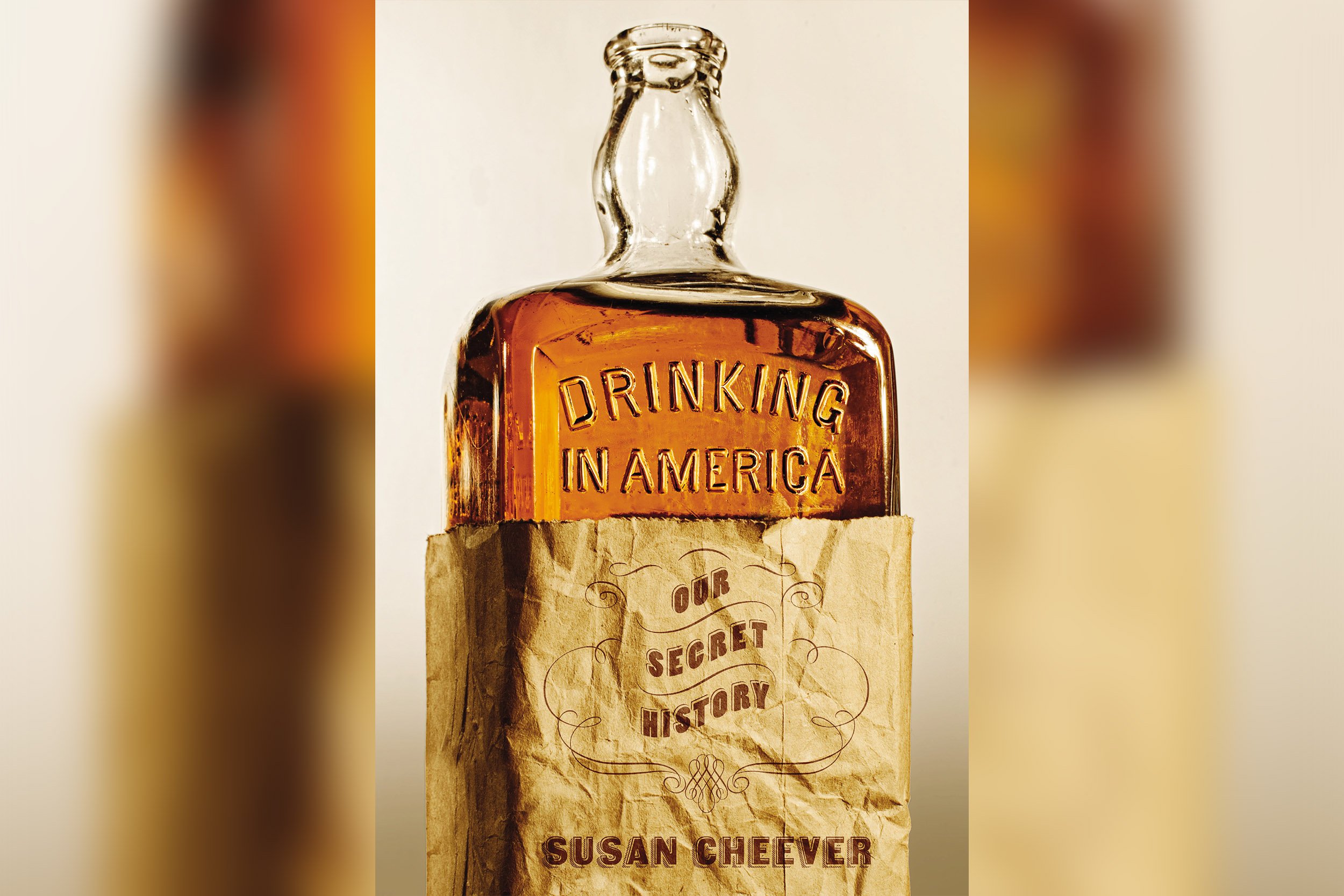

From the book Drinking in America: Our Secret History. Copyright (c) 2015 by Susan Cheever. Reprinted by permission of Twelve/Hachette Book Group, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

At 12:30 p.m. on November 22, 1963, bullets fired into the open roof of the presidential limousine tore through John F. Kennedy's body.

The first shot went through the president's neck but did not kill him. A second, fatal shot ripped through his brain and his skull almost four seconds later.

During the critical time between the two shots, seconds in which the president's life might have been saved, the Secret Service agents within a few feet of the man they were duty bound to protect failed to take the evasive actions they had been trained to do.

Roy Kellerman, the leader of the security detail, riding in the passenger seat of the limousine, wasn't sure what was happening. He turned to see the president grasping his neck.

William Greer, at the wheel of the presidential limo, did not at first speed up or swerve away from the noise. Neither Paul Landis, on the running boards of the vehicle trailing Kennedy's, nor Jack Ready in front of him jumped forward to protect the president.

Lyndon Johnson, riding two cars back, was startled by the sound of the first shot. "Others in the motorcade thought it was a backfire from one of the police motorcycles, or a firecracker someone in the crowd had set off," writes Robert Caro in his biography of Lyndon Johnson, The Passage of Power.

Even the official commissions disagree about what happened that day. Were there three shots or four? Did all the bullets come from the window of the Texas School Book Depository—where assassin Lee Harvey Oswald stood with his 6.5-millimeter Carcano Italian infantry carbine?

Did the first bullet pass through President Kennedy and continue on to wound Texas governor John Connally, who was sitting in the forward jump seat of the limousine with his wife, Nellie? Whose decision was it to forego using the main limo's plastic bubble, built to shield those in the passenger seats?

Why were there no Secret Service agents on the running boards of the president's car?

Those fatal seconds, although they were caught on film by several amateur cameramen, still elude our understanding. But one thing about those moments—one thing on which all the commissions agree—has gone relatively under-reported during the five decades since.

Nine of the twenty-eight Secret Service men who were in Dallas with the president the day he died had been out in local clubs until the early hours of the morning—in one case until five a.m. Three of the Secret Service agents riding a few feet from the president in the follow-up car had been, by their own accounts, up very late and drinking, an activity prohibited in the Secret Service rulebook.

A week after the events in Dallas, President Lyndon Johnson ordered the first official investigation of the assassination. Its chairman: Earl Warren, the chief justice of the Supreme Court, who had had a distinguished career as the governor of California.

The Warren Court, during his fourteen years as chief justice, had heard many pivotal cases, including Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, with its landmark civil rights decision. With an already established reputation and an eye on the political thicket that would surround an investigation into Kennedy's assassination, Warren hesitated to accept Johnson's mandate. Johnson prevailed.

Three days after reluctantly taking the job, Warren learned that Secret Service agents had been out on the town socializing and drinking until early morning the day of the assassination.

The revelation came not from depositions but from a radio report followed up by a December 2 newspaper column in The Washington Post by Drew Pearson, the establishment journalist (and close friend of Chief Justice Warren) well known for speaking truth to power.

Pearson wrote that the Secret Service agents had visited the Fort Worth Press Club after midnight and that six of them had proceeded to an offbeat place called the Cellar Coffee House. Some of the agents were out until nearly three a.m. and "one of them was reported to have been inebriated," Pearson wrote.

Pearson explained that his information had come to him through Thayer Waldo, a Fort Worth Star-Telegram reporter who didn't think his editors would dare publish a story casting aspersions against Secret Servicemen or the Fort Worth club owners, employees and patrons.

"Obviously men who have been drinking until nearly three a.m. are in no condition to be trigger-alert or in the best physical shape to protect anyone," Pearson wrote about the Secret Service agents in the Kennedy motorcade.

The Warren Commission duly questioned the Secret Service agents in question about their activities the night before the assassination and found they had been drinking. But in the 1960s the pastime of drinking with peers or colleagues was considered normal, acceptable behavior in many circles. Because of the lack of social stigma associated with drinking, it was hard for the panel's members to know how to react.

Philadelphia assistant district attorney Arlen Specter, who had reluctantly taken the Warren Commission job, and who debriefed the agents for the Warren Commission, didn't consider their behavior a severe problem. Indeed, the agents themselves were already devastated by their failure to protect the president, who most of them had revered.

Although the agents had broken the rules, many involved with the commission were eager to protect them from going down in history as the men who had made the mistakes that may have doomed the president.

Chief Justice Warren, however, was outraged. His ire finally found a voice in June 1964, when the commission questioned James Rowley, the director of the Secret Service. Under oath, Rowley admitted that Drew Pearson's column had been more or less accurate. Some had been drinking scotch; others, "two or three" beers.

After forcing Rowley to read the agency's regulations that "the use of intoxicating liquor of any kind...is prohibited," General Counsel J. Lee Rankin hammered him. Even though drinking was a firing offense, according to the manual, Rowley had fired no one. "How can you tell," Rankin asked, that the men's actions "the night before...had nothing to do with the assassination?"

Rowley bobbed and weaved. He had thought about punishment, he admitted. On the other hand, he had not wanted to blame the agents for the assassination—he did not want to "stigmatize" them or their families.

These answers seemed to infuriate Warren. "Don't you think that if a man went to bed reasonably early, and hadn't been drinking the night before, he would be more alert than if he stayed up until three, four, or five o'clock in the morning, going to beatnik joints and doing some drinking along the way?"

Warren noted that some citizens along the route of the motorcade, waiting for the president to pass by, had actually seen a gun barrel pointed out of the sixth-floor window of the Texas School Book Depository. None of the Secret Service agents had noticed it.

"Some people saw a rifle up in that building," Warren went on. "Wouldn't a Secret Service man in this motorcade, who is supposed to observe such things, be more likely to observe something of that kind if he was free from any of the results of liquor or lack of sleep than he would otherwise? Don't you think that they would have been more alert, sharper?"

Long work shifts and a tolerance for partying and drinking had become entrenched in the Secret Service during JFK's years in office, and this extended to the men in charge of the president's security.

Although there have been a handful of Secret Service drinking scandals since then, the early 1960s seem to have been a particularly difficult time for Secret Service agents.

"Agents acknowledged that the Secret Service's socializing intensified each year of the Kennedy administration, to a point where, by late 1963, a few members of the presidential detail were regularly remaining in bars until the early morning hours," investigative journalist Seymour M. Hersh would note in his book The Dark Side of Camelot.

Hersh reported that things were so loose that at least three of the Kennedy women—sisters and cousins from the president's large family—had propositioned various agents. All of this rule-breaking behavior among members of the extended Kennedy family should have made the Secret Service more alert and more responsible. Instead, it seemed to have the opposite effect.

Whether or not they were hungover on November 22, several agents were certainly sleep deprived, a not-uncommon state among Secret Servicemen at the time.

Agent Gerald Blaine, also in the Dallas motorcade, remembered struggling to stay awake on numerous occasions and spoke of being afraid to sit down or lean against a wall lest he nod off: "Working double shifts had become so common since Kennedy became president that it was now almost routine. The three eight-hour shift rotation operated normally when the president was in the White House, but when he was traveling...there simply weren't enough bodies."

Not only did many agents lack sleep, they rarely had time to eat. In his flight bag, along with extra ammunition and shoe polish, Blaine typically kept a few bags of Planters peanuts—sometimes the only thing he ate all day.

The Secret Service, one of the oldest federal law enforcement agencies, was founded in the nineteenth century to investigate financial crimes and curb counterfeiting after the Civil War. The department's formation was one of the last things President Abraham Lincoln approved in a conversation with Secretary of the Treasury Hugh McCulloch the day of his assassination.

(Lincoln's bodyguard, John Parker, was taking a break at a bar across the street when John Wilkes Booth approached the presidential box and fired a single, mortal shot.)

