You are here

| Title | Date | Date Unique | Author | Body | Research Area | Topics | Thumb | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Okinawa Factor in Japan–China Relations | August 04, 2023 | Arnab Dasgupta |

On 3 July 2023, a delegation of 80-odd members of the Japanese Association for the Promotion of International Trade, led by former House of Representatives speaker Yohei Kono, visited Beijing for a four-day trip to meet with senior Chinese officials.1 Among the delegation was Denny Tamaki, Governor of Okinawa prefecture, Japan’s southernmost set of islands. During the visit, Tamaki paid his respects at the collective grave of people from his prefecture interred on the outskirts of Beijing. The graves are of people who died due to various causes during the later half of the Qing dynasty (1636–1911).2 Tamaki then headed to Fujian province in the south of China, where he met local Communist Party officials, including the governor of the province.3 After returning to Japan, he expressed satisfaction with his visit, and prayed for good relations to continue. Okinawa’s Complex HistoryOkinawa was originally known as Ryukyu (Luchu to the Chinese) and was an independent kingdom under its own government. In the 15th century, the kingdom rose to prominence as a trade hub between the Japanese and Chinese empires, and entered into tributary relations with both Ming China and later the feudal samurai lords of the Satsuma domain (presently Kagoshima prefecture) in Japan. China’s goalsIt is these anxieties that China wishes to exploit. By cultivating a sense that Okinawans are an independent entity, the Chinese may be able to stoke opposition to the bases, and embolden anti-base activists to oppose the facilities more stridently. They could also encourage the Okinawans to seek alternative sources of investment and trade from Chinese sources in order to counter the tight financial control exercised by Tokyo, enabling Okinawa to stand up to the latter in matters of national security. Should Japan oppose this or place artificial controls on Okinawan investment, China could easily make the case that Japan’s control of the islands is coercive after all, and help to dent Japan’s image in the eyes of the international community, as any controls would effectively violate Japan’s democratic norms. ConclusionIf Okinawans’ genuine concerns are to be assuaged, an acknowledgement of Japan’s ethnic diversity would go a long way. The government made a good start in 2019 by acknowledging through legislation that the Ainu community of Hokkaido are the indigenous inhabitants of Japan.10 A similar legislation that notes Ryukyu’s independent history and acknowledges mainland Japanese assimilation policies as oppressive would take the sting out of several points of criticism. Additionally, in order to prevent the base issue from festering, Japan could consider moving a sizeable number of US bases out of the prefecture to other places around the Japanese mainland. Doing so would not only lighten the burden currently borne by Okinawa, but also improve national security, as dispersed bases in multiple locations would make it harder for China to launch missile strikes against them. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

East Asia | China-Japan Relations | system/files/thumb_image/2015/china-japan-t.jpg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Changing State Perception of Nuclear Deterrence in Japan and South Korea | August 03, 2023 | Abhishek Verma, Arnab Dasgupta |

SummaryJapan and South Korea face the combined threat of an increasingly assertive China and a progressively more destabilising North Korea, not to mention a Russia which has resumed its role as a Pacific power. The US has enhanced its engagement with its East Asian partners in nuclear planning and consultation mechanisms. The prospects of indigenous nuclear weapons acquisition by Japan and South Korea, though, cannot be ruled out. IntroductionIn 2021, after Prime Minister Fumio Kishida came to office, Setsuko Thurlow, an atomic bomb survivor and well-known anti-nuclear weapons activist, urged him to sign the newly-negotiated Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).1 She blamed the Japanese government for seeking continued protection from the very weapons that had been twice used on its soil by the very power that now guaranteed Japan’s security. She urged Prime Minister Kishida to sign the treaty and lead the campaign against nuclear weapons. Japan however did not sign the TPNW and the nuclear umbrella of the United States remains intact. The nuclear programme of North Korea continues to churn, with little to no oversight by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Russia, the world’s largest nuclear-armed state, continues to threaten the deployment of tactical weapons against Ukraine. China modernises its arsenal and refuses to participate in arms control talks until the US and Russia reduce their arsenals first.2 Kishida’s hesitation to sign the TPNW and commit to a non-nuclear stance reflects the threat perception held by East Asian democracies such as Japan and South Korea, as they face the combined threat of an increasingly assertive China and a progressively more destabilising North Korea, not to mention a Russia which has resumed its role as a Pacific power. Evolving Nuclear PolicyHistorically, Japan and South Korea were early adopters of norms against nuclear proliferation. Japan is a signatory to all major international treaties relating to nuclear weapons (with the exception of the TPNW), as is South Korea. However, in the immediate post-war period, both had very divergent views on nuclearisation. Japan aligned itself closely to a staunchly negative stance towards nuclear weapons, while South Korea attempted to actually pursue its own domestic nuclear weapon, even as both were protected by the extended nuclear deterrence umbrella of the US. After 1945, as Japan slowly recovered from the war, its