Peterloo: Documenting a Massacre

On 16 August 1819, the military violently dispersed a peaceful parliamentary reform meeting addressed by the radical politician Henry Hunt. That afternoon at least 15 people lost their lives (3 later died of their injuries) and up to 700 more were injured by mounted yeomanry wielding sabres or were trampled underfoot by the panicking crowd. The shocking event was quickly dubbed ‘Peterloo’ in mocking reference to the Battle of Waterloo only four years earlier.

It was a bloody and pivotal moment in Manchester’s democratic history. The Government retaliated with the Six Acts which effectively closed down the reform movement. Yet, in the longer term, reaction against the tyrannical response to Peterloo confirmed the right of free speech, assembly and peaceful protest in British politics. Its relevance resonates through the centuries and across nations and political cultures.

The University of Manchester Library holds the most extensive collections of documents, pamphlets, books, handbills, placards and newspapers relating to the massacre and its aftermath. These have been digitised and can be consulted here.

Manchester underwent rapid changes during the first decades of the 19th century. It was the shock city of the Industrial Revolution. Cotton production sited in colossal mills generated great riches. Yet alongside the wealth sat squalor, overcrowding and poverty. Unemployment, high food prices and taxation led to tensions and dissatisfaction with Government. Mancunians were restless and attracted to the promises of radicalism.

- Placards and the propaganda battle

- Reactions

- Peterloo victims

- Mapping Peterloo

- Repercussions

- The Manchester Observer (1819–1822)

- Remembering Peterloo

- Additional Resources

- Discussion Points

Placards and the propaganda battle

In the weeks leading up to Peterloo the city magistrates and the radical campaigners waged a war of words using large posters that were prominently displayed in the places where people gathered. Those issued by the authorities warned the populace against attending ‘illegal meetings’ and urged them to ‘abhor [and] reject itinerant advocates of treason’. Whereas the radicals stressed the democratic rights of Englishmen to meet and discuss political rights. Those advocating political reforms were in heated disagreement with Tory loyalists who preferred the status quo. As with Brexit today views were polarised and bitter.

Take a look at the two handbills below — both addressed ‘to the inhabitants of Manchester’. At first glance these handbills appear identical. On closer inspection they show the arguments of opposing political factions, the reformers and the loyalists. Both claim to know what was best for the British people and viciously attack their enemies. It is difficult to know which was printed first but the two pieces of print are most definitely in conversation with each other! Note the early references to the ‘Manchester’ bee.

To the Inhabitants of Manchester … A Reformer’ and ‘To the Inhabitants of Manchester … No Reformer’ Placards, Manchester, 1819.

In the years following the French Revolution there were genuine fears of insurrection. In Manchester the magistrates and the local elite grew uneasy as the number of political meetings grew and groups of young men met on wasteland to practice drilling. By the summer of 1819 they had requested military and civil assistance and were prepared to squash any uprising. It was said that the Manchester Yeomanry sharpened their swords in the days before Peterloo.

The Yeomanry had to literally cut and hack a road up to the hustings and this they did through a people absolutely passive. No resistance of any kind was, or indeed could be, offered — The Examiner

Reactions

As news of Peterloo spread there was widespread anger and condemnation from all classes. The spectacle of unarmed civilians being cut down by mounted soldiers was chilling. The fact that women and children were amongst the victims fuelled resentment. Even those hostile to reform despised the brutality of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry.

The magistrates who sent in the military tried to avoid blame. Unluckily for them a journalist called John Tyas witnessed the atrocities from his seat next to Henry Hunt. Three days later The Times published his damning account. Criticism of the Manchester authorities by the leading newspaper of the day was damaging.

The brutality of the Manchester Yeomanry was condemned across the country. Rallies and meetings were held to discuss the atrocity. In Halifax, West Yorkshire, a vast out door rally was held on Skircoat Moor on the 4 October 1819 followed that evening by a dinner for 300 people. Here the speaker condemned the barbaric actions of the Manchester Yeomanry, pronouncing them unfit for civilised society.

Defenceless women seemed … the object against which their hostility was directed — Leeds Mercury

Peterloo victims

50,000 people were at Peterloo but we know most about the unlucky ones — the injured and killed. Significantly, those with the most grievous injuries tended to have carried something that enraged the Loyalists, such as red caps of liberty or banners. Women were disproportionately targeted by the yeomanry a fact much commented on by contemporaries. There was no permanent police force instead Special Constables were sworn in on the day and the magistrates relied on the volunteer Manchester Yeomanry to keep order. Many of those attacked knew the names of those who injured them including the account by William Cheetham below.