Then, in 1881, President James Garfield, waiting at the Washington, D.C., railroad station for a train meant to take him on a visit to New England—and unaccompanied by any kind of bodyguard—was assassinated by a man who thought God was telling him to kill the president.

It wasn't until the administration of Grover Cleveland, when a stranger walked into the White House and hit the president across the face, that the Secret Service became part of a unit intended to guard the nation's chief executive.

The first twenty-five U.S. presidents had bodyguards but no official security detail, and the idea of protecting a leader from his own people was, at first, an unpopular one. Yet the need for close security became a governmental necessity in 1901, when an anarchist in Buffalo, New York, approached President James McKinley, who was loosely flanked by three Secret Service agents, and fatally shot him from only a few feet away.

By the 1960s the Secret Service had evolved into an elite corps of physically impressive men, adept in the use of firearms and ready to meet all emergencies, even at the cost of their own lives. Despite the agency's stature, two problems have always undermined it. One has been the desire of presidents to be physically accessible to the American public, but the other is more serious, especially when things go wrong.

From the beginning, the macho pride of the armed men of the service has made it a culture that has masked its weaknesses. Pride is not flexible and it does not ask for help. And since tough guys don't complain, problems have often been downplayed.

Sleep and careful eating were for sissies. Training was for beginners. In certain cases in the 1960s, physical fitness requirements were just a matter of filling out forms. Being a man who could hold his liquor was part of the MO. Indeed, First Lady Betty Ford liked to joke that when she got sober, some members of her Secret Service contingent who had to accompany her to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings ended up getting sober as well.

Even in recent years, this machismo mindset has bedeviled the agency. Though the agency has gone through repeated reforms, the past decade has seen nearly nine hundred incidents in which officials were charged with misconduct. In the past three years alone, three reprimands for misbehavior turned into public scandals.

In 2012, agents doing advance work for an official visit to Colombia by President Obama cavorted with strippers in their hotel; thirteen were investigated, and four were demoted or fired.

In 2013, a Secret Service supervisor in the president's detail picked up a woman at the bar of the Hay-Adams hotel in Washington, D.C., then went upstairs with her to a hotel room, leaving behind a bullet from his Sig Sauer semiautomatic pistol when he left.

And in March 2014, in Holland, after a Secret Service squad went out well into the night and one Counter Assault Team member was found drunk and passed out in a hotel hallway, three agents were shipped back stateside and put on leave.

President John F. Kennedy, beginning his campaign for a second term, traveled more than any previous president. Traveling had always been a nightmare for the Secret Service, especially when it involved the First Lady and other eminent guests and their families.

"Motorcades were the Secret Service's nemeses," agent Gerald Blaine would write. "There were an endless number of variables...and you could never predict how a crowd would react." In Dallas, against department regulations, the president and the vice president—Lyndon Johnson—would ride in the same motorcade, making the situation even more unstable in the eyes of the men there to keep them from harm.

Kennedy wanted to be physically close to his constituents. And for all his personal courtesy to his guardians, including his motorcycle escorts, he made it clear that he was impatient with those who wanted to hem him in with security, especially the chosen few whose assignment brought them near enough to touch him.

At the start of his administration, four agents would typically ride along on the side of the president's vehicle, balanced on running boards affixed to the car. Their positions, however, often blocked well-wishers from approaching the president for a handshake or from having a direct line of sight to him.

At one point a few days before his death, Kennedy commanded his Secret Servicemen—whom he affectionately called a bunch of "Ivy League charlatans"—to stay off the exterior footrests because he felt they boxed him in.

It was the prospect of a good meal that led the Secret Service agents out of the Hotel Texas in Fort Worth the night of November 21. The president and the First Lady had retired to their suite, and the men had had no dinner; some of them hadn't eaten since breakfast in Washington, D.C.

Word got out that there was a buffet with food a few blocks from the hotel. In fact, local journalists had kept the Fort Worth Press Club open so that visiting White House reporters could go and grab a bite.

