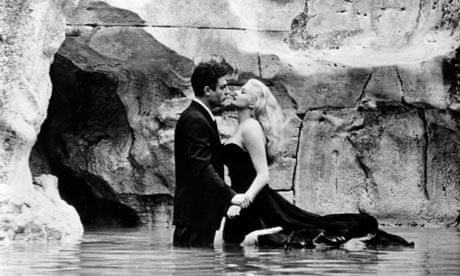

In glamorous Rome, Fellini's La Dolce Vita was the box-office hit of 1960, and launched Marcello Mastroianni as an international heart-throb. No film captured so vividly the flash-bulb glitz of Italy's postwar "economic miracle". After the drawn-out trauma of fascism, the nation was poised for a consumer boom of televisions, fridges and Fiat 500s. Daringly, Fellini disavowed the neo-realism of films such as Bicycle Thieves for the stylised fantasies of Hollywood. The Vatican not surprisingly objected to the scene in which Mastroianni makes love to Anita Ekberg in the waters of the Trevi fountain, and tried to have the film censored. Ever since, says the historian Stephen Gundle, Rome has endured as a fantasy of the "sweet life".

Yet all was not well behind the roseate flush of Italy's newfound prosperity. The miracolo italiano had failed to extend to the deep south, the "other Italy", where there was poverty. In search of a consumer idyll, southerners began to arrive in Turin and Milan with their cardboard suitcases, only to face abuse. The wretchedness of these migrants was its own indictment of Italy's vaunted economic renewal. For all its surface frivolity, La Dolce Vita hinted at deepening social unease. In the film's extraordinary closing scene, drunken party-goers stare at a grotesque sea beast netted on a beach outside Rome; a single glaucous eye stares accusingly at them. In Gundle's analysis, the "dead sea monster" alludes to the Montesi affair, the great scandal of 1950s Italy, and the unacknowledged inspiration for Fellini's movie.

Death and the Dolce Vita, a hybrid of history and police detection, brilliantly recreates the details of the Montesi affair and its sordid aftermath. On 9 April 1953, a woman's body was found washed up on a beach near Rome, clothed except for shoes, skirt, stockings and suspender belt. The 21-year-old Wilma Montesi had gone missing from her family home in Rome 36 hours earlier. The police verdict of accidental death by drowning was overturned by journalists, Gundle relates, who insisted that Wilma had not gone for an afternoon swim in Ostia after all. Instead she had gone to a swish hunting lodge in nearby Capocotto, where wild, Felliniesque orgies were hosted by a right-wing Italian aristocrat embroiled in drug crime and Italy's kickback and bribery culture. Drugged and abused, Wilma was dumped on the sands at Ostia and left to die.

In the trial that ensued, neither the playboy aristocrat suspected of the murder, Ugo Montagna, nor his presumed accomplice, Piero Piccioni, was arraigned on any kind of charge. Piccioni, the son of Italy's deputy prime minister, appeared to be protected by cabinet ministers and members of the gutter press as well as by corrupt police officers and their gangland associates. Seven years had passed since the Italian republic was founded in 1946, yet the hopes for a fairer, better Italy had not been met. To this day those involved in Montesi's death have evaded justice. The public insisted that shadowy cliques and mafia cabals lay behind the sordid crime.

Italy is, notoriously, a land of hydra-headed conspiracy theories, and it was not long before Montagna was exposed as a Sicilian of dubious aristocratic credentials, who consorted with mobsters and larcenous power-brokers in Italy's ruling Christian Democrat party. Piccioni himself, an aspirant jazz composer, turned out to be romantically attached to the screen actor Alida Valli, who had starred in The Third Man (and was rumoured to have been a lover of Mussolini). Even after the Montesi case was officially closed, the police dossiers continued to swell, creating a climate of suspicion and unease in the Italian capital. In September 1954, the government was brought to the brink of collapse when Piccioni's father, Attilio, was forced to resign.

In pages of punchy prose, Gundle recreates 1950s showbiz Rome with its prostitutes, paparazzi and tawdriness. Many of the MGM blockbusters of this period – Ulysses, Helen of Troy – were shot there. The actor Marina Berti (whose English mother, Gladys Melrose, had taught the teenage Primo Levi in Turin in 1939) starred alongside Robert Taylor in Quo Vadis. Wilma Montesi, a carpenter's daughter, wanted only to be like Berti and the tinseltown starlets who visited from Hollywood. Like the young Fellini himself, in fact, she adored Mae West and the "impossible whiteness" of Jean Harlow's skin. Soon she was out of her depth in a demi-monde of narcotics, hoodlum financiers and sugar-daddy politicians. As a saga of ill-gotten money and mink, the Montesi affair foreshadows the "bunga bunga" parties of the Italian prime minister today. As well as being a thriller, Death and the Dolce Vita provides an excellent account of the virtues and misdeeds of Europe's most foxy political class.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion