When You Take A DNA Test, This Happens

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

You've probably seen the ads on TV, YouTube, or just trolling your way through the internet telling you to take a DNA test and find out about your heritage. It seems pretty simple — you pay a small fee, they send you a kit, and the next thing you know you find out where in Germany your forefathers lived! Well, that's not exactly how it works. So what wizardry happens to figure out all those pie charts filled with countries you barely know anything about?

How this stuff actually works

If you tried to figure out what the story is with DNA and just found a bunch of nine-syllable words with a whole lot of Xs in them that sound remotely Latin, here's the easier version.

In the simplest terms, you have a genetic mom and dad — the egg and sperm that met up one day to form you, dear reader. It's from your parents that you get your DNA, half from your mom and half from your dad. However, parents don't pass down exactly the same DNA every time. That's why you only look a little like your sibling, unless you're an identical twin. (Identical twins share 99.9 percent of their DNA but let's just set them aside for now. Identical twins always make things confusing.)

To further break down how that whole "half from each parent" thing works, the DNA that does go to a child can sometimes be quite unexpected. A parent with both European and African DNA could end up passing on only their European DNA to one child and only their African DNA to another, which is what happened to twins in England, one black and one white, according to the BBC. When you think of DNA, just remember: You're getting 50 percent from each parent, you just don't know which 50 percent.

Let's look at the numbers

Still lost? Want hard numbers that acknowledge that life isn't always a 50-50 clean split? Fine, fine. Let's say you're 19 percent Italian. Your wife (or husband) is 0 percent Italian. It doesn't mean that genetically speaking your kids are automatically half of what you are. Rather, they could end up being 12 percent, 10 percent, and 3 percent Italian. It just means that of the 19% Italian you have, that's how much made it to them.

And it works the other way too. Let's say one parent has less 0.5 percent European Jewish DNA and the other has 1 percent European Jewish DNA. They could have a child with 1.5 percent European Jewish DNA — more than either parent. Basically, in the big soup bowl that is DNA that kid caught every bit of European Jewish DNA that could possibly make it their way. It's as random as a lottery.

You might find relatives you didn't know about

So let's say you end up purchasing a kit online. What exactly are you going to learn? After you spit in a cup or swipe your cheek or whatever, you can find a whole listing of relatives. Ancestry will provide you with a breakdown of family members based on shared DNA. Remember that whole "half each from your mom and dad" thing? Well, since your parents got half their DNA from each of their parents, and your grandparents (both sides) got half their DNA from each of your great-grandparents, you're bound to find some relatives you didn't know about (if they've used the same service you've used).

Orlando News 6 Anchor Lisa Bell shared how DNA located a half-brother she never knew. She and her half-brother, Rob, had each sent their DNA in to a service. Bell said she was adopted at age 2, but she knew that her birth father had other children. She also knew her birth father's last name and revealed that her DNA test showed a relative listed as "close family" with the same last name. That close relation ended up being her biological half-brother.

That's just one of many stories of people finding relatives; there are even people who found children that never knew they existed. For example, if your first cousin had a child they never knew about, and that child ran their DNA, they could match to you as a second cousin. And you could introduce the two and they could forge a relationship going forward. (That's what happened to this author.) So DNA is a great tell-all, right?

It's not a tell-all

Come on, get real. DNA doesn't tell you everything. For example, let's say you work your way back a few generations in genealogical research and come across a Native American connection. You decide to take the plunge and run your DNA to "confirm" your finding, and you end up being 100 percent European. What gives? Well, it turns out that DNA testing doesn't give you the complete picture. As Slate explains, a DNA test only looks at some of your DNA. That fancy chart that tells you that you're 19 percent Italian is really telling you that of the DNA they sampled, 19 percent of it is of Italian descent.

In other words, sometimes old pencil and paper (or internet search and grave finding) is more accurate than what genes were passed to you when it comes to heritage. Ancestry explains that you have less than a 1 percent chance of sharing DNA with a relative who is seven generations back. If you do some digging and come across a Native American ancestor from the 1600s but a DNA test doesn't confirm the connection, it's likely because genetically speaking the test didn't find that strand of DNA. Doesn't mean you're wrong, but that DNA might not be there anymore.

And what it shows you isn't exactly correct either

If you've seen some snazzy commercials advertising DNA results that will pinpoint the little village your ancestor came from, that's not how it works. That's not how any of it works. DNA can take your sample and match it to other people who have built family trees and narrow it down to regions, but that isn't a success because of your DNA. It's because of the family tree work. Still, DNA is usually pretty precise, except when it isn't.

