Here’s the thing: Aaron Sorkin is one of the greatest writers who’s ever lived. That’s not hyperbole. From TV to film to the stage, Sorkin has crafted some of the most eloquent, most charged, and most memorable lines spoken by a cadre of Hollywood’s greatest performers. He’s also prolific, but not to the point of anonymity. You know a Sorkin-written movie when you see one, and out of nine produced feature films he’s written, only one of them is less than “good.” That’s one hell of a batting average.

Sorkin’s latest movie is his second directorial effort, The Trial of the Chicago 7, and it’s available on Netflix starting today. It uses a story from our past (the 1968 Democratic National Convention protests) to talk about the world we live in now, and it does so with Sorkin’s signature crackling dialogue and soaring speeches, but also with some stunning nuance and genuinely cinematic filmmaking.

With Chicago 7 now available, I – as a massive fan of Sorkin’s work – felt it was a fine time to revisit every Sorkin movie made thus far, see how they hold up, and somewhat arbitrarily rank them from worst to best. This ranking is really just an excuse to dig into the diversity of Sorkin’s filmography, and doesn’t even touch upon his stellar work in the world of television. But it is a nice reminder that the guy has written more than one masterpiece and, oddly enough, still has films that feel underrated.

So without further ado, here’s every Aaron Sorkin movie ranked.

9. Malice

“You ask me if I have a God complex. Let me tell you something: I am God.”

Malice is an absolutely wild movie. If you told me that Sorkin and Scott Frank, the film’s other credited screenwriter, were passing this script back and forth but were forced to include a twist dreamt up by M. Night Shyamalan every 20 pages, I would 100% believe you. This is far and away the worst movie with Sorkin’s name on it (and his only bad one, for that matter), but it’s never uninteresting and it’s far from Sorkin’s fault – Harold Becker was the director. Malice is a melodrama with a serial killer subplot for some reason, with Bill Pullman and Nicole Kidman playing a happy couple whose lives are upended when a high school acquaintance of Pullman’s character who also happens to be a hotshot surgeon (played with devilish charm by Alec Baldwin) rents the room on their third floor.

Pullman, Kidman, and Baldwin are all quite good in the film, doing their darndest to sell every last ounce of soapy drama that comes across the screen. It’s just that the movie is confused about what, exactly, it is, what story it’s telling, who its characters are, and what it wants to say. Which is a little bit of a problem. There is one genuinely good scene though and it’s pure Sorkin: Baldwin’s character, under deposition, delivers a monologue in which he adamantly claims that he is God. And honestly? Malice is worth watching for that (and the insane twists and turns) alone.

8. Charlie Wilson's War

“My loyalty! For 24 years people have been trying to kill me. People who know how. Now do you think that’s because my dad was a Greek soda pop maker? Or do you think it’s because I’m an American spy? Go fuck yourself, you fucking child!”

Sorkin and director Mike Nichols make for a very fine match, and while Charlie Wilson’s War is a solid double, it doesn’t quite stick the landing. This is a film set during that 1980s that is ostensibly about how we got to 9/11, telling the true story of a U.S. Congressman named Charlie Wilson (a delightfully Southern Tom Hanks) who covertly diverted federal funds to arm the Afghan people against the invading Soviet Union. It’s fun and filghty and Hanks gets to mingle his “aw schucks” charm with a dash or two of rambunctiousness (Charlie’s a bit of a partier), but the story wraps up in a feel-good way that doesn’t quite jibe with the buildup of the film. Indeed, the original ending as conceived by Sorkin (and it was actually filmed) was a devastating punchline about how the U.S.’s refusal to educate or build infrastructure for the Afghans after arming them was a contributing factor to the events of 9/11. Nichols and even Hanks grew uncomfortable with the downer ending and changed it, against Sorkin’s protests.

For that reason Charlie Wilson’s War adds up to a “pretty good” movie that charms but doesn’t really linger, and one imagines if it had the guts to really follow through on that finale we’d have had something more to chew on. But as is, the script sheds a fascinating spotlight on how things do (and don’t) get done in congress, and Philip Seymour Hoffman gives an uproariously funny performance as the chief CIA operative helping Charlie with his covert operation. Indeed, it’s a testament to Sorkin’s talent that even a film that’s just OK like Charlie Wilson’s War still contains one of the writer’s best scenes – the do-si-do in Charlie’s office when he first meets Hoffman’s character. Pure gold.

7. Molly's Game

“Because it’s my name… and I’ll never have another.”

It’s kind of incredible that Sorkin’s first directorial effort wasn’t on one of his TV shows, but with a feature film starring an Oscar-nominated actress. And Molly’s Game is really good! Except for that one scene that just kind of sticks out like a sore thumb.