Two of the most powerful items in the Peterloo collection are a printed book ‘The Manchester Sufferers’ and a manuscript book, ‘The Peterloo Relief Fund Account Book’. Each volume carefully lists the names, age, gender, livelihoods and addresses of the victims, the injuries they sustained and the amount of money they received. These lists were created by Relief Committees established to offer financial support to the injured people and their families. These books humanise the story of Peterloo and move our thoughts away from numbers to real people.

Both books have been digitised and put online for the use of family and local historians. They are significant as they reveal the extent of atrocities and expose how the state deliberately down-played the number of killed and types of injuries sustained.

Mapping Peterloo

The relative positions of the various groups of people at Peterloo are shown in this map drawn for a booked published at the centenary (see below). As you can see, the magistrates were inside a building, safely out of harm’s way. The plan also maps the location of buildings present in 1919 including some landmarks still present today such as The Midland Hotel and The Friends Meeting House.

The key makes it clear not only where the key groups were situated but also the timings that fatal afternoon. It is particularly chilling that a mere 20 minutes lapses between the charge of the Manchester Yeomanry and the field being cleared (save for the dead and the dying). Imagine the panic as the people hemmed in by the building try to escape St Peter’s Field. Most injuries were caused by crushing by horses or the crowd.

Repercussions

The State was quick to vindicate the magistrates and the military and civil powers. In a letter sent 21 August 1819 the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth, conveyed the Prince Regent’s praise to the Manchester authorities thanking them for their ‘prompt, decisive and efficient measures for preserving the public tranquillity’. No one was ever held accountable for the killings and at the State Trial in York the following spring Henry Hunt and the other ringleaders were found guilty and sent to prison,

The public mood was much less forgiving and there was much revulsion at the thought of unarmed men, women and children cut down by sabres while attending a political meeting. Peterloo lingered long in the popular memory and the state was careful not repeat the mistakes made.

The Manchester Observer (1819–1822)

The radical newspaper the Manchester Observer is closely linked to the story of Peterloo. It was James Wroe, the Observer’s editor, who invited Henry Hunt to Manchester to speak in August 1819 and it was Wroe that coined the satirical and enduring nickname ‘Peterloo’. The Manchester Observer doggedly campaigned for justice for the victims and their families until it closed in 1822. It remains a key source for historians working on Peterloo. The entire run of the Manchester Observer has been digitised and is available here. You can key word search within each issue but not across the whole collection.

Remembering Peterloo

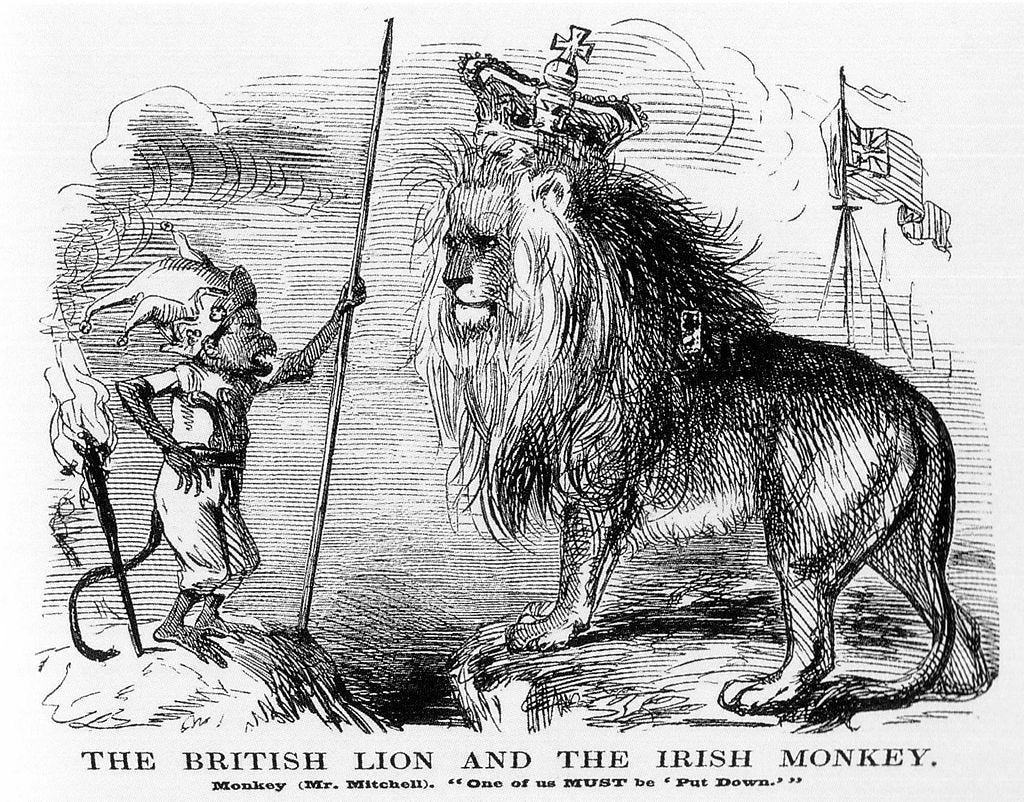

Peterloo provoked strong emotions. In the 19th century the massacre was immortalised in popular song, poetry, engravings, ceramics and caricatures. Isabella Banks, a popular Victorian author, wove Peterloo into her classic tale, The Manchester Man.

