This story is a collaboration with Biography.com.

The village of Amityville, New York has a rich and robust history.

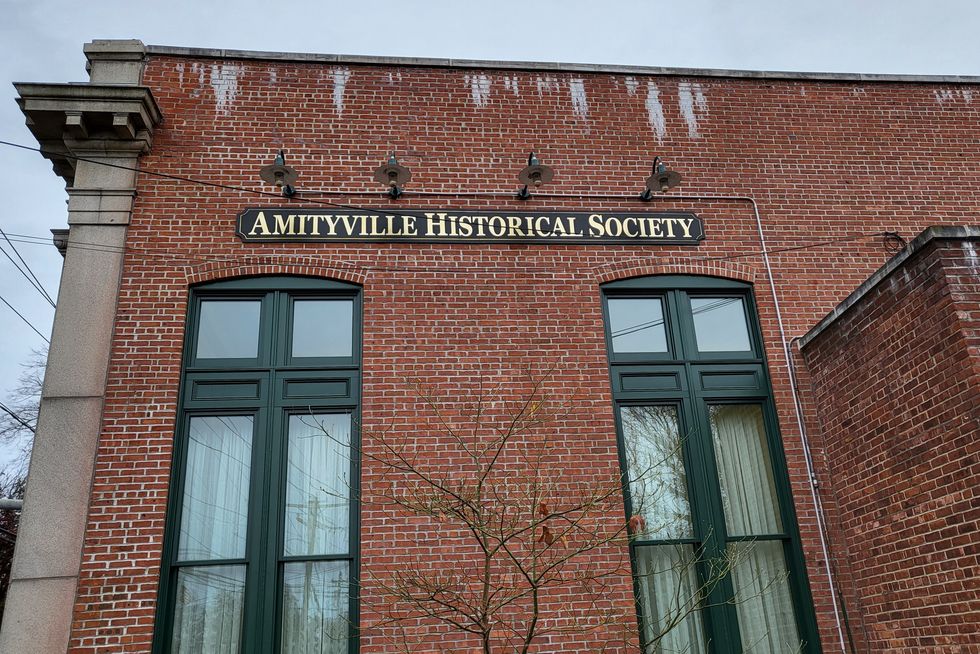

Peruse the halls of the Amityville Historical Society's Lauder Museum and you'll see playbills and movie tickets related to the many stars who once called Amityville home (a section in William T. Lauder's Amityville History Revisited boasts names like Annie Oakley and Will Rogers). You'll spot an Amityville flag that astronaut Kevin Kreger brought to space and back. And you'll even find remnants of a building that George Washington once visited.

But unless you're an Amityville native, you probably only know the town for its more sinister claim to fame—one that the Amityville Historical Society doesn't care to talk about. You won't find any macabre memorabilia about it within the Lauder Museum.

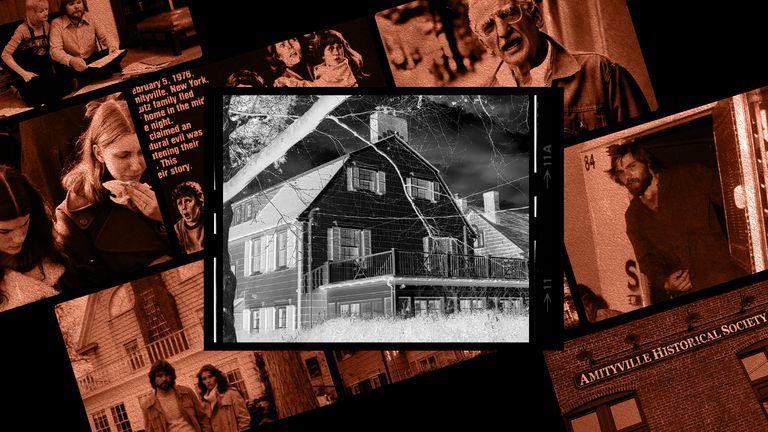

It's the so-called "Amityville Horror": a brutal murder, followed by claims of a haunting, made into a Hollywood movie, that forever immortalized Amityville, New York as the home of an infamous haunted house.

What Are the Origins of the Amityville Horror?

In the first chapter of 1973's A Brief History of Amityville, William T. Lauder asserts that "Amityville history might, in some respects, be said to have started at the beginning of time." But how far back do we have to go to find the source of the curse, literal or figurative, that has hung over Amityville for decades?