new constitution forbade it from possessing and maintaining any war-making capacity other than the bare minimum required for national defence. The US–Japan Mutual Security Treaty (called the Nichibei Anpo in short in Japanese), guaranteed the security of Japan by posting on Japanese soil a substantial number of forces who would, it was assumed, provide the offensive edge in the event of a conflict with the emerging Communist bloc. Nuclear weapons were part of the bargain, though there was significant hesitation on the part of the Japanese to reveal the existence of nuclear-armed forces in Japan. This instinct was further confirmed in 1954, after the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (Lucky Dragon No. 5) incident, when there was a huge outcry in Japan against the US and Russia’s ongoing nuclear weapons tests. This led then Prime Minister Eisaku Sato to declare the cornerstone of Japan’s stance on nuclear weapons: the Three Non-Nuclear Principles. Under these, Japan would not allow possession, production or storage of nuclear weapons (by the US) on its soil. Since then, despite the constant transit of US nuclear-armed submarines across Japanese waters, as well as the presence of the nuclear-powered US Seventh Fleet in Yokosuka Naval Base, Japan continued to maintain that its territory would remain free of nuclear weapons. It was partially these assurances which enabled it to become the only NPT non-nuclear signatory to possess the complete fuel cycle facilities necessary to reprocess uranium control rods from civil reactors into the high-yield variety capable of producing nuclear weapons. South Korea had a different trajectory, one which led it to attempt to produce its own nuclear weapon in the 1970s. After independence from Japan, the Koreans were immediately embroiled in the Cold War due to the presence of Soviet and US troops along the 38th parallel bisecting the country. The Soviet-supported state, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), then invaded the weaker and less developed south, which under US control had become the Republic of Korea (ROK) in 1950, leading to the Korean War. This three-year conflict, which ended with the division of the country in 1953, resulted in the new ROK finding itself adjoining a Communist dictatorship that was perpetually attempting to destabilise it. Therefore, the military junta in power at the time under President Park Chung Hee decided that despite US security guarantees, the presence of US troops on Korean soil, and the extended deterrence provided by the nuclear umbrella, the ROK needed to have its own weapon3 . In 1970, US President Richard Nixon’s declaration that the US would withdraw its troops from the Korean peninsula caused the South Koreans to set up the Weapons Exploration Committee4 , which explored ways of obtaining, processing and manufacturing enough high-yield plutonium to make weapons. The fall of South Vietnam in 1975 further heightened Korean anxiety, and hastened the development project. However, by 1975, the US, which had caught wind of the secret programme, pressured France to refuse to supply the necessary equipment, and the programme was shut down, though sporadic efforts continued till 19795 . By 1975, the ROK had signed the NPT, and placed its nuclear facilities under the IAEA inspection mechanism. In 1991, President Roh Tae-Woo emulated Japan’s example and issued the Five Non-Nuclear Principles: the ROK would not manufacture, possess, store, deploy or use nuclear weapons.6 At the same time, the US removal of tactical nuclear weapons from the South led to gradual public support for a nuclear deterrent of its own culminating in the present majority support for hosting nuclear weapons on its soil. Altered Threat PerceptionNorth Korea’s rapid nuclearisation, and the rise of China to great power status have altered these countries’ threat perception. It was already well-known that North Korea possessed the wherewithal to manufacture nuclear weapons. In the 1970s and 1980s, Abdul Qadeer Khan started a network that explicitly (with the connivance of the Pakistani government) marketed nuclear fuel processing equipment and expertise that could only have been used in a nuclear weapons programme to North Korea.7 North Korea’s march to nuclearisation continued, and in 2006 it tested its first nuclear weapon. Despite United Nations sanctions, the North continued to develop its nuclear capability further, leading to the persistent missile tests that have become such a common sight today. The initial response to North Korea’s tests were to conduct dialogue. The Six-party Talks8 , comprising the US, Japan, South Korea, North Korea, China and Russia, were intended to convince the North to give up its weapons in exchange for food aid, security guarantees and international recognition. However, the North Korean regime’s insistence on US forces being withdrawn from East Asia entirely, and its refusal to subject its nuclear facilities to IAEA inspection, doomed the talks to failure. Since then, North Korea has made increasingly belligerent threats of annihilation towards South Korea followed by repeated missile tests as well as further nuclear tests in 2009, 2013, 2016 (twice) and 2017. A far more concerning threat, however, comes from China. After developing a nuclear weapon in 1964, China quickly developed thermonuclear weapons with the assistance of the Soviet Union, and in 1967 conducted its first test of that more dangerous weapon. Since then, it has maintained a strategic arsenal of more than 400 weapons. While China has signed the NPT as a nuclear weapon state, it has not signed the CTBT. China maintains a No First Use (NFU) policy, though statements by Foreign Ministry officials in recent times have indicated that NFU may be waived against certain opponents, such as India and Japan. Another concern altering threat perceptions is the fact that an aggressive China under President Xi Jinping has recently declared