It was after one in the morning when nine of the twenty-eight agents in the presidential detail walked over in search of food. There was none. Though the kitchen at the club was closing, the agents stayed around for scotch and sodas, and a few cans of beer. Three of the agents then headed back to their rooms; six continued with the festivities.

CBS newsman Bob Schieffer—then a young night police reporter for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram—remembers the evening well.

"I went to the club when I got off at two a.m.," he recalls. Nearby was a legendary hangout called the Cellar Coffee House. "The Cellar was an all-night San Francisco-style coffee house down the street and some of the visiting reporters had heard about it and wanted to see it. So we all went over there and some of the agents came along. The place didn't have a liquor license, but they did serve liquor to friends—usually grain alcohol." (Fort Worth was a dry city in 1963, so the Cellar officially offered only fruit juice.)

Six Secret Service members stayed at the Cellar until close to three in the morning; one didn't leave until five a.m. "Every one of the agents involved had been assigned protective duties that began no later than 8:00 a.m. on November 22, 1963," observed Philip Melanson, an expert on incidents of politically motivated violence who would oversee the archive of the Robert F. Kennedy assassination.

On November 22, a morning mist had burned off, and bright sunshine greeted the presidential party, who had flown from Fort Worth to Dallas. Instead of getting in the limousine, President Kennedy and the First Lady walked along the chain-link fence separating the airfield from the public, shaking hands and chatting with the spectators.

Secret Service agents Clint Hill and Paul Landis scanned the crowd for trouble. Neither had had more than a few hours of sleep; both had been drinking into the early hours of the morning.

That morning, nine agents were specifically responsible for guarding the president. In the lead car—at the front of the motorcade, directly in front of Kennedy's limousine—sat agent Winston Lawson, along with Dallas police chief Jesse Curry. Behind them in the presidential limousine—the second car of the motorcade—the driver and passenger seat were occupied by Secret Service members William Greer and Roy Kellerman.

The limousine, a 1961 midnight-blue four-door Lincoln (code-named the SS-100-X), had been modified by the Ford Motor Company for presidential use. Four retractable side steps and two steps with handles on the rear of the car had been added to allow security personnel to jump on or off, or be escorted along. The side steps had been retracted.

Modifications had widened the car's wheelbase and increased its weight from 5,200 pounds to almost 7,800 pounds. Even for an experienced driver like Greer, who had been a chauffeur in Boston, it was a difficult vehicle to maneuver, especially on a route like the one in Dallas, which included some sharp right-angle turns.

Riding along that day were the Kennedys (code-named Lancer and Lace) and the Connallys. The third car, also configured with protruding footrests, was a 1956 black Cadillac convertible (code-named Halfback), driven by Secret Service agent Sam Kinney. It was Kinney's job to stay a few feet behind the presidential limousine at all times: close enough so that the two cars couldn't be separated by someone lunging between them, but not so close as to cause a collision.

Paul Landis, Jack Ready, and Clint Hill rode the running boards along the sides of this follow-up car. Inside sat agents George Hickey, Emory Roberts, Glenn Bennett and senior aide Ken O'Donnell.

Agent Hill—poised just a few feet behind the Kennedys, who sat in the backseat of the car in front of him—was nervous. The motorcade kept speeding up and slowing down, speeding up and slowing down. That morning, he frequently jumped off the running board to jog alongside the vehicle. Kinney, right behind him in Halfback's driver's seat, watched him struggle to keep pace with the cars.

Clint Hill had been assigned to the First Lady's detail; his job was to focus on her, not on the president. According to Hill, in Mrs. Kennedy and Me, one of two books he has written about the Kennedys, he and Mrs. Kennedy had developed a solid friendship.

They had first become good friends, he noted, after a propitious encounter. One day when he was in the passenger seat next to the driver while she was being chauffeured to Middleburg, Virginia, where she had rented a small estate for riding horses, Hill lit up a cigarette. She leaned forward and asked Hill to ask the driver to pull over.

