Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, not many GE Aviation engineers could walk as tall as John Blanton Sr. Then one of the company’s few high-ranking African Americans, he was known for doing things deemed impossible at the time. Such as charting a futuristic engine for the U.S. Air Force that could push a fighter jet to travel at Mach 3.5, equivalent to roughly 2,600 miles per hour — enough speed to get from New York City to Los Angeles in just over an hour. Or prototyping an engine that could enable planes to take off and land vertically. These engineering feats — as well as his work on a version of GE’s first supersonic engine — landed Blanton in GE Aviation’s Propulsion Hall of Fame in 1991.

But outside of the company’s sprawling complex of factories in southwest Ohio, it was a different story. When Blanton and his family first moved from upstate New York to Cincinnati in 1956, the Queen City was not especially welcoming. Blanton’s son, John Jr. (who they called Buddy), could not go to the swimming pool at Coney Island, one of the city’s local amusement parks. Nor could the family find housing in many neighborhoods. For three years, the Blantons would try to look at houses, only to get rejected for flimsy reasons, all of which seemed like code for racial discrimination.

Choosing engagement rather than conflict, Blanton got to work on improving his new city. He began volunteering in various capacities, eventually becoming a well-known and respected leader in the community. As a founding member and president of the Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority, for example, he built a sustainable future for Cincinnati’s publicly owned bus system. He was also appointed to the Ohio Governor’s Coordinating Council on Drug Abuse, served as president of the Urban League of Greater Cincinnati, and even helped run a local chapter of the Boy Scouts. Though hardly a rabble-rouser, Blanton consistently sought justice and equality for marginalized Cincinnatians.