Inside Edition tested DNA results with two sets of identical triplets and identical quadruplets. That means each group (not pictured) came from the same egg and should be genetically the same (or 99.9 percent the same). One set of triplets got rather unique results. One company gave them three different percentages for their French and German heritage: 11 percent, 18 percent, and 23 percent. Another company gave the other set of triplets three different English percentages. The rest of the results were more uniform.

One company explained that the results are presented in a sliding "confidence" scale from 50 to 90 percent. The higher the number, the less confident they are. In other words, that 19 percent Italian you got is "probably kinda right."

They can use your info as they please

The big double helix in the room is, "What exactly will they do with my DNA?" Paying with a credit card on the internet is risky enough, but having your DNA out there for anyone to clone is a bit too silly for most. DNA Explained points out that the big companies can do what they please with your info if you agree to their terms. And if you click that little check box to opt out, that's very courageous of you but it probably doesn't mean spit. (Although they probably will sell your spit to Big Pharma.)

In 2017, Ancestry set the record straight and stated that it does not "sell your genetic data to insurers, employers, or third-party marketers." (That leaves the door open for possible sales to others, though.) It did, however, admit that your DNA could be legally obtained. In November 2017, the Atlanta Journal Constitution reported that 23 And Me had refused to turn over five DNA samples to various law enforcement agencies. Ancestry, conversely, has previously turned over DNA in a murder investigation. If there's a proper warrant for your DNA, you probably shouldn't expect the service provider to fight too hard for you.

It might tell your medical future

There are other things that might pop up when you test your DNA. Besides finding cousins and kids you never knew about, your DNA can be used to measure medical probabilities. There are tests available that will let you know if you're a carrier for certain hereditary diseases. If you've inherited an abnormal BRCA gene, you could be at a higher risk for breast cancer. They can't diagnose everything yet, and the scope is currently very limited. But the prevention is real. Angelina Jolie wrote in a New York Times op-ed that genetic testing led to her preventative surgery. She had an 87 percent chance of contracting breast cancer, so she chose to remove both breasts preemptively.

DNA solves historical mysteries

You'll be hard pressed to name a better villain than King Richard III. Shakespeare made him into a hunchback. Does "now is the winter of our discontent" ring a bell? Well, Richard III was a real person and the last English monarch to die in battle. For centuries, no one really knew his final resting place. Then they found him in a parking lot. At least they thought they found him, but how could they be sure? Good ole DNA.

Based on a hypothesis, researchers dug at a location in Leicester where a church once stood before they paved that paradise and put up a parking lot. As CNN detailed, bones and teeth discovered there yielded DNA that potentially could lead to a match to confirm the person's true identity. Family tree experts located Michael Ibsen, who was a direct descendant of Richard's sister and a Canadian living in London, and scientists compared his mitochondrial DNA to the parking lot DNA. Mitochondrial DNA doesn't change much from generation to generation, so if you can find a complete line, even 600 years later, you can potentially find a match between two men — even if one of them lived before Columbus traveled to America. And that's exactly what happened. The DNA proved a match and confirmed that the bones discovered were indeed Richard III. He wasn't a hunchback either; Shakespeare just threw that in for some artistic flare. Richard III really had scoliosis, so take that, Bard!

DNA proves crimes

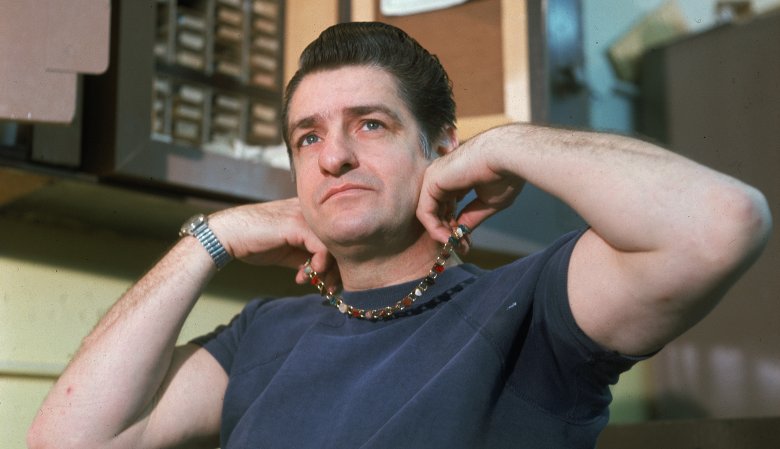

DNA not only solves historical mysteries, but can also assist in solving old crimes. Even if you know nothing about him, you probably know you should be a little afraid of the Boston Strangler based on his name alone. Albert DeSalvo ultimately went to prison for the Strangler murders in 1967, but there remained some doubt as to whether he committed the crimes or was simply a patsy. Author Susan Kelly theorized the Strangler murders were by more than one person. If she was correct, we know for sure who one of those killers was now.

