In the spring of 1981, a Rochester-trained physician made a discovery that would launch a new chapter in medical history.

Michael Gottlieb was just a few years out of his internal medicine residency at the University of Rochester when he made medical history as the first physician to identify and describe the disease that soon after became known as acquired immune deficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

“I remember those first patients in great detail,” Gottlieb told a Medical Center audience in November 2015. “I remember what they looked like. I remember certain mannerisms of those first patients in far greater detail than patients I saw last week. I remember the courage with which they faced the unknown.”

Gottlieb, who earned his MD in 1973 at Rochester before completing his residency training at the School of Medicine and Dentistry, was in his first year as an assistant professor of immunology at UCLA when he asked one of his fellows to look for some interesting teaching cases—the kind who had “immunologic features that might be interesting to talk about on rounds,” Gottlieb later recalled. The fellow brought him Michael: a 31-year-old man, healthy just weeks before, who had arrived in the emergency room reporting severe weight loss, loss of appetite, and a persistent fever.

Three months later, in April 1981, Gottlieb and his colleagues at UCLA had identified four cases similar to Michael’s, all in the Los Angeles area. Gottlieb noted a few things in common about the patients. They had all been healthy until recently, and they were all sexually active gay men.

“At first I thought the immune deficiency in these patients might actually be reversible,” Gottlieb told the same audience in 2015. “Our first four patients were gay men. Is it possible they had some common exposure to a drug or a toxin?” He wondered if the reversal might come about naturally, as the immune system recovered.

The patients continued to deteriorate, coming down with multiple infections. Gottlieb notified the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and in June, published a nine-paragraph report, “Pneumocystis Pneumonia—Los Angeles,” in the CDC’s newsletter, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The report was the first clinical description of AIDS. And for the purposes of tracking AIDS cases, the date of Gottlieb’s report—June 5, 1981—marks the official start of the AIDS epidemic.

Following a synopsis of each of the five patients, Gottlieb wrote in the report, “All the above observations suggest the possibility of a cellular-immune dysfunction related to a common exposure that predisposes individuals to opportunistic infections.” Tests on the patients showed infections present in semen, but not in urine, leading Gottlieb to speculate that “seminal fluid may be an important vehicle” of transmission.

Gottlieb’s brief report launched not only a new era in medical history, but also the arrival of what would become the physician’s calling. Gottlieb, who treated Rock Hudson following the actor’s explosive announcement in 1982 that he had AIDS, has continued to treat AIDS patients ever since. Cofounder in 1985 of the American Foundation for AIDS Research, Gottlieb has been a leading advocate for AIDS research and treatment for 35 years.

Much was still unknown following the identification of AIDS. It wasn’t until 1983 that French researchers discovered the virus HIV as the cause of AIDS.

For a long time, AIDS was also assumed to be primarily a disease of gay men in modern urban enclaves. Thirty-five years later, it’s well known that that’s not the case. Activist-led public education campaigns in the 1980s and 1990s proved remarkably effective in reducing HIV transmission in gay communities in the United States—although in 2001, those rates began to rise again. Today more than 9 out of 10 cases of HIV are among men, women, and children in developing nations.

More than 30 years, 78 million cases, and 35 million deaths later, Gottlieb is optimistic that AIDS can be overcome, most likely through a vaccine.

But it will also take more than even the discovery of a vaccine or a cure. Writing on the 25th anniversary of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, Gottlieb made an observation that’s no less true today: “I believe overcoming AIDS means extending our medical progress to everyone—and that’s a tall order.”

Read more

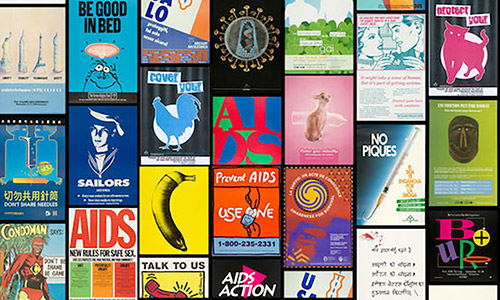

8,000 posters, one collection

8,000 posters, one collectionThe AIDS Education Poster Collection, housed in the Department of Rare Books, Special Collections and Preservation, is the world’s largest single online collection of visual resources related to the disease.

