China’s man for all seasons Wang Yang stops short of premiership glory

- Wang, political advisory chief and former vice-premier, was once a top contender to succeed Li Keqiang as China’s No 2 leader

- Exclusion from Central Committee line-up means his days on the political stage will end before he reaches retirement age

Once considered a front runner for the role of China’s premier, Wang Yang – head of the country’s top political advisory body – is set for full retirement instead next March.

His name was notably absent from the newly released list of top Communist Party leaders who will steer the country for the next five years.

Wang, 67, chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, was the fourth ranking official on the current Politburo Standing Committee, the party’s top decision-making body, as well as a former vice-premier.

Retirement awaits China’s Li Keqiang and Wang Yang as Xi builds third term

The Central Committee, which now seats 205 full members and 171 alternate members, groups the most powerful party leaders. Exclusion from it means certain exclusion from the next 25-member Politburo, China’s highest policymaking body, the line-up for which will be made public on Sunday.

This means Wang will step down alongside fellow 19th Politburo Standing Committee members Li Keqiang, Li Zhanshu, 72, and Han Zheng, 68, and enter full retirement – despite still being a year short of the customary retirement age.

While the ongoing party congress will decide on the leadership and party hierarchy, changes in key government posts – including that of premier – will be confirmed in March.

Wang was once widely seen as a leading contender for premiership, given his depth of experience in domestic governance and diplomatic roles. He was also liked across party power bases, including by Xi himself.

How Shanghai party chief could beat tradition to become China’s next premier

The question, however, was not whether Wang was the right man for the job but rather whether he would want such a tough job, according to Dali Yang, a political scientist at the University of Chicago.

“He has the experience and the gravitas to be the premier, but it is a very difficult job when Xi is such a dominant party leader who controls the levers of power,” Yang said.

In his 10 years at the top, Xi has elevated a wide range of leading groups to party commissions and made himself the chair of these commissions, including groups that oversee finance and economics.

And while the premier is the head of the State Council, or China’s cabinet, most ministries have a direct reporting line to the party.

“It’s almost like a chaotic role for the premier because the major decisions are taken by the party side essentially,” Yang said.

Analysts said Wang was a man for all seasons who demonstrated flexibility, a quality that saw him earn favours as he leaned from right to left along the party’s ideological spectrum throughout his career.

But Wang’s retirement effectively has opened up another seat into which Xi can fill a younger candidate that had directly worked under him in the past.

