there for 10,000 years.”