Analysis of Poem 'West-Running Brook' by Robert Frost

West-Running Brook Summary and Explanation

West-Running Brook is a philosophical poem at heart written in the form of a dialogue between a young husband and wife. The brook is a metaphor for consciousness of a certain contrary type. It moves inexorably, the 'stream of everything that runs away.'

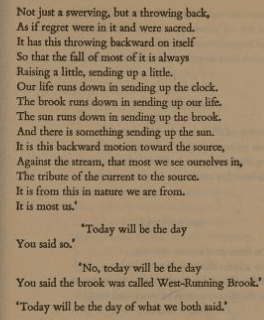

Frost's wedded couple offer contrasting views on the nature of the brook, which itself has a wave running counter to its flow. The man, Fred, forms a swift analogy between the contrary nature of the brook and their own relationship as individuals—he puts it down to trust. But then he asks rhetorically, 'What are we?'

The woman, who is not named, replies 'Young or new?' and goes on to explain just what it is that's caused the wave that runs counter to the brook itself, initially spotted by her husband.

So, it's a west-running brook when all other brooks run east to the sea. And a counter-wave within its flow, sent back by a sunken rock. There's a sense of puzzlement and potential discovery as the married pair feed off each other.

There is also some mild tension in the dialogue; we can picture the couple wondering about their future together as the brook flows on westward, not toward the sea, opposing logic, confusing yet offering a new challenge.

In Summary

- The poem focuses on the individual responses to this contrariness, both in nature, metaphysics and the couple's relationship. West is the material, the flesh, the abyss, death.

- The brook is the flow of life's flux (carrying all matter) as it moves with time.

- The counter-wave, caused by a sunken rock, represents individual spirit and consciousness. It can also be seen as emotional energy resisting, a struggle against the flow.

- The husband initially takes a fixed rational approach to the wave and the brook, but later seeks to understand the origins of existence and inevitable decay. His monologue suggests that this resistance, this sending up, back towards the source, is that most we see ourselves in.

- The wife is more open to change and ideal and brings a spiritual element when thinking about the wave and brook. She is the tender to Fred's tough. She has the first line and the last.

- In the end, both are reconciled to the idea of two individuals inextricably a part of all things, which includes being contrary.

Influences of the Poem

As with many of Frost's longer poems of a philosophical nature, they are often inspired by ideas he gleaned from both the natural world and the written work of thinkers, both historical and contemporary.

With this particular poem two prominent names are known to have influenced the creation: William James (1842–1910), American philosopher and psychologist, and French philosopher Henri Bergson (1859–1941).

Frost was inspired by William James's books, Principles of Psychology (1890), Pragmatism (1907) and perhaps Is Life Worth Living? (1895) and The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902).

The poet particularly admired the pragmatist in James—he said that James was the best teacher he'd never had, having read many of his books—and it is clear that Frost gave Fred in the poem the pragmatist's role: tough-minded and skeptical. In contrast, the wife is tender-minded and leans toward the spiritual.

Henri Bergson's book Creative Evolution (1911), which Frost read, contains an image that could have been used as the basis for the poem:

'Life as a whole, from the initial impulsion that thrust it into the world, will appear as a wave which rises, and which is opposed by the descending movement of matter.... this rising wave is consciousness.... [Individual souls] are nothing else than the little rills into which the great river of life divides itself, flowing through the body of humanity.' (Creative Evolution, pp. 269-70.)

It seems that Frost created the central image of the poem having absorbed these philosophical ideas—he then wove the dialogue of the newlyweds around and through the metaphor.

How successful this form is in 'West-Running Brook' is open to debate. Some think the interaction between Fred and his wife lacks authenticity; the philosophical idea is too heavy for them to carry off successfully. Other scholars suggest that there is a valid balance between discourse and idea, that syntax and meter work well enough for the reader. (Contrast Frost's 'Home Burial' poem, which also has a powerful husband and wife dialogue.)

Frost was a great admirer of the American poet and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) and must have known of his use of metaphorical language in such publications as 'Nature' (1836), an essay outlining transcendentalism, where the natural world is seen as a 'precipitation' of the mind. The element water plays a significant role:

'Man is a stream whose source is hidden.' ('The Over-Soul')

Emerson also wrote on the nature of poetry:

'It is not words only that are emblematic; it is things which are emblematic. Every natural fact is a symbol of some spiritual fact...Who looks upon a river in a meditative hour and is not reminded of the flux of all things?'

In one sense, 'West-Running Brook' could be a short scene from a play directed by all three philosophers, written inimitably by Frost, who loved nothing more than a quirk of nature to kick-start his muse and create 'a momentary stay against confusion.'

An Ambiguous Theme

Some might argue that this poem only adds to the confusion, for the reader at least. Perhaps this is the legacy of some of Frost's more ambiguous poems—they remain open-ended and ripe for questioning and debate.

In 'West-Running Brook' there are no definitive answers. The poem begins with a simple question from the woman and ends with her single statement, a joint statement in effect.

Between the first and last lines, Fred wants them to build a bridge across the brook, then teases his wife with lady-land before suggesting that resistance is what life is all about, part of a sequence of sending up that extends from the temporal to the mysterious.

Frost was definitely one to pit his will against the flow of things. He said:

'Every poem is an epitome of the great predicament; a figure of the will braving alien entanglements.' From 'The Constant Symbol', an essay by Robert Frost in Atlantic Monthly, October 1946.

This poem was published in the book West-Running Brook in 1928. The version below is the authentic original form of the poem.

Line-by-Line Analysis of 'West-Running Brook'

Eighty-two lines in all, many with that familiar Frostian beat of the iambic (laced with the odd trochee, pyrrhic, spondee and anapaest) carried on ten syllables. Because it is in dialogue form some lines are shorter—three or four syllables for example—but the next line often makes up the full 10. So it is a blank verse poem with a twist.

Lines 1–12

The opening line is a straightforward question from the wife, who asks for direction north from Fred. This in itself is a pointer to the sub-theme—where are they going this wedded pair?

At this early stage of the dialogue, Fred knows the answer. North is that way (does he gesture?) and the brook is running west. Now the reader can picture them, in a rural setting near the coast, observing the brook.

But this is no ordinary flow of water. The wife names it then Fred gives a rough summary of its contrary nature. All the other brooks run east, to the ocean, but this one flows in the opposite direction.

The brook is anthropomorphized, given human qualities. Fred addresses it rhetorically, puzzled as to why it should be going in such a direction. He guesses that the brook must be trusting of itself but then goes on to suggest that this is in some way just like them, they trust each other to be contrary, going against each other.

He tries to reason why this is but stumbles at that word because . . . because what? He's looking for some sort of definition of them both as a partnership.