Bonnie Bramlett: Bobby Whitlock, man, he's in England with Eric.

That exchange happened in 1970 when Rolling Stone reporter David Dalton was shadowing Joplin on the Festival Express, a train tour across Canada. Delaney & Bonnie were on the bill, but without the services of Bobby Whitlock, who had joined Eric Clapton in Derek and the Dominos.

Whitlock wrote or co-wrote seven tracks on their masterpiece, Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs. After a tour and a half-hearted follow-up album, the group disbanded; Bobby released four solo albums, then went on an extended hiatus in 1976.

His musical resurgence began in 1999 with his album It's About Time. Soon after, he took up with Coco Carmel, and the two were soon making music together.

Coco was married to Delaney Bramlett in the '90s and co-produced his album Sounds From Home. A musical polymath, she excels on sax and is a formidable songwriter - skills she puts to use on her collaborations with Bobby.

We spoke with Bobby and Coco about their musical journey, their longevity as a couple, and a good deed courtesy of Mr. Clapton.

Carl Wiser (Songfacts): Coco, I would like to hear from you first on this one. Passionate love as evidenced in the song "Layla" has a way of flaming out over time. You guys, however, have somehow managed to thrive in this crazy crucible. How did you do it?

Carl Wiser (Songfacts): Coco, I would like to hear from you first on this one. Passionate love as evidenced in the song "Layla" has a way of flaming out over time. You guys, however, have somehow managed to thrive in this crazy crucible. How did you do it?Coco Carmel: Probably because Bobby and I have both been through so much. We've just both gotten to the great place in our lives where we like the same kind of thing and we don't put up with the same old things that we used to.

Our relationship is a real giving one. He gives a lot, and I hope that I do, so it's kind of a mutual thing. And everything that we do, we do together. Everything that we do, we share with each other. So there's no "This is yours, that's mine," "This belongs to me, this is yours," "Let's have a prenuptial agreement" or anything like that. Our whole world, we just share everything with each other. So I think that's how we've managed to survive all those things that can happen to people. Especially in musical relationships that don't seem to last very long.

Songfacts: What do you think, Bobby?

Bobby Whitlock: Well, we came into our relationship not to start singing and playing. We didn't even mean to get together. We were literally strangers. We had only seen each other for a moment. And by both of our respective ex-families, Coco and I were pushed together. We became friends and lovers and we were engaged for five years before we got married. Everyone thought we ran off.

We just started out trying to help each other and hold each other up through such a traumatic time, because we both lost everything in our respective past lives, everything and everyone. And so all we really had was us. Just us. That's why we're calling our tour this time, Just Us.

But that's what it is still, just Coco and me. We're close friends, first. We were friends before we ever even held hands.

Songfacts: When you say you lost everything, are you referring not only to the family lives that you lost before, but also financially?

Bobby: Well, yes. That, and I divested myself of my own income that I had from royalties and things like that to help us get a new start. My ex-family members and ex-friends, it seemed that all they were interested in was what money I had. And I decided just to go ahead and get rid of it and the root of it to see what would happen then. And, of course, we didn't hear anything from anybody after that, because they had no reason to call me anymore or come around wanting anything from me anymore. And what it did, it just left room for us to start all over again.

And I had no problem with it, starting all over again. What I had done in my past wasn't the end of it all for me, because I've been writing songs as long as I can recall. And we've got new material, there's been new stuff since then. So if I had just sat around resting on my laurels, I would have a calloused sitting place, you know?

Songfacts: Yeah. I get that you want to move forward. But, Bobby, does this mean that you gave up your royalties to say, the Layla album?

Bobby: I did. I got rid of everything. And when Coco and I started, we would go play and we didn't know if we were going to have gas money to get back. We were in Alabama. We said, Let's just go play, this is the only thing we can do. Let's you and me just go out with our guitars and sing and play.

And of course, the money soon runs out. What we didn't spend for ourselves, we gave away. We helped some other folks to get by in their world and get their feet back on the ground.

And as fate would have it and as it happens in Bobby time, I got a phone call from Eric Clapton's manager, Michael Eaton, and he told me that he's also his attorney. He says, "Sit down, I want to talk to you for a minute."

Anytime somebody tells me on the phone, "Sit down," I'm figuring it's going to be pretty heavy duty.

What happened was, just before the 40th anniversary of Layla came out, Eric asked as they were packaging everything, "What's Bobby going to get out of this?" And Michael told him, "Nothing, because he sold all of his royalties. He sold all of his vested interest in it." Well, unbeknownst to me, Eric and Michael took their attorneys in to the respective Warner/Chappel and Universal and all the other companies and bought back my rights to my income and restored them and gave them back to me. Out of the blue.