Bigger-than-expected changes loom as Xi shapes China’s top leadership

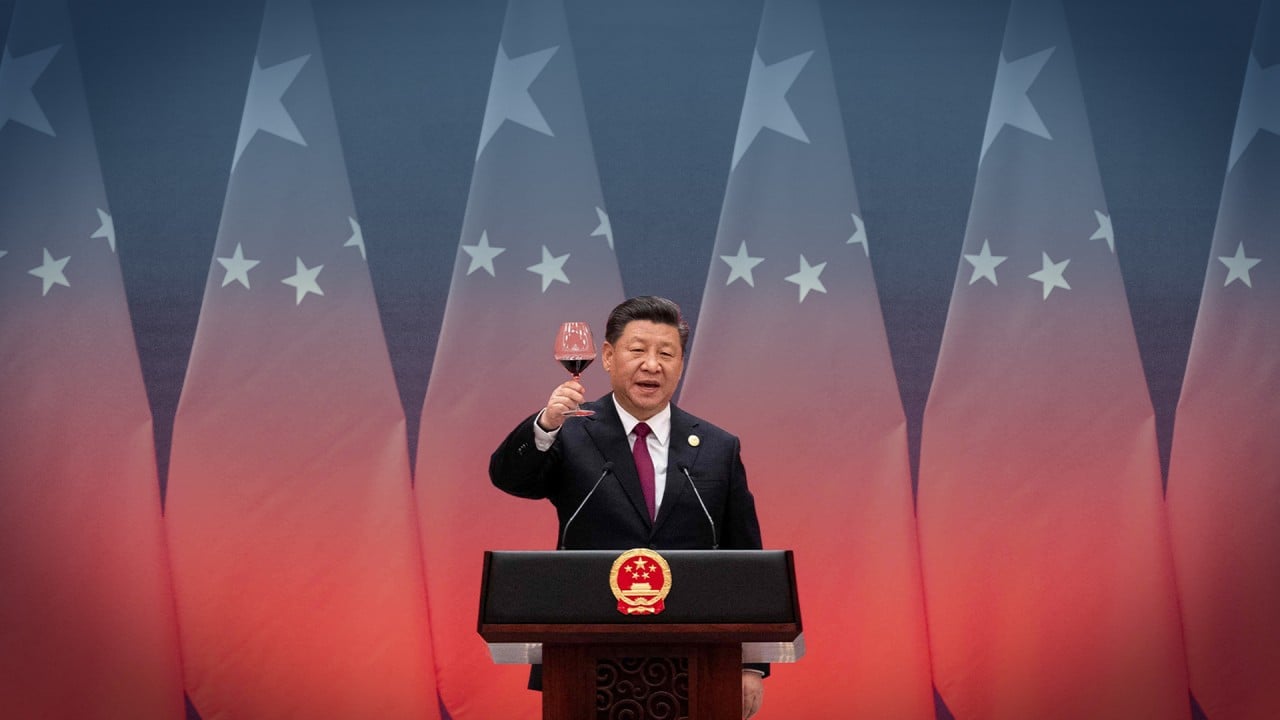

Wang’s confident, charismatic and easy-going manner set him apart from the cold and aloof image of Beijing officials in general. This earned him more praise in the international arena when, as vice-premier from 2013 to 2018, he was also China’s point man on Sino-US trade ties, involving frequent contact with the American Treasury and commerce secretaries.

As his career progressed to the national level, with being named vice-premier in 2013, Wang, showed himself to be a charismatic diplomat at economic summits with his US counterparts, including Jacob Lew, Treasury secretary under president Barack Obama.

During a meeting with Lew in 2013, Wang compared US-China relations to a marriage, where the cost of divorce would be too high, such as that between media tycoon Rupert Murdoch and Wendi Deng, the quip pointing to a lighter side rarely seen in public from Chinese leaders.

Upon promotion to the seven-member Politburo Standing Committee in 2017 under Xi, Wang became the top national official to oversee hard-line party policies on ethnic issues in Xinjiang and Tibet, and guided the Sinicisation of religious affairs while holding an outreach portfolio to engage non-party influential Chinese both at home and abroad.

“He is essentially a chameleon, someone without strong connections in high places. Even though he was liked by [former premiers] Zhu Rongji and Wen Jiabao, they did not provide staunch career support. So the only thing he could count on was cultivating good relationships with everyone,” said Bo Zhiyue, a New Zealand-based expert in top-tier Chinese politics.

“Who he really is doesn’t matter because he is a politician and self-preservation comes first in politics. This is a matter of survival.”

Born in a rural Anhui family with no links to the chambers of power, Wang dropped out of school at 17 to work in a food factory, to support the household after his father died.

He later studied political economy at the Central Party School in the 1970s and rose to become a lecturer there at a time when paramount leader Deng Xiaoping was launching his historic economic reforms.

Wang’s humble beginnings contrasted with those of the so-called princelings, the well-connected children of former party leaders or military top brass, such as Xi himself.

Xi Jinping, Mao and the question of legitimacy to rule China

However, help in his early career came from his father-in-law, a municipal official, said Yang Zhang, assistant professor at the American University’s school of international service.

Wang also impressed Deng during an inspection trip to Anhui and gradually worked his way up to become the mayor of Tongling in Anhui in 1989 and then one of the youngest vice-governors of the province in 1993, at the age of 38.

“Wang demonstrated his flexibility, opportunism and competence, both as a provincial and ministerial official. He maintained a very good relationship with high-ranking officials, including then premier Wen Jiabao when he served as deputy secretary general in the State Council,” Zhang said.

He was subsequently promoted to party chief of Chongqing municipality in 2005 and Guangdong in 2007, before being elevated to vice-premiership in 2013.

During his time in Guangdong, Wang was hailed as a liberal reformist as he worked to resolve months-long violent protests against corruption ripping through the eastern fishing village of Wukan in 2011. Even the party mouthpiece, People’s Daily, called his Wukan fix an act of “political courage”.

“Being liberal means very different things for those Chinese officials. They may perform different styles of governance in different roles. Wang is very flexible and certainly knows how to play this game,” Zhang said.