Amid the flurry of rainbow-laden corporate logos, sponsored events and news items about gay penguins, it is difficult to turn on a television or set foot in public during June without the reminder that it is Pride Month for LGBT and queer people. This week, New York City is hosting WorldPride in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, with an estimated 4 million visitors expected to participate. Pride has come a long way since its more radical origins, when marchers numbered in the thousands, corporations were far from getting the memo and the stakes in general felt higher.

But there is much to be gleaned from remembering how it once was. George Dudley, a photographer and artist who also served as the first director of New York City’s Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, documented scenes from pride parades in New York City from the late 1970s through the early ‘90s. His images of queer and trans people parading down the streets of Manhattan illustrate an ebullient and joyous atmosphere that feels not too dissimilar from scenes at pride parades today. The circumstances his subjects faced in their daily lives, however, were profoundly different.

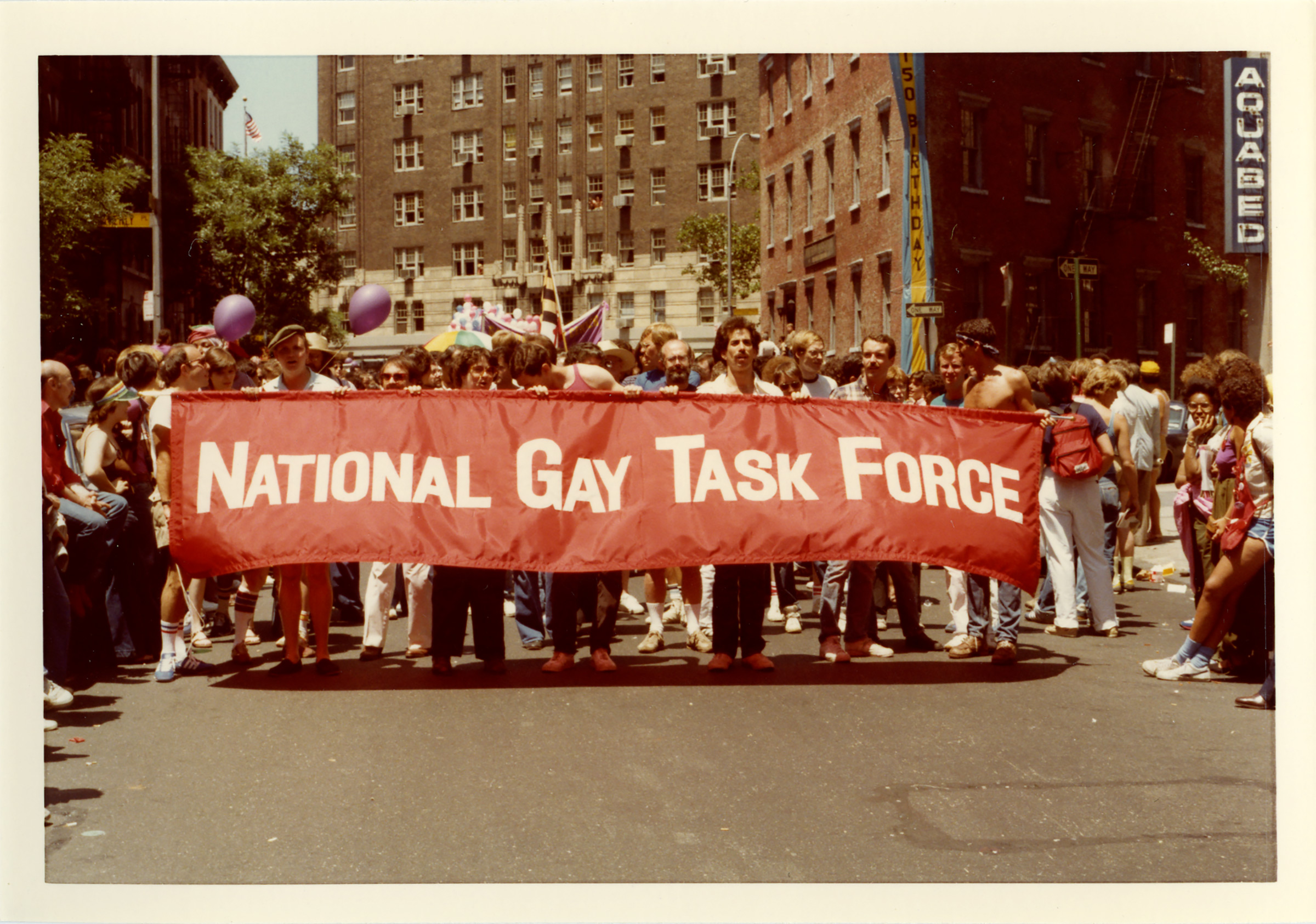

Dudley made the photos in this collection during pride parades between 1976 and 1981. Unlike much of the publicly available photography taken at the first pride parade in 1970 and those that followed, these images were made not by a disinterested photojournalist but by someone deeply entrenched in the community. As a result, the photographs feel warm and intimate. They present the parade not as a newsworthy spectacle but as a gathering of people making themselves visible at a time when the world at large was not interested in seeing them.