To the night when Ronald J. DeFeo Jr. killed his family? To the day when the Ocean Avenue house was built on what the Amityville film franchise claims was "Indian burial ground"?

It could be argued that the origins of the "Amityville Horror" phenomenon can actually be traced back to two particular points, all the way back in the 1890s.

Paris, December 1896: The filmmaker Georges Melies releases a 3-minute short entitled Le Manoir du diable, known in the U.S. as The House of the Devil. The brief pantomime shows the Devil arriving at his home in the form of a bat, before two cavaliers enter. The Devil uses tricks to try and chase the two men out of his home. Though he succeeds in scaring one of the men, the other ultimately brandishes a crucifix, which defeats the Devil and ends the film.

Le Manoir du diable is the first-ever haunted house movie.

Two years prior, across an ocean, at Thomas Edison's Black Mariah studio in West Orange, New Jersey, filmmaker William K. Dickson was documenting two dances performed by members of the Sioux nation. Filmed on the same day, the 16-second Buffalo Dance and 21-second Sioux Ghost Dance would prove to be, in the estimation of Edison film historian C. Musser, "the American Indian's first appearance before a motion picture camera."

But this was no "filmed at a distance" ethnographic film like the kind that would become more prevalent in the latter half of the 20th century. These men, listed as Last Horse, Parts His Hair, and Hair Coat, amongst others, were performers in Buffalo Bill's Wild West show, a massively popular traveling show of the day, and their dances were a part of their performance therein.

As PBS notes regarding Buffalo Bill's fabulist reenactments, "the show's depictions of Indians reinforced an inaccurate notion held by white Americans," namely that "the Indians were always the aggressors—attacking wagon trains, settlers' cabins, and Custer's forces." So while these films are the first to feature American Indian performers, they are just as crucially the first films to view indigenous people through a white man's lens, both figuratively and literally so.

Within these two shorts, which are nearly as old as the village of Amityville itself (incorporated on March 3, 1894), are two celluloid seeds that would grow and graft together into what became the "Amityville Horror."

Because the "true" story of the Amityville Horror is really the story of three mid-century movies.

Movie #1 That Made the Amityville Horror: Castle Keep (1969)

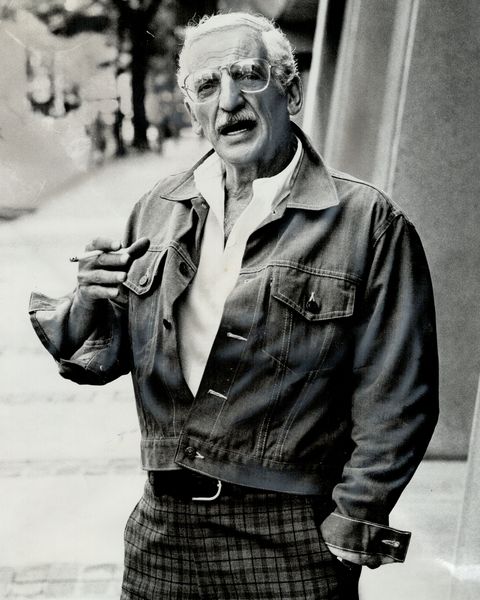

Castle Keep, a surrealist war film starring Burt Lancaster and Peter Falk, came and went fairly quickly in the summer of 1969. It was a box-office flop, and was quickly overshadowed by director Sidney Pollack's next feature, They Shoot Horses, Don't They?, a financial success that received nine Oscar nominations when it was released just a few months later.

Castle Keep was in line with the films of 1969 in terms of transgressive filmmaking, but hardly stood out from the crowd. It's sexual, but not nearly as sexual as that year's Best Picture-winning Midnight Cowboy. And it's violent, but not nearly as violent as that year's blood-soaked The Wild Bunch.

