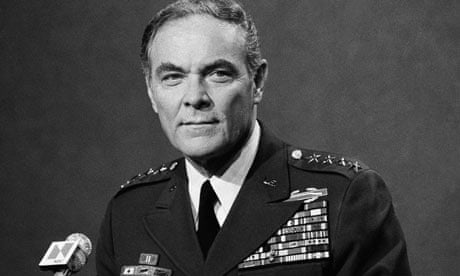

The record books say that America has only ever had one unelected president in its history: congressman Gerald Ford. But General Alexander Haig, who has died aged 85, might well rate as a second. He never faced an electorate in his life, but he ran the White House almost in secret during the 15 months up to President Richard Nixon's resignation in August 1974 – taking over the impetus of a paralysed presidency in a manner that, however necessary under the circumstances, was barely constitutional.

His second period at the highest levels of government came as secretary of state for the first year and a half of Ronald Reagan's presidency, from January 1981. Two themes preoccupied his brief tenure of the post: the ferocious bureaucratic battles that marked the Reagan administration and Haig's obdurate belief that communism was baying at the gates of the US. The Democratic speaker of the House of Representatives, Tip O'Neill, said: "Haig hadn't been secretary of state more than three weeks when he told me over breakfast that we ought to be cleaning out Nicaragua."

Though he clearly did not understand it at the time, Haig's poorly hidden presidential ambitions were scuppered in those early days with his lamentable performance after the assassination attempt on Reagan in March 1981. Amid the inevitable confusion, the secretary of state burst into the White House press room to declare, when a reporter asked who was making the decisions: "As of now, I'm in control here in the White House."

He later said that at the moment he was asked, he was technically right. But his apparent ignorance of the constitutional lines of power left an abiding impression of impetuousness and arrogance, all the greater for being caught on television. When he did run as a Republican hopeful for the White House in 1988, he rated just 3% in the opinion polls.

While Haig's preoccupation with Central America had a greater long-term impact on America's internal and foreign politics, the greatest crisis he faced at the state department was the 1982 Falklands war, in which he tried unsuccessfully to act as mediator, flying to both London and Buenos Aires in the process. There was probably little chance of success, but his efforts were seriously undermined by undisguised support for the Argentinians from the US ambassador to the UN, Jeane Kirkpatrick.

In his memoirs, Haig commented: "The war was caused by the original miscalculation on the part of the Argentinian military junta that a western democracy was too soft, too decadent to defend itself. This delusion on the part of undemocratic governments has been, and remains, the greatest danger to peace in this century." But his failure to avert the conflict, as he also conceded, "ultimately cost me my job as secretary of state".

His reign had been marked by ferocious battles, set out in loving detail in his memoirs, over bureaucratic turf with Reagan's kitchen cabinet. However, even Haig's well-honed skills were inadequate on this field, and he lost the fight in June 1982, when Reagan handed him a letter accepting his resignation. Since Haig had not actually offered it, he got to work on a draft. It was still not complete when he heard the president announce his departure on television.

The pattern of Haig's life was set early. Born and brought up in Bala Cynwyd, one of the classier suburbs of Philadelphia, he was the middle child of a prosperous lawyer. But the family's comfortable life was shattered when his father died of cancer at the age of 38. Haig was then 10, and no more than average academically. He had gained a scholarship to a Roman Catholic preparatory school but did not do well. It was withdrawn after a couple of years and he transferred to a local high school.

Though his mother was keen he should follow his father's calling, he was intent on a military career. Confirming his headteacher's view that "Al is definitely not West Point material", his application to the US military academy failed. Then his uncle, who had been supporting Haig's mother and his siblings, intervened and in 1944 Haig scraped into the military college, situated to the north of New York, as an acknowledged political appointee. Under the stress of war, the four-year course for officers had been cut to three. The topics removed from the curriculum included English, social sciences and history, in all of which Haig later proved deficient.

He graduated from West Point in 1947, finishing 214th out of 310. His classmates shrewdly assessed him as having "strong convictions and even stronger ambitions". Haig opted for the cavalry and, after a year's training, was posted to the American occupation forces in Japan. Eighteen months into that posting he married Patricia Fox, the daughter of one of the top brass in Tokyo, General Alonzo Fox, and was then appointed the general's aide-de-camp. This brought the young lieutenant into the extraordinary military headquarters of General Douglas MacArthur, run more or less as an alternative court to Emperor Hirohito's.

The experience of MacArthur's megalomania left an indelible impression on Haig. He commented later that: "I was always interested in politics and started early in Japan, with a rather sophisticated view of how the military ran it." The outbreak of the Korean war also fixed his career-long belief that the communist enemy was always at the door. The initial North Korean assault in June 1950 was a disaster for US forces on the peninsula and brought home how ill-prepared MacArthur's command had become for its military role. Although Haig's unit was rushed to Korea and suffered heavy casualties, he did not go with it: instead, he was sent to accompany his father-in-law to Taiwan, on a liaison mission to Chiang Kai-shek.