Adapting the story of Molly Bloom could have gone a number of ways, and Sorkin kind of manages to have his cake and eat it too – it’s a poker movie, a courtroom drama (without the courtroom), and a character drama all at once. And a female-led one at that! Much has been written by far better (and more qualified) writers than me about the treatment of female characters in Sorkin’s work, but suffice it to say the guy is a bit hit or miss. C.J. Cregg is great and brilliant and complex! Mackenzie McHale is, well, less so.

But Molly’s Game by and large is a compelling and wildly entertaining story about a complicated woman. Chastain gives a layered, commanding performance and she gets to rattle off some truly terrific Sorkin dialogue. He handles the poker scenes with ease, and proves more than capable of directing a large cast and handling multiple locations, all while piecing the story together in a way that’s entertaining and quick-paced.

And then comes the scene where Molly’s father explains to her what her root emotional trauma is. Yikes. I understand Sorkin’s intention here, but that particular scene just kind of knee-caps Molly’s Game as it’s coming in for a landing. Aside from that, it’s an assured, crackerjack directorial debut for which Sorkin admirably went outside his comfort zone – in more ways than one.

6. The Trial of the Chicago 7

“Tom says to tell Abbie that we’re going to Chicago to end the war, not to fuck around.”

For Sorkin’s second directorial effort, he returned to the courtroom drama genre where he first made a name for himself. But this time, he used true events of the past to speak directly to the world we live in today.

Aaron Sorkin wasn’t supposed to direct The Trial of the Chicago 7. He wrote the script back in 2007 for Steven Spielberg to direct, but the project got hindered by a number of factors, and languished in development hell. Then 2016 happened. Having seen Molly’s Game, Spielberg said Sorkin should direct Chicago 7 himself, and the result is an elegant, infuriating, ultimately rousing story about the power of protest.

The Trial of the Chicago 7 takes place before, during, and after the events of the 1968 Democratic National Convention, where violence erupted between police and protestors who had gathered to voice their anger over the Vietnam War. Seven men were rounded up and put on trial for conspiracy, with an eighth man – African-American activist Bobby Seale, who had nothing to do with the protests – roped into their case in an attempt to negatively affect their optics. The resulting trial was a sham, with the judge making his hatred and displeasure for these counter-culture activists abundantly clear.

And Chicago 7 is kind of great. All of the men on trial were opposed to the Vietnam War, the establishment, and/or the government in some way, shape or form but they differed on how best to enact positive change. At its heart, the film is about not only the different kinds of protest that exist and their merits, but the power of said protest, and how speaking truth to power is important even in the face of a system that’s working against the people it’s supposed to protect. Like a lot of Sorkin’s work, it flirts with melodrama but doesn’t ever really cross that line. The performances from Mark Rylance, Eddie Redmayne, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, Sacha Baron Cohen, and Frank Langella see to it that the soaring dialogue is delivered with measured aplomb, which makes the film’s message all the more powerful.

Visually, too, Chicago 7 is a step up from Molly’s Game, as Sorkin is more confident behind the camera this time around as he brings a calm elegance to the court proceedings and a brutal reality to the protest sequences. Chicago 7 solidifies Sorkin as a filmmaker in his own right, which isn’t too shabby for one of the best writers working today.

5. The American President

“Let me see if I got this. The third story on the news tonight was that someone I didn’t know 13 years ago, when I wasn’t president, participated in a demonstration where no laws were being broken, in protest of something that so many people were against it doesn’t exist anymore. Just out of curiosity, what was the fourth story?”

Sorkin’s early work veered a bit more towards the romantic, as was the prominent tone for most studio dramas at the time, and it has suited his sensibilities well. Obviously his most romantic film is The American President, the 1995 feature that reunited him with director Rob Reiner as served as a precursor to his NBC series The West Wing, one of the greatest TV shows of all time. The American President is a romantic comedy first and a political drama second, and that makes all the difference in the world. The film’s chronicle of the political innerworkings of the White House and congress are slightly elevated and a little unbelievable, but none of that really matters because what you really care about is the relationship between President Andrew Shepherd (Michael Douglas) and lobbyist Sydney Ellen Wade (Annette Bening).

The dialogue in The American President is beautifully symphonic at times, especially as it relates to President Shepherd’s speeches, and Sorkin’s knack for back-and-forths between characters clearly fits well within the romcom genre. You genuinely fall for and care about Andrew and Sydney’s relationship, which is no small feat, and Douglas and Bening have terrific chemistry together. It also helps that the ensemble is filled out by wonderfully likable performers giving wonderfully likable performances, from Martin Sheen to Michael J. Fox to Anna Deavere Smith. This sweet and genuinely romantic movie also gave us The West Wing, and for that we should be forever grateful.