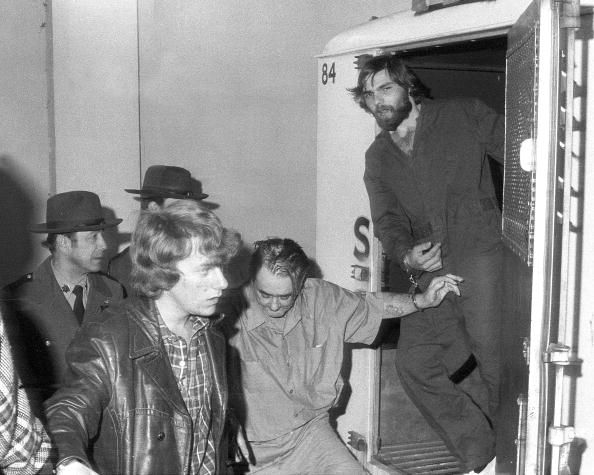

In fact, it is entirely possible that Castle Keep would have slipped completely from the public consciousness were it not for a single piece of trivia: As the story goes, on November 13, 1974, 23-year-old Ronald J. DeFeo Jr. watched the film Castle Keep on television. Then, as Biography notes, DeFeo took a .35 Marlin rifle and killed his entire family in their home at 112 Ocean Avenue in Amityville, New York. Every family member except for eldest sister Dawn was killed lying face down in their beds. (There are discrepancies regarding the manner of Dawn's death.)

Did the movie make him DeFeo it?

No. After all, as they would say two decades later in 1996's Scream: "Movies don't create psychos. Movies make psychos more creative."

But it's entirely possible that the reason we know what film he watched is because, at one time or another, DeFeo wanted people to think that. Just like he wanted people to think it was the mafia that framed him. Or his sister Dawn. Or, in the most popular version of events, he "heard voices urging him to kill his family." As Biography notes, up until his death in 2021, DeFeo "changed his story multiple times."

The reality is, it wasn't the images on the TV screen, nor the voices from the walls of the Amityville house, that caused DeFeo to kill. It was the home that Ronald Sr. had cultivated within those walls. Biography describes car salesman Ronald Sr. as a "domineering authority figure" who "engaged in hot-tempered fights with his wife and children," with Ronald Jr. (nicknamed "Butch") receiving the brunt of the abuse.

Butch's trauma would manifest itself in violent outbursts, which his parents tried to quell with therapy, and later, expensive gifts (like a "$14,000 speedboat"), and Butch himself would try to treat by self-medicating with LSD and heroin. But the urge to hurt remained. Biography describes one incident wherein Butch "attempted to shoot his father with a 12-gauge shotgun during a fight between his parents. DeFeo pulled the trigger at point-blank range, but the gun malfunctioned."

The inciting incident for the murder, rather than anything supernatural, may have been financial. The Biography profile for DeFeo makes note of a particular incident during Butch's employment at the family car dealership that preceded the infamous early morning massacre:

"In 1974, DeFeo, feeling irritated by what he believed a meager salary, plotted methods for embezzling money from the car dealership. In late October, the dealership entrusted him with the responsibility of depositing more than $20,000 to the bank. DeFeo planned a mock robbery with a friend, agreeing to split the money evenly with his accomplice. The plan went off without a hitch until police came to the dealership to question him. Instead of calmly answering the officers' questions, DeFeo exploded into rage. When police, suspicious that DeFeo was lying, asked him to come into the station to check out mug shots of possible suspects, he refused to comply. Ronald Sr. began to suspect that his son had committed the robbery. But when he questioned his son about his lack of cooperation with police, DeFeo threatened to kill his father."

On November 13, 1974, after committing the murders, DeFeo went to work at the car dealership. Twelve hours later, he pretended to "discover" his murdered family. Suffolk County police arrived, and DeFeo offered up an array of alibis before eventually admitting his guilt. "Once I started, I just couldn't stop," he said. "It went so fast."

Had that been the only occurrence of note at 112 Ocean Avenue, it's possible DeFeo's claim of "watching a violent movie" would have been the myth that some would have built around why he did it. Or perhaps, with his scruffy visage recalling that of Charles Manson, they would have leaned into blaming it on the LSD.

But a certain film came out the year prior, turned into a cultural phenomenon, and offered Americans of all stripes a different kind of alibi:

"The Devil made me do it."

Movie #2 That Made the Amityville Horror: The Exorcist (1973)

"I'm the Devil, I'm here to do the Devil's business"

On August 9, 1969, while Castle Keep dwindled in cinemas across the country, Charles "Tex" Watson uttered that phrase in a house on 10050 Cielo Drive in the Benedict Canyon neighborhood of Los Angeles. The "business" that Tex ascribed to "the Devil" was the brutal murder of the five people at the home that night: Sharon Tate, Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger, Wojciech Frykowski, and Steven Parent.

