Expect the expected: Why China’s upcoming Party Congress promises few surprises

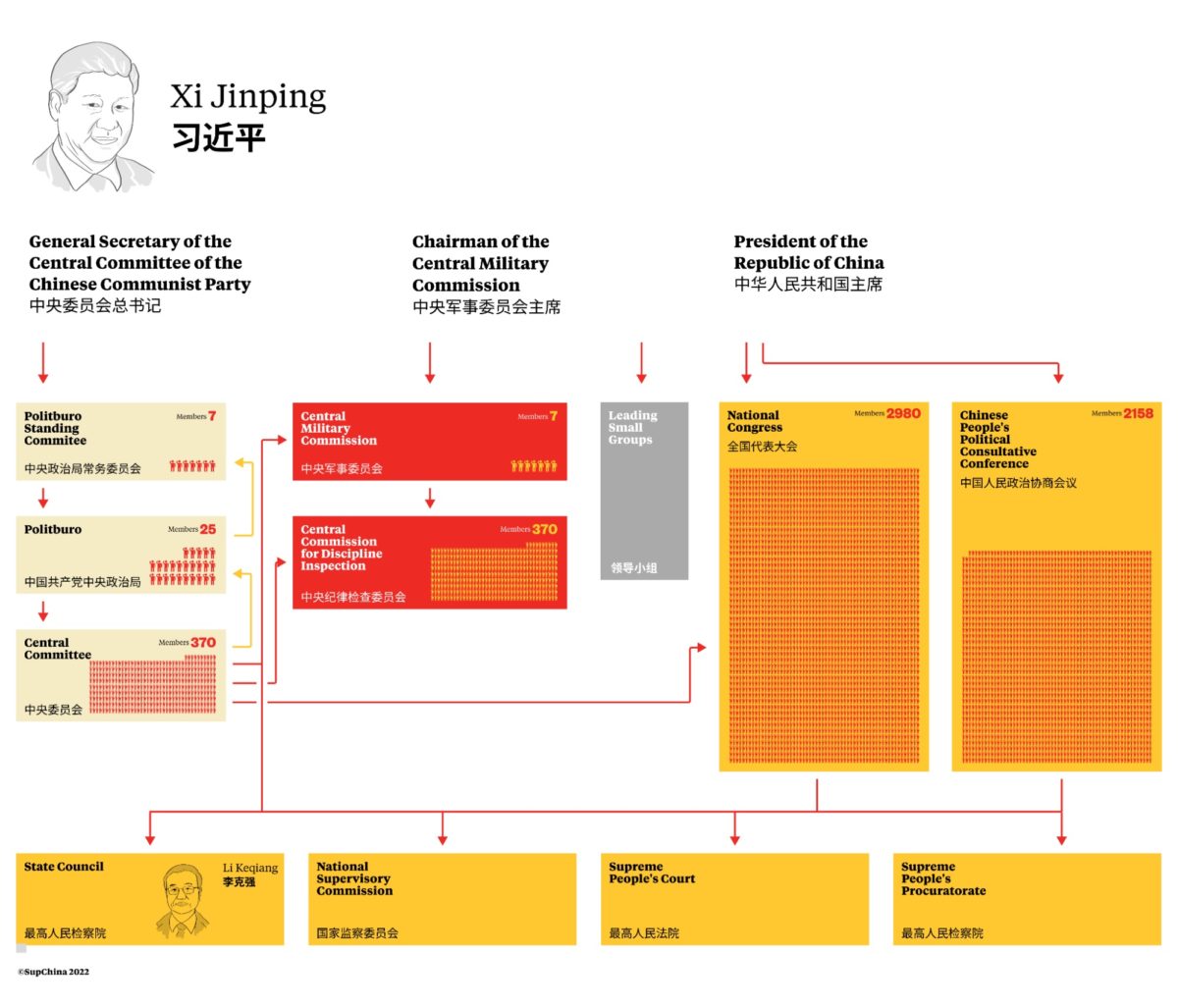

China’s political structure is simultaneously simple and dense. As we approach the Party Congress on October 16 — a monumental meeting in which Xi Jinping is expected to begin a third term as leader — let’s lay out some basics about the Chinese government.

The National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is held once every five years. Beginning October 16, the 20th edition of this “Party Congress” will see dreary policy announcements delivered to around 2,300 Party members “from all walks of life” and gathered from every corner of the country. Flags will be raised and saluted, many oaths sworn, and the legitimacy of the leadership reaffirmed.

Most importantly, after a week of closed-door sessions, new leaders will be presented to the world.

While leader Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 removed presidential term limits from China’s constitution in 2018, he will not be elected “president” at the Party Congress. That will likely happen at next spring’s People’s Congress, an annual meeting not to be confused with the Party Congress. In any case, “president” is perhaps the least significant of Xi’s titles — which we’ll explain in a bit.

Xi holds a triad of positions. Listed in order of importance, they are: Party General Secretary, chairman of the Central Military Commission of the Chinese Communist Party, and president. The Communist Party has never clearly defined term limits on any of its leadership positions, aside from the president, which is mostly used in talks to foreign media and foreign governments. The title is rarely heard in the actual corridors of power in Beijing, where the leader is known as “national chairman” (国家主席 guójiā zhǔxí).

Whatever the job title, Xi’s leadership of China is very real, and it is a position that makes him, by some reckoning, the most powerful man in the world. At October’s Party Congress, he is expected to begin his third term as Party General Secretary.

What does the Party Congress do, really?

Every five years, the Communist Party of China has a meeting, ostensibly to select the Party leaders, announce broad policy directions for the years to come, and provide renewed legitimation for the leadership.