When he was eventually assigned to the battle zone, it was as a military assistant on the headquarters staff of an old friend of his father-in-law's, General Edward Almond. MacArthur's selection of Almond as commander of US troops preparing to land in force behind the enemy's rear was later described as "an act of military nepotism".

Haig's role in the highly successful Inchon landings remained obscure, but the ensuing campaign led to the first of many controversial episodes in his military advance. During the battle for Seoul, Haig was awarded a Bronze Star for bravery during a crossing of the Han River. The official citation referred to his outstanding heroism. However, the later official history of the crossing said there had been "no enemy resistance" and that the North Korean positions were "lightly manned". Almond had recommended the decoration for his assistant and later awarded him two further Silver Stars for flying over enemy positions.

Haig left Korea as a captain in 1951, suffering from hepatitis. In 1953 he was appointed to the staff of West Point as a disciplinary officer, remembered for his obsession with spit and polish, and was then assigned to a tank battalion with the American forces in Europe. He gained a routine promotion to major and, redeployed to the European Command headquarters in Germany, had his first experience of diplomacy.

Congress had been grumbling about the cost of maintaining the US presence in Germany, and Haig took part in the 18-month negotiations to persuade the West Germans to shoulder more of the burden. This brought him another medal for "remarkable foresight, ingenuity, and mature judgment".

It also seemed to increase his taste for the administrative and political aspects of military life. In 1959 he enrolled on a military staff course and then went on to a further course at Georgetown University in Washington, where American diplomats trained. The thesis for his Georgetown master's degree showed how his ambitions were developing. It spoke of the need for a new breed of military professional occupying a prominent seat among presidential advisers. It also gave an early glimpse of his tormented prose, with incomprehensible references to "interpretive vagaries" and "a permeating nexus".

Armed with these new qualifications, Haig was assigned to a staff position at the Pentagon, where his father-in-law had become deputy to the assistant secretary for international affairs. Though Haig's own job was in military planning, his presence at the defence department, allied to his family connections, pitched him into the tangled world of Washington's cold-war politics. The Cuban missile crisis of October 1962 erupted soon after his appointment, and he later claimed that it disillusioned him with the way the doctrine of flexible response was applied. "You never applied one iota of force," he commented. "I was against this. It provided an incentive to the other side to up the ante."

The key moment in Haig's career came in 1963 when he was picked to act as military assistant to Joe Califano, a lawyer in the army secretary's office. The army secretary was Cyrus Vance, and this period established personal and political connections from which Haig benefited for the rest of his public life. He seemed to sense that it was time to make his mark. When Vance was promoted to become deputy to the defence secretary, Robert McNamara, Califano and Haig floated up with him. Though Haig still held a relatively low-level job, he acquired considerable access both to information and to Washington's movers and shakers.

But the growing US involvement in the Vietnam war made it essential that any ambitious officer become directly involved in the fighting. In 1966 Haig was made operations planning officer for the First Infantry Division, stationed near Saigon and, in a war that saw 1,273,987 medals awarded to American troops, gained a Distinguished Flying Cross within a month of his arrival. Lightly wounded in the eye when a prisoner blew himself up, Haig was involved in a number of battles in which he gained two more DFCs and 17 Air Medals. Once again, there was a conflict between some of the citations and later official accounts of the incidents.

However, by the time he returned to America with the rank of colonel, in 1967, he was firmly established as a Vietnam hero. He went back to West Point to revive his reputation as a military martinet until in 1969, with Nixon the incoming president, he was recruited by the national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, to the National Security Council, recommended, as Kissinger noted in his memoirs, by Califano and McNamara. Haig, Kissinger continued, "soon became indispensable ... By the end of the year [1970] I had made him formally my deputy. Over the course of Nixon's first term he acted as my partner, strong in crises, decisive in judgment, skilful in bureaucratic infighting ... [But] I could not help noticing that Haig was implacable in squeezing to the sidelines potential competitors for my attention".

Among the crises in which Haig played a leading role was America's covert effort to overthrow the regime of Salvador Allende in Chile (1970-73). Haig was also cementing his relationship with Nixon and was party to one of the early manifestations of the White House's growing paranoia. In response to a number of leaks, the phones of 17 officials and journalists were tapped by the FBI. Haig helped select the candidates and, apparently aware of the doubtful legality of the operation, ordered that there should be no written record.

He was also closely involved in the aftermath of the massive leak in 1971 of the secret history of the Vietnam war, the Pentagon Papers, when the White House moved illegally against the man responsible, Daniel Ellsberg. This loyalty was rewarded by promotion to major-general in 1972 and, six months later, by appointment as vice-chief of staff of the army, raising him to full general and allowing him to leapfrog 240 more senior officers. He did not, however, remain long at the Pentagon.

