World Economic Situation and Prospects: February 2023 Briefing, No. 169

The world economy faces multiple mutually reinforcing shocks

The world economy faces multiple mutually reinforcing shocks

A series of severe and mutually reinforcing shocks hit the world economy in 2022, as it approached the mid-point for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. While the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic continue to reverberate worldwide, the war in Ukraine unleashed a new crisis, disrupting food and energy markets and exacerbating food insecurity and malnutrition in many developing countries. High inflation is eroding real incomes, triggering a global cost-of-living crisis that has pushed millions into poverty and economic hardship. At the same time, the climate crisis is taking a heavy toll on many countries, with heat waves, wildfires, floods, and hurricanes inflicting massive humanitarian and economic damage.

These shocks will weigh heavily on the world economy in 2023. Persistently high inflation – which averaged over 9 per cent in 2022 – has prompted aggressive monetary tightening in many developed and developing countries. Rapid interest rate hikes by the Federal Reserve of the United States have triggered capital outflows and currency depreciations in developing countries, increasing balance-of-payment pressures and intensifying debt sustainability risks. Financing conditions have tightened sharply amid high levels of private and public debt, pushing up debt servicing costs, constraining fiscal space, and increasing sovereign credit risks. Rising interest rates and diminishing purchasing power have weakened consumer confidence and investor sentiment, further clouding near-term growth prospects of the world economy. Global trade has softened due to tapering demand for consumer goods, the protracted war in Ukraine, and continued supply chain challenges.

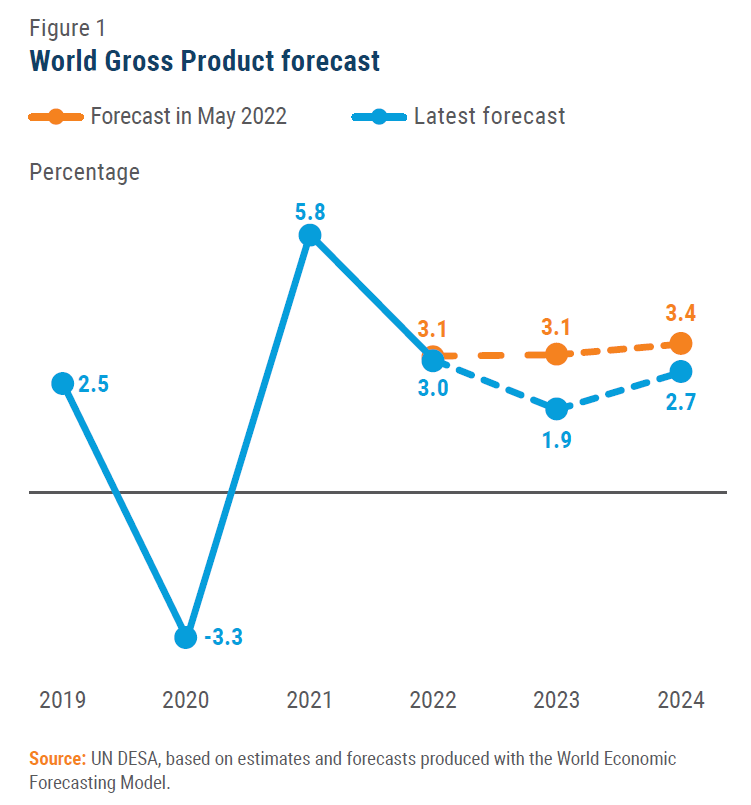

Against this backdrop, the world output growth forecast was revised down significantly from the May 2022 projection (figure 1). The world gross product growth is projected to decelerate from an estimated 3.0 per cent in 2022 to only 1.9 per cent in 2023, marking one of the lowest growth rates in recent decades. Global growth is forecast to moderately pick up to 2.7 per cent in 2024 should, as expected, some of the macroeconomic headwinds begin to subside next year. Inflationary pressures are projected to gradually abate amid weakening aggregate demand in the global economy. This should allow the US Federal Reserve and other major central banks to slow the pace of monetary tightening and, eventually, shift gears to a more accommodative monetary policy stance. The near-term economic outlook remains highly uncertain, however, as a myriad of economic, financial, geopolitical, and environmental risks persist.

Against this backdrop, the world output growth forecast was revised down significantly from the May 2022 projection (figure 1). The world gross product growth is projected to decelerate from an estimated 3.0 per cent in 2022 to only 1.9 per cent in 2023, marking one of the lowest growth rates in recent decades. Global growth is forecast to moderately pick up to 2.7 per cent in 2024 should, as expected, some of the macroeconomic headwinds begin to subside next year. Inflationary pressures are projected to gradually abate amid weakening aggregate demand in the global economy. This should allow the US Federal Reserve and other major central banks to slow the pace of monetary tightening and, eventually, shift gears to a more accommodative monetary policy stance. The near-term economic outlook remains highly uncertain, however, as a myriad of economic, financial, geopolitical, and environmental risks persist.

