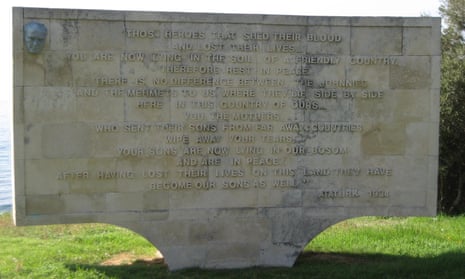

Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives ... You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours ... You, the mothers who sent their sons from faraway countries, wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well.

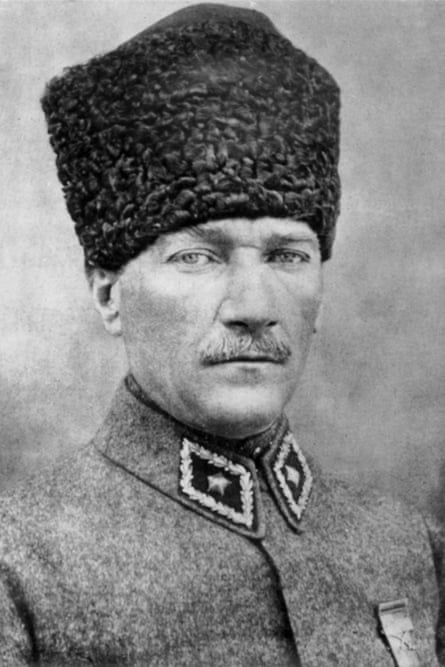

These famous, heart-rending words, attributed to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who was a commander of Ottoman forces at the Dardenelles during the first world war and later the founder of modern Turkey, grace memorials on three continents, including at Anzac Cove, Gallipoli. A procession of Australian prime ministers, from Bob Hawke to Kevin Rudd to Tony Abbott, have spoken them to invoke a supposedly special bond between Australia and Turkey forged amid the slaughter of the 1915 Gallipoli campaign in which some 8,700 Australian and more than 80,000 Ottoman troops died.

As Australia prepares to commemorate the centenary of the British invasion of Gallipoli on 25 April, the authenticity of these emotive words, supposedly uttered in 1934 and interpreted in Australia as a heartfelt consolation to grieving Anzac mothers, are being challenged with assertions that there is no credible definitive evidence Ataturk ever wrote or spoke them.

Cengiz Ozakinci, a Turkish writer about his country’s politics and history, has spent a decade researching the purported Ataturk quote.

“The words that appear with the signature ‘Ataturk 1934’ in the English inscriptions on the monuments ... do not belong to Ataturk,” he writes in the April edition of the Turkish scholarly cultural journal Butun Dunya.

Meanwhile the Australian organisation, Honest History, has undertaken its own detailed research. It says the words are set in stone in Anzac memorials “without proper evidence”.

Today Honest History, which is supported by some of Australia’s leading historians and writers, publishes documents relevant to its research on the purported Ataturk speech.

David Stephens, secretary of Honest History, said: “They are lovely words but we really don’t know that Ataturk ever said or wrote them. It detracts from the dignity of commemoration, whether it is in speeches or memorials, if we keep quoting these words and putting his name under them without proper evidence. Doing it again and again, as we have done in Australia and Turkey, just sets in stone what may well be a myth.”

And no myth endures in Australia quite like Anzac.

An apparent historical miscarriage

Sentimentality, decades of Anzac mythologisation, sloppy Turkish-English interpretation, and diplomatic convenience appear to have manifested in a historical miscarriage that attributes to Ataturk, who died in 1938, words and sentiments for which there is little but unreliable hearsay evidence that he composed or spoke.

Commonwealth departments, state governments, local authorities and the Australian War Memorial have officially asserted Ataturk “delivered” and, or, wrote the words in 1934 to the first delegation of British, Australians and New Zealanders to visit Gallipoli.

The Turkish embassy in Australia calls them “Ataturk’s words to the Anzac mothers”.

Kevin Andrews, the Australian defence minister, opened a recent international Gallipoli symposium in Canberra with “Ataturk’s own words”. A British conference speaker observed that the words have become the single most frequently quoted piece of writing about Gallipoli and were mentioned at least four times on one day alone at the conference.

Generations of journalists have referred to the words. In an article about the Anzac legend in 2014 the New York Times reported: “In 1934 Ataturk famously wrote to Australian mothers saying ‘having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well’ ”. They have made it into the Guardian as well.

