Nightmare Alley (1947 film)

| Nightmare Alley | |

|---|---|

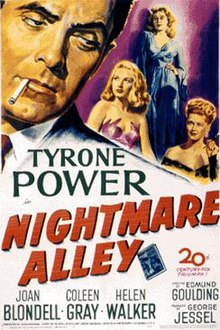

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Edmund Goulding |

| Screenplay by | Jules Furthman |

| Based on | Nightmare Alley by William Lindsay Gresham |

| Produced by | George Jessel |

| Starring | Tyrone Power Joan Blondell Coleen Gray Helen Walker |

| Cinematography | Lee Garmes |

| Edited by | Barbara McLean |

| Music by | Cyril J. Mockridge |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 111 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Nightmare Alley is a 1947 American film noir directed by Edmund Goulding from a screenplay by Jules Furthman.[2] Based on William Lindsay Gresham's 1946 novel of the same name, it stars Tyrone Power, with Joan Blondell, Coleen Gray, and Helen Walker in supporting roles. Power, wishing to expand beyond the romantic and swashbuckler roles that brought him to fame, requested 20th Century Fox's studio chief Darryl F. Zanuck to buy the rights to the novel so he could star as the unsavory lead[3] "The Great Stanton", a scheming carnival barker.

The film premiered in the United States on October 9, 1947, then went into wide release on October 28, 1947, later having six more European releases between November 1947 to May 1954.

As noted on the DVD commentary track by Alain Silver and James Ursini, Nightmare Alley was somewhat unusual among film noir in having top stars, production staff and a relatively large budget. The film was not a financial success upon its original release but has since found acclaim and is regarded as a classic.

Plot[edit]

A seedy traveling carnival's barker, Stanton "Stan" Carlisle, is fascinated by everything there, including a grotesque geek, who prompts an observation from Stanton that he "can't understand how anybody could get so low." Stanton works with "Mademoiselle Zeena" and her alcoholic husband, Pete. Once a top-billed vaudeville act, Zeena and Pete used an ingenious code to make it appear that she had extraordinary mental powers, until her attentions to other men drove Pete to drink and reduced them to working in carnivals. Stanton learns that many people want to buy the code from Zeena for a lot of money but she refuses to sell; she is saving it as a nest egg.

Stanton tries to romance Zeena into teaching it to him but she remains faithful to Pete, feeling guilty over the role she played in his downfall and effectively nursemaiding him in the hope of some day sending him to a detox clinic for alcoholics. But one night in Texas, Stanton accidentally gives Pete the wrong bottle: the old man dies from drinking wood alcohol instead of moonshine. To keep her act going, Zeena is forced to teach Stanton the mind-reading code so that he can serve as her assistant.

Stanton prefers the company of the younger Molly. When their romance is found out, the remainder of the carnies including strongman Bruno force the pair into a shotgun marriage. No longer welcome in the carnival, Stanton realizes this is actually a golden opportunity for him. He and his wife leave the carnival. He becomes "The Great Stanton," performing to enraptured audiences in expensive nightclubs in Chicago. As well as things seem to be going, however, Stanton remains emotionally troubled by Pete's death and by his own part in it. He eventually seeks counseling from psychologist Lilith Ritter, to whom he confesses all that has occurred.

Since Ritter makes a point of recording all of her sessions with her patients, she has accumulated sensitive information about various members of Chicago's social elite. Recognizing themselves as kindred spirits to a degree, she and Stanton conspire together to manipulate her patients, with Ritter secretly providing private information about them and Stanton using that information to convince them that he can communicate with the dead. The plan almost works, until Stanton tries to swindle skeptical Ezra Grindle by having Molly pose as the ghost of Grindle's long-lost love. When the heartbroken Grindle breaks down, Molly refuses to play out the charade and reveals her true self to Grindle, thereby exposing Stanton as a fake. As he prepares to flee, Stanton discovers he has been scammed by Ritter, who gives him only $150 of Grindle's money rather than the promised $150,000 they had conned him out of to that point. With her recordings of Stanton's confessions to her available for use against him, Ritter threatens to testify that he is mentally disturbed should he accuse her of complicity in his crimes. Defeated, Stanton gives the $150 to Molly and urges her return to the carnival world where people care for her. Meanwhile, he gradually sinks into alcoholism.

With nowhere else to go, Stanton tries to get a job at another carnival, only to suffer the ultimate degradation: the only job he can get is playing the geek, eating live chickens in a sideshow and replying to the offer with his recurring catchphrase, "Mister, I was made for it." Unable to stand his life any further, he goes berserk. However, Molly happens to work in the same carnival. She manages to calm him down and give him hope, bringing things full circle between Stanton and Molly, to Pete and Zeena's doomed relationship.

Cast[edit]

- Tyrone Power as Stanton "Stan" Carlisle

- Joan Blondell as Zeena Krumbein

- Coleen Gray as Molly Carlisle

- Helen Walker as Lilith Ritter

- Taylor Holmes as Ezra Grindle

- Mike Mazurki as Bruno

- Ian Keith as Pete Krumbein

Production[edit]

Tyrone Power, wishing to expand beyond the romantic and swashbuckler roles that brought him to fame, requested 20th Century Fox's studio chief Darryl F. Zanuck to buy the rights to the novel so he could star in it.[3] Fox paid $50,000 in September 1946 for the rights to Gresham's novel, and Gresham was hired as consultant to help screenwriter Jules Furthman, although the extent of his contribution to the script is not clear.[4]

In November 1946, it was reported that Mark Stevens and Anne Baxter were to star in the film, and that William Keighley would be the director. By January 1947, Lloyd Bacon was the reported director.[4]

To make the film more believable, the producers built a full working carnival on ten acres (40,000 m2) of the 20th Century Fox back lot. They also hired over 100 sideshow attractions and carnival people to add further authenticity. Filming also took place at the San Diego County Fair in Del Mar, California.[4]

The slightly upbeat but somewhat dark and ambiguous ending of the film was added by screenwriter Furthman at Zanuck's direction, softening the harsh ending of Gresham's novel for commercial purposes.[5] The novel's ending implies that Stanton is doomed to work as a geek until he drinks himself to death.