significant expansion of its nuclear assets, after refusing to participate in US–Russia talks on reducing the nuclear weapon stockpiles held by both countries.9 Japan and the ROK have responded cautiously to the security threats and provocations emanating from North Korean missiles tests and Chinese excesses. The barrage of missile tests last year by North Korea, continuing well through this year, have necessitated fundamental realignment in the traditional security structures the ROK and Japan have long relied on. The strategic documents released by Japan and the ROK in December 2022 and June 2023 respectively have amply reflected these realignments in light of acute provocations from the North as well as the systemic challenge posed by China. Japan’s Response to Contemporary Security ChallengesJapan faces several regional and extra-regional security threats as reflected in the National Security Strategy (NSS) document. Chinese military activities in the Indo-Pacific region, both normatively and empirically, have “become a matter of serious concern for Japan and the international community.”10 With the ambition of “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”, China has increased its defense expenditure and has embarked on enhancing and modernising its nuclear and missile capabilities. China has intensified unilateral activities in East and South China Sea as well as Sea of Japan altering the status quo in and around Senkaku Islands in the Sea of Japan. The issue of Taiwan also inextricably impacts the security dynamics of Japan. Evidently, a missile entered Japanese exclusive economic zone (EEZ) when a missile launch demonstration was conducted by China during Taiwan Strait crisis last year. Hence, China presents a long term, credible and enduring security threat. On the other hand, North Korea presents an immediate security threat in terms of missile and nuclear provocations. There have been instances of cruise and ballistic missile tests conducted by North Korea including some of the missiles being launched over Japanese territory or falling within the EEZ of Japan setting off evacuation alarms across Japan. In yet another provocative steps to enhance its offensive military capabilities, North Korea made a failed attempt to launch first military surveillance satellite in June this year. Earlier in March 2023, before the ‘Freedom Shield’ joint exercise between South Korea and the US, North Korea warned in a statement that if the US took military action against the North’s strategic weapons test, it would be seen as ‘declaration of war’. Further, Kim Yo Jong, the sister of the North Korean leader, stated that “the Pacific Ocean does not belong to the dominium of the US or Japan.”11 The taboo of not threatening the use of a nuclear weapon appears to be diluting, which will have an inevitable impact on East Asian security dynamics. The threat of the use of nuclear weapons has continuously been issued in the ongoing Russia–Ukraine war. The importance that the Sea of Okhotsk plays in Russian strategic nuclear forces doctrine further multiplies their activities in Northern Japan. Joint naval drills and joint flight of strategic bombers with China appears to be yet another challenge, further amplifying the insecurity among the regional states. In order to address these challenges, Japan has prioritised the US–Japan alliance as the core of their strategy. Further, Japan’s recently unveiled National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy provide for reinforced capabilities including counterstrike and reconsideration of US-conceived integrated deterrence. Dramatic advancement in missile-related technologies including hypersonic weapons have rendered Japanese ballistic missile defences insufficient. It is for this reason that the NSS 2022 proposes adoption of counterstrike capabilities in effective coordination with missile defense systems. In what the document calls ‘flexible deterrence option’, it clarifies that first strike is impermissible. To advance these objectives, Japan is slated to increase its defence budget to 2 per cent of GDP by 2027. The challenge for Japan can be summarised in 2 Ds—deterrence and disarmament. Under Prime Minister Kishida, who hails from Hiroshima, the government’s solemn commitment to disarmament is quite conspicuous. His government’s aggressive approach towards disarmament is shaping both governmental and non-governmental discourses. On one hand, Kishida spearheaded the establishment of the 15-member International Group of Eminent Persons for a world without nuclear weapons.12 In February 2023, the group convened their second meeting which recommended three main action points—reinforcing and expanding norms; concrete measures on nuclear risk reduction; and revitalising the NPT’s review process.13 Kishida also took a group of most industrialised G7 members (including Ukrainian President Volodmyr Zelenskyy) to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park as a part of 2023 G7 Summit schedule. To set the discourse against the use of threat of nuclear weapons, as a part of G7 outcome documents, ‘G7 Leaders’ Hiroshima Vision on Nuclear Disarmament’ was also released.14 At the same time, Japan’s reliance on the United States’ extended nuclear deterrence presents a dichotomous situation wherein the US nuclear umbrella cannot be diluted due to its regional security implications, while the discourse around effectuation of disarmament must also be continued. Amidst the advancing nuclear and ballistic missile tests, including missiles launched by Beijing and Pyongyang last year in and over Japanese territory, Washington’s deterrence commitments have become more important than ever before for Tokyo. South Korean Response to Contemporary Security ChallengesThe security threat from Pyongyang is more acute in Seoul. Traditionally, under the US security umbrella, South Korea has increasingly found the alliance architecture insufficient to deter the North’s