Songfacts: Wow.

Coco: Which doesn't ever happen in this business.

And I said, Yeah, well, it was that and this girl in France that Eric was seeing for a little while while we were there. I'd forgotten about Pattie [Boyd - subject of "Layla"] asking him about those pants. But anyway, before I would answer this and put it out publicly online, I decided, Well, I probably ought to write Eric.

I had his e-mail address, but I'd never written him. I never asked for anything. You know, I don't want anything from anybody, especially him. I wrote to him and said, "I just want to clear this up, in case you've forgotten, this is how it came." I said, "You came to me at Hurtwood [Clapton's house in England where the band would rehearse], I was standing in the doorway of the TV room and you walked up to me and you said, 'What do you think of this?'"

He was holding the guitar and he sang me the first two verses, all except for the last line on the second verse. And I said, "You won't find a better loser."

And then we went into the TV room and wrote the chorus, the bridge: "Do you want to see me crawl across the floor to you? Do you want to hear me beg you to take me back? I'd gladly do it." And then Eric comes in: "I don't want to fade away, give me one more day." And then the last verse, he wrote three quarters of it, and I came in with the very last line. I said, "That's how it goes. I hope this helps refresh your memory." And that was the end of it.

Well, within three minutes he wrote back, "He's right, he's absolutely right." He was writing to Michael, saying, "Yeah, I've been thinking about this."

Well, they have gone to all of the PR reps, ASCAP, BMI, all of the people, Universal, all the folks that changed it around. So from now on forever, "Bell Bottom Blues" is going to read "Written by Eric Clapton and Bobby Whitlock."

Songfacts: Fantastic.

Bobby: Yeah. That's just how things happen in our world.

Songfacts: It's interesting how you were talking about the times when you, not too long ago, were looking for gas money, going out, playing. Those are the times that musicians fondly remember even after they've become rich and famous, and spend so much time trying to get back to.

Coco: That's true.

Bobby: Yeah, but I tell you, it's not hard to get back there.

Coco: I'm not so sure that they really want to get back there. [Laughing]

Bobby: Playing in a small club, taking your own equipment in is a humbling experience, and it puts you in the right place. It puts you in the right place to present what you're presenting to the public. It's kind of like a relationship like Coco and me: It's not mine and yours or yours and mine, it's ours. So when someone comes to one of our shows, that is We. It's a We situation. They're included in it. They'd see us drive up with our equipment, and it's not a lot of equipment - four guitars, saxophone, a little piano and two amps - but it's Coco and me bringing it in. We don't have an entourage. We don't have roadies. We don't have management. We bring it in, we set it up in front of you and turn around and say, "Okay, now it's time." And the set begins.

Everyone feels a part of it. So we're not so far removed from our listening public that we can't reach out and touch them.

Songfacts: Coco, you've got over 100 songs to your credit that you've written. Can you tell me about how you go about writing a song and where you find inspiration?

Coco: Well, usually the inspiration comes from within me. I don't sit around trying to write a song. I quit doing that after I left Delaney, because there was a lot of "Let's try to write a song" going on. He was getting involved with some people in Nashville, so on and off he would do that.

So my inspiration, I wait for that to come to me. I don't sit around trying to write songs so much - I just find that the ones I allow to happen turn out to be my better songs.

Consequently, I think I'm becoming a better songwriter the more I do this, the more years go by.

Now, what was the first part of that question again?

Songfacts: The other part was more logistical, how you go about writing a song.

Coco: Oh, yeah, how do I go about it? Well, that varies. When Bobby and I are writing songs, I usually come to him with a pretty good amount of something, because he tends to write so quickly that I can't keep up with him.

When I write a song by myself, I have time to think about it. There's no banter, there's no going back and forth with anyone, so I can sit privately in a room and things will come to me. Sometimes they come so quickly I can't even write it down fast enough. Those are the songs like "Nobody Knows." It just happened. I don't even remember writing it. It's one of those songs that just came through me so fast, and it's my best song. It's a song that we do every time we play, it's on a couple of our records.

So some of them come very quickly, and I don't remember writing them. Like "Devil Blues," I had an idea, talked to Bobby about it for a second, and he started playing it. Next thing I knew we had a full-blown song, and it's another one of my favorite songs.

So it can happen in so many different ways. There's never one set way of writing a song for me. It's always different.

Songfacts: I'm intrigued by "Nobody Knows," because it seems to be about how you don't know what's going to happen after you die. It's an interesting thought.