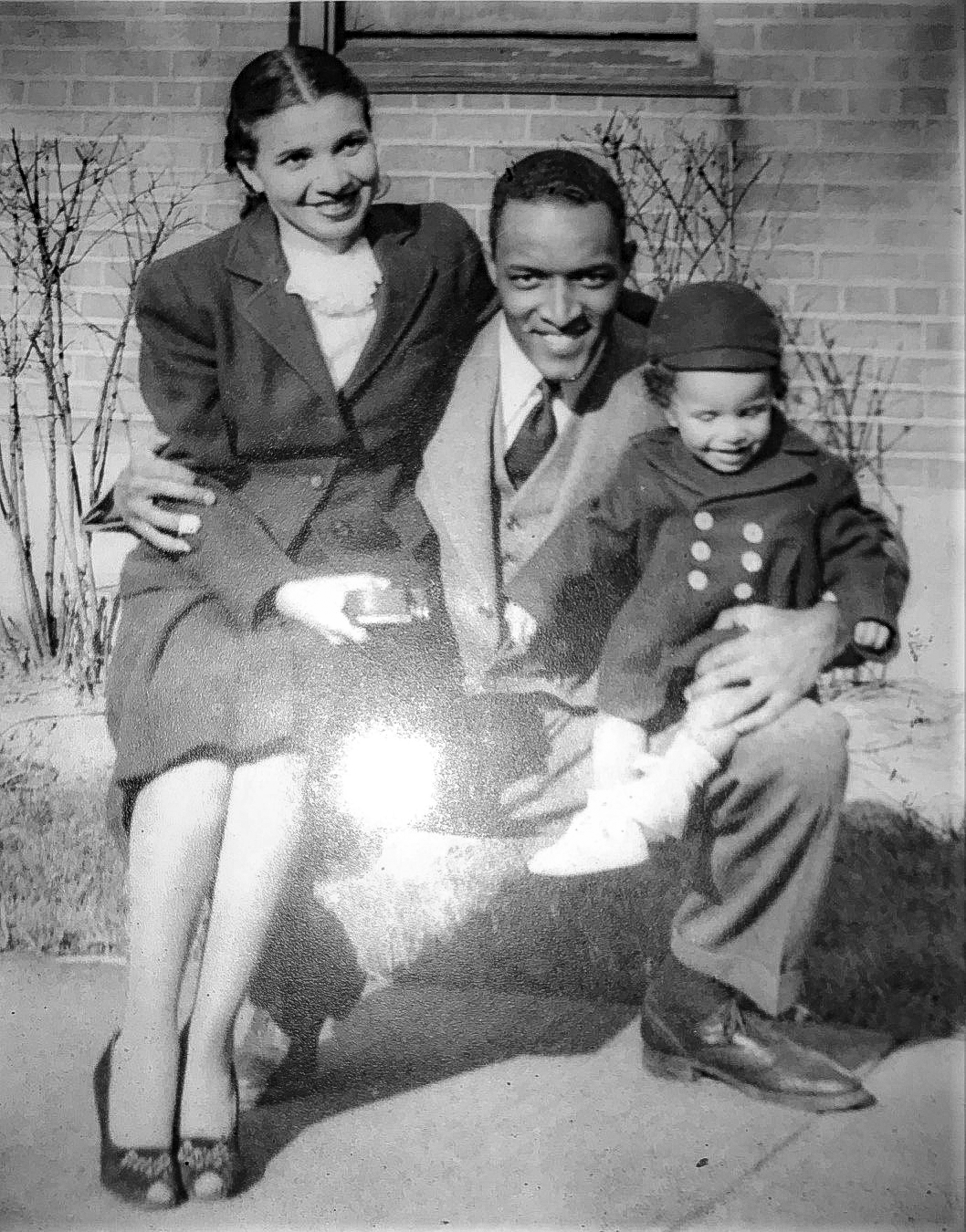

Top: John Blanton Sr. managed several key advanced engine technology programs before retiring in 1982 as general manager for commercial advanced engines and commercial engine programs. Image credit: GE Aviation. Above: The Blanton family on Mother’s Day in 1947. Image credit: Blanton family.

Top: John Blanton Sr. managed several key advanced engine technology programs before retiring in 1982 as general manager for commercial advanced engines and commercial engine programs. Image credit: GE Aviation. Above: The Blanton family on Mother’s Day in 1947. Image credit: Blanton family. After his passing in 2003, Blanton’s story faded into the background. Photos of him lingered in old books and passing mentions remained in GE Aviation’s Propulsion Hall of Fame, but few younger employees knew about him — until one enthusiastic, history-minded 21-year-old came along.

GE Aviation is celebrating 100 years in business this year. Cole Massie, a new addition to the GE unit’s communications team, listened to a lecture from former company spokesman Rick Kennedy to learn more about his employer’s high-flying past. The highlights didn’t disappoint — the company built America’s first jet engine, for instance, and is preparing to launch the world’s largest — but he found himself transfixed by a single story: that of John Blanton Sr.

What struck Massie wasn’t Blanton’s mind-bending engineering, or his commitment to civic duty. It was his character. “You’ll hear around here that GE Aviation is ‘standing on the shoulders of giants,’” Massie said. “I had this traditional, larger-than-life, folklore image in my head, but I think John Blanton gave me a different perspective on that saying. He was humble, he was thoughtful, and he wasn’t flashy or showy in the slightest.”

Fascinated, Massie looked to Kennedy for information to write a profile for a company publication coinciding with Black History Month. He received a mountain of information, but Massie wondered if there might be more. He yearned to find out firsthand who Blanton was. How would his family describe him? Blanton’s obituary mentioned that his son, John Jr., was a retired physician who is now a medical school professor in Connecticut. Massie scoured the internet for his number, called him up, and upon speaking to him, discovered that John Jr.’s mother, Corinne Blanton, 96, was still living in Cincinnati.

