A rare 17th century folding screen that is officially classified a national treasure of Mexico is being offered at an online-only auction by Sotheby’s with an estimated price of $3-5 million. Bidding is open through October 11th. The starting bid is $2,800,000. No bidders yet. As a national treasure the screen cannot leave Mexico, so whoever buys it is going to have to be local or willing to lend it to a local institution indefinitely.

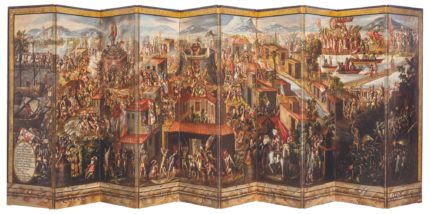

The screen is more than six feet high and 18 feet long, composed of 10 joined panels on a wooden frame. It is double-sided. On one side is a violently active depiction of the conquest of Tenochtitlán. Key events are shown in the locations where they took place as if they had occurred in the same moment and are numbered for identification with a key in the bottom left. Cortés’ arrival is in the upper right corner. Moctezuma II, the last Mexica emperor, is on the fourth panel from the left on a balcony as his assassins below aim fatal arrows at him.

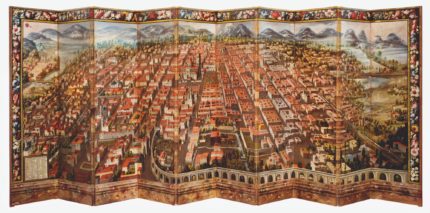

In a deliberately stark contrast, the other side features an overhead map of the new Mexico City, the capital of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, a grid of clean, airy streets lined with stucco buildings with red-tiled roofs, churches, schools, hospitals, public squares, a Roman-like arched aqueduct in the foreground, mountains and lake in the background. Devoid of people, this is the idealized vision of colonial Mexico. All the fire, feathers and fighting replaced with the calm cleanliness of European civilization.

Entitled Biombo de la Conquista de Mexico y Vista de la Ciudad de Mexico, it was painted by an unknown artist in the second half of the 17th century. The fall of Tenochtitlán was based on the account in the True History of the Conquest of New Spain, a popular memoir of the conquest of Mexico written by Bernal Díaz del Castillo, one of Hernán Cortés’ soldiers. The view of the colonial city was inspired by early 17th century decorative maps like the 1628 map of Mexico City by Juan Gómez de Trasmonte, now lost and known only from replicas.

The word “biombo” is a Hispanicized version of the Japanese “byobu,” literally meaning “protection from wind.” Byobu were luxury goods, first introduced to Japan from China in the 8th century, and imported into New Spain via the Manila Galleons that, in exchange for Mexican silver, transported Asian spices, silks, porcelain and other luxury goods from modern-day Cebu in the Philippines to Acapulco and many, many points in between. The trade between America and Asia had an enormous influence on Mexican decorative arts during the Viceroyalty period. Biombos took the Japanese form and replaced the pastoral landscapes, people and animals with narratives and urban locations that resonated strongly with the criollos (Mexican-born Spaniards) of the ruling class who commissioned them.

It is unquestionably of museum quality. The Museo Franz Mayer and the Museo Nacional de Historia in Mexico City each have biombos of their own on the same theme. This is the finest and largest example still in private hands.

![The Banquet Scene, 645-635 B.C., Assyrian, Gypsum, H: 58.42 cm x W: 139.7 cm x D: 15.24 cm, British Museum [1856,0909.53] [1856], Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.](http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/The-Banquet-Scene-430x184.jpg)

![The Garden of Ashurbanipal, 645 - 635 B.C., Assyrian, Gypsum, H: 168.5 × W: 51 × D: 13 cm (66 5/16 × 20 1/16 × 5 1/8 in.), British Museum [1856, 0909.56] [1856], Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.](http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/The-Garden-of-Ashurbanipal-65x150.jpg)

![Attack on an Enemy Town, 730 - 727 B.C., Assyrian, Gypsum, Object: H: 98 × W: 211 × D: 12.7 cm (38 9/16 × 83 1/16 × 5 in.), Object (left side): H: 91 cm (35 13/16 in.), British Museum [1880,0130.7 and 1848,1104.4] [1880;1848], Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.](http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Attack-on-an-enemy-town-200x120.jpg)

![Camel Rider, 728 B.C., Assyrian, Gypsum, H: 119.4 × W: 174.6 × D: 13.7 cm (47 × 68 3/4 × 5 3/8 in.), British Museum [1849,1222.11] [1849], Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.](http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Camel-rider-200x147.jpg)

![Royal Lion Hunt, 875 - 860 B.C., Assyrian, Gypsum, Object: H: 95.8 × W: 137.2 × D: 20.3 cm (37 11/16 × 54 × 8 in.), British Museum [1849,1222.8] [1849], Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.](http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Royal-lion-hunt-200x149.jpg)

![Celebration after a Bull Hunt, 875 - 860 B.C., Assyrian, Gypsum, Object: H: 101.6 × W: 223.5 × D: 13.3 cm (40 × 88 × 5 1/4 in.), British Museum [1849,1222.18] [1849], Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.](http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Celebration-after-bull-hunt-200x114.jpg)

![Head of a Bearded Man, 710 - 705 B.C., Assyrian, Gypsum, H: 62.2 × W: 55.2 × D: 16 cm (24 1/2 × 21 3/4 × 6 5/16 in.), British Museum [1847,0702.11] [1847], Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.](http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Head-of-a-bearded-man-200x205.jpg)