Coco: The song does come from the idea that you don't know what's happening after you leave here. To me, there's no death. That is my own belief and I'm sure that there are a lot of people who believe that, too. I don't believe that there's an end to life.

Songfacts: You guys both cover some fairly spiritual songs. "John The Revelator" is another one. Can you talk about why you were drawn to that song and songs with that type of theme?

Bobby: I'm religious about being nonreligious. That's the only religion I have is none. I'm a son of a Southern Baptist minister, too. So I know what it isn't, that's for sure.

Coco came to me one time because I never do material that's not mine.

Coco: What doesn't directly relate to you for some reason.

Bobby: Except for "Layla." It came to me to do both versions in one: slow and fast. Do it like where it originally came from.

But one time Coco said, "This is a good song. I think this would be a good song for you." And she says, "John the Revelator." I'd never heard it. So I went online and I saw a guitar player, his name is Warren Haynes, and he played with the Allman Brothers for a while, and Gov't Mule. I just looked up "John the Revelator" and it was the first one I saw.

He started singing it, and then here come some tuba players on stage, so I immediately turned it off because rock n' roll and tubas don't mix. Soul music and tubas don't mix. Gospel music and tubas don't mix. So there was nothing there I wanted to see or hear.

So I clicked it off and I got the original. It was by Willie Jefferson, and he was also a Southern Baptist minister's son. But his daddy blinded him, put acid in his eyes when he was six and blinded him. Well, I couldn't make sense of what he was singing, so it didn't make any sense to me. I couldn't wrap my head around what I didn't know, so I looked up another somebody whose name is Son House, and he had a version of it. Seems that everybody has a version of "John the Revelator," and there are about five or six different people claiming songwriters on it.

I said the heck with it, I'm just going to write my own. And that's what I did. There's a verse in the original that says, "God walked out in the Garden of Eden." Now, if there is or was such a thing as God, it would be the Garden itself, it wouldn't be walking out into the Garden and calling Adam by his name.

I just said, "God called out in the Garden of Eden, Adam by his name, but he refused to answer because he was naked and ashamed." It just all started falling out.

Coco: I sat there and watched him just pen this thing out. I mean, it took him maybe 15 minutes to a half an hour to do it. And then he went back and just fixed a couple of little things. Bobby writes so quickly, it's very hard to keep up with him.

Bobby: For me it's in the flow of opening myself up for that creative influence of principle of the universe to operate, and it can't operate if you don't open yourself to it. Keith Richards says he's an antenna, and I understand that.

Coco: Willie Nelson says the same thing.

Bobby: Yeah. You've got to open up and let that creative principle operate through you. And when you do, it operates for you and as you. And when that happens, it's like picking apples fresh off the tree. The first thing that flows out, 99 percent of the time, that's what it is. That's the word. That is the one. That's the reality of it, is what comes out naturally. Your first instinct, the very first thing.

Now, you'll go on and try to refine it and do this to it and do that, sometimes you get lost and away from the original. Always, always, always you wind up going back to the original version, your original lines. Like when you get to a T-junction in the road, your instinct tells you to turn left, but no, I'm going to take a right. You get about three or four miles down the road and say, Man, I should have turned left. And you go back the way naturally you would have gone anyway, just listening to that gut instinct.

There's no difference in losing your keys and trying to figure out that line in the song. You just have to back off of it, next thing you know you find your keys and the line in the song.

Coco: Or sometimes it'll just pour out so fast you don't even remember writing it.

Bobby: Can't even put it down. Can't get it down right, it's just flowing.

Songfacts: What was it like writing "Devil Blues" together, composing a song that is about heartbreak and torment?

Coco: Well, the idea came to me and then I went to Bobby and it just started to flow. It was so good you couldn't stop it. So it was just very simple. I mean, writing with Bobby is really, really easy.

Bobby: It just happens itself. Everything has a flow: The rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain. It all has a flow to it, and it just seems to come out when the switches get flipped inside my conscious awareness and the melody comes to go with the words.

Bobby: And some of them are from there. There's a song called "Lonesome" that I've never even written down. As a matter of fact, "Thorn Tree in the Garden," I've never even written the lyrics out. Sometimes they're just not necessary. If it's right, it'll stay with you. You don't have to have a pen and paper.

Coco: I don't know. I think Bobby's probably one of the very few people that can do that. That's not the case for me. I have to write it down.