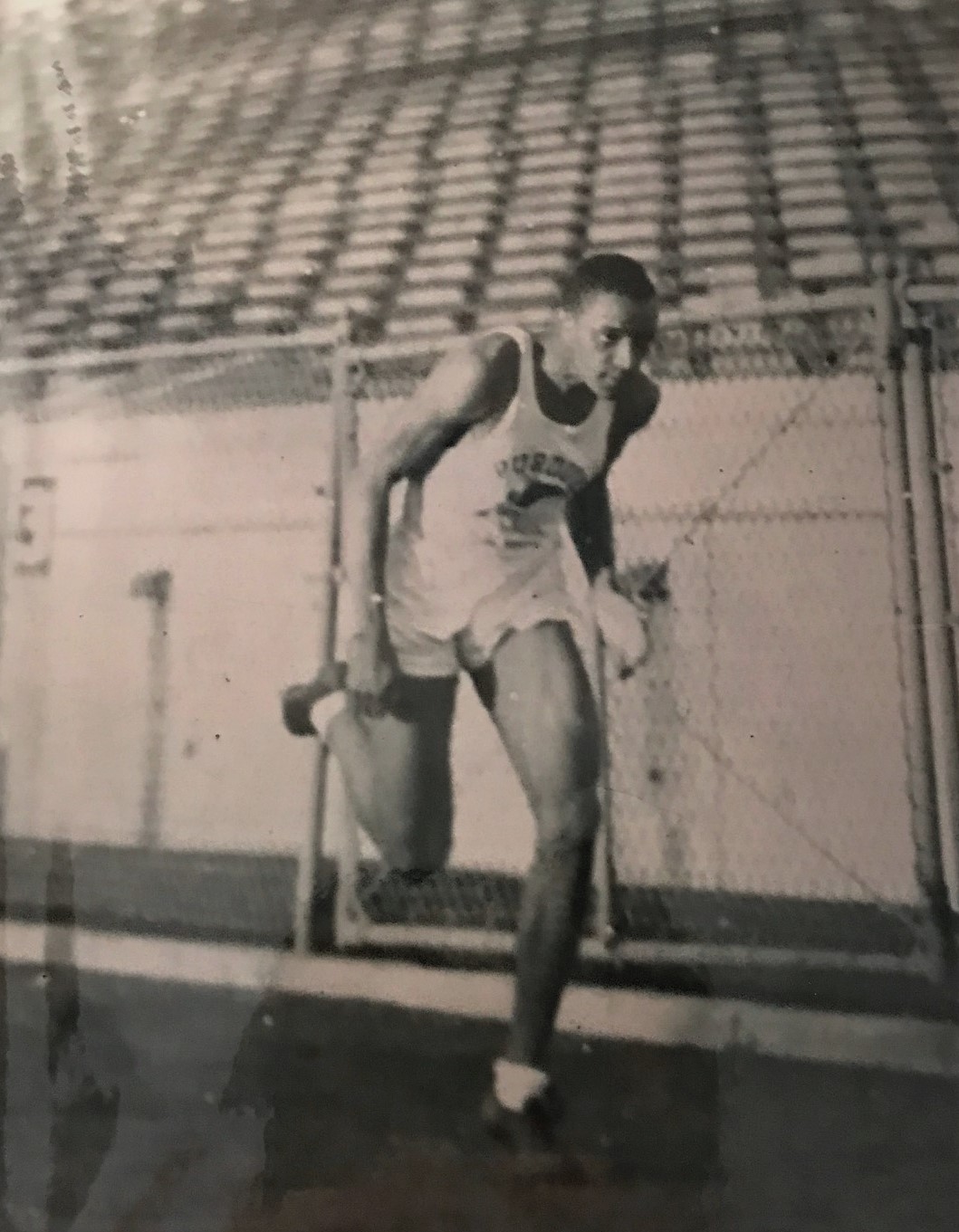

John Blanton Sr. ran track at Purdue University and couldn’t compete in the Big Ten Championships because of his race, according to his wife, Corinne Blanton. Image credit: Blanton family.

John Blanton Sr. ran track at Purdue University and couldn’t compete in the Big Ten Championships because of his race, according to his wife, Corinne Blanton. Image credit: Blanton family.Though Corinne Blanton had shied away from giving interviews in the past, her son convinced her to meet with Massie. She wound up spending two hours, in a recorded interview, poring over old clippings and photos, regaling him with stories about life with John — from their World War II-era courtship at Purdue University to his death in 2003.

Both Corinne Blanton and her son painted a portrait of a quiet, confident man, who steadfastly tended to his passions — work, family and community — regardless of hardships and obstacles. “I didn’t like Cincinnati at all when we moved here,” she told Massie. “For three years, we were living in a four-room apartment looking for the right house. We would find a house to look at, then heard all kinds of excuses about why we couldn’t see it. It was racial.”