Hill was baffled when she invited him to ride with her in the back seat. Perhaps she didn't like his smoking? Instead, with an impish look on her face, she asked Hill if she could have one of his cigarettes. Hill reached for his pack of L&M's and lit one for the First Lady. "She was like a giddy teenager who was getting away with something, and I was her cohort in crime," Hill writes.

Hill's laser focus on the First Lady may have also stemmed from a deeper affection for her, evident in the tenderness with which he would later write about her. After the first and second shots rang out, it was Hill who acted, climbing onto the rear of the Kennedys' limousine and pushing the First Lady—who had crawled onto the back of the car—back into her seat. It was already too late to save the president.

Across from Hill on the other side of the follow-up car, agent Jack Ready was also on the footboards, feet from the president. Behind him, in similar proximity, was Paul Landis, also from Mrs. Kennedy's detail.

Both men seemed paralyzed for a few moments. All three—along with Glenn Bennett, who was inside their chase car—had gone to the press club and then the Cellar the night before. Hill, Ready, and Bennett had stayed until after two a.m.; Landis, until five.

The fourth car in the motorcade, containing Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson and his wife, was guarded by other agents, including Rufus Youngblood. Youngblood had not joined the others the previous evening. And at the sound of the first shot, the agent, in line with his Secret Service training, pushed Johnson to the floor of the car and covered him with his own body, a move that none of the other agents would make in those precious few seconds to protect the president, the governor, or their wives.

The situation in Dallas, surely, had been exacerbated by President Kennedy's fearlessness—even recklessness—a charge later levied by some in his protective detail. It was the president who wanted to ride in an open car without the protective bubble. It was the president who insisted on going to Dallas, a staunchly conservative stronghold, even though a fellow Democrat, Adlai Stevenson, had recently been attacked there.

"Dallas is a very dangerous place," Kennedy had been told by his friend Arkansas Democrat senator J. William Fulbright, according to journalist Ronald Kessler in his book In the President's Secret Service. "I wouldn't go there. Don't you go." (Ironically, that first shot was fired at Kennedy at the very moment Nellie Connally had turned to the president to comment about the friendly Dallas crowds.)

Agent William Greer, who had served in the Navy during World War II, was clearly undone by the events of the day, although he had not been out with the other agents the night before. "Greer was tormented by his actions in the motorcade, including his failure to hit the accelerator immediately after hearing the first shot," journalist Philip Shenon writes. Witnesses remember seeing the car's brake lights illuminate at around the time the bullets were fired.

Later, Greer said he had been waiting for instructions from Roy Kellerman, the Secret Service agent in the passenger seat of the limousine. (Kennedy's two main escorts, Greer and Kellerman, were fifty-four and forty-eight at the time, respectively. In a department which prized speed and reflex—and in which forty was considered the age limit—the plum spots were often awarded to senior staffers.)

It would later become clear, however, that Greer, from the first, worried about his culpability. At Dallas's Parkland Hospital, where the president's body was rushed, Greer tearfully apologized to Jacqueline Kennedy, according to William Manchester, who interviewed the agent for his book The Death of a President.

Greer, who died in 1985, admitted he had told the First Lady: "Oh, Mrs. Kennedy, oh my God, oh my God. I didn't mean to do it. I didn't hear, I should have swerved the car, I couldn't help it. Oh, Mrs. Kennedy...if only I'd seen in time. Oh!"

His sense of guilt was echoed by Clint Hill, who in a TV interview with newsman Mike Wallace would break down in tears. "It was my fault," he admitted. "If I had just reacted a little bit quicker...I'll live with that to my grave."

The famous and horrific film sequence of the assassination—twenty-six seconds of eight-millimeter footage taken by a bystander named Abraham Zapruder—shows that the rest of the Secret Service agents, those in the presidential limousine and those riding behind in Halfback, seemed to be taken by surprise.

"The men in Halfback were bewildered," according to Manchester. "They glanced around uncertainly. Lawson, Kellerman, Greer, Ready and Hill all thought that a firecracker had been exploded.... Even more tragic was the perplexity of Roy Kellerman, the ranking agent in Dallas, and Bill Greer, who was under Kellerman's supervision. Kellerman and Greer were in a position to take swift evasive action, and for five terrible seconds they were immobilized."