Bobby: Eric and I, our songwriting started going south, and I don't mean that literally like southern America. I mean, the well had run dry. The inspirational well had run dry with Eric and me. And one of the very last things that we ever did together, he said to me... it seems to always happen in doorways. This is in the doorway of his living room. He came to me and he says, "What do you think of this, man?" And he started playing it. And first he said, "Do you know who Veronica Lake is?" And I went, "No." He said, "Well, she's a actress, she didn't say very much, she didn't move her mouth." I said, "I know who you're talking about. She looked down a lot and she didn't move her mouth when she talked."

He started playing. He went [singing] "Dear Veronica, someone somewhere still loves you. Someone somewhere still cares."

It was so Eric. And that was it. We never did any more to it. I couldn't figure out the chord changes. But I carried around this unfinished symphony forever. And then about 10 years ago when we were in Nashville, I was talking to Coco about this very same thing. I would always try to play it on guitar. Well, I sat down at the piano and was talking about it, and it just fell out, the whole dang song, the rest of it. All but Eric's first verse. It all just fell out, just as I was sitting there. I was the vessel through which it poured.

And that song's on one of our records, as well. [The song is called "Dear Veronica."]

Songfacts: Bobby, I went back and read a review of a Dominos show, and it explained that Eric Clapton used the songs as a vehicle for his solos, and this review is saying it was too much Eric and the backing band didn't get their due. What was your take on that?

Bobby: I think whoever wrote that probably was thinking more of themselves and trying to sound like they know something that they don't. [This particular review was written by Jon Tiven for a fanzine called New Haven Rock Press. Jon was probably 16 years old at the time, so we'll cut him some slack.]

The band got everything that was due. We were all equals in Derek and the Dominos. We shared everything equally, and that includes singing. Nobody ever told anybody what to play - Eric never told me what to sing. It was wide open for me to sing anytime and anything I wanted to. It's the same with me and Coco. I've never told her one thing to sing. She knows what to sing and what not to sing.

It was all about Eric Clapton? Yeah! Well, hell, it was a rock and roll band, and he was a guitar player, and when it came time for a solo, we're not going to give it to Carl [Radle, bass player]. [Laughing] And I didn't take solos. I was just getting used to playing piano. I'd never played piano until we did All Things Must Pass.

For the story of these sessions (fun with Phil Spector!) and details on the Layla sessions, check out our 2004 interview with Bobby.

Bobby: And so don't be handing me no solo. I don't want to play a solo. That's what lead guitars are for.

Coco: And saxophones. [Laughs]

Bobby: Jim Gordon was going on about how he never got a drum solo, so we fixed his little wagon. We gave him a drum solo in "Let It Rain" and it lasted for nine-and-a-half minutes.

And he kept going - you could hear it in the solo. He would stop and he was looking at Eric. We were on the side of the stage behind the curtain smoking a cigarette and having a drink, and we wouldn't come back out. So he had to keep going and keep going. Okay, Mr. Drummerman, you want a solo? Take your solo.

And it worked. We did it together after that.

Songfacts: Bobby, that keyboard sound you came up with, what was it about that time that allowed you to create these sounds that nobody could touch?

Bobby: Well, nobody can follow you on a Hammond B3 and duplicate what you had done or replicate it, because my Hammond playing - my keyboard playing - I never play it the same way twice. There's no way I can.

Coco: But you always play it with the same kind of thing. It's a Bobby thing. I mean, he becomes the instrument. I've never seen anything like it.

Bobby: It just flows through me. The Hammond organ, it's got all these drawbars, and it goes from low to high, so as a song goes along, it rises and falls. It has an ebb and flow to it. And the drawbars on the Hammond color that song, they give it dimension. The lows through the highs. And as the song moves, as it swells and then comes back down, I'm working the drawbars, as the song dictates what it needs.

So it's not punching buttons. These drawbars you move with your hand in and out, so I just grab a whole handful of them and move it until it's just right. This happens in the middle of everything while the song is going down, so I can't go back and do it the same way twice. It's never the same twice.

And I think that's a good thing: for a song not to be done exactly the same way. Because it gets old real, real quick. The way I do things, it's always new. If you ask somebody to go back and paint another picture just like the one they just painted, they can't do it. It might get close, but they'll never get it just right. And the first one is always their favorite.

Songfacts: Coco, that's kind of interesting hearing Bobby talk about how he makes the keyboard come to life and what makes it special. What's your take on the saxophone?

Coco: Well, I never really listened to a lot of saxophone players, and I did that on purpose. I had a couple of people that I did listen to, Louis Jordan and Earl Bostic early on when I was first starting out. But mainly I stayed away from that, because I didn't want to fall into the same trap of playing all the same kind of stuff that all the saxophone players play. So I just don't do that. And they can all have that. I think they're incredible, these horn players that I hear, they're phenomenal. Their fingers are like lightning. I don't know how they do it.