4. A Few Good Men

“I strenuously object? Is that how it works? Hm? ‘Objection.’ ‘Overruled.’ ‘Oh, no, no, no. No, I strenuously object.’ ‘Oh, well if you strenuously object then I should take some time to reconsider.’”

Sorkin really nailed it out of the gate, didn’t he? A Few Good Men started as a play, but hadn’t even opened yet before he sold the film rights. It’s a tremendously well-written piece, and while director Rob Reiner does his best to make it cinematic, what you remember most about A Few Good Men is the lines and the performances, not necessarily the visual flourishes. Who needs pyrotechnics when you have Jack Nicholson giving one of his best performances?

The film is essentially the story of trying to do good in a world that doesn’t really reward that kind of thing. Speaking truth to power is a theme prevalent through much of Sorkin’s work, and it’s front and center in A Few Good Men as Lieutenant Daniel Kaffee (Tom Cruise) tries to do the right thing for once in his life when he’s handed a court-martial case in which two Marines are charged with murdering a fellow soldier.

This is the kind of movie that grabs you from the first scene and doesn’t let up, building to the explosive standoff between Cruise and Nicholson on the witness stand. It’s a masterclass in building rhythm and tension using dialogue, but it takes the right actors to really make Sorkin dialogue soar and the casting of this one was absolutely perfect. Sorkin may have evolved and tackled different themes over the years, but A Few Good Men remains one of the best movies he’s ever made over two decades later.

3. Moneyball

“I know these guys. I know the way they think, and they will erase us. And everything we’ve done here, none of it’ll matter. Any other team wins the World Series, good for them. They’re drinking champagne, they get a ring. But if we win, on our budget, with this team… we’ll have changed the game. And that’s what I want. I want it to mean something.”

Moneyball is unique in Sorkin’s filmography in that it’s one of only two films on which he shares screenplay credit. Now you may be wondering, I didn’t think Aaron Sorkin co-wrote screenplays? And you’re right! On the aforementioned Malice, Scott Frank took a crack at the screenplay when Sorkin was called away to finish up A Few Good Men. That result was less than stellar. But in the case of Moneyball, Sorkin was brought in to perform rewrites on an existing script by Steven Zaillian (Schindler’s List), and not to put too fine a point on it but they knocked it out of the park. Sorkin and Zaillian separately worked on the screenplay as director Bennett Miller set about getting the film ready to shoot (he took over for Steven Soderbergh, who was abruptly dropped from the project over creative differences), and the result is kind of a perfect mind meld. It’s not quite a Sorkin movie and not quite a Zaillian movie, but you can feel each writer’s DNA all over the piece.

And as a film? Moneyball absolutely rules. It’s a sports movie that’s about the effect of sports on human beings, not how well the humans play the sports. In that way it feels unique and fresh, as Miller really relishes quiet scenes between the managers, scouts, and players that reveal something about the men at the story’s center.

And in that center is Brad Pitt’s Billy Beane, a former player who washed out and eventually became general manager of the Oakland Athletics. He enlists a Yale economics graduate (Jonah Hill) to embrace sabermetrics, using statistics to make decisions regarding which players to obtain and play. It’s a controversial practice that puts everything on the line and causes friction with the team’s manager (Philip Seymour Hoffman, absolutely killing a relatively small role). But again, the film is less concerned with the nuts and bolts of who wins and who doesn’t than it is with how these actions and interactions affect the human characters.

Billy Beane can’t stand to watch the games. What at first feels like superstition soon reveals a complete lack of self-confidence – Billy doesn’t steer clear from the games because he’s afraid he’ll jinx it, he does so because he doesn’t feel like he deserves to be there. Moneyball is a film about regret and penance and trying to prove to oneself that they’re worthy. Worthy of their job, of their role as a father, of their reputation. Pitt is absolutely heartbreaking here, delivering one of the best performances of his career that also feels like a direct comment on his transition from Hollywood hunk to serious actor. It’s also a devastating father/daughter story. The final shot of the film, close on Pitt’s eyes as he listens to his daugther’s song, is a complete and total gut-punch.

There are scenes that feel like classic Sorkin, but they work organically with the piece as a whole, and his and Zaillian’s work compliments one another really well. Moneyball is a movie that kind of shouldn’t work, but all the pieces coalesce – the writing, Miller’s precise and patient direct, the evocative score, Wally Pfister’s intimate cinematography – into one of the best films of the 21st century.

2. Steve Jobs

“It’s not binary. You can be decent and gifted at the same time.”