While this shocking and brutal act at the tail end of the 1960s made the "counterculture = satanic" connection easier for pop culture pontificators of the time, the Devil had already reentered the cultural lexicon in a big way one year earlier, due in large part to a film directed by Tate's husband, Roman Polanski.

That film, Rosemary's Baby, revolves around a young woman in New York City who finds that she has been impregnated by a Satanist cult, and her baby will be the Antichrist. The film, despite its taboo topic, became the 7th highest grossing film of 1968. It also received an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for Ruth Gordon, and a nomination for its screenplay.

Rosemary's Baby, along with the Rolling Stones' satanic-themed single "Sympathy for the Devil" that same year, and the "Tex" Watson quote, all captured a sentiment in the late 1960s and early 1970s that author Joan Didion would later describe in her essay The White Album as, "This mystical flirtation with the idea of 'sin'–this sense that it was possible to go 'too far,' and that many people were doing it."

More significantly, all of these things laid the groundwork for a film that is crucial to understanding not just the Amityville Horror phenomenon, but the rise of the Moral Majority in the late 1970s and the "Satanic Panic" of the 1980s.

William Friedkin's 1973 film The Exorcist, based on the 1971 novel by William Peter Blatty, was a cultural lightning rod like no other. Films had addressed America's anxiety about the late 1960s counterculture from a practical policing perspective in films like Dirty Harry and Electra Glide in Blue. They depicted a conflict between youthful rebellion run amok and the firm, harsh hand of the law. But those films also suggested to the parents in the audience that their long-haired hippie kids they didn't understand were criminals deserving of prison, or even death.

The Exorcist offered a different explanation. A spiritual explanation. Just like Regan, the little girl who goes from sweet to sacrilegious, your child's actions aren't their own: they're simply possessed by Satan. And though not as pronounced as later films would be, within The Exorcist is an undercurrent of "declining moral values" as the cause of the possession.

Regan is a child of divorce (California Governor Ronald Reagan had signed the country's first "no-fault divorce" in 1969), and the one film in which we see Regan's actress mother (played by Ellen Burstyn) acting involves campus student protests. (May 1970 had seen six student protestors killed by police and National Guard on the Kent State and Jackson State campuses.) As author Stephen King later noted in his 1981 book Danse Macabre, The Exorcist was:

"...a finely honed focusing point for that entire youth explosion that took place in the late sixties and early seventies. It was a movie tor all those parents who felt, in a kind of agony and terror, that they were losing their children and could not understand why or how it was happening."

But unlike Rosemary's Baby, and more in line with Melies' Le Manoir du diable, The Exorcist also offered audiences a "good guy" who could battle the villainous Devil—a spiritual equivalent to the cops beating back the hippies on episodes of McCloud or Adam--12. (Though The Exorcist does have a cop character in the form of Lee J. Cobb's Lieutenant William F. Kinderman.)

Those heroes are the clergy, Jesuit psychiatrist Father Damien Karras, and Irish Catholic archaeologist Father Lankester Merrin. Through these men, audiences were offered a solution to the supposed spiritual sickness they had been feeling and fearing by the early 1970s: leave behind the hippie ways, return to the Church. Film critic Pauline Kael went so far as to call The Exorcist "...the biggest recruiting poster the Catholic Church has had since the sunnier days of Going My Way and The Bells of St. Mary's."

Despite its graphic content, and some condemnation from the clergy, The Exorcist was the #1 film at the 1973 box office, beating out the #2 film, The Sting, by nearly $10 million. (Another Satan-themed film, the X-Rated The Devil in Miss Jones, was also the 10th highest-grossing films of 1973.) In a rarity for horror films even today, The Exorcist received 10 Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, and won an Oscar for its screenplay.

A wave of fellow Catholic-tinged, counterculture-combating horror films emerged in the wake of The Exorcist, like The Omen and The Sentinel. But perhaps the story most indebted to The Exorcist is that of the "Amityville Horror," which is why it's not surprising to discover that the author of The Amityville Horror had a connection to the making of The Exorcist.

Before Jay Anson wrote his bestselling "based on a true story" book The Amityville Horror, he told The New York Times, "I had never even tried a book before." What Anson had done was produce "making-of" featurettes for films like Klute and Deliverance. According to what he told The New York Times in 1978, Anson had no familiarity with the occult until he was commissioned to work on such a "making-of" featurette for The Exorcist.