provocations. Since last year, North Korea has conducted over 120 cruise and ballistic missile tests as a response to the trans-Pacific alliance between the US and its East Asian partners. In past years, the North Korean threat of deployment of tactical nuclear weapons and preemptive nuclear strikes has further strengthened the multi-dimensional US-ROK security alliance. Besides the threat of North Korean Weapons of Mass Destruction, convergence of strategic interest between China and Russia, as also the unfolding great power competition between the US and China, present eminent challenges for South Korean security interests. Acknowledging the emerging threats—including the adverse impact of the Russia–Ukraine War, the Yoon Suk Yeol Administration came up with a new National Security Strategy (NSS) in June 2023. The document underlines the solidification of extended nuclear deterrence in the ‘Washington Declaration’15 which entailed the establishment of a Nuclear Consultation Group, deployment of US strategic assets and commitment to extended nuclear deterrence. It further details a South Korean ‘three axis system’ to tackle North Korean nuclear and missile threats based on three stages of confrontation—preemption, defense strategies and retaliatory strategy (Figure 1). These are Kill Chain strategy, Korean Air and Missile Defense (KAMD), and Korean Massive Punishment and Retaliation (KMPR) respectively. Kill Chain strategy aims to preemptively destroy North Korean nuclear and missile assets in case of clear indication of their intention to use nuclear weapons. Hence, it relies upon sophisticated surveillance and reconnaissance assets, along with precision strike capabilities. KAMD is a complex, multi-layered defence system that is designed to detect and intercept various types of missiles. KMPR aims at punitive massive retaliation with overwhelming force in order to deter North Korea and convey that the repercussion of its first strike would be so overwhelming that any perceived benefits from a first nuclear strike would be outweighed. ConclusionThe presence of the US extended nuclear deterrence to Japan and South Korea has ensured stability in the East Asian region for decades. However, deterrence has increasingly been diluted ever since the acquisition of nuclear weapons by North Korea in 2006. While domestic debates on nuclear weapons gained urgency given Chinese and North Korean provocations, South Korean President in January 202317 called for the deployment of US nuclear weapons or development of an indigenous nuclear weapon capability. The US has responded by enhancing engagement and integration of its East Asian partners in nuclear planning and consultation mechanisms. With increasing North Korean nuclear and missile threats, and Chinese nuclear force modernisation, the prospects of indigenous nuclear weapons acquisition by Japan and South Korea cannot be ruled out. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Terrorism & Internal Security, East Asia | Nuclear Deterrence, Japan, South Korea | system/files/thumb_image/2015/nuclear-missile-t.jpg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DDoS Attacks and the Cyber Threatscape | August 01, 2023 | Rohit Kumar Sharma |

SummaryDDoS attacks are posing a formidable challenge than ever before, due to technological advancements and other facilitating factors. When combined with other form of cyberattacks, the impact of disruption multiplies, leading to severe consequences for digital infrastructure. IntroductionIn June 2023, Microsoft identified increased traffic against some services that temporarily impacted availability to the company’s flagship office suite, including the Outlook email, OneDrive file-sharing apps, and cloud computing platform. On investigating the brief interruption, Microsoft identified a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) operation orchestrated by a threat actor that the company tracks as Storm-1359.1 Despite the sophistication involved in the operation, Microsoft assured customers that there was no evidence of unauthorised access to customer data. The company concluded that the threat actor appears to be focused on disruption and publicity. Within hours of the outage, a group named ‘Anonymous Sudan’ took responsibility for the attack on its encrypted Telegram channel with a message ending with, “We hope you enjoyed it, Microsoft”.2 DDoS Attacks and EnablersDDoS attacks are a form of cyberattack that render websites, servers, and other services inaccessible to legitimate users by overwhelming them with more traffic than they can handle.3 The perpetrators in such attacks attempt to exhaust network, server, or application resources to make them unavailable to legitimate users. In the event of a DDoS attack, a website or service is flooded with a barrage of HTTP requests and traffic, which originates from a coordinated network of bots known as a botnet.4 There are several types of DDoS attacks that are carried out by using different attack vectors. DDoS attacks have existed for decades; nevertheless, their prevalence has surged exponentially in terms of volume and intensity, owing to many factors. Threat actors are no longer limited to ‘computer geeks’ or ‘script kiddies’ but constitute sophisticated and organised groups with varying motivations. Advancement in technology has also been an enabler in amplifying such cyber incidents. The ubiquity of digital devices such as the Internet of Things (IoTs) has increased the threat landscape of DDoS attacks. The widespread adoption of digitalisation has expanded the attack surface, while the persistent problem of inadequate cybersecurity measures continues to persist. Another facilitating factor that has contributed to the rise in the frequency of such attacks is the ready availability of DDoS attack services, which is narrowing the gap between skilled and amateur hackers. Not that this is a new phenomenon of the underground market, as illustrated in 2016 