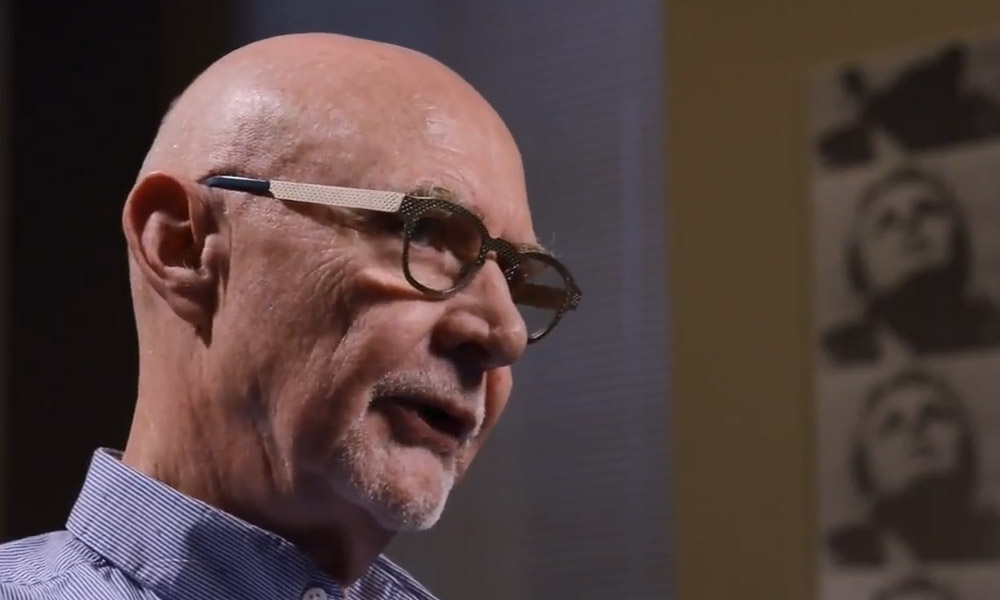

Representing AIDS, then and now

Representing AIDS, then and nowAlthough AIDS is no longer the subject of his work, art and cultural critic Douglas Crimp—the Fanny Knapp Allen Professor of Art History and a professor of visual and cultural studies—played a central scholarly role in the first two decades of the AIDS crisis.

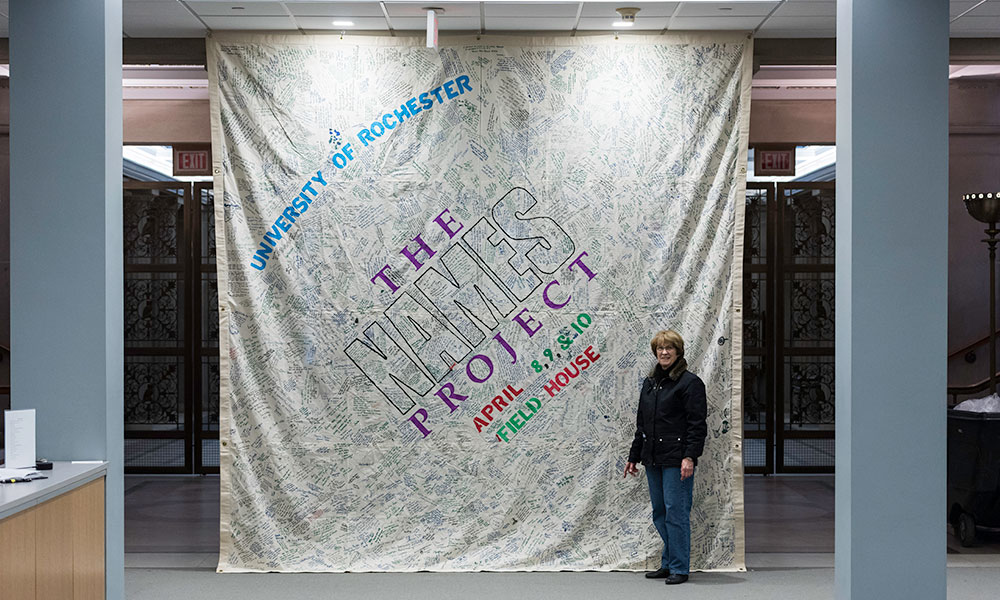

AIDS Remembrance Quilt resurfaces after 23 years

AIDS Remembrance Quilt resurfaces after 23 years“I knew I had it,” says Linda Dudman of the University Health Service. “I knew it was a very important item to keep, but I never quite knew what to do with it.” Now the 12-foot square panel will be on display through February and finds a new home in River Campus Libraries.