Working on this, "...he became friendly with the film's technical consultant, Father John Nicola, the Roman Catholic Church's occult investigator in America." The two pitched a book about exorcisms to publisher Prentice‐Hall. Though the Nicola book never came to fruition, Prentice-Hall would soon contact Anson to take on another story: that of the Lutz family.

As Biography notes, only 13 months after Ronald "Butch" DeFeo had killed his family on the home at 112 Ocean Avenue in Amityville, "...the Lutz family purchased the home at a drastically reduced price of $80,000 (due to the murders) but only lasted 28 days before leaving it."

As Anson's eventual The Amityville Horror stresses, money was tight for the Lutz family. The home was out of their budget even at $80,000 (they were looking for a place under $50,000), and they tried to save additional funds by also purchasing many of the home's furnishings left behind by the deceased former owners, including the beds in which they died, for another $400.

Biography also notes the supposed supernatural happenings the Lutz family claimed to have encountered during their brief occupancy at 112 Ocean Avenue included "green slime oozing out of the walls" and experiencing "cold spots in certain areas of the house," as well as an abundance of flies plaguing the home.

The Lutz family also claims that their local priest, Father Pecoraro, visited the home to bless it, heard a voice say "Get out!," and "told the Lutzes to never sleep in that particular room in the house." For his part, the real Father Pecoraro swore in an affidavit that he had little connection with the Lutz family, never visited their home, and had spoken to them only once by telephone.

Anson's eventual book on the Lutz case, the 1977 novelistic The Amityville Horror, would take some artistic license with the story, adding some cinematic flair, likely drawing from the massively successful film Anson had first been commissioned to make a "making of" for. It quickly became a best-seller, and fittingly was snapped up by Hollywood to become a major motion picture—one that would put Amityville on the map for reasons the town wish had stayed uncharted.

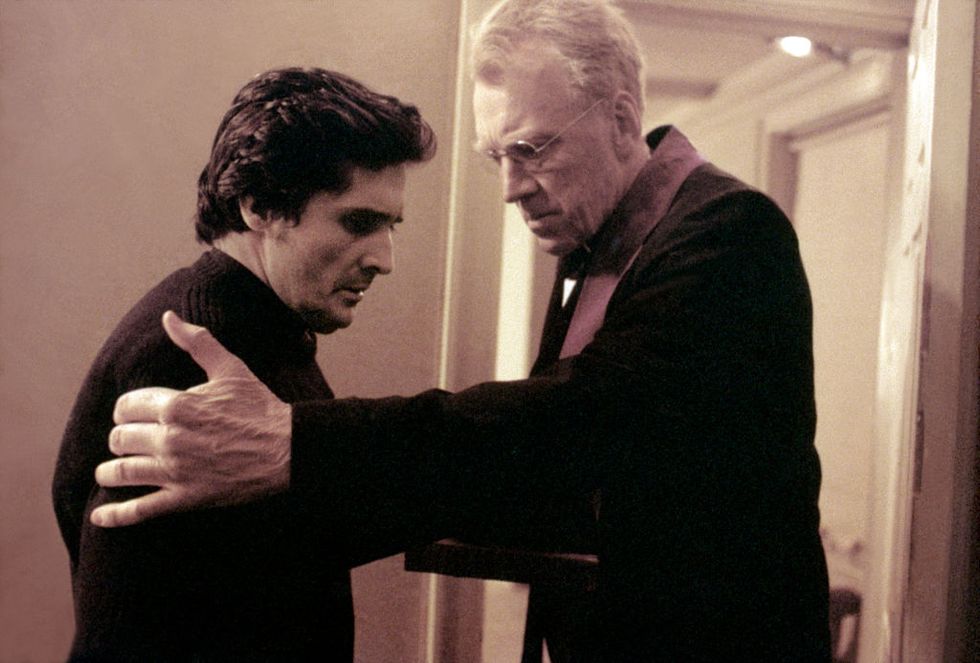

Movie #3 That Made the Amityville Horror: The Amityville Horror (1979)

Director Stuart Rosenberg had, once upon a time in 1967, directed Paul Newman in the critically lauded classic Cool Hand Luke, a film with both theological and countercultural themes. But by the mid-1970s, Rosenberg was in a rut. His 1975 reteaming with Paul Newman, The Drowning Pool, was a box-office disappointment that had The New York Times declaring his direction "muscular but pedestrian." His follow-up, Voyage of the Damned, got three Oscar nominations but was an inarguable flop, earning only $1.75 million.