The challenges also included persevering through the lower moments of his storied career, such as when two of his most ambitious projects — the Mach 3.5 engine and vertical takeoff and landing technology — failed to come to fruition. “That must have been so frustrating for him,” Massie said. “But the processes and the techniques [he developed for both products] were groundbreaking and used for decades after both projects ended.”

Massie also learned about the lighter moments of Blanton’s private life. Eventually, he and his wife built two different homes — both of which so pleased Blanton that he created his own model versions. After his retirement in 1982, the couple reveled in each other’s company, playing golf, reading The Wall Street Journal and visiting their grandchildren. While Blanton cherished time with his son and grandchildren, he was never one to coddle children. When their son was a baby, Corinne Blanton would overhear him babbling gibberish to his father — to which her husband would answer with straight, matter-of-fact sentences.

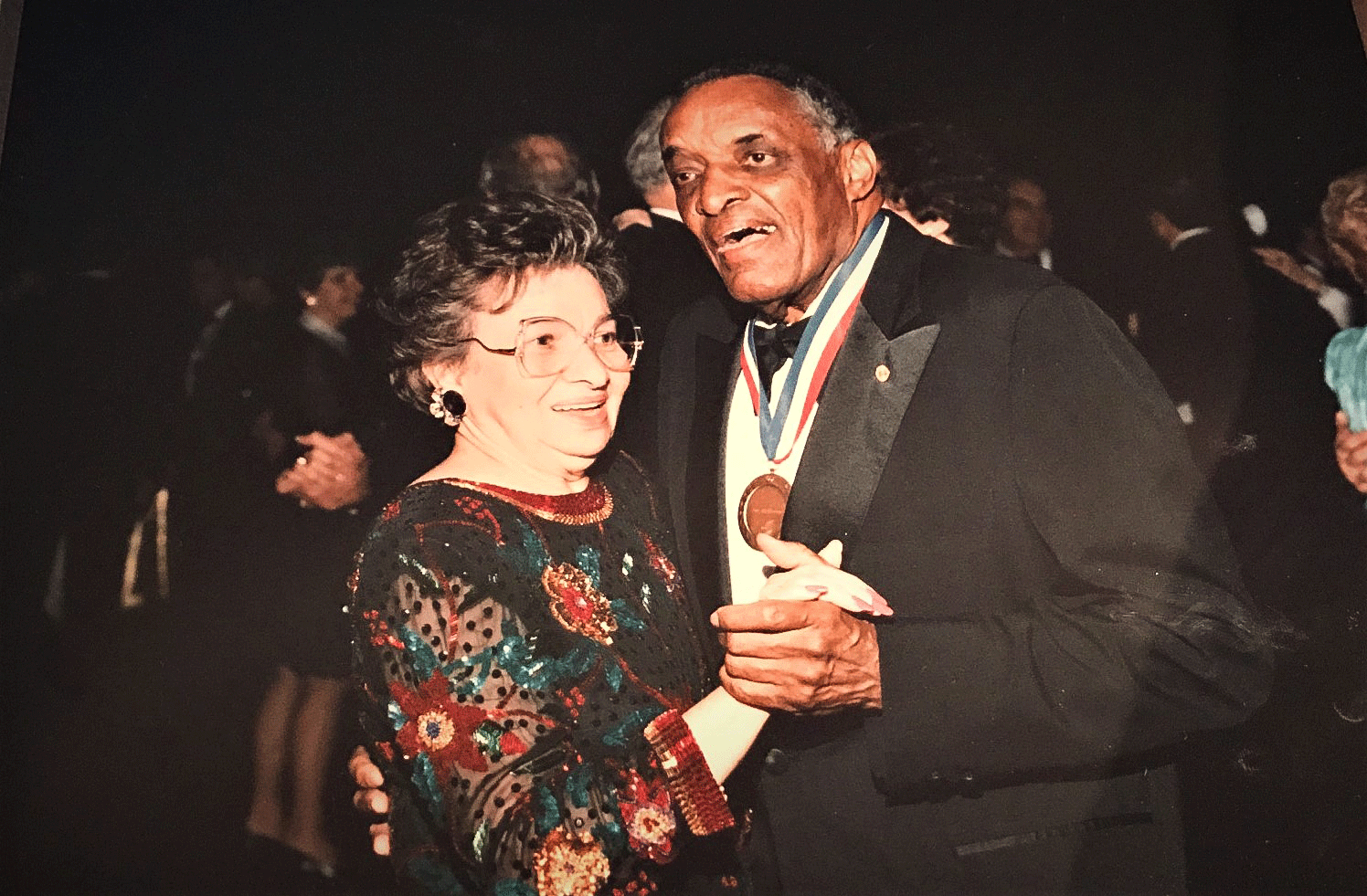

John and Corinne Blanton dance after his induction to the GE Aviation Propulsion Hall of Fame in 1991. Image credit: GE Aviation.

John and Corinne Blanton dance after his induction to the GE Aviation Propulsion Hall of Fame in 1991. Image credit: GE Aviation.Despite his rocky start in Cincinnati, Blanton grew to become one of its most revered citizens. The Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority, for which Blanton served as president from 1973 to 1979, for example, established the John W. Blanton Internship Program in his name in 2014, which seeks to develop leaders in public transportation. “I really do think he felt a deep obligation to give back to his community,” Blanton Jr. said. “And he was grateful for the opportunity to work for a company that encouraged that type of behavior.”

As the conversation with Corinne Blanton went on, she warmed up to the idea of talking to Massie. She concluded with no small amount of satisfaction: “We have covered a life.”

She also lit a path for another one. Massie said Blanton has become a role model for him in his own career. “I’m not going to be building jet engines that push a plane to Mach 3.5 anytime soon,” admitted Massie, who majored in public relations at Syracuse University. “But I can emulate the way he worked and lived — overcoming obstacles, solving problems, treating others with respect, advocating for marginalized groups and giving back. I think those are admirable characteristics that I can strive for not just at GE, but in life.”

In fact, Massie has already begun to do so. He penned a profile of John Blanton Sr. in February for GE Aviation’s blog. And this May, he’ll bring Blanton’s memory to life once more when he steps into the annual GE Aviation Propulsion Hall of Fame ceremony escorting Corinne Blanton herself.