report detailing the underground hackers market. The report noted that providing DDoS remains a popular service hackers offer on the underground market.5 The report also pointed out that most of these hackers were willing to perform a free 5 to 10 minutes DDoS test for customers and even charged higher if the target website had anti-DDoS protection installed. The black market also provides rented botnet infrastructure to execute DDoS attacks. MotivationThe motivation behind DDoS attacks varies with threat actors; hacktivists may use it for ideological reasons, cybercriminals for financial motives, and states for larger geopolitical reasons. According to an assessment, the DDoS threat landscape in the first half of 2022 was dominated by geopolitical events, with the financial sector being the most targeted segment.6 The ideologically driven APTs such as pro-Russian ‘KillNet’ and pro-Ukrainian were not only targeting the opposing nation with DDoS attacks but also countries and organisations seen to be supporting those nations. The most notable event was when the Vatican City website was knocked offline by a DDoS attack, allegedly by a group sympathetic to Russia.7 Another major geopolitics-driven attack was against the key Taiwanese websites by China-state-backed threat actors at the time of Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan.8 Occasionally, DDoS attacks were carried out to extort ransom payments, colloquially known as Ransom DDoS (RDDoS) attacks. The RDDoS attack should not be mistaken for ransomware, which may be driven by similar motivations but employs different tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). The operational method in ransomware requires ‘denial of data’ by a malicious script, whereas RDDoS involves denial of service, generally by a botnet.9 Running a ransomware operation requires access to internal systems, which is not the case in ransom DDoS attacks. In RDDoS, threat actors leverage the threat of denial of service to conduct extortion, which may include sending a private message by email demanding ransom amount to prevent the organisation from being targeted by a DDoS attack.10 According to a threat intelligence report, throughout the 2020–2021 global RDDoS campaigns, attacks ranged from few hours up to several weeks with attack rates of 200 Gbps and higher.11 The DDoS attack can also serve as a means of reconnaissance, allowing attackers to assess the target’s vulnerabilities and gauge the strength of its defenses. Lately, these attacks have been incorporated into triple extortion ransomware strategies, where data is not only encrypted and exfiltrated, but in case the ransom fails, the attackers may initiate a DDoS attack on the targeted services to intensify their operation.12 The Case of Anonymous SudanAnonymous Sudan best exemplifies the re-emergence of DDoS as a form of weaponisation of cyberspace to achieve varying objectives. According to reports, Anonymous Sudan emerged on 18 January 2023 and swiftly initiated its operations aimed at Sweden within a week.13 The group initiated cyber attacks against the Swedish government and companies in response to what it considered anti-Islamic actions in Sweden. Driven by ‘religious’ motivations, the group subsequently decided to focus its efforts on targeting Denmark and France. Upon creating its Telegram channel, the Anonymous Sudan account initially engaged in minimal activity, primarily expressing its objective to target “enemies of Sudan”.14 The account also shared posts amplifying the activities of Russian hacktivists groups such as KillNet and Anonymous Russia. Reportedly, on several occasions, the group has undertaken operations in tandem with other threat actors. For instance, in May 2023, Anonymous Sudan and an Iranian hacking collective known as Asa Musa (Persian for Moses Staff) made a failed bid to sabotage Israeli rocket alert applications during an episode of violence between Israel and Palestinian Islamic Jihad.15 In another incident, Anonymous Sudan, alongside KillNet (a pro-Russia hacker group) and REvil (notorious for ransomware attacks), unveiled their plans for attacks on the US and European Banking systems on their Telegram channels.16 A few days later, the European Investment Bank confirmed a DDoS attack affecting its operations without attributing the incident to any threat actor. However, the group claimed responsibility for the cyber incident on its Telegram channel. To date, the group has targeted many countries, including Australia, Germany, Israel, India, and the US. These countries have experienced attacks across various sectors such as government institutions, educational establishments, financial institutions, airports, and healthcare facilities. Motivation and Modus OperandiAnonymous Sudan has gained notoriety for engaging in DDoS attacks and defacing websites during its nearly six months of existence. The group asserts that it operates from Sudan and is involved in cyber activism, commonly referred to as hacktivism. The group’s claims and announcements provide significant insight into the ‘social’ and ‘political’ motivations driving their operations. Nevertheless, some assessments indicate a potential association between Anonymous Sudan and the pro-Russian hacktivist collective known as KillNet.17 Others suggest that the group is likely a state-sponsored Russian actor pretending to be motivated by Islamist ideologies. Based on its operational pattern and choice of target, the group initially appeared as a threat actor driven by religious motives. The group also asserted its affiliation with the larger Anonymous collective, which gained prominence in the early 2000s by instrumentalising digital activism to advocate for societal and political transformation. However, a detailed report on the group refuted this claim and indicated a potential connection between the group and the Russian hacker collective ecosystem. Other cyber threat intelligence firms have also reaffirmed