Rosenberg needed a hit for his next picture. And he got one, by way of Anson's The Amityville Horror novel. The book wasn't just a bestseller; it also had the benefit of being "based on a true story," while having the cinematic narrative propulsion Anson added through his years of experience in the film industry.

Anson's novel, for example, turned the tangential involvement of Father Pecoraro into the fictional heroic figure of the work, Father Mancuso, who is much more involved with the saga of the Lutz family and their haunting than the real Father Pecoraro was ever alleged to have been.

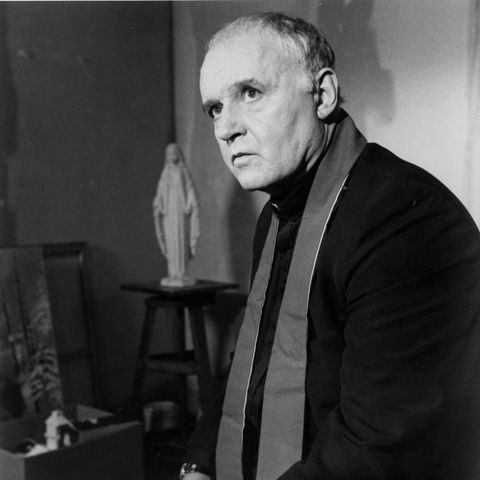

Beset upon by illness after his encounter with the haunted home, Mancuso is even paired with a law officer, just like the priests in The Exorcist, in this case the character of Suffolk County Sergeant Gionfriddo. The film also clearly felt the priest was a crucial part of the story, casting Academy Award-winner Rod Steiger as Father Francis 'Frank' Delaney.

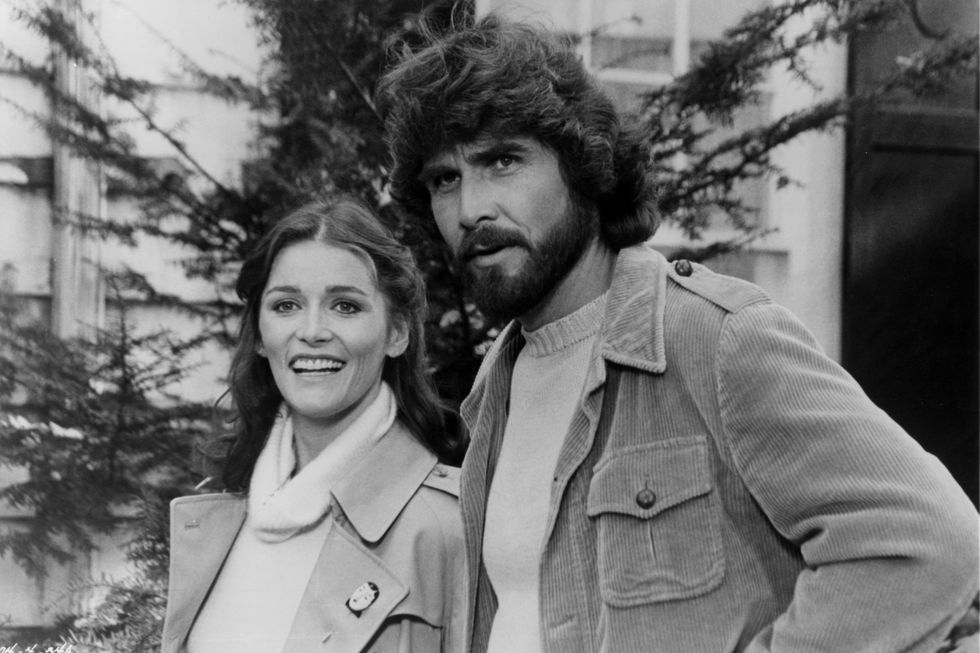

For the Lutz family, actor James Brolin was cast in the role of George, while Margot Kidder took on the role of Kathy. In promoting the film, both Brolin and Kidder claimed to have also experienced strange occurrences on set pertaining to the supernatural, but those were contrived. Kidder would later say in a 2005 interview, "When we did Amityville, the producers told us we should say all these terrible things happened on the set. It was all bull****. Nothing happened, but it was funny."

But while the actors who played the Lutz family have admitted to fabricating the hauntings they once claimed to experience, the real George and Kathy Lutz maintained that it was all true. Biography notes that the couple "took a lie detector test to prove their innocence," and that they passed the polygraph. Son Daniel also "claims the house ruined his life and that he continues to have nightmares to this day."

