Canadian police have announced the discovery of more human remains on a property frequented by Bruce McArthur, an alleged serial killer believed to have murdered at least eight men in Toronto’s gay community. A self-employed landscaper, McArthur allegedly buried the remains of some victims in flower planters. Most of his victims, all gay men, were recent immigrants of south Asian or Middle Eastern background. LGBT activists have accused the Toronto police of failing to take seriously years of reports of disappearances in the Toronto gay village.

The Guardian spoke with Peter Vronsky, a historian and journalist based in Toronto and the author of several books studying the history and psychopathology of serial killers. His latest, Sons of Cain: A History of Serial Killers from the Stone Age to the Present, will be released 14 August in the US and Canada and 16 August in the UK.

The book explores how our understandings of serial killers – called “monsters” before the advent of modern psychology – have changed over time, and considers answers to a difficult question: what, exactly, “makes” a serial killer?

One of the oldest questions in criminology – and, for that matter, philosophy, law, theology – is whether criminals are born or made. Are serial killers a product of nature (genetics) or nurture (environmental factors)?

We don’t quite know. Nothing has been isolated.

My basic argument is that it is intrinsic to the human survival mechanism that we have this capacity to repeatedly kill. Killers are anachronisms whose primal instincts are not being moderated by the more intellectual parts of our brain.

Perhaps it’s not that serial killers are made, but that the majority of us are unmade, by good parenting and socialization. What remains behind is these un-fully-socialized beings with this capacity to attack and kill. And often that capacity is grafted onto a sexual impulse – aggression sexualized at puberty.

Many serial killers are survivors of early childhood trauma of some kind – physical or sexual abuse, family dysfunction, emotionally distant or absent parents. Trauma is the single recurring theme in the biographies of most killers.

Are there any cases of serial killers who had well-adjusted childhoods?

Most serial killer biographies are self-reported, so you are relying on what they tell you. That being said, there do seem to be some examples. Ted Bundy is a classic one. No one has really found any evidence of “trauma” in his childhood, in the dramatic, traditional sense. He did, however, grow up believing that his mother was his sister.

We had a killer here in Canada who was the commander of an air force base. He was flying the equivalent of Air Force One – flying around the prime minister, visiting dignitaries – then suddenly in his 40s, a colonel, he commits two sexual homicides. He is a mystery. There is nothing in his childhood to explain his behavior. There is also the strangeness of the late age at which he started.

I am currently studying a serial killer called Richard Cottingham. I talked to him in prison last month. He comes from a nuclear family … the father was there, the mother was there, and there is no clear history of trauma or abuse. It could be that there is something but he doesn’t want to admit it. I really don’t know.

But there is nothing in his past that obviously parallels the early lives of, say, Charles Manson or Henry Lee Lucas. When you read these killers’ biographies it is no surprise they turned into what they did.

If killers are the products of childhood trauma, or underdeveloped brains, are they still “responsible” for their actions?

It’s true that almost all serial killers suffered childhood trauma. But here’s the problem: if 100 kids grow up in an abusive foster home, and one turns out to be a serial killer – what about the other 99? They grew up to be, well, maybe not all well-adjusted citizens, but certainly not serial killers. What is the missing X factor?

My sense is responsibility falls on the offender here. Serial killers choose to act on their compulsions.

During the first big wave of celebrity serial killers in the 1960s and 1970s, some defense lawyers tried to argue in court that serial killers are not guilty by reason of insanity, because an irresistible compulsion to kill is a form of temporary insanity. The legal definition of insanity is an inability to distinguish right from wrong and an inability to understand the consequences of an action. But serial killers are very aware of what they’re doing. That’s why they disguise themselves, hide evidence, leave the scene of the crime.

One can make the argument that serial killers suffer from psychopathy, that because they are psychopaths they have no sense of remorse or empathy and their decision-making process is faulty. Interestingly, however, not all serial killers are psychopaths, according to the Hare test, a psychiatric diagnostic – or at least don’t test as such.

What exactly is psychopathy?

The number one trait of a psychopath is a lack of empathy. Others are a tendency to lie, a need for thrills – psychopaths become bored very quickly – and narcissism. But the lack of empathy is the biggest thing.

One common explanation is that psychopaths experience some kind of trauma in early childhood – perhaps as early as their infant state – and as a consequence suppress their emotional response. They never learn the appropriate responses to trauma, and never develop other emotions, which is why they find it difficult to empathize with others.

They grow up not knowing how to “feel”, and learn instead how to manifest what they think are emotions or the correct appearances of emotion. They know the “mask” they should wear.

In the case of serial killers, that’s why there are individuals who can raise a family, be what most people would consider a good spouse and parent, and at the same time have secret second lives where they go out and kill strangers. They can compartmentalize.

What do you make of Bruce McArthur, the alleged Toronto gay village killer arrested earlier this year?