Sharp downturn in most developed economies

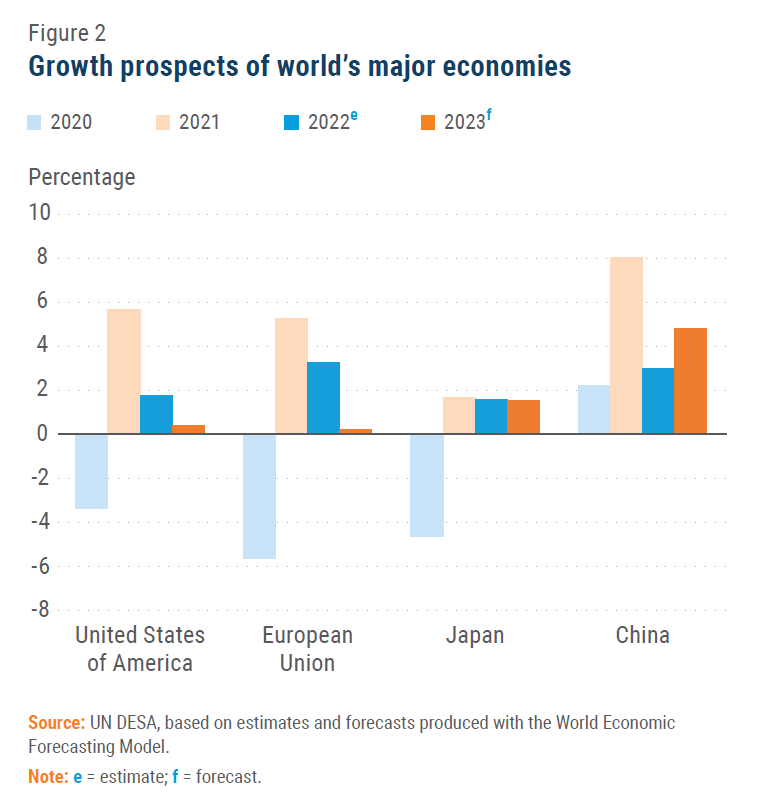

The current global economic slowdown cuts across both developed and developing countries, with many facing risks of recession in 2023. Growth momentum has weakened in the United States, the European Union, and other developed economies, adversely affecting the rest of the world economy. In the United States, GDP is projected to expand by only 0.4 per cent in 2023 after estimated growth of 1.8 per cent in 2022 (figure 2). Consumers are expected to cut back spending amid higher interest rates, lower real incomes, and significant declines in household net worth. Rising mortgage rates and soaring building costs will likely continue to weigh on the housing market, with residential fixed investment projected to decline further.

The short-term economic outlook for Europe has deteriorated sharply as the war in Ukraine continues with no end in sight. Many European countries are projected to experience a mild recession, with elevated energy costs, high inflation, and tighter financial conditions depressing household consumption and investment. The European Union is forecast to grow by an estimated 0.1 per cent in 2023, down from 3.2 per cent in 2022 (figure 2), when further easing of COVID-19 restrictions and release of pent-up demand boosted economic activities. As the European Union continues its efforts to reduce dependence on Russian fossil fuels, the region remains vulnerable to disruptions in energy supply and gas shortages. The prospects for the economy of the United Kingdom are particularly bleak given the sharp decline in household spending, fiscal pressures, and supply-side challenges, partly resulting from Brexit. After entering recession in the second half of 2022, GDP is projected to contract by 0.8 per cent in 2023.

Despite growing at a moderate pace, Japan’s economy is expected to be among the better-performing developed economies in 2023. Prolonged chip shortages, rising import costs (driven by a weakening Japanese yen) and slowing external demand are, however, weighing on industrial output. But, unlike in other developed economies, monetary and fiscal policy is still accommodative. Gross domestic product is forecast to increase by 1.5 per cent in 2023, slightly lower than the estimated growth of 1.6 per cent in 2022 (figure 2).

Despite growing at a moderate pace, Japan’s economy is expected to be among the better-performing developed economies in 2023. Prolonged chip shortages, rising import costs (driven by a weakening Japanese yen) and slowing external demand are, however, weighing on industrial output. But, unlike in other developed economies, monetary and fiscal policy is still accommodative. Gross domestic product is forecast to increase by 1.5 per cent in 2023, slightly lower than the estimated growth of 1.6 per cent in 2022 (figure 2).