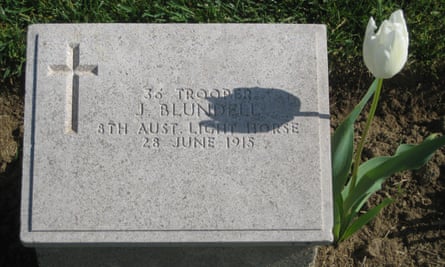

One Australian, Captain Harry Wetherell, who served on Gallipoli with the 5th Australian Light Horse Regiment, was among 700 guests in a delegation organised by the Royal Naval Division Officers’ Association that sailed to the Dardanelles aboard the Duchess of Richmond in April-May 1934. They laid wreaths at numerous sites.

But mention in the day’s English or Australian press of the famous words being spoken on behalf of Ataturk are hard to find. Surely, had such emotionally resonant words for the British empire been spoken on Ataturk’s behalf – as so much Turkish and Australian history asserts they had been by his interior minister and long-time political ally, Sukru Kaya – they would have been reported?

Journalists and writers covered the pilgrimage. They included the English Gallipoli veteran Stanton Hope, who filed for British papers and the Sydney Morning Herald.

“A Turkish delegation led by the governor of Chanak added their tribute both at Lone Pine and the New Zealand memorial on Chunuk Bair,” Hope wrote. But he made no mention of Kaya in any contemporary article. Later in 1934, Hope’s book, Gallipoli Revisited, offered a detailed account of the pilgrimage. It doesn’t mention Ataturk’s purported speech, although it includes a photograph of Kaya at a wreath-laying ceremony.

The pilgrims did, however, hear briefly and indirectly, from Ataturk who – according to the Sydney Morning Herald – “sent a message of greeting to the British ambassador to Turkey who presided at the ceremonial luncheon on board the liner”.

It read: “I am much touched by your cordial telegram. I send warmest wishes to all of you during your devout pilgrimage.”

On Anzac Day 1934, in response to a request from an Australian newspaper, the Star, Ataturk had written what was immediately considered to be an Anzac tribute, even though he made no mention of Australians or New Zealanders: “The landing at Gallipoli on April 25, 1915, and the fighting which took place on the peninsula will never be forgotten. They showed to the world the heroism of all those who shed their blood there. How heartrending for their nations were the losses that this struggle caused.”

Ataturk’s message to the Star was republished with slight variations in other newspapers across the world.

Four years earlier, Ataturk – again responding to an Australian media request – did specifically praise Anzacs, reportedly saying: “Whatever views we of the present or future generations of Turks may hold in regard to the rights or wrong of the world war, we shall never feel less respect for the men of Anzac and their deeds when battling against our armies … They were nearer to achieving the seemingly impossible than anyone on the other side yet realises.”

These are, undoubtedly, laudatory sentiments about the Anzacs. But they lack the emotive resonance of the purported – and now contentious - 1934 “Johnnies and the Mehmets” speech attributed to him.

Ataturk, again responding to a request, told Brisbane’s the Daily Mail on Anzac Day 1931 that the Anzacs were a worthy foe. These words come closest to anything I’ve seen to his purported 1934 speech inscribed on the monuments. “The Turks,” he said, “will always pay our tribute on the soil where the majority of your dead sleep on the windswept wastes of Gallipoli.”

These, and other words from his statement to the Daily Mail, have the same poetic ring – perhaps even the same emotional and diplomatic intent – as “the Johnnies and the Mehmets” speech. But they are not the same.

Ataturk died in 1938. Australian obituaries followed. It is curious the famous Johnnies and Mehmets speech received no mention here with his passing, given it was supposedly delivered in 1934.

In its obituary Adelaide’s the Advertiser, for example, said: “One cannot pass from this phase of his remarkable life without recalling the message which he sent to the Australian government [sic] four years ago on Anzac Day.” The paper then quoted the message that Ataturk had sent to the Star.

‘Beautiful words’

So precisely how and when did the “Johnnies and the Mehmets” words make it into the public consciousness in Turkey and Australia?

In November 1953, the Turkish newspaper Dunya published an interview with Kaya in which he says he delivered a speech at Gallipoli in 1934 drafted by, and on behalf of, Ataturk, praising the Turkish and enemy troops. Ozakinci says the words Kaya claimed to have spoken are: “Those heroes that shed their blood in this country! You are in the soil of a friendly country. Rest in peace. You are lying side by side, bosom to bosom with Mehmets. Your mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries! Wipe away your tears. Your sons are in our bosom. They are in peace. After having lost their lives on this soil they have become our sons as well.”