Mine is more feel. And again, it's just something that I feel from within. I like to play kind of freestyle, and I've always done that. There are certain things that I do play that are important, some of the licks on "Layla," some of the things on "Devil Blues," the opening with the horn. So it's the same thing every single time on something like that.

But in between that, I just like to play. If I feel something happening, it's like a guitar player, you want to put something there, but try not to overdo it.

And I do have my own sound and that's just developed throughout the years of playing. That's pretty much it.

Bobby: Well, Coco's playing is very much like Eric Clapton's guitar playing in that he sings with his guitar. He sings, uses it as a voice. He told me this himself. This is when he couldn't sing, when he wasn't singing. Eric can sing, but he's not a born singer.

Coco: Just like me. I'm not a born singer. [Laughing]

Bobby: He's a born guitar player. He has come into his own, as has Coco come into her own. But she finds her place with me like I found my place with him. But his playing is like singing a melodic line without words, and Coco's saxophone is the same way.

Bobby: He's a born guitar player. He has come into his own, as has Coco come into her own. But she finds her place with me like I found my place with him. But his playing is like singing a melodic line without words, and Coco's saxophone is the same way. To me, Coco plays an awful lot like King Curtis. He was one of the finer players, and he was sensitive to playing with the guitar, as is Coco.

Coco: That is one thing that Delaney would say. He thought that my playing was very similar to King Curtis. I just don't see that. But that's nothing to be ashamed of.

Bobby: No, and she's a great bass player. No one knows about it, but she's a great bass player. She played bass on every one of our CDs, and a lot of things she and Delaney did together, as well. She's right in there with Carl and Duck [Dunn] and everybody else. But she doesn't ever say anything about it.

Coco: No, because I don't play it enough for me to even say such a thing.

Bobby: Playing on all of our records is enough. There's like nine CDs we've got out and she played bass on every one of them. One time we were shy a bass player on our gig. He couldn't make it, so Coco did it. The drummer stood up in the middle of the show and applauded her. Brannen Temple's our guy that we use and he's no slouch drummer, that's for sure.

One thing about Austin, Texas, it's full of great musicians. All of them out of work, but still good musicians.

Songfacts: Coco, when were you married to Delaney Bramlett?

Coco: Let's see, I met Delaney in 1987 and we were together not long after that. So we were together for 13 years.

Songfacts: Bobby, you had the good fortune of growing up in Memphis right near Stax. The folks I've talked to that were part of that said they were free to experiment, you could do whatever you wanted in those early times. What did you see when you were there?

Bobby: Exactly that. I saw all this stuff coming together. Everything was new. Stax is an old movie theater, and the main floor went down like a movie theater's does. If you put a marble on it, it'd roll to the door.

Then up at the top it was the glass, where the control room is behind the glass. They had headsets, but they didn't use them. Al Jackson used a headset just to communicate back and forth with Ronnie Capone, engineer. But they played it live and raw.

And there was a two-track. It went through four channels of the board, and it had big, black RCA knobs. And I watched Steve Cropper fade a crosscut saw, and he laid his left arm across the top of those four big knobs and went to the left. That's how they faded all four. Then in the corner they had a two-track machine, and then that went straight to a presser, which would do the acetate.

Those songs were written in one room. Hayes and Porter [Isaac Hayes and David Porter] or Bettye Crutcher and Homer Banks would write something in one room at Stax. It would be brought out to the studio for Duck and Al and Booker and Steve. They would put it down and it would be recorded. And then they'd make the press copy, the acetate, what they were using in the pressing plant, to make everything right there.

And while this was going down, there was a brand new eight-track recording machine that sat in the corner for over a year, because they were so used to it being the way it was and having that raw sound. Now everyone is spending millions of dollars trying to use high-tech equipment.

Coco: And trying to sound like that.

Bobby: Trying to sound like old two-track.

So I watched it all go down. It was an interesting thing. Everybody was experimenting. Everyone was doing whatever they felt like doing. There was a time when black and white artists playing together, white guys playing rhythm and blues, it was unheard of. But there they were, doing it and laying it down.

Songfacts: Did you end up on any sessions?

Bobby: The first thing I ever did... well the first time except for when I was 12 and Bill Black recorded me singing the Lord's Prayer at his Sonic Studios. And that was for Ted Mack Amateur Hour. I won a 6-pack of chicken legs and a Brownie Instamatic. We had fried chicken that night and took pictures of it.