Author William Lindsay Gresham died by suicide by sleeping pills on September 14, 1962, in the same room in the Hotel Carter where he wrote the first draft of Nightmare Alley.[5]

Reception[edit]

On the film's original release, reviews were mixed, and the film was a box-office flop.[3]

The New York Times review commented,

If one can take any moral value out of Nightmare Alley it would seem to be that a terrible retribution is the inevitable consequence for he who would mockingly attempt to play God. Otherwise, the experience would not be very rewarding for, despite some fine and intense acting by Mr. Power and others, this film traverses distasteful dramatic ground and only rarely does it achieve any substance as entertainment.[6]

The Variety review complimented the film's acting, noting that:

Nightmare Alley is a harsh, brutal story told with the sharp clarity of an etching ... Most vivid of these is Joan Blondell as the girl he works for the secrets of the mind-reading act. Coleen Gray is sympathetic and convincing as his steadfast wife and partner in his act and Helen Walker comes through successfully as the calculating femme who topples Power from the heights of fortune back to degradation as the geek in the carney. Ian Keith is outstanding as Blondell's drunken husband.[7]

In Time magazine (November 24, 1947), film critic James Agee wrote:

"Nightmare Alley" would be unbearably brutal for general audiences if it were played for all the humour, cynicism and malign social observation that are implicit in it. It would be unbearably mawkish if it were played too solemnly. Scripter Jules Furthman and Director Edmund Goulding have steered a middle course, now and then crudely but on the whole with tact, skill and power. They have seldom forgotten that the original novel they were adapting is essentially intelligent trash, and they have never forgotten that on the screen pretty exciting things can be made of trash. From top to bottom of the cast, the playing is good. Joan Blondell, as the fading carnival queen, is excellent and Tyrone Power – who asked to be cast in the picture – steps into a new class as an actor".[8]

The film is now regarded as "one of the gems of film noir"[9] and as one of Power's finest performances. Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes retrospectively collected 64 reviews and gave the film an 88% approval rating, with an average rating of 7.7/10. The consensus summarizes: "Playing against type with Nightmare Alley, Tyrone Power and Edmund Goulding deliver some of their best work in a carnival-set noir unafraid to showcase true despair."[10]

2021 adaptation[edit]

On December 12, 2017, Fox Searchlight Pictures announced that Guillermo del Toro would be directing a new adaptation of the novel, co-writing the screenplay with Kim Morgan.[11] In April 2019, Leonardo DiCaprio was negotiating to star in del Toro's film.[12] In August 2019, it was reported that Cate Blanchett was negotiating to co-star with Bradley Cooper in the film.[13] On September 4, 2019, Rooney Mara was cast in the film. Filming commenced in January 2020 and production wrapped in December 2020. The film was released on December 17, 2021.[14]

References[edit]

- ^ "Nightmare Alley – Original Print Information". Turner Classic Movies Database.

- ^ Crump, Andy (August 9, 2015). "The 100 Best Film Noirs of All Time". Paste. Archived from the original on August 12, 2015. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c Muller, Eddie (May 5, 2019). Turner Classic Movie. Event occurs at the Intro to the presentation of the film.

- ^ a b c Nightmare Alley at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ^ a b Muller, Eddie (May 5, 2019). Turner Classic Movie. Event occurs at the Outro to the presentation of the film.

- ^ Pryor, Thomas M. (October 10, 1947). "Nightmare Alley", The New York Times, film review. Retrieved March 11, 2008.

- ^ Fisk (October 15, 1947). "Nightmare Alley", Variety, film review. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ Agee, James (2000) [November 24, 1947]. "Agee on Film: Criticism and Comment on the Movies". Time. New York: Modern Library. p. 369.

- ^ Zacharek, Stephanie. "Nightmare Alley (1947)". Turner Classic Movies Database. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ Nightmare Alley at Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (December 12, 2017). "Guillermo del Toro Taps Scott Cooper for 'Antlers' and Sets New Project 'Nightmare Alley' (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (April 23, 2019). "Leonardo DiCaprio in Talks to Star in Guillermo del Toro's 'Nightmare Alley' (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (August 2, 2019). "Cate Blanchett Eyes Guillermo del Toro's 'Nightmare Alley' With Bradley Cooper (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ Searchlight Pictures [@searchlightpics] (September 10, 2021). "Nightmare Alley. A Guillermo del Toro Film. In Theaters Everywhere. December 17. @RealGDT" (Tweet). Retrieved September 10, 2021 – via Twitter.

Further reading[edit]

- Hoberman, J. (January 25, 2000). "Side Shows". The Village Voice.

External links[edit]

- Nightmare Alley at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Nightmare Alley at IMDb

- Nightmare Alley at AllMovie

- Nightmare Alley at the TCM Movie Database

- Nightmare Alley is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- Nightmare Alley: The Fool Who Walks in Motley . . . an essay by Kim Morgan at the Criterion Collection

- 1947 films

- 1947 crime drama films

- 1940s English-language films

- 20th Century Fox films

- American black-and-white films

- American crime drama films

- Circus films

- Film noir

- Films about magic and magicians

- Films about sideshow performers

- Films based on American novels

- Films directed by Edmund Goulding

- Films scored by Cyril J. Mockridge

- Films set in Chicago

- Films with screenplays by Jules Furthman

- 1940s American films

- Films about alcoholism