Kellerman, who was riding in the passenger seat of the presidential limousine, also behaved oddly after the first shot rang out. Instead of moving back to protect his passengers, he stayed in the front, relaying radio messages to Greer, who was sitting a foot away, on his left.

The commission's Arlen Specter was not impressed. Kellerman, Specter said, "was the wrong man for the job—he was 48 years old, big and his reflexes were not quick."

The response of the Secret Service to Drew Pearson's allegations was fast and thorough. In an appendix to the Warren Commission report, Inspector Gerard McCann in Washington, D.C., and Secret Service agent Forest V. Sorrels, the special agent in charge of the Dallas office, canvassed everyone they could find who was at the Hotel Texas, the Fort Worth Press Club, or the Cellar Coffee House that night, including its manager, Jimmy Hill, and owner Pat Kirkwood, and a reporter who had also been at the party with the Secret Service agents.

Their conclusions? Letter after letter states that no one at Fort Worth that night was intoxicated. Letter after letter repeats that of the nine Secret Service agents at the press club and the Cellar, only three were due to report for the eight a.m. shift.

A dozen times in the report, respondents state that the Cellar was a dry club that served no alcohol. However, Philip Melanson writes, "At many clubs and restaurants in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, it was customary, given local liquor laws, for patrons to bring their own liquor, with the management providing setups."

Every agent on duty in Fort Worth and in Dallas was asked to write an account of his whereabouts and activities in the early morning hours of November 22. The agents say they went to the press club because they were hungry; none confesses to more than a drink or two. At the Cellar, the agents say, they drank fruit juice—mostly grapefruit juice. Two of them mention drinking a juice concoction called a "Salty Dick."

It took Pat Kirkwood, the Cellar Coffee House owner, more than twenty years to tell more details of what happened the night of November 21.

In the letters he wrote in 1963, he claimed that none of the Secret Service agents in his establishment had been drinking. But in 1984 he wasn't so sure. Kirkwood was fatally ill at the time, and the truth may have come to seem more important than it had before.

In an article recalling the glory days of the club, he explained that although he did not "officially" serve liquor, he actually dispensed large quantities of booze, especially to people like lawyers and politicians and policemen who might later be helpful.

Cellar manager Jimmy Hill would later own up as to the truth of what happened as well. After the assassination, he recalled in Jim Marrs's book Crossfire: "After the agents were there, we got a call from the White House asking us not to say anything about them drinking because their image had suffered enough as it was. We didn't say anything, but...they were drinking pure Everclear." (Everclear is 190 proof, a popular spike for a drink like the Salty Dick.)

How could the president's protectors have been so careless? What possessed the men guarding John F. Kennedy's life to think it was not unreasonable to drink and stay out most of the night before taking up their positions in a noontime motorcade?

Life can only be understood backward, but it must be lived forward, as Kierkegaard wrote. Of course none of the Secret Service agents knew on the warm night of November 21 in Fort Worth, Texas, that their movements were going to be scrutinized for decades.

None of them could have imagined that every move they made on that innocent Thursday night would be something they were called to account for minute by minute and second by second for the rest of their lives.

From the book Drinking in America: Our Secret History. Copyright (c) 2015 by Susan Cheever. Reprinted by permission of Twelve/Hachette Book Group, New York, NY. All rights reserved.

Susan Cheever's numerous other books include E.E. Cummings. A Life, My Name Is Bill: Bill Wilson—His Life and the Creation of Alcoholics Anonymous, Louisa May Alcott A Personal Biography, American Bloomsbury: Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Henry David Thoreau, Desire: Where Sex Meets Addiction, memoirs As Good As I Could Be, Home Before Dark, Note Found in a Bottle and Treetops, as well as novels Elizabeth Cole, Doctors and Women, The Cage, A Handsome Man and Looking for Work.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.