There is a certain electricity to these photos too, as they document a time when LGBT communities were bearing witness to significant cultural change. These years saw Anita Bryant’s homophobic crusade through the “Save Our Children” campaign in 1977, the election and assassination of Harvey Milk in 1978, and the White Night riots the following summer after the lenient sentencing of Milk’s murderer, Dan White. And in October 1979, the National March on Washington for Gay and Lesbian Rights took place with roughly 100,000 participants. “It was, in a sense, the year we debuted on the larger public stage,” says Jim Saslow, a professor of art history at the City University of New York and an early gay activist. “We were becoming acceptable enough that a gay person could have a significant political career, but we also became very aware of how much of a nerve that was touching for conservative people.”

Saslow, who was also a friend of Dudley’s, marks this era as a shift in the gay liberation movement. “After 10 years, the movement started to have some visibility, and it wasn’t automatically a kiss of death to be out,” he says. But as the number of out gay people grew, says Saslow, the parades transitioned from intimate gatherings of like-minded people to events attended by a broader array of participants. “The community started to attract more mainstream folks who weren’t necessarily politically radical or countercultural — they just happened to be gay.”

These changes are evident in Dudley’s images, whose subjects range from outspoken activists like Marsha P. Johnson, shown at top, to revelers who conformed more to heteronormative standards. “The guy in a dress with a beard, running in front of the task force banner, captures a lot of the atmosphere of the early gay liberation community, because so much of it came out of the hippie movement,” says Saslow. “A lot of those people were kicking up their heels and having a genderf-ck good time.” Both Saslow and Dudley participated in so-called “genderf-ck drag,” which he distinguishes from “classic drag” in that they kept their beards and body hair and were more concerned with breaking gender norms as a form of protest. “There was a sense in those days of, ‘We’re just going to have fun and do silly, outrageous, non-binary, non-conformist things, and it was a time when everything was sort of amateur night.”

On the other end of the spectrum, the mustachioed men depicted in the photos, dressed in tight shirts and appearing to adhere to more traditional stereotypes of masculinity, were known as “clones.” Many of these men were less interested in making radical or counter-cultural statements, focused as they were on presenting as acceptable to the general public.

When Gonzalo Casals, the current director of the Leslie-Lohman Museum, looks at Dudley’s photos, he laughs. “It brings a smile to my face when I see his work, because it’s very serious, and at the same time so playful and celebratory.” These photos, and the hundreds more Dudley took of protests, parades, LGBT nightlife and house parties, are a part of a larger collection of ephemera and documentation of LGBT people in New York that the museum maintains.

Partners Charles Leslie and Fritz Lohman began to exhibit art by gay artists in their SoHo loft in 1969, the same year the Stonewall uprising took place. They continued showcasing and archiving art made by the LGBT community, functioning as a gallery where artists could sell their work, before transitioning to a museum and foundation in 1987. As the first director of the foundation, Dudley took it upon himself to amass an archive of photography, letters, event posters, magazines and various other personal effects from artists and community members, all of which lends a personal context to the artworks in the collection.

Modern observers could be forgiven for viewing Dudley’s photographs as unremarkable in their ordinariness. But that is much of what makes them so significant. “There weren’t that many people documenting the gay world at that time, so George’s photographs have an enormous importance,” says Saslow. “They capture ordinary people going about these rather radical activities.” With the visibility afforded to LGBT people today, and particularly to gay men, it is easy to forget that embracing on the street was a bold action to make. In those days, says Saslow, “it was a real political statement, and it could get you into a lot of physical and social trouble.”

As tender and joyful as these photos are, devastating loss and tragedy lay just around the corner. These images were made in the last years before the focus of LGBT activism shifted from a narrative of liberation to a reckoning with the devastation of the AIDS pandemic. “The pride that comes out of that happiness and feeling of freedom they had, without the knowledge of what was to come, it feels a little melancholy,” says Casals.

Dudley continued making new work until he died from AIDS-related complications in 1992. Saslow remembers an afternoon visiting him while he was staying in the Cabrini medical center in Manhattan. He and Dudley’s partner had been at the annual drag festival Wigstock, taking place around the corner at Tompkins Square Park, and decided they wanted to tell Dudley about the day. “So we just barged into the hospital in drag and said, ‘We are here to see George Dudley!’” he recalls. “And nobody said a word, and we went up and flounced into the room and he just cracked up because, here he was trapped in a hospital run by nuns, but the drag queens were going to rescue him from this terrible regimen he was under.”

It was just one small act of defiance among close friends. But the spirit of that interaction is the same one Dudley so often captured through his lens: a dignified quest to be visible, to be seen without fear in public, and to be remembered.

“Art After Stonewall, 1969-1989” and “Y’all Better Quiet Down” are on view at the Leslie-Lohman Museum in New York City from April 24–July 21, 2019.

Wilder Davies is the associate partnerships editor at TIME.

Kara Milstein, who edited this photo essay, is an associate photo editor at TIME. Follow her on Instagram @karamilstein.

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now, You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time