In 1960 the president of the New South Wales Returned Sailors’ Soldiers’ and Airmens’ Imperial League of Australia, Bill Yeo, led a delegation of 45 other Gallipoli veterans to the Dardanelles. According to Brisbane’s the Courier Mail of 25 April, 1964, at Gallipoli they were read “a special message from the Turkish government”.

The message included: “Oh heroes, those who spilt their blood on this land, you are sleeping side-by-side in close embrace with our Mehmets. Oh mothers of distant lands, who sent their sons to battle here, stop your tears. Your sons are in our bosoms. They are serenely in peace. Having fallen here now, they have become our own sons.”

The words – while literally similar, and evocative in emotional tone and intent of those questionably attributed to Ataturk on memorials at Anzac Cove, on Anzac Parade in Canberra and in New Zealand’s capital, Wellington – do not mention “the Johnnies and the Mehmets” together.

Fast forward to a chance encounter on the Dardanelles between a retired Turkish schoolteacher, Tahsin Ozeken, and an elderly Australian Gallipoli veteran on 15 April, 1977. Ozeken carried a Gallipoli Peninsula guidebook, Documented guide for Eceabat, published in 1969.

Ozeken read to the Gallipoli veteran a section from the book he attributed to Ataturk: “Those heroes that shed their blood in this country! You are in the soil of a friendly country. Rest in peace.

“You are lying side by side, bosom to bosom with Mehmets. Your mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries! Wipe away your tears. Your sons are in our bosom. They are in peace. After having lost their lives on this soil they have become our sons as well.”

Other English translations vary slightly. None include the words “no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets”. None even mention the “Johnnies”.

The veteran, delighted at Ataturk’s purported words, swapped personal details with Ozeken.

Ozeken wrote the words down for the veteran to take home, which he did, and read them to a Brisbane Anzac veterans’ meeting.

Ozeken, in an October 1977 letter to Ulug Igdemir, head of the Turkish Historical Society, said he’d “mentioned [to the Australian] the remarkable statement which I suppose had been made by Ataturk while on a visit to ... the battlefields in the years between 1928-1931”.

Ozeken’s letter to Igdemir enclosed another from an Australian Gallipoli veteran, Alan J Campbell, of Brisbane, who identified himself as “chairman of the Gallipoli Fountains of Honour Committee”. Campbell, a stalwart of the Queensland Country party, wrote that his organisation was finalising a Gallipoli memorial for Brisbane.

“We were all very impressed by your quotation by that greatest Turk, Ataturk, by the side of Quinn’s post at Anzac, we think it a very wonderful statement and we would be anxious to have it inscribed upon a metal plaque on the Fountains,” Campbell wrote.

According to Igdemir (who reproduces letters between Ozeken, Campbell and himself in his society’s 1978 book, Ataturk and the Anzacs), Ozeken asked Igdemir to send the statement made by Ataturk “concerning the foreign soldiers that had fallen dead in Gallipoli to Mr Campbell after having it supported with some official confirmation as to the accuracy of its date and the place of its deliverance”.

Igdemir drew a blank, writing that the guide book “has provided no sources whatever” and that he could find “no information concerning the visit of Ataturk to the battlefield in the Dardanelles and the talks delivered by him in the area”.

But writing in Ataturk and the Anzacs, Igdemir recounts how he told Campbell by letter that he had found a reference in a November 1953 newspaper article to an interview with Ataturk’s then ageing former interior minister, Sukru Kaya. The special edition of Dunya newspaper coincided with the 15th anniversary of Ataturk’s 1938 death.

Ozakinci has spent a decade researching the purported Ataturk speech and concludes neither Ataturk nor Kaya publicly delivered the words in 1934. He took up the story of the Campbell-Igdemir correspondence in a two-part feature in Bütün Dünya, a cultural periodical attached to Baskent University, Ankara.

In his article, “The words ‘There is no difference between the Mehmets and the Johnnies’ … do not belong to Ataturk,” Ozakinci writes: “These words that were reported to belong to Atatürk in the Eceabat Guide published in 1969 without any reference, are exactly those words that Sukru Kaya in his interview of 1953 reports Atatürk himself to have written and given to him [to speak in 1934].”