Mary Sullivan was just 19 years old when she became a Strangler victim in 1964. The perpetrator left behind physical evidence at the scene, and astute investigators saved the evidence hoping technology would one day figure out how to tie it to someone. Well, 49 years later it did. As the National Institute of Justice explained, Y-DNA lifted from the crime scene matched a nephew of DeSalvo — giving investigators a 99.9 percent match. Given the implications, with a little time and DNA results, any old cold case with (uncontaminated) physical evidence could potentially be solved using DNA matching and bring closure to long-suffering families.

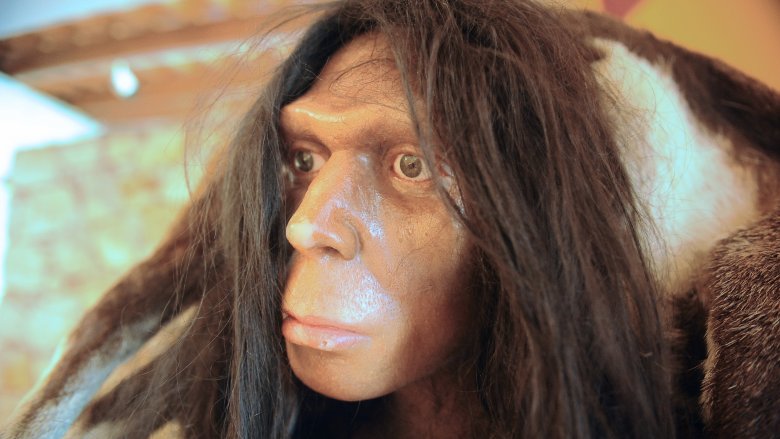

You might not be completely human

There are potential drawbacks to DNA testing, of course. It might show that you're something you didn't know you were. (Swedish!? Come on!) Or it might confirm what your ex always said: that you're not completely human.

As National Geographic explained, there was a time not too long ago when humans weren't the only hominids prancing around looking for woolly mammoths. Neanderthals and Denisovans were also on Earth, and the old-school humans bred with both groups. Today, people of European or Asian descent carry at least 2 percent Neanderthal DNA. (It's really just anyone who isn't of African descent.) One new theory is that the Neanderthals weren't killed off by early humans but were genetically absorbed, crossbred into extinction. Same thing goes for the Denisovans. The Melanesians, a group of Pacific Islanders, might find up to 5 percent of their DNA is Denisovan.

Everybody is related anyway

You know that jerk who cut you off in traffic? Take a DNA test and that could be your cousin. Heck, even without a DNA test, that's your cousin. The moron who won't scoot over on the subway? Her, too. That guy who talks on speakerphone in public? Yep. This is going to get a bit crazy, but it'll all make sense in the end.

You know how you have parents? Obviously, they had parents, too. Very quickly, you can get back to great-great grandparents. You actually have 16 great-great-grandparents you're directly related to. If you're American, there's a pretty good chance one of the eight great-great-grandfathers you have (or 16 great-great-great-grandfathers) fought in the Civil War. If you keep going back and doubling each generation after about 500 years, you'll hit a quandary.

Charlemagne (first Holy Roman Emperor, King of the Franks, tall) is a good stopping point. Charlemagne lived in the late 700s to early 800s A.D., about 1,200 years ago. By the time you get back about 40 generations, the time of Charlemagne, you have over a trillion direct ancestors. Earth had around 300 million people then, so by default if you're of European heritage, you're related to Charlemagne.

It gets even more specific. Everyone with English heritage can claim a king in their line. Practically everyone with British heritage is related to King Edward III, who lived in the late 1300s. One big royal family! Statistician Joseph Chang explained in a not-very-easy-to-read study that all Europeans actually share a common ancestor from around 1400. Not of European descent? No problem! You could be related to Genghis Khan, which is pretty awesome. The Atlantic explains that Europeans can also claim Muhammad as a direct relative, and everyone in the world is probably related to Nefertiti and Confucius. The Confucius line traces its roots back almost 80 generations, and is pretty proud of that, but if we're all related it maybe isn't so special.