The bitterly satirical verse, The Political House that Jack Built, was composed in the immediate aftermath of Peterloo. It was written in the style of a nursery rhyme and spread knowledge of the atrocity in an accessible and memorable verse. The powerful illustrations were drawn by George Cruikshank. Note how the deeply unpopular Prince Regent was depicted as a strutting peacock who was apparently ‘unconcerned’ at events in the north (page 16 of the book reader).

The Romantic poet, Percy Shelley, on hearing news of events in Manchester, wrote a powerful poem called the ‘Masque of Anarchy’. In it he praises the non-violent stance of the Manchester protesters when faced with state aggression. The political situation was such it could not be published during his life time and it did not appear in print until 1832. Significantly that was the year of the Great Reform Act when Manchester finally got 2 MPs. Shelley’s Masque of Anarchy was, and remains, a highly influential poem. The poignant last stanza (below) still speaks to us today

The Masque of Anarchy: a poem Percy Shelley, London, 1832.

As part of the bicentenary events held at The John Rylands Library in August 2019 the actor Maxine Peake gave a reading of Shelley’s most famous poem which you can watch here

Special demonstrations of the Library’s Colombian printing press were also given as part of the exhibition events programme. You can watch below Jack Hardman (Visitor Engagement Assistant) print the first page of the ‘Masque of Anarchy’ and explain its significance to Peterloo and wider protest movements.

For years Peterloo was largely forgotten by the people of Manchester. It was an awkward and uncomfortable episode in the city’s history. The Victorian city dignitaries refused to include Peterloo in the Manchester Town Hall murals and in the 1970's local businesses, including the Midland Hotel resisted a bid to rename St Peter’s Street, ‘Peterloo Street’. Instead the campaigners were given a plaque which described only a gathering but not the injured. It would take further efforts by the Peterloo Memorial Campaign to get a more representative plaque;

200 plus years on, the campaign for a ‘respectful, informative and prominent’ memorial was finally achieved. In 2019 the Turner Prize-winner, Jeremy Deller, created a commemorative installation near the site of the massacre.

Additional Resources

There are several Peterloo blogs based on collections held at the University of Manchester Library

Schools

Free downloadable children’s version of the graphic novel Peterloo: Witnesses to a Massacre by Robert Poole, Polyp and Eva Schlunke

Books and articles

Samuel Bamford, ‘Passages in a Life of a Radical’ (1841). A vivid contemporary account by weaver and poet from Middleton. For a closer look at Samuel Bamford and other eye-witnesses to the Peterloo massacre click here

Isabella Banks, ‘The Manchester Man’ (1876). A best-selling novel which includes a detailed and vivid Peterloo scene informed by eye-witness accounts.

Robert Poole, ‘The English Uprising: Peterloo’ (2019). Poole is the undisputed authority on the Peterloo massacre. This book includes new evidence and interpretations

Graham Phythian, ‘Peterloo Voices Sabres and Silence’ (2018). A very readable account which includes reproduces many primary sources and encourages the reader to make their own minds up.

The Peterloo special edition of the ‘Bulletin of the John Rylands Library (BJRL)’, including Robert Poole’s, ‘The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper’, BJRL, 95:1 (spring 2019), 30–122.

For the spatial history of Peterloo see this article by the historian Katrina Navickas

Museums and libraries

Chetham’s Library, holds archives, books and newspapers.

People’s History Museum, has a permanent exhibition of Peterloo artefacts.

Working Class Movement Library holds printed resources and Peterloo artefacts.

Websites

Manchester Histories Festival website includes digitised Peterloo resources:

The National Archives holds an extensive amount of material on Peterloo:

British library has a useful article on Peterloo

Discussion Points

What do the injury lists tell us about the types of people present at Peterloo?

The Government of the day claimed that the 16 August 1819 was a riot. Do you agree?

Are there parallels with the radical social movements of the nineteenth century with those of today?

Images reproduced with the permission of The John Rylands University Librarian and Director of the University of Manchester Library. All images used on this page are licenced via CC-BY-NC-SA, for further information about each image, please follow the link in the caption description.