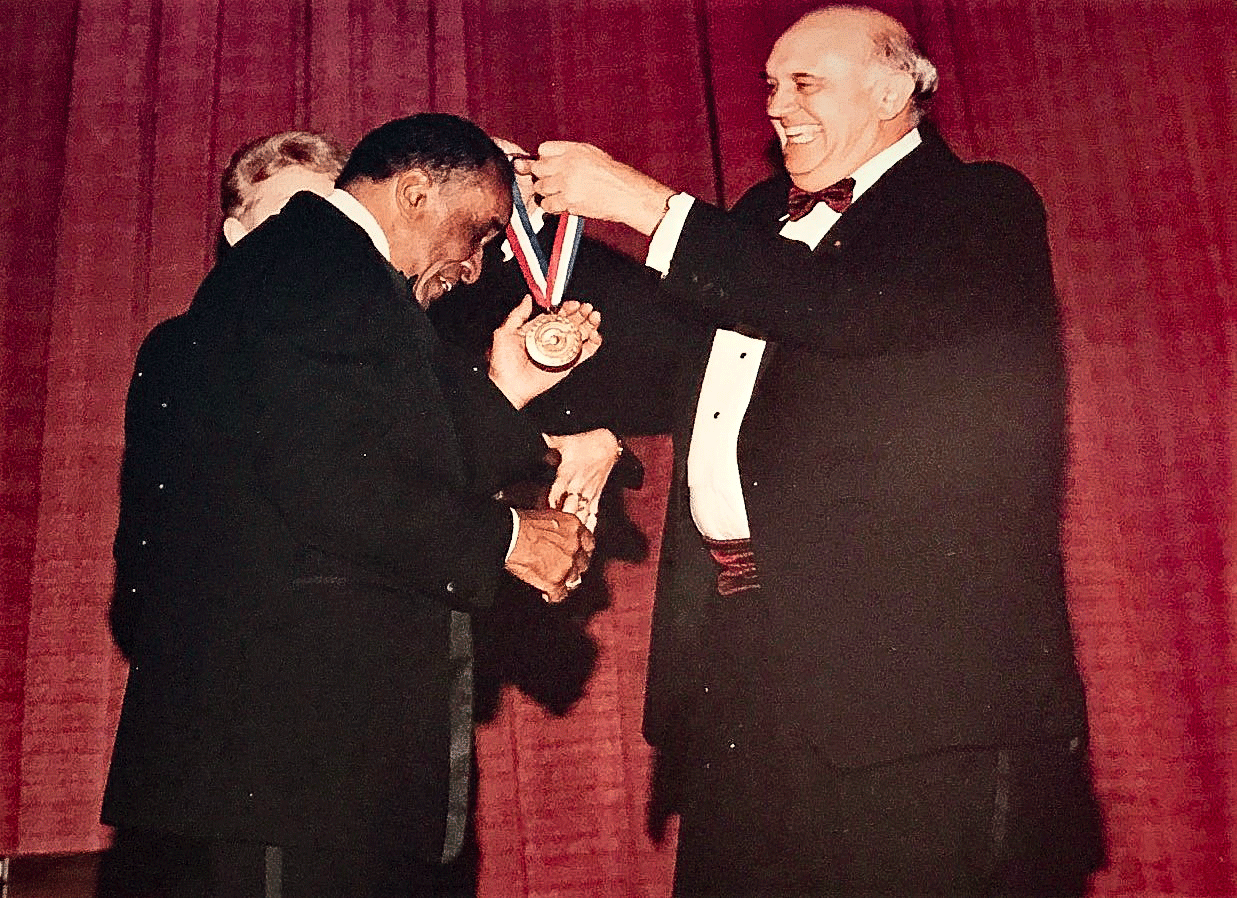

John Blanton Sr. during his induction into the GE Aviation Propulsion Hall of Fame by then-CEO Brian Rowe. Image credit: GE Aviation.

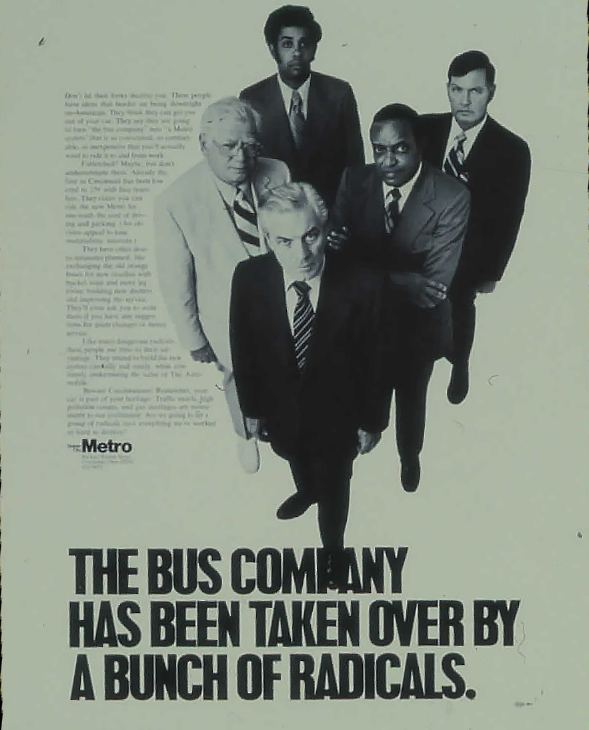

John Blanton Sr. during his induction into the GE Aviation Propulsion Hall of Fame by then-CEO Brian Rowe. Image credit: GE Aviation. John Blanton Sr. (right middle) in a 1970s advertisement for the Queen City Metro. Blanton worked for 26 years at GE Aviation, developing a reputation as a pioneer, an innovator and a risk-taker. Image credit: GE Aviation.

John Blanton Sr. (right middle) in a 1970s advertisement for the Queen City Metro. Blanton worked for 26 years at GE Aviation, developing a reputation as a pioneer, an innovator and a risk-taker. Image credit: GE Aviation.