High Culture: The Visayans Before Spanish Colonization Were Badasses

There is this misconception of precolonial Visayan culture. It's this image of the noble bagani who is attuned to the spirits of nature and wears little more than a bahag—a symbol of the past that is almost fantastical, a romanticized glimpse from pop culture.

We have to remember that the Visayans of 1521, and consequently, the ones of Legazpi’s time 40 years later, were more than generic Western stereotypes. They were real people with a rich culture and diverse interests. And, to be honest, they were pretty badass.

Also read:

Historic Documents From the Federal State of the Visayas Resurface

Looking Back at the Time When Ancient Visayans Terrorized China

Visayans were feared and respected as warriors.

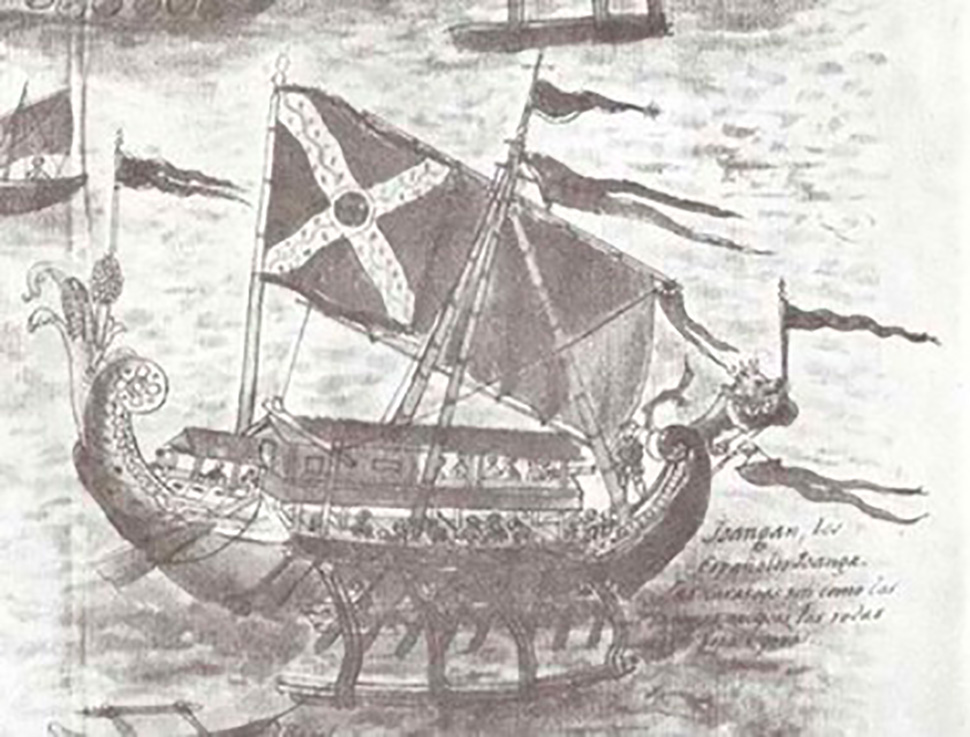

War and virility were very much central to the pre-colonial Visayan culture. The Visayans were seafarers and raiders who attacked each other or, more often than not, other islands near the archipelago. Their most common targets were the Moros and the Maranao people of Mindanao, though it wasn’t strange for them to reach as far north as Luzon either. An account from Legazpi talked of how Rajah Suleyman of Tondo saw the Visayans as fierce warriors only to become weak under Spanish influence.

The Visayans saw warfare as an initiation rite toward manhood, and this was shown in their tattoos. Men showcased tattoos to boast of their valor, while women had tattoos for their “conquests” in sex. Men who had killed an enemy additionally showcased their feat by wearing a red bahag, as well as a red turban (magalong). Additional feats lengthened the magalong.

Visayans practiced unique body modification.

Aside from tattoos, which led the Spanish to called them pintados, the Visayans also had a lot of practices modern society would consider strange. One of the most prevalent tradition was decorating their teeth black by chewing anipay root or applying a tar-based coating called tapul. They also chewed betel nut, ant eggs, or kaso flowers to paint their teeth red.

Another way they modified their teeth was by filing them, sometimes removing half the tooth in the process. The aim was to make the teeth look symmetrical and even. But perhaps, the most impressive example of Visayan dentistry was in decorating their teeth with gold. Generally, the Visayans looked down on the Spanish and their unmolested teeth. Not only were they mapuraw (untattooed), but their teeth were unchanged like a monkey’s. Truly shameful.