But in 1979, attorney William Weber, who represented Ronald "Butch" DeFeo, came forward with a claim that not only said the Lutz family contrived the entire haunting, but that he was an instrumental part of its creation. Trying to reopen the case and have DeFeo plead insanity, Weber claimed to have approached George and Kathy with the idea that, if they also claimed to experience strange things in the house, they could get a book deal and the story could aid his client's case.

Weber claimed the trio contrived the entire story of the haunting and all its elements "over many bottles of wine." But when either motivated by cutting Weber out of any potential profits, or simply being concerned that any money Weber made would be shared with convicted killer DeFeo, the Lutz family allegedly cut ties with Weber and pursued a book deal on their own.

Whatever the truth, the embellishments all proved profitable. The Amityville Horror became the second-highest grossing film of 1979, outgrossing Alien, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, and Rocky II (Best Picture winner Kramer vs. Kramer was the only film to beat it out at the box-office.) Composer Lalo Schifrin's score for the film even earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Score.

The film also spawned one of the more robust quasi-franchises in film history. Beyond the direct sequels like Amityville II: The Possession and Amityville 3-D, and the 2005 Ryan Reynolds-led remake, there have been more than 30 films that have loosely mined the "Amityville Horror" story for their own means, from Amityville: The Awakening and The Amityville Asylum to Amityville Karen and Amityville in Space. There have been so many Amityville films that the 2023 Fangoria Chainsaw Awards had to create a specific category for Best Amityville. That's because, as Paste Magazine points out:

"Because Amityville is a real New York town, and because the DeFeo murders—and, I guess, the Lutz family moving in and then out, regardless of their transparent attempts to cash in on claims of ghosts and ghoulies—were all documented in the public record, they couldn’t be contained as alluring intellectual property except under the specificities of Anson’s book."

But while the glut of unauthorized Amityville sequels keeping the "Horror" in the public consciousness are certainly irksome to the residents of Ocean Avenue and the historians in Amityville, it's a specific invention of Anson's book that has arguably had the most significant impact on both the town and American pop culture at large.

The Amityville Horror: Those Who Remain

The most pernicious, and provable, fabrication from Jay Anson can be found in Chapter 11 of The Amityville Horror. The book claims that George Lutz (changed to Kathy in the film) spoke to the Amityville Historical Society, which informed him that the "very location of his house" had a troubling past:

"It seems the Shinnecock Indians used land on the Amityville River as an enclosure for the sick, mad, and dying."

The book then alludes to a settler named John Catchum, or Ketcham, who was apparently buried on the property after being forced out of Salem, Massachusetts "for practicing witchcraft."

While Anson's book does specify that the land was not used as a Shinnecock burial ground "because they believed it to be infested with demons," the conflation in the public consciousness of Shinnecock ground and Ketcham burial makes The Amityville Horror the inception of one of the most troubling tropes of contemporary horror: the Indian Burial Ground. This trope was solidified later in Stanley Kubrick's 1980 adaptation of Stephen King's The Shining, which contains the line "The site’s supposed to be on an Indian burial ground."

The cliche became so pervasive that people tend to ascribe it even to stories that don't contain that element. (Poltergeist, for example, never actually uses the Indian Burial Ground trope, though people often falsely remember it doing so.) And your average Long Island resident will readily tell you that "everybody knows" the Amityville house as "built on Shinnecock burial ground."

Except ... it wasn't. And we know this, because the Shinnecock never occupied that particular patch of land. As film critic and citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma Shea Vassar noted in their column Through a Native Lens for Film School Rejects:

"All land is Native land, but the Shinnecock tribe never occupied the area on which this infamous house was built. I mean, if you’re going to use a specific nation, then at least name the correct one. The erasure and inaccuracies of Native cultures within the movie industry are made worse by mixing up the names of our communities."