But the first thing I recorded at Stax was a song by Sam & Dave. Isaac Hayes, David Porter and I are doing hand claps on it. [Singing] "Didn't have to treat me like you did, but you did, but you did, and I thank you." Clap clap clap clap. And we're clapping hands, like, clap clap clap clap.

Those days they would do hand claps and mix it down in with the drums, so it really just gave the drums that much extra.

Coco: Yeah, all the drums were always mixed down together. It would open up your other tracks, if you're doing eight tracks. Kind of like the Dominos did on their thing.

Songfacts: That's pretty fortunate that of all the tracks that you could have ended up on, it ended up being this classic song.

Bobby: It's fortunate. It's pretty amazing.

Coco: The thing is, they all saw Bobby's extreme talent as a child. I mean, his whole thing goes way back to when he was a little kid and they wanted to take him to Nashville. They said, "You need to get this kid to Nashville."

Bobby: Dewey Phillips said that. He was a famous DJ. He's the one that had the Red Hot & Blue show, and pretty much broke Elvis Presley into the singing. He played I think "That's Alright Mama" for 48 hours straight on WHBQ, which he was on then. WDIA was the black station in town, and B.B. King was the DJ at WDIA. And a lot of people didn't know that B.B. started out as a disc jockey.

Songfacts: Coco makes a good point about having talented people around you when you're making music.

Bobby: I like to surround myself with people who are better at doing what they do than I am at doing what I do. And I'm a doggone good singer and Hammond B3 player. Now, my piano playing's a little bit rough, but...

Coco: Stop. No it's not. It's great.

Bobby: Well, it's real basic.

Coco: He put a piano on a track that I'm doing. I'm producing a friend here, his name is Gary Graves. He's brilliant. Bobby put a piano on this track of his, and it sounded so Bobby, it was brilliant. It just brought the whole thing to life.

Bobby: Gary's incredible. I did nine organ tracks in one day. I've never put down nine organ tracks even for myself, but we did nine in one day.

But when something is natural, when something feels right, you don't have to go searching for what to play, it happens immediately. It's like the pitcher throwing a great fastball, I don't even have to move my glove.

I was going to be a professional ball player when I was young, and I liked being the catcher, that was my place. Started out second base, went to catching because the catcher kind of runs the game. But, boy, when they throw one in there and you don't even have to do nothing, just set the target, Boom! there is it. It's no different than being with somebody like Coco, who does it exactly right. Eric Clapton, who plays exactly the right thing.

Coco: That's pretty high praise for me, I have to tell you. I don't see it that way.

Bobby: I never told her one thing to play or sing, ever. So that pretty much speaks for itself.

Songfacts: Bobby, did you write the song "Where There's a Will, There's a Way" with Bonnie Bramlett?

Songfacts: You did?

Bobby: Yeah. She had nothing to do with it. They talked me into signing with their publishing company, Delbon. And I was the only person to ever sign to that company.

Coco: Well, the songs were Delaney's and he was trying to protect himself, so he put them all in Bonnie's name, and that's how her name got on there to begin with.

Bobby: Yeah. She never wrote any songs. That came out of the divorce thing.

Coco: The three of you wrote "Alone Together."

Bobby: "Alone Together" is the only one. That was when I first went out there, and that was kind of the hook to keep me out there. But we never did anything after that.

I wrote ballads. "Walk Softly" was the first song I ever wrote. I was 14 years old. "Dreams of a Hobo," I was 15, wrote it in my front yard in Millington, Tennessee. But I asked Delaney one time. I said, "Man, you write all these great rock n' roll songs." He said, "You can do that. Just put a different rhythm and change the tempo, put a different beat to it." I didn't think about that. It was so simple.

I went home and I started [singing], "Honey, when we're together..." and I wrote the whole, "Where There's A Will, There's A Way." Called Delaney and he said, "Man, that's great, we're going to do that on a show."

I thought I was going to do it on the show. No, he wound up doing it and he said, "This is a little song we wrote." He never once acknowledged that I wrote the song.

I took it to them for our rehearsal, and the next thing you know he's singing my song and they both got writer's credits on it. And neither one of them were in the building, kind of like Keith Richards on "I Just Want to See His Face." He was not even in the building, much less playing piano on that.

Coco: There was a lot of that kind of thing that went on in those days. I'm sure that it still does, and that's why I'm always onto young writers about protecting themselves. But it was the same with "Never Ending Song of Love." Carl Radle wrote that.

Bobby: Yeah, Carl Radle wrote that.

Coco: Brought it to Delaney, next thing you know it wasn't his.

Bobby: And boy, what an upset that was for Carl. He wouldn't write again. That was the end of it, his songwriting.