the presence of a Russian connection in their assessments. Another sign of its close association with Russian threat actors, if not directly with the state, is the use of Russian language in its official Telegram channel alongside Arabic and Persian. During a recent interview conducted via Telegram, a ‘representative’ of Anonymous Sudan shared some intriguing insights with the interviewers. Due to the group’s tendency to seek publicity and make sensational claims, however, caution must be exercised before fully believing their assertions. On being inquired about TTPs, it was revealed that the group tailor the plan of action depending on the target, which may vary from Layer 4 attack to Layer 7 attack based on requirements.18 Refuting the allegations of being part of Russian cyber military campaign, Anonymous Sudan asserted that the accusations were unfounded. Interestingly, the interview was abruptly ended when questioned about the group’s self-proclaimed role as the defender of Islam while also demonstrating inaction against China’s persecution of one million Uyghurs . Lately, the group seems to have shifted from presenting themselves as politically-motivated hacktivists to using extortion tactics for financial gains.19 According to reports, the group demanded US$ 3 million from Scandinavian Airlines (SAS) to halt DDoS attacks against the airline’s website. The underlining reason behind the shift is uncertain, but the group appears to be well-funded. Rather than employing networks of infected or compromised computers to launch attacks cheaply, the group opted for a different approach. For targeting infrastructure in Denmark, the group rented 61 servers located in Germany from IBM Corporation’s SoftLayer division to carry out their operations.20 By doing so, they effectively concealed their activities behind multiple layers of anonymity. Even in the recent Microsoft outage, it was observed that the attacks likely relied on access to multiple virtual private servers (VPS) in conjunction with rented cloud infrastructure.21 Also, it is highly improbable for a grassroots hacktivist collective to utilise paid proxy services for carrying out their attacks, revealing subtle indications of the state’s involvement in guiding their operations.22 Attacks in IndiaAfter drawing attention to its ‘religiously’ motivated attacks in the Western world, the group shifted its focus towards targeting Indian infrastructure. The attacks specifically targeted airports, hospitals, and other critical infrastructure.According to a report, India ranked second in terms of being the most targeted country by religious hacktivist groups, after Israel.23 In April 2023, a well-coordinated DDoS attack was launched against major airports and healthcare institutions in India.24 Anonymous Sudan, which claimed responsibility for the incident, used a combination of Layer 3–4 and Layer-7 DDoS attacks that lasted nearly nine hours.25 While the consequences of DDoS attacks may appear insignificant, they should not be underestimated. These attacks can potentially incur significant costs to an organisation regarding time, finances, and reputation. Furthermore, they can lead to the loss or deterioration of essential services, including critical sectors such as healthcare. A threat actor might also employ a DDoS attack as a means to redirect focus from more sinister activities, such as the insertion of malware or the unauthorised extraction of data. As the government continues to spread awareness about such threats, organisations, especially those managing critical infrastructure, must take initiatives to prevent and mitigate DDoS attacks. Such organisations must develop a DDoS response plan and promote a culture of cyber hygiene among their workforce. In short, DDoS is no longer a low intensity/low impact threat but a danger with actual loss and cost. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Strategic Technologies | Cyber Security, Cyberspace | system/files/thumb_image/2015/ddos-attack-t.jpg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S-70 Okhotnik UCAV Debuts on the Russia–Ukraine Battlefield | July 31, 2023 | Akshat Upadhyay |

The Russian S-70 Okhotnik (Hunter) unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAV) was reportedly used on the Ukrainian battlefield on 27 June 2023, where it struck Ukrainian military facilities in the regions of Sumy and Kremenchuk.1 This is an important development in the war since it showcases Russian capability to move beyond tactical and ad-hoc equipped drones like Orlan-10, Lastochka, Forpost-R and Orion,2 commercial Chinese quadcopters (DJI and Air series)3 and the Shahed and Mohajer series loitering munitions (LMs) imported from Iran,4 to staking a major technological claim in the form of a UCAV. In the short term, Russia will still depend on Iranian expertise in LMs given that a manufacturing plant has been set up inside Russia.5 The successful strikes by the S-70, with the option of manned–unmanned teaming (MUM-T) with the Su-57 fighter jet, provide the country with a deployable option, still under development by other powers like the US and the UK. The Okhotnik project has been in the making since 20116 and has been envisaged as a “loyal wingman” for the Su-57.7 A loyal wingman is a UCAV which, using onboard AI, can collaborate with manned fighters and is seen as being significantly low-cost than its manned counterpart.8 This expands the tasking and deployment options for the pair (at the very least one UCAV and one manned fighter are being considered but the numbers of UCAV can increase depending on the cognitive load on the pilot). The project is being jointly developed by Sukhoi and Mikoyan as a sixth-generation heavy UCAV.9 A sixth generation air vehicle has parameters like onboard data fusion and artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities, advanced stealth airframes, advanced variable cycle engines and integration of directed energy weapons (DEW).10 Two