Aside from decorative dentistry, the Visayans also practiced skull molding, conforming with standards of beauty at the time. They considered broad faces with receding foreheads and flat noses to be desirable and compressed their babies’ skulls accordingly. They used a tangad to compress the baby’s forehead to force it to grow higher.

Visayans lastly took special care of their special areas, as well. Men would use pins to augment their weapons and provide better stimulation for their partners. They were small bars of metal pierced in the head, which anchored a sort of cogwheel with teeth. Try to imagine that for a while.

Visayans were top class drinkers.

Aside from fighting and, uh, fornication, Visayans were known as hard drinkers. The Spanish detested meeting with Visayans because they wouldn’t discuss anything without a drink, and they saw it as “attempts to subvert their occupation.” But Visayans were not alcoholics—they detested being drunk in public and they had a sophisticated drinking culture.

Drinking was a social event that was done for anything and everything, from official work to family gatherings and community decisions. It was called pagampang or conversation and usually began with an agda, an exhortation to a person or a diwata to take the first shot.

They also had a lot of options for their choice of drink. Visayans had tuba, rice wine strengthened and dyed red with wood bark; distilled tuba or other spirits called alak; a fermentation of wood bark and honey called kabarawan, which they drank communally from a jar through straws; intus, a wine made from sugarcane juice; and pangasi, rice wine reserved for formal occasions and ceremonies.

Visayans followed a complex religion.

Visayans took their religion seriously. Far from simple devil or nature worship, Visayan religion was an intricate series of rituals and belief systems that guided the lives of the people. They believed that celestial bodies, like the stars and the moon, were objects of reverence, with the cycles of the moon and the constellations corresponding with the agricultural cycle.

Visayans believed in an unseen world full of malevolent creatures that the Spanish called engkantos and dwendes. The unseen world was the home of the diwatas, gods that they consulted as part of their daily life. There was a diwata to explain almost anything. For example, Dalikmata, with its many eyes, was the cause of eye ailments, while Makabosog caused men to be gluttons. Cebuanos referred to the image of the Sto. Nino as “The Spaniard’s diwata” and immersed it in water in times of drought.

But perhaps the most supreme of the gods was Bathala Maycapal, similar to the Tagalog supreme god. The people of Negros and Bohol had different gods though—theirs was Lalahon or Laon, the creator god that resided in Mount Kanlaon.

To commune with the gods or with ancestor spirits called umalagad, the Visayans consulted the babaylan. They were shamans who were granted the special ability to commune with the diwata. The babaylan could be male or female or even male transvestites called asog, and were integral parts of the community. They did not need to work in the fields but were instead sustained by taking a share from the religious offerings or paganito.

Visayans were poets and musicians.

Today, we only know glimpses of pre-colonial Visayan life through academic sources and secondhand accounts by Spanish chroniclers. A large part of why there is a lack of primary sources is because Visayans spread their traditions orally.

There was a Visayan alphabet, though there is dispute if it was different or similar to the Tagalog baybayin. Regardless, they didn’t use their alphabet for literature. That’s not to say Visayan literature didn’t exist. Visayan speech was full of prose and metaphor, and Visayan poetry was filled with colorful imagery with its own poetic vocabulary.

Visayan poetry was usually sung or chanted, leaving little distinction with songs, and Visayans were noted for their love of song. Professional bards were sought after at weddings and festivals and were given a payment called bayakaw.

A Visayan verse was called ambahan, which was an unrhymed seven-syllable couplet whose two lines could be interchanged and still make sense. Ambahan was used in balak, a poetic debate between a man and a woman on the subject of love, accompanied by musical instruments. The more literary form of verse was the siday or kandu, which took at least six hours to sing and was full of heavy metaphors and talked about heroic exploits of ancestors or exaltations to living heroes.

The kandu was the basis of the Visayan folk epics that we enjoy today. Some of the more famous epics which have survived into modernity are Labaw Donggon, Kabungar and Bubung Ginbuna, and Datung Sumanga and Bugbung Humasanun, which weaved supernatural phenomena with heroic exploits, giving us a glimpse of Visayan life through the lens of the people who lived in it.

This is just a small glimpse of what the Visayan culture was—a diverse and complex mix of traditions, cultures, and norms. For a society gripped by centuries of colonialism and semi-colonial rule, it pays to look back at our past and appreciate just how rich we were and still are.

Sources:

Scott, William. Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Eugenio, Damiana. Philippine Folk Literature: the Epics. University of the Philippines Press.

Blair and Roberston. The Philippine Islands 1493-1898. University of the Philippines.