The war in Ukraine heavily impacts near-term economic prospects for the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and Georgia, and neighbouring countries in South-Eastern Europe. The contraction of the economy of the Russian Federation, and the significant loss of output in Ukraine are having spillover effects on the rest of the region. Nonetheless, the Russian economy shrank less than initially expected in 2022, with GDP declining by only about 3 per cent due to a massive current account surplus, continued stability of the banking sector and reversal of the initial sharp monetary tightening. Several of the region’s economies benefited from relocation of businesses and residents and capital inflows, experiencing faster-than-expected growth in 2022. Growth in the region’s energy exporters was supported by improved terms of trade. Overall, aggregate GDP of the Commonwealth of Independent States and Georgia (excluding Ukraine) is expected to contract by 1 per cent in 2023, following an estimated decline of 1.6 per cent in 2022.

Worsening outlook in most developing regions

Growth in China is projected to moderately improve in 2023 after a weaker-than-expected performance in 2022. Amid recurring COVID-19 related lockdowns and prolonged stress in the real estate market, the economy expanded by only 3 per cent in 2022. With the Government abandoning its Zero-COVID policy in late 2022 and easing of monetary and fiscal policies, economic growth is forecast to accelerate to 4.8 per cent in 2023 (figure 2). But the reopening of the economy is expected to be bumpy, and growth will likely remain well below the pre-pandemic rate of 6 to 6.5 per cent.

Economic recovery in East Asia remains fragile, although average growth is stronger than in other regions. In 2023, GDP growth in East Asia is forecast to reach 4.4 per cent, compared to 3.2 per cent in 2022, mainly reflecting the modest recovery of growth in China (figure 3). However, many economies in the region (other than China) are losing steam amid fading pent-up demand, rising living costs and weakening export demand from the United States and Europe. This coincides with a tightening of global financial conditions, and countries adopting contractionary monetary and fiscal policies to curb inflationary pressures. Although the expected recovery of China’s economy will support growth across the region, a surge in COVID-19 infections may temporarily create negative spillovers.

In South Asia, the economic outlook has significantly deteriorated due to high food and energy prices, monetary tightening, and fiscal vulnerabilities. Average GDP growth is projected to moderate from 5.6 per cent in 2022 to 4.8 per cent in 2023 (figure 3). Growth in India is expected to remain strong at 5.8 per cent, albeit slightly lower than the estimated 6.4 per cent in 2022 as higher interest rates and a global slowdown weigh on investment and exports. The prospects are more challenging for other economies in the region, with Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka seeking financial assistance from the IMF in 2022.

In South Asia, the economic outlook has significantly deteriorated due to high food and energy prices, monetary tightening, and fiscal vulnerabilities. Average GDP growth is projected to moderate from 5.6 per cent in 2022 to 4.8 per cent in 2023 (figure 3). Growth in India is expected to remain strong at 5.8 per cent, albeit slightly lower than the estimated 6.4 per cent in 2022 as higher interest rates and a global slowdown weigh on investment and exports. The prospects are more challenging for other economies in the region, with Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka seeking financial assistance from the IMF in 2022.

In Western Asia, oil-producing countries have emerged from the economic slump, benefitting from high prices and rising oil output as well as the recovery of the tourism sector. Recovery in non-oil-producing countries, by contrast, has remained weak amid tightening access to international finance and severe fiscal constraints. Average growth is projected to slow from an estimated 6.6 per cent in in 2022 to 3.5 per cent in 2023 amid worsening external conditions (figure 3).

In Africa, economic growth is projected to remain subdued with a volatile and uncertain global environment compounding domestic challenges. The region has been hit by multiple shocks, including weaker demand from key trading partners (especially Europe and China), a sharp increase in energy and food prices, rapidly rising borrowing costs and adverse weather events. As debt servicing burdens mount, a growing number of Governments are seeking bilateral and multilateral support. Economic growth is projected to slow from an estimated 4.1 per cent in 2022 to 3.8 per cent in 2023 (figure 3).

The outlook in Latin America and the Caribbean remains challenging, amid unfavourable external conditions, limited macroeconomic policy space, and stubbornly high inflation. Regional growth is projected to slow to only 1.4 per cent in 2023, following an estimated expansion of 3.8 per cent in 2022 (figure 3). Labour market prospects are challenging, and reductions in poverty across the region are unlikely in the near term. The region’s largest economies – Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico – are expected to grow at very low rates owing to tightening financial conditions, weakening exports and domestic vulnerabilities.