prototypes have been developed so far, the first one with a circular exhaust and the latter with a more square-shaped one to increase stealth.11 Two more are under development and these are supposedly similar to the ones which will finally undergo serial production.12 The design of the S-70 is that of a ‘flying wing’, similar to that of the F-117 Nighthawk, the RQ-170 and the Shahed-136.13 Okhotnik’s first autonomous flight testing, which included a flight time of around 30 minutes, alongside an Su-57, was conducted on 27 September 2019.14 The Su-57 has been used as a flying laboratory for testing the Hunter’s avionics. Unguided bombs were tested in 2021,15 followed by the test-firing of Kh59 Mk2 precision guided munition (PGM) in May 2022.16 The current version of Su-57 is a single-seat fighter but a twin-seater variant has been flight-tested with the Hunter where the co-pilot will be exclusively responsible for controlling and monitoring the UCAV, with the pilot performing his/her basic functions. Certain other developments in this project merit attention. When operationally ready, each Su-57 will command up to four S-70s.17 Already, four Su-57s have been used to conduct suppression of enemy air defences (SEAD) in Ukraine on 9 June 2022.18 The interesting part was that all four were “linked to a single information network to destroy air defense systems through automatic communication systems, data transmission, navigation and identification in real-time”.19 The Okhotnik has also been trialed with the Mig-29.20 In a standalone mode, it may also be deployed on the still-in-development Project 23900 Ivan Rogonov helicopter carriers, each of which has a capacity to accommodate 4 S-70s.21 Russian analysts have also dubbed the S-70 the world’s first “outer space” drone.22 Manned–Unmanned Teaming (MUM-T)The Okhotnik’s strikes in Ukraine can act as proof of concept for the MUM-T concept, under development in a number of countries including India. MUM-T has been defined differently by different armed forces across the world. While the US Army Aviation Centre (USAACE) defines MUM-T as “synchronized employment of soldier, manned and unmanned air and ground vehicles, robotics, and sensors to achieve enhanced situational understanding, greater lethality, and improved survivability”,23 the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO)’s standardisation agreement (STANAG) calibrates five levels of interoperability (LOI) between manned and unmanned platforms,24 with the first being indirect receipt of UAV-related data, going up to level five which relates to the control and monitoring of the UAV along with launch and recovery functions.25 In India, the Combat Air Teaming System (CATS) is meant as an umbrella term for a combination of manned and unmanned assets which can reduce human casualties, perform air-to-air and air-to-ground strikes from a standoff distance and also act as atmospheric satellites for high altitude surveillance.26 The initial prototypes are being tested on the Jaguar aircraft and will later be fitted on the Tejas light combat aircraft (LCA) acting as the “mothership”.27 Similar projects are being developed in the US (collaborative combat aircraft or CCA)28 , Australia (air teaming system or ATS)29 and the UK (Project Tempest).30 Within the US, a number of parallel programs are in progress. The Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) is field testing the Skyborg program with the Kratos’ X-58 Valkyrie.31 The Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is moving ahead with the air combat evolution (ACE) program,32 and in a simulation featuring a US Air Force (USAF) pilot competing with an AI pilot under the AlphaDogFight program, had shown that AI could beat human pilots in number of fighter manoeuvres and targeting actions.33 There were obviously some caveats and one could say that the dice was loaded in favour of the AI. However, even granting those advantages to the AI, the performance has been nothing short of impressive and heralds the future of air combat. MUM-T, when implemented during conventional combat scenarios, offers the advantage of combining the strengths of manned and unmanned aircrafts, while complementing each other’s shortfalls. The UCAV can be sent ahead in a dense air defence (AD) environment to scout for targets, perform SEAD and force the adversary to reveal its surface to air missile (SAM) sites. This data, most of which is computed within the UCAV using edge processing, can be sent back to the manned fighter, already at standoff range, and used for conducting air and ground attacks. The UCAV, when equipped with either air-to-air or air-to-ground (AAM/AGM) missiles can also act as a ‘flying magazine’ for the manned fighter, increasing the inventory and range of the aircraft. With the number of unmanned platforms under the pilot’s control increasing and the unmanned platforms themselves carrying LMs, similar to what is envisaged in the CATS program, the pilot now has the opportunity to conduct what this writer calls “simultaneous multi-roles” (SMRs) where the capabilities of the manned fighter will increase manifold. At the same instant, the pilot can engage air targets, perform precision bombing against pin-point high value targets and saturate the battlefield with LMs and conventional unguided bombs. Air combat is likely to undergo a major change with the entry of UAVs of all shapes and sizes. Countries which can proactively take advantage of this phase of air combat evolution are likely to have a greater edge over their adversaries. As the Okhotnik trials and later operational use shows, the combination of the human mind and computational strength of microchips, integrated into a single system, has the potential to impose on the adversary a major decision dilemma regarding the system to be countered and can act as a combined arms offensive in the air. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Strategic Technologies | Russia-Ukraine Relations, Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) | system/files/thumb_image/2015/russia-ukrian-war-t.jpg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| South Africa’s Rhetoric of Non-alignment in Focus | July 31, 2023 | Abhishek Mishra |