Songfacts: It seems like Austin is a perfect place for you both. What is the lifestyle like for you guys down there?

Coco: It's pretty casual. We don't go out much and we do our gig. It keeps the juices flowing and keeps us playing. We pretty much keep to ourselves.

Now that we've decided to go out on the road, all of a sudden we're touring, we're being invited to go play in all different kinds of places. It's a good central place for us to be. We can drive to just about anywhere from here, so that's good for us.

Bobby: Her family's just over 1,000 miles away. Mine's about 400 in Memphis. It's just right for us. They had Bobby Whitlock Day here. That was nice, I appreciate that.

But we live on a farm, a 28-acre farm right on the edge of town. Two old houses that used to be downtown, they moved them out here some 30, 40 years ago. It's got three barns and two old Texas farmhouses, looks like Texas Chainsaw Massacre. It's that kind of house. It's got porches all around.

Coco: It's beautiful. It's nothing like Texas Chainsaw anything.

Bobby: But the end of our driveway is Austin, and our house is in the country. We're considered in the country. The house and the barns and everything.

Walnut Creek runs through our place. It's quite beautiful, actually, and it's real laid-back. And Austin is a real laid-back place. When we came here, we were pretty much escorted out of wherever we went, because nobody really knew what the deal was - they believed all those lies that were being told about Coco and me, and it was just awful. But that's all right. We came here.

One time, just to check out one gig, we went out to this little coffee shop and there were tons of people with tattoos. In the South there's a church on every corner and maybe one or two tattoo parlors that you have to find. Here, there is a tattoo parlor on every corner and maybe one or two churches you have find, if you happen to be looking for one.

But when we got here, we met Leslie [Cochran - local legend], and he was wearing a tutu. Everybody loves this guy, and I thought, If they'll accept Leslie here, they'll accept us. And I was right.

Coco: It's a real warm place. There's a lot of friendly people, and a lot of the people that have been here are the original Austinites. They hate to see the way things are going here, because it's growing very, very quickly.

Bobby: We've got all these billionaires moving into town.

Coco: A lot of very wealthy people from Texas, so the old music scene is sort of disappearing. That's kind of heartbreaking for the people that have been here for a very long time.

Songfacts: I'm confused about something here. Bobby, you said that when you guys got there, you were escorted out, they were telling lies about you. I don't understand that.

Bobby: Not here in Austin. Not here.

Coco: Oh, no. He's talking about the other places that we were. We've been sort of escorted out of every place we've lived.

Songfacts: Really? I don't understand that. Why would that be?

Coco: Because of all the badmouthing that was going on, because when we had gotten together.

Bobby: Yeah, because everybody swore that we had had an affair.

Coco: I really don't even want to get into all that.

Bobby: Well, I'll get into it real quick so we'll clear this up. I went out to see Delaney, who was in the hospital getting ready to go into rehab for the 19th time. They didn't think he was going to make it, so I flew out to see him. I was in California two days, and the second day I was there, we went to see Jack Tempchin at a place called The Joint down in Hollywood. Jack's a songwriting buddy of mine.

I went back home and left the next day. I slept in the poolhouse at Delaney and Coco's place. And when I got back to Mississippi, it was like something was up. A switch had been flipped.

I lived way out in the country in Mississippi. My nearest neighbor was two-and-a-half miles away. I lived three-and-a-half miles up a gravel road, and 18 miles from Oxford and 15 from Holly Springs, Mississippi. And it was like, something is going on around here. I don't know what.

They had accused us of having an affair, which was not true. And telling all these lies about us. It was just horrible.

Coco: It got really bad. There was bad stuff all over the Internet.

Bobby: Yeah, they were using the Internet, and there was nothing we could do about it, because that character assassination had already started.

It created a perfect storm for me to leave Mississippi and put that place behind me. And I did. I had a 300 acre farm.

Coco: So, at the end of all this, there was a lot of hatred being aimed at Bobby and me. There was no way of escaping it and everyplace we went this news was there. We were like these tarnished beings, so we were not welcome. And then when we spoke to Stephen Bruton, he just loved us, he said, "You guys need to come to Austin." So we did. And we've been here ever since.

Bobby: Here we stay. And all the people who were saying all those bad things about us when we first got together, now they want to be close to us.

Coco: I think it's like anything, it all gets forgotten. It was all pretty stupid and pathetic, anyway.

Bobby: Yeah, it was. But what it did do, it shoved Coco and me together. And the more they tried to tear us apart, the tighter we clung to each other.