Bruce McArthur is interesting because he was apprehended at such a late age. He is way beyond the statistical norm for when serial killers first kill – so either he has been killing for decades, and we have not yet identified his earlier victims, or he is some kind of new breed of serial killer; an evolution in that phenomenon – someone who kills very late in their life when most serial killers have already begun “retiring” because their testosterone is declining.

If McArthur has been committing crimes since the 1970s or 1980s then this is going to be an extremely difficult investigation. Currently law enforcement are looking at his dating apps for evidence and to link him to more possible victims. But they didn’t have that kind of stuff then.

How common are same-sex serial killers?

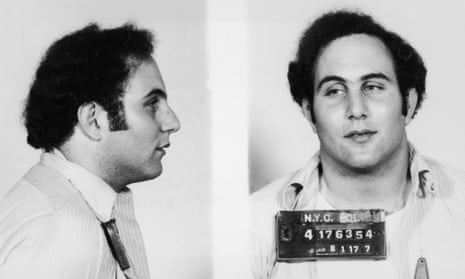

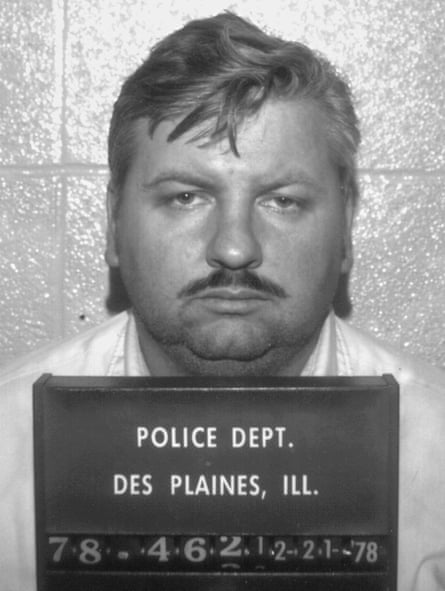

There have been dozens of gay serial killers. Probably the most notorious were John Wayne Gacy and Jeffrey Dahmer. So that alone is not unusual.

There is obviously a lot less stigma about being gay today than there was in the 1960s or 1970s or even 1980s. Then, gay serial killers were sometimes more effective because both they and their victims were living a secret double life. They were already kind of acclimatized to surreptitious behavior – covering up what they are.

Closeted people are still particularly susceptible to victimization by predators. If there are no witnesses or confidantes – family members and so on – able to link your disappearance to the killer, that gives the killer an advantage.

What about female serial killers?

Roughly one in every five to six serial killers are female. There are significant differences in their psychopathology from male killers.

Research on female serial killers is difficult because they are fewer and harder to catch. Female serial killers have less tendency to leave bodies behind. They are quiet killers; they have longer killing careers. They are much better at it.

There is a less sadistic tendency. They tend not to torture their victim and they are less interested in mutilation. But the motivation is similar – the need for control over their victim. It’s not sex, it’s control, though they may assert it through sexual acts.

Aileen Wuornos is the classic example – a female serial killer in Florida. She worked as a prostitute and would kill her clients. A couple of documentaries have been made about her, and a feature film (Monster, with Charlize Theron). Here was a serial killer motivated by pure rage.

The types of predation in which female serial killers engage are often an extension or perversion of gender roles. For example, the expectation that women are in nurturing roles, caring roles. You have a category of female serial killers with Munchausen syndrome by proxy – mothers killing children, nurses killing patients.

Is it true, as some have suggested, that serial killing is now on the decline? Or is it just less reported in the media?

You know, it appears that we’re arresting and apprehending less serial killers, and when we do apprehend them they have a much smaller victim list, per killer. So yes, there seems to be a decline in American serial killing. Either there are less serial killers or we have gotten better at catching them earlier.

We have had huge breakthroughs in forensic technology, especially DNA science. Many of the serial killers who were arrested in the 1990s and 2000s were arrested for crimes committed earlier.

Do you know of any examples of serial killers who have expressed remorse?

Sort of. They may reach an age where they think “I should be making amends”. They may not feel it, but they think that they “ought” to. I know of an example of a guy who in several decades had only given one interview. He was approached by the daughter of one of his victims, and he completely opened up to her.

It seems like the more research there is on serial killers, the more we realize how little we know.

We are floundering. We are floundering in masses of information but very little knowledge coming out of that information. We seem to know less about serial killers now than we thought we did 20 years ago. We are only now realizing how little we know. That’s partly because the more serial killer case studies we aggregate, the less clear the patterns become. We are starting to see all these anomalies.

As we as a society become more scientific and less philosophical it becomes more difficult for us to explain this kind of abnormal behavior. All that is left is the very human definition: evil. But what is that? It is not a term that can be tested or duplicated in the scientific sphere. It was easier when we just thought of them as monsters.

This transcript has been edited and condensed for clarity.