Speaking of films that shouldn’t work, Sorkin took on the unenviable task of writing a Steve Jobs biopic and ended up crafting one of the best and most original biographical films ever made. Steve Jobs is, quite simply, an underrated masterpiece. Instead of trying to tackle the life of the Apple visionary from cradle to grave, Sorkin’s script is divided into three very distinct acts, each of which takes place just before a new product launch and plays out in roughly real time. This structure in and of itself would be fascinating and unique, but that Sorkin is able to pack it to the brim with so much character and information and a genuine arc without anything feeling inorganic is downright miraculous.

Steve Jobs was a difficult man. Some would go so far as to say he was a bad man. Steve Jobs doesn’t attempt to cast aspersions or judgment, but to instead investigate what made this person – who undoubtedly changed the way we live our lives more than once – the way he was. The throughline, of course, is Jobs’ relationship with his daughter Lisa, who he befuddlingly refused to acknowledge as his child for years despite DNA evidence to the contrary. Who does that? And how can someone live with that?

An argument could be made that Steve Jobs is Sorkin’s best script, given the sheer level of difficulty and how entertaining and dynamic and complete the whole thing feels. And while I still wonder what David Fincher’s version of this would have looked like, director Danny Boyle adds some innovative touches that go a long way towards making this cinematic – including shooting in 16mm, 35mm, and digital for the three acts, respectively. I adore this movie.

1. The Social Network

“You are probably going to be a very successful computer person. But you’re going to go through life thinking that girls don’t like you because you’re a nerd. And I want you to know, from the bottom of my heart, that that won’t be true. It’ll be because you’re an asshole.”

Remember when The Social Network came out and there was a whole discussion around whether the film was too harsh on Mark Zuckerberg? Ah, simpler times. But even given the fact that, in hindsight, The Social Network went a little too soft on ol’ Zuck, it still remains a stone-cold masterpiece, Sorkin’s best movie, and one of the defining films about the 21st century.

When it was first announced that Aaron Sorkin was writing “a Facebook movie” people laughed. When Fincher signed on they were confused. When they saw the first trailer they were intrigued. And when they saw the film they were blown away. From the opening scene – quite possibly the best scene in Sorkin’s career thus far – to the film’s devastating punchline there’s not a single false move. It’s engrossing, entertaining, disturbing, hilarious, and absolutely crushing, and that Fincher is able to keep all these plates spinning in the air without them crashing down is a testament to his meticulousness and acuity as a filmmaker.

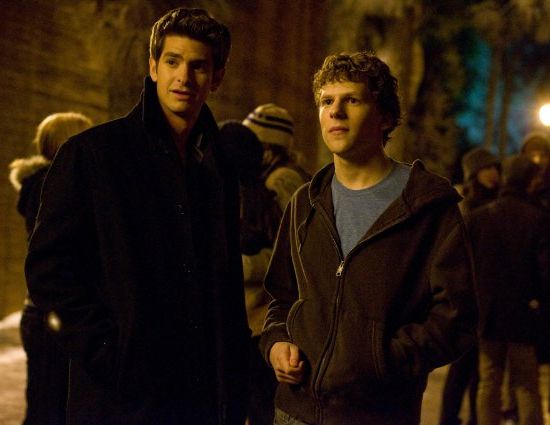

Indeed, I can’t think of a better example of a marriage between a writer and director than Sorkin and Fincher on The Social Network. They elevate each other’s best tendencies while dampening each other’s worst, telling a genuinely Machiavellian story about how a kid changed the world from his dorm room. Jesse Eisenberg is at once pathetic and sinister; Andrew Garfield is charmingly naïve; Justin Timberlake exudes unearned confidence; and Armie Hammer activates every insecurity in Zuckerberg’s bones each time they share the screen. Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ Oscar-winning score is icy and chilling, evoking the drama onscreen, and Fincher and cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth unsurprisingly bring the whole thing together in deliciously sharp, dark visuals. Again, not a single false move.

But The Social Network endures not just because it dared expose Mark Zuckerberg as kind of a jerk, or because it’s full of quote-worthy lines (“I’m 6 foot 5, 220, and there’s two of me” never gets old), or even because it so brilliantly encapsulates a 21st century society run by twentysomething wunderkind tech geniuses completely devoid of emotional maturity or empathy. It endures because it’s a great fucking movie, and because themes like failing to connect with a significant other or losing your best friend are extremely relatable and tragic. The greatest trick The Social Network pulled was getting us to empathize with Mark Zuckerberg, even just a little. That’s no small feat.

Adam Chitwood is the Managing Editor for Collider. You can follow him on Twitter @adamchitwood.