New challenges for macroeconomic policies

Policymakers face difficult trade-offs in steering their economies through the current crises and supporting an inclusive and sustainable recovery. Macroeconomic policies need to be carefully calibrated to strike a balance between stimulating output and taming inflation, with effective coordination between monetary and fiscal policies minimizing the risks of a prolonged and severe economic downturn. Risks of policy mistakes are significant, especially since macroeconomic policy responses have limited capacity to address non-economic shocks. Policy missteps could aggravate economic downturns and inflict further socio-economic harm, especially on vulnerable groups.

Risk of overtightening monetary policy

Monetary policy is facing major challenges and trade-offs. Many developed country central banks, including the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank, were initially reluctant to raise policy rates, perceiving the rising inflation as transitory. As it became clear that inflationary pressures were more persistent and risked de-anchoring inflation expectations, they embarked on an aggressive monetary tightening path in 2022, raising rates at a very fast clip. Now, central banks find themselves at a critical juncture as economic prospects have weakened, while inflation is not yet fully under control and fiscal challenges remain. Rapid and synchronized monetary tightening by the world’s major central banks have pulled too much liquidity out of markets too quickly, generating significant negative spill-over effects on the global economy and weakening the economic prospects of the vulnerable countries.

Overtightening of monetary policy would drive the world economy into an unnecessarily harsh slowdown – an outcome that could be avoided if rate increases by individual central banks accurately considered the reciprocal impacts of similar rate hikes by others. This will require more effective coordination among major central banks, supported with clear policy messages to manage and moderate inflationary expectations.

The need to avoid fiscal austerity

Persistent fiscal deficits and elevated public debt levels have prompted calls for rapid fiscal consolidation even as recovery from the COVID-19 recession remains incomplete and fragile. But this is not the time for socially painful and potentially self-defeating fiscal austerity. On the one hand, fiscal retrenchment tends to be associated with painful cuts to social spending that disproportionately hurt the most vulnerable groups, including women and children. Public budget cuts often reduce or eliminate programmes and social services that benefit women more than men, creating income losses for women, restricting their access to health and education services, and increasing unpaid work and time poverty. Such impacts would further exacerbate the already dire situation of those who are yet to regain employment and livelihoods due to a weaker-than-expected economic recovery. On the other hand, an excessively early shift to austerity would stifle growth, delay recovery from the current crises, and undermine much-needed financing for sustainable development and fighting climate change.

Amid an increasingly challenging macroeconomic and financial environment, many developing countries are at risk of entering a vicious cycle of weak investment, slow growth and rising debt-servicing burdens. Any rapid fiscal consolidation, through significant expenditure cuts or tax hikes, would likely push economies into recession or lead to a protracted period of slow growth. This will worsen rather than improve debt sustainability in developing countries.

Fiscal expenditures, when properly directed, are particularly effective in supporting growth and development in times of economic slack due to large multiplier effects of public spending. In most developing countries, actual output is still below potential output, implying persistent economic slack. In the presence of such spare capacities and economic slack, public investments do not crowd out private investment but can instead be a powerful tool to create jobs and reinvigorate growth. Public investment not only boosts short-term aggregate demand, but also stimulates capital formation, expanding productive capacities and lifting potential growth. In the current context of high uncertainties, strategic public investment will signal policy commitment and likely crowd in private investment, which will remain critical for mitigating the scarring effects of the pandemic crisis. By expanding productive capacities, public investments can also lessen supply-side constraints and reduce inflationary pressures in the medium-term. As fiscal space is constrained in most countries, public expenditures need to be well-managed, targeted and efficient.

The current challenges demand a transformative SDG stimulus package, recently proposed by UN Secretary-General António Guterres. This would help offset deteriorating financing conditions and allow developing countries to scale up investment in sustainable development. The package addresses both short-term urgencies and long-term sustainable development finance needs, calling for a massive increase in financing for sustainable development, including humanitarian support and climate actions, through concessional and non-concessional funding.

Stronger international cooperation an imperative

The pandemic, the global food and energy crisis, climate risks and the looming debt crisis in many developing countries are testing the limits of the existing multilateral frameworks. International cooperation has never been more important than now to face these multiple global crises and bring the world back on track to accelerate progress towards the SDGs.

The world is at a critical juncture, as it approaches the midpoint of the SDG timeline. The financing requirements for developing countries to reach the SDGs and address the climate crisis have been estimated by a range of entities to be in the region of a few trillion dollars per year. Given the already limited fiscal space in developing countries, and growing needs for stimulating recovery and protecting the most vulnerable, these countries face significant challenges in making such investments. At the same time, favourable climate and SDG outcomes, even if realized through action in specific countries, can have significant positive spillover effects across the world. Hence, more robust international cooperation in mobilizing the resources needed to secure such outcomes are in the interest of all countries, both developed and developing.

Follow Us