Songfacts: I can see how you guys would need to put up a unified front. And also in Austin, it just seems like the two of you are such a valuable resource. Bobby for very obvious reasons, and Coco, you succeeded in an industry that continues to be male-dominated.

Coco: Doesn't affect me at all.

Songfacts: How were you able to deal with that?

Coco: I don't pay any attention to it.

Bobby: I tell you what she does do. She garners the respect of our fellow musicians by just doing what she does. She doesn't toot her own horn. She actually plays it.

Coco: I've never let any of that affect me. When I was in London, it was really bad there. Worse than anything I'd ever seen. They were very male-dominated and were really disrespectful toward any women players. But at that time there was very few women players around, and I just went out and I played. I got up with people and I played with people, and I never let that really affect me. So I just had to break through it that way.

I had people making fun of me and doing things that weren't very pleasant.

Bobby: I could tell you one thing, when she does play, the mouths shut up.

Coco: I learned from that experience. I just took it and it made me better. And now, I don't even think about that kind of thing. If they've got a problem, I don't know about it.

Bobby: I'll tell you what I love to watch. When we got together, I said, "Well, we're just going to go out and play." Well, we went to sit in down in Muscle Shoals - some guys invited us to come out. And Coco brought her sax. They called us up and I got up. And here Coco comes. I could see them looking at each other, "Yeah, look at him and his girlfriend with her little horn there." These guys are the Muscle Shoals rhythm section - David Hood and Roger Hawkins and Kelvin Holly - some real players. They're all friends of ours to this day. But they're looking at each other, like, "Yeah, watch this."

Boy, when she picked up that horn and started playing, I made it my business to look at every one of them. And every one of them's mouth dropped wide open. They looked like Duane Allman when he's hitting the hot lick, you know how his mouth is open? That's what these guys looked like. I felt like reaching back and grabbing Kelvin's chin and pushing it up for him.

Coco: When I was with Delaney, he absolutely loved my horn playing and my drum sounds when we were recording. By having that from Delaney, nobody ever questioned it. Must be okay, because Delaney thinks it's good.

Bobby: Coco's engineering and production prowess comes from Delaney through Tom Dowd. He got his expertise and knowledge from working with Tom in the analog field, and then Coco picked hers up through Delaney. She came up through an analog world and crossed that border into the digital, so she operates digitally with an analog mind, and it's pretty amazing.

She's Tom Dowd technique vicariously. And aside from Tom, she's the best producer/engineer that I've worked with ever.

Coco: Well, we were doing our shows here at the Saxon, and this guy kept contacting Bobby, pretty much just driving him crazy to the point where he didn't even want to listen to him. He said, "You've got to have this guitar player, you've got to meet this guitar player."

Bobby: He sent me a bunch of videos.

Coco: Finally, he listened to it. And the guy that I'm referring to, his name was Tolo Marton, and he's an Italian guitar player. It turns out the guy's really phenomenal. He's a great guitar player.

We said, "Sure, just have him come along, set up, we'll just play." So we did, and as soon as he started to play, we thought, Wow, we're missing out on something. It'd be nice to have a guitar player playing with us.

So when we were setting up the tour, we thought, We should have a guitar player come sit in every time we do a show. So that's how it started. And then one by one they were volunteering to do it.

Bobby: The premier guitar players in every city that we're playing. And every guitar player in the world knows all my songs.

Coco: They know those songs. They want to play those songs.

Bobby: The Layla album is the guitar player's Holy Grail. So they all already know "Tell The Truth," "Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad," "Bell Bottom Blues," "Keep On Growing," "I Looked Away," "Anyday," "Thorn Tree in the Garden," they already know these songs.

Songfacts: Wow, that's a really interesting concept and a great way to keep it fresh. And to keep it local.

Coco: It's really exciting for us, because every time we're getting ready to do a show, it's going to be like, "Oh, today's going to be Kelvin Holly."

Bobby: Moses Mo is going to play with us. He's with Mother's Finest. He's going to play with us down in Atlanta.

Coco: Andy Argondizza, he's going to be playing with us. Every time we get up to do a new show, we're going to have a new guitar player. So it's going to be really fresh for us, fresh for them.

Bobby: And everybody's excited knowing that we're doing all the original Layla material.

Coco: It's going to be a ton of fun. And I just see it actually growing into something bigger.

August 12, 2015

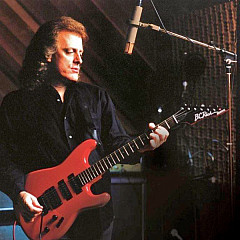

Photos: Todd V. Wolfson (1), Marc Bowman (2).

More Songwriter Interviews