In actuality, the script has been decided long in advance, and the Congress rarely contains anything that comes as much of a shock during a week of closed-door sessions in the Great Hall of the People at Tiananmen Square.

The Congress represents a changing — or continuing — of the guard. It is China’s election day, only without a public election. Barring catastrophe, the leadership will be set in stone for the next five years.

The exact date for the Party Congress changes every five years, but is always in the fall. October 16 is relatively early for a Party Congress, which seems to indicate that inner-party tensions have been eliminated.

While broader policy plans are unlikely to be changed, the composition of the new Politburo remains uncertain. Xi will also announce a replacement for Premier Lǐ Kèqiáng 李克强, China’s No. 2 leader, who is to retire in March.

The Party and the state, and the party-state

Unless you count the eight token parties that have occasional meetings in Beijing but have no political independence, China is a one-party state. And it is also a party-state. The Communist Party and the government are so intertwined as to be the same thing. There is no meaningful difference between their functions and powers.

The Party controls the government, not the other way around. Xi and Chinese state media frequently state that this is a very good thing.

Nonetheless, while the Party dominates all branches of China’s political system and has all the power, the bureaucratic machinery of the government is largely responsible for the implementation of laws and policies and for ensuring that the wheels of society continue to turn.

Let us take a closer look.

The Party

The Party has a pyramid structure with the general secretary, Xi, at the top. Then comes the Politburo Standing Committee (the seven most powerful politicians in China), the Politburo (25 members, determined by incumbent and retired members), the Central Committee (370 members), and the National Party Congress (around 3,000 members).

The CCP also heads the military. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is technically and practically the army of the Communist Party, not the army of the country.

In theory, the Party elects its leadership from the bottom up, but in practice, members of the Politburo are selected in closed-door negotiations. The Central Committee ostensibly elects the general secretary through a vote, and the National People’s Congress elects the Chairman of the Central Military Commission.

The state

The government is led by the president, a largely ceremonial post that Xi holds. The last time a general secretary was not also president was in 1993, when Yáng Shàngkūn 杨尚昆 was president while Jiāng Zémín 江泽民 was General Party Secretary. Jiang took over as president that same year.

The main government office is the State Council, mostly limited to economic policy and directed by the premier, currently Li Keqiang, who is also on the Politburo Standing Committee.

The president is appointed every five years by the National People’s Congress. The next president will be announced in March 2023. If Xi is still the general secretary at that time, as seems likely, he will probably continue as president.

Why is this such a big deal?

After Máo Zédōng’s 毛泽东 death and the havoc of the Cultural Revolution, Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 and his allies in the Politburo moved to a more collective style of leadership in an attempt to avoid repeating the disaster.

The Politburo Standing Committee, rather than simply the big boss, became involved in the decision-making processes. The 2007 Party Congress defined collective leadership as “a division of responsibilities […] to prevent arbitrary decision-making by a single top-leader.” The system was criticized for creating bureaucratic deadlocks and being ineffective. Xi has shown little love for the collective leadership approach.

In 1982, a new national constitution stipulated that the president should not serve more than two terms. Xi’s predecessors, Jiang Zemin (1989–2002) and Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛 (2002–2012), both served only two terms as head of government. In 2018, Xi changed the constitution to remove the term limit for the office of president. This would, in theory, allow him to remain state president indefinitely. The National People’s Congress rubber-stamped the change.

It is important to note that the Party constitution does not include term limits for the general secretary, though Jiang and Hu both stepped down after two terms in office. Xi has so far refused to nominate a successor.

Also see:

What role will age limits play at China’s 2022 party congress?

What makes Xi different?

Under Jiang and Hu, China’s political system was characterized by two competing coalitions. The Shanghai clique formed around Jiang. Hu, Jiang’s successor, was a member of another group associated with the Communist Youth League. Xi was not seen as belonging to either group.

Soon after taking charge, Xi purged many leaders of other factions, reducing the representation of different voices in the Politburo. Even Hu’s protégé, Lìng Jìhuà 令计划, who had been chief of the General Office of the Chinese Communist Party, was charged with corruption.

While Jiang and Hu mostly followed Deng’s doctrine of pragmatism, Xi has prioritized an ideological economic agenda and generous support for state-owned enterprises. Xi also has a very different relationship with the international world order.

While his predecessors were slowly integrating, Xi has fundamentally challenged the “liberal world order” and affirmed his desire to reshape it. He has expanded China’s economic reach through an ever-growing list of investments overseas, in particular infrastructure development across Asia and Africa, embodied by the Belt and Road Initiative. This, as well as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, has allowed China to greatly increase its sphere of influence.

What’s next for the chairman?

Not much is going to change in Xi’s economic and security policies. He believes he is leading the country to international prestige and escaping the middle-income trap. Domestic stability and Party stability are essential for him to achieve this. However, Xi’s purges, anti-corruption campaigns, and attacks on the private sector have made him enemies, some of whom may become more visible during the third term. We might need to prepare for political volatility.

Meanwhile, China’s economy is in bad shape, projected to grow just 3.5% this year. Forecasts for 2023 suggest the economy could weaken even more in the months ahead. According to Kevin Rudd, former Australian prime minister, this economic slowdown has been largely generated by Xi’s policies, though things are not exactly booming elsewhere.

As the CCP sources its legitimacy from economic prosperity, the inability to ensure employment and growth may become a problem. The unpopular COVID-zero policy must surely be rebranded soon. China’s aging population and shrinking workforce present unprecedented opportunities for economic hardship and public discontent.

Xi may want a third term, but whether he is capable of doing what needs to be done over the coming years is very much an open question. His recent decision-making has been hard to read. He may take a more radical turn during his third term, and attempt to tighten his grip on power even further, triggering infighting and resentment within the Party and the population at large.