As the revelations of the Watergate scandal began to accumulate, after the burglary of the Democratic party headquarters in Washington on 17 June 1972, Nixon was forced to sack many of the senior staff involved. On 30 April 1973, it was the turn of the White House chief of staff, HR Haldeman. The search for a successor was urgent. With the president obsessed with the scandal, the process of government was almost at a standstill. Haldeman, who had become friendly with Haig during the skirmishing over the Pentagon Papers, recommended him as an interim chief of staff, a suggestion bitterly opposed by Haig's recent boss, Kissinger. However, Kissinger could not offer an alternative, and Haig's appointment was duly announced on 4 May, to what turned out to be the most significant job of his life.

Since Haig never gave a substantive account of the 15 months he spent with Nixon, it is unclear if he arrived with a definite strategy in mind. The crisis threatened to pitch the three arms of government – the presidency, the Congress and the judiciary – into unprecedented conflict. In Haig's early weeks as chief of staff, he seemed to do little more than meet each development as it came along and fend it off as best he could.

The Senate hearings on the Watergate allegations had begun within two weeks of his appointment, with damaging testimony from the former White House counsel John Dean highlighting the president's direct involvement. Two months later came Alexander Butterfield's revelation of Nixon's all-embracing tape-recording system.

The president's refusal to hand over the tapes and his dismissal on 20 October 1973 of Archibald Cox, the special prosecutor who tried to force the issue, clearly signalled the beginning of the end for Nixon. The day after this action, 22 bills of impeachment were introduced into Congress. On 10 October, the ineffectual vice-president, Spiro Agnew, had resigned because of bribes he had taken while governor of Maryland, and was succeeded by Ford. From being an interim appointee, Haig moved more and more centre stage as chief of staff. Though it has not been clearly documented, there is strong evidence that he became functional president.

Kissinger commented that "by sheer willpower, dedication, and self-discipline, he held the government together". Leon Jaworski, who eventually mounted the dozens of Watergate prosecutions, had to work closely with Haig. He wrote that he was convinced that "Haig, not Nixon, was making the executive department of government function," and quoted Haig as saying: "I'm not trying to save the president. I'm trying to save the presidency." But Jaworski also thought Haig was intent on blocking the prosecutor's efforts to uncover the conspiracy.

Haig briefly stayed on at the White House under Ford and was widely believed to have played a crucial role in the decision to pardon Nixon – a misjudgment that cost Ford the 1976 election. Then Ford appointed him supreme allied commander in Europe, the top military job in Nato, from which General Andrew Goodpaster was precipitately removed to create the vacancy.

Haig's arrival in December 1974 was not popular: the Dutch foreign minister called it a public relations disaster. This feeling was compounded by Haig's casual revelation, before the West German government had been consulted, that an American brigade was to be stationed in the north of the country. He also got into hot water making political speeches against Eurocommunism and telling the Italians that communist participation in their government would be "unacceptable".

However, he gradually toned down his rhetoric to concentrate on narrower military issues, and his popularity in Europe increased. His term was extended for a further two years in the dying days of the Ford administration, and he then found himself coping with the vagaries of President Jimmy Carter's policy on the deployment of the neutron bomb in Europe. Haig threatened to resign when Carter changed his mind about deploying the weapon, but the dust gradually settled and he was given another two-year extension.

He later said that his principal achievement during his term was to secure a commitment from the 14 member governments to increase their military spending by a regular 3% a year to counter the Soviet bloc arms build-up. But he was becoming highly unpopular in Washington and was excluded from much of the debate about the Salt II strategic arms limitation agreement.

In January 1979, he announced his resignation. In June there was an attempt on his life when a bomb exploded near his car as he was travelling to the Nato HQ in Belgium. No group ever claimed responsibility. There was an assumption that he would run for the presidency, but he disclaimed any ambition at the end of the year and took over as president of United Technologies, a defence contractor. A few months later he had a double heart by-pass operation. As part of the standard wheeling and dealing of the American military-industrial world, he maintained contact with politicians of both parties, including Richard Allen, national security adviser to Reagan.

Partly through this connection he was asked to speak on foreign policy at the 1980 Republican convention and then began to be tipped as a likely secretary of state. With the election of Reagan, he was duly nominated, though the two men had only spent three hours together in their lives. After leaving the state department, Haig turned to business. From 1984 onwards, he put his experience to commercial use through the "strategic advice" offered by his firm Worldwide Associates, and as a commentator on Fox News. He became a director of various firms, including MGM, America Online and Compuserve.

Haig's principal skill – learned early in life – lay in playing the system to the full. Otherwise he was not very bright and extremely vain. If his major service was to help his country through its worst constitutional crisis, it was offset by the long-term consequences of his ill-conceived interventions in Central America.

He is survived by Patricia, a daughter and two sons.