The 1953 Turkish newspaper interview with Sukru Kaya is therefore critical. It appears to be the first time that the purported speech (minus the Johnnies and the Mehmets together) that closely resembles that which has so famously been attributed in English to Ataturk on monuments (including references to “the Johnnies and the Mehmets”), made it on to the public record, even though they were supposedly spoken in 1934. Ozakinci says the words attributed to Ataturk in that newspaper interview are the same as those the 1969 Eceabat guidebook assigns to him. They are also similar to those Yeo heard spoken at Gallipoli in 1960.

So how, then, did the line “There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours” make it first on to the brass plaque on the now obsolete Gallipoli fountain memorial in Brisbane, arranged by Campbell and dedicated by his friend the Queensland premier, Joh Bjelke-Petersen, in 1978?

The answer, it seems, is a poetic addition Campbell apparently took upon himself (and perhaps others) to insert.

According to Igdemir’s book, Igdemir wrote to Campbell on 10 March, 1978, with an English translation of Kaya’s purported 1934 speech for Ataturk – the same Turkish words that appeared in the 1969 Eceabat guide book without “the Johnnies and the Mehmets” together.

On 7 April, 1978, Campbell responded that the English translation of the words supplied by Igdemir from Ataturk’s purported speech (supplied by Igdemir and taken from Kaya’s newspaper interview) had now been placed on a brass plaque at the Roma Street, Brisbane, memorial.

“It varies slightly with the advices you have sent me. But the difference makes no difference in solemn meaning and inspiration,” Campbell wrote, according to Igdemir.

On 18 April, 1978, Igdemir, evidently wondering what changes to Ataturk’s purported speech Campbell had made, wrote: “I shall be grateful should you send … a photograph taken at close range of the metal plaque, upon which the statement of Ataturk has been inscribed.”

On 31 May Campbell replied with three photographs of the monument, including a plaque close-up.

Ozakinci elaborates in his article: “These words that were reported to belong to Atatürk in the Eceabat Guide published in 1969 … are exactly those words that Şukru Kaya in his interview of 1953 reports Ataturk himself to have written and given to him.”

Ozakinci goes on: “Igdemir sends an official letter to Alan J. Campbell . . . translating into English these words, which he considers to be ‘a very meaningful speech that Ataturk had Şukru Kaya read out in Gallipoli in 1934’ … Campbell informs Igdemir that they added these words to the monument made in Australia making slight alterations and with Ataturk’s signature under them and sent Igdemir a photograph of the monument together with a letter dated May 31, 1978.

“A look at the photo reveals that the slight changes made by the Australians are (ı) adding the statement ‘there is no difference between the Johnnies and Mehmets to us’; (ıı) changing the date 1934 sent by Igdemir into 1931; (ııı) changing Ataturk’s first name Kemal into Kamel.

“In his response to Campbell on June 8, 1978, Igdemir points out that the year 1931 should be changed into 1934, and Kamel into Kemal; however, he did not ask for removal of the statement ‘there is no difference between the Johnnies and Mehmets to us’ that the Australians added to the monument as Atatürk’s words, and expresses that he likes the addition to ‘Atatürk’s beautiful words’.”

In Ataturk and the Anzacs, Igdemir – whose state-sponsored official history society Ataturk founded in 1931 – uses two versions of the purported 1934 speech: one in Turkish with no mention of the Johnnies, and the amended one with the addition of them that he had apparently later accepted from Campbell.

Of the famous statement attributed to Ataturk in 1934 that adorns Anzac monuments, the speeches of Australian prime ministers and which stands as a cornerstone of the Anzac legend, Ozakinci writes: “However, in 1934 Ataturk did not give such a speech.

“The words that appear with the signature ‘Ataturk 1934’ in the English inscriptions on the monuments erected in Canberra (Australia), Wellington (New Zealand), and Ariburnu (Turkey), that address . . . ‘The Johnnies’ (Anzac soldiers) and their mothers, and that include the expression ‘There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets’, which we have proven to belong to the Australian Alan J. Campbell, do not belong to Ataturk.”

The only statement Ataturk did issue in relation to Australia in 1934 was his brief written statement to the Star newspaper around Anzac Day, Ozakinci writes. Even then, he points out, those words were not specific to Anzacs.

Ozakinci reveals Kaya did make a speech at Gallipoli for Ataturk. But it was in 1931.

He reproduces an official news agency report of a speech Kaya made in August 1931 that, while highly emotive and paying passing tribute to foreign soldiers who died at Gallipoli, gives far greater emphasis to the bravery of Turkish defenders and refers to the force in which the Anzacs fought as “invaders”. The words demonstrably spoken in 1931 by Kaya at Kemalyeri, Gallipoli, on his leader’s behalf carries little of the tone of the contested 1934 Ataturk speech.

According to Ozakinci’s English interpretation of the speech, it reads in part: “With honour and pride do we see that the great states who fought with the greatest force and might against this place look with respect and appreciation at Kemalyeri and the great Turk that it was named after. At this point, I will content myself with one sentence to express my whole emotionality: endless gratefulness to the Turkish youth who shed their blood to save the fatherland.

“I see that for these big heroes no monument has yet been erected. I would like not to be grieved by this. We know that the indestructible Turkish state that these glorious heroes established and protected is the highest monument of universal nature that will always make them be remembered with love.

“Across we see the graves and monuments of the warriors that fought us. We also appreciate those that rest there ... The history of civilisation will judge those lying opposite each other and determine whose sacrifice was more just or humane and who to appreciate more: the monuments of the invaders, or the untouched traces of the heroes left here in the form of sacred stones and soil, these traces of heroes …

“If the nations that left graves opposite us, consider our sincere and new viewpoint well, these graves that face each other will ensure conversation and friendship between us instead of hatred, animosity, and feelings of self-will … While the Turkish nation looks with respect at these monuments and remember the dead of both sides, the sincere wish that lives in their mind and conscience is for such death monuments never to be erected again, on the contrary, to heighten the human relations and human bonds between those who erected them.”

Ozakinci concludes his article: “While there are so many of Ataturk’s writings, speeches and statements published during his lifetime that contain his sayings related to his views on world peace, is there any need to explain Ataturk’s pacifism and humanity by putting his signature under others’ poetic words, instead of just using his own words?”

The answer is almost certainly no. But the words supposedly spoken by Kaya on Ataturk’s behalf in 1934 have long suited Australia and Turkey since they first vaguely came into Australian consciousness via Bill Yeo about 1960. Their evocation of sleeping brethren – the Johnnies beside the Mehmets – distracts from the reality that British forces, including the Australians and New Zealanders, were an invasion force. The words have also become a convenient touchstone for the close bilateral relationship between old foes and, not least, a symbol of the commemorative cultural (and tourism) value of Anzac.

The myth of Ataturk’s uplifting, consoling, Johnnies and Mehmets speech may well have begun as a Turkish whisper in a newspaper interview with an ageing acolyte and devotee of the dead president in 1953. But it has since become a commemorative roar in Australia and at Anzac Cove, where tens of thousands of Anzac pilgrims visit and read the words on the Ataturk memorial, unveiled in the mid 1980s.

The monument bearing the same words on Anzac Parade, Canberra – the only one to an enemy commander – was dedicated simultaneously.

Was a version of the purported 1934 speech recounted in the Turkish newspaper interview with Kaya in 1953 (minus the Johnnies and the Mehmets together) given to Yeo’s delegation in 1960 by a Turkish official? Was the version in the 1969 Ecebat guidebook (also without Johnnies and the Mehmets) most likely based on that 1953 Kaya interview?

There is no evidence, beyond the 1953 interview with Kaya himself, that what we know as Ataturk’s purported “Johnnies and the Mehmets” words were ever written of spoken by the leader, Kaya or anyone else in 1934, 1931 or, indeed, any other time up until the Turkish president’s death in 1938. That hasn’t stopped countless other world leaders and officials speaking them countless times since.

Was Kaya, an old man at the time of that interview and perhaps sentimental at the 15th anniversary of the great leader’s death (Ataturk’s remains were reinterred in a mausoleum that very highly emotional, nationalistic day) confusing 1934 with the speech he demonstrably made at Gallipoli for Ataturk in 1931?

Maybe. Even so, the 1931 speech hardly resembles the almost sanctified words that have made their way on to Anzac monuments in three continents – not to mention the lips of various Australian prime ministers. And the odd British one, too.

It all comes back to 1953 and Kaya – who, as a public servant during the first world war, was strongly implicated in the Armenian genocide and later, as one of Ataturk’s ministers, in the massacre of Kurds at Dursim in the late 1930s.

History is always open to interpretation and debate. But good history is grounded in fact.

Until significant, non-circumstantial evidence to the contrary arises, the consolation to Anzac mothers so widely attributed to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk in 1934 can only remain historically dubious.

It is testimony to the potency of Anzac mythology that it hasn’t been more fully tested until now.