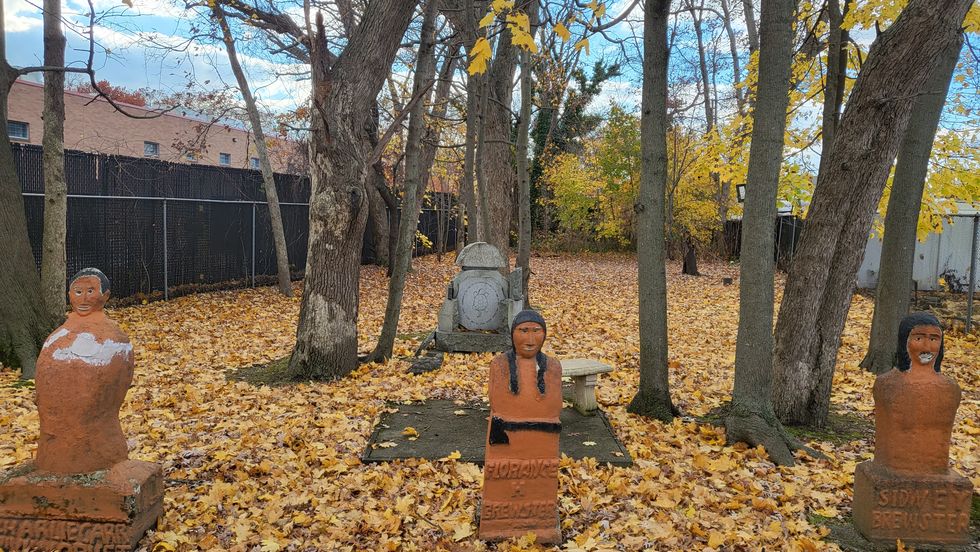

There are, however, indigenous burial grounds in the area of North Amityville, within the town of Babylon. Visitors to nearby Copaigue can find two such sites, one on either side of Bethpage Road. The Brewster Burial Grounds and Green Bunn Burial Grounds were designated by Babylon in 1994, according to the town historian. Within each is a small stone memorial depicting a turtle, which were erected in 1995. On the Brewster Burial Ground, there are also three statues devoted to specific members of the Brewster family that had been erected in the 1950s by a descendant.

But while these burial grounds are recognized and preserved, others are the subject of contentious conflict to this day.

Despite Amityville being falsely infamous for a house "built on Indian burial ground," as recently as 2021, Newsday reports, a developer was attempting to start a condominium project in North Amityville, on ground it has been asserted "may contain native remains." While the town of Babylon approved the development, noting it had "conducted its own review," the state of New York intervened and has "recommended a phase 1 archaeological survey."

The effort to preserve the site was led by Sandi Brewster-Walker, the executive director of the Montaukett Indian Nation. Indeed, the land that Anson's book claimed was used by the Shinnecock would have actually been occupied by a Western cluster of the Montaukett.

If you find yourself in Amityville, there will naturally be a temptation to visit the house on Ocean Avenue. It's still there, though it has been remodeled, removing its infamous rounded windows, and it has had its address changed to deter tourists. "No Parking" signs prevent visitors from even stopping their vehicle in front of the residence.

Truthfully, someone looking for an "old house" in Amityville would in fact be better served traveling further up Ocean Avenue, to Nautical Park, where a well-worn historic home awaits restoration. On a recent visit, a local resident informed PopMech that several people have mistaken the dilapidated building for the infamous "horror house."

Of course, those curious about Amityville history can visit the actual Amityville Historical Society. You'll find antiques and memorabilia from decades of very real history from the village of Amityville. Stand on the steps of that museum, and you can see the site of the St. Mary's Chapel, built in 1888 by Wesley Ketcham (the real Ketcham legacy in Amityville). Glance down Albany Avenue, and you can see Colored School #6, which the Amityville Record notes "was one of the Island’s first schools to be desegregated," thanks to the efforts of Charles Devine Brewster, an ancestor of the aforementioned Sandi Brewster-Walker.

There's one last piece of Amityville history that is worth seeking out. It's a testament that dates back before The Amityville Horror, before Castle Keep, before even the films of Dickson and Melies.

Since December 2021, on the corner of six streets in North Amityville, one can find heritage designation markers displaying the Montaukett Tribal Nation logo. These signs signify recognition of the descendants of the Montaukett that lived on that Amityville land for thousands of years prior to the arrival of Europeans settlers and Dutch traders.

These signs read, "Montaukett Nation. We Are Still Here!"

Michael Natale is the news editor for Best Products, covering a wide range of topics like gifting, lifestyle, pop culture, and more. He has covered pop culture and commerce professionally for over a decade. His past journalistic writing can be found on sites such as Yahoo! and Comic Book Resources, his podcast appearances can be found wherever you get your podcasts, and his fiction can’t be found anywhere, because it’s not particularly good.