Following months of speculations, a decision has finally been made—Russian President Vladimir Putin won’t attend the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) Summit which is taking place in Johannesburg from 22 to 24 August 2023. The development comes as a relief for South African officials as it helps Pretoria dodge an awkward diplomatic and legal dilemma. Being a signatory to the Rome Statute which governs the International Criminal Court (ICC), South African officials would have been obliged to arrest Putin upon arrival. In March 2023, ICC issued a warrant for Putin’s arrest over alleged war crimes committed in Ukraine.1 Two other members of BRICS—India and China—are not signatories to the Rome Statute. Brazil is a member but since it wasn’t hosting the meeting, it did not have to deal with this situation. The moment speculations about Putin’s possible attendance began, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa employed every possible means to diffuse the situation and navigate his way out of the tight diplomatic spot. First, his administration proposed Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov lead the Russian delegation instead of Putin. This request was denied by Moscow. Secondly, rumors began to fuel speculations that the BRICS summit could become a virtual summit or may even get shifted to China.2 Such rumors were categorically denied by Ramaphosa as his administration insisted on hosting a physical summit. Moreover, President Ramaphosa is trying to consolidate his own domestic standing and garner support from various flanks of his ruling party, the African National Congress (ANC), with the South African general elections scheduled to take place in 2024. US Ambassador’s AllegationThe troubled period for South African administration began on 11 May when the United States Ambassador to South Africa Reuben Brigety held a press conference in which he accused South African officials of allegedly loading weapons onto a sanctioned Russian ship in December 2022.3 This triggered a long drawn diplomatic spat between Washington and Pretoria. It was claimed that the Russian cargo ship known as The Lady R docked at Simon’s Town naval base near Cape Town last December with its tracking device switched off. This prompted questions whether the ship was loaded with arms before returning to Russia. Even before this development, tensions between US and South Africa were already palpable. On the anniversary of the invasion of Ukraine in February 2023, South African military participated in a ten-day exercise – Exercise Mosi, along with Russia and China. This provoked criticism both at home and abroad.4 With Ambassador Brigety’s accusation, South Africa’s officially proclaimed “non-aligned” position on the Russian invasion of Ukraine came under scrutiny. Following the press conference, the immediate fallout was felt in the financial markets with the South African Rand plummeting to a record low of 19.51 to the dollar.5 The other implication was the possibility of South Africa being suspended from the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which is due to expire in 2023. Under AGOA, South Africa currently enjoys preferential duty-free market access to the US, South Africa’s third-largest trading partner. If South Africa’s preferential status indeed gets suspended, then industries like wine, citrus and motor would be gravely affected, leading to job losses and reduced export revenues.6 In response, the South African government categorically denied US accusations and defended its decision to participate in military exercise with Russia and China citing its right to pursue its own international policy since it is a sovereign nation. South Africa’s Minister of Defence Thandi Modise claimed that the Lady R docked to deliver a shipment of ammunition for the South African National Defence Force’s Special Forces Regiment, equipment that had been ordered prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.7 Owing to the seriousness of the allegations and its potential impact on South Africa’s international image, Ramaphosa established a three-person panel to investigate the incident.8 However, the timeline for completing the investigation and providing a final report remains undetermined for the time being. South Africa’s Rhetoric of Non-AlignmentThe paradox of being formally neutral on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, yet parallelly deepening military relationship with Russia is continuing to strain US–South Africa relations. Right from the start, South Africa has insisted that it supports the “peaceful resolution” of the conflict.9 Pretoria along with a group of five African countries volunteered to visit both Moscow and Kyiv and constitute a “peace mission”. The delegation put forward a 10-point plan that stressed on unimpeded grain exports through the Black Sea. Yet in practical terms, Africa’s peace mission failed to yield meaningful results.10 The delegation faced several logistical and security challenges. Problems with the US have been further complicated with South Africa continuing to abstain on voting at the UN General Assembly resolutions calling for an end to the war and Russia’s withdrawal from Ukrainian territory. India has followed a similar path whereas China has voted against such resolutions. Although there are no cultural or linguistic ties between South Africa and Russia, the former’s support for the latter could be attributed to the roots of the ANC. Being Africa’s oldest liberation movement fighting against white minority rule in South Africa, the ANC relied heavily on support from the erstwhile Soviet Union. The armed wing of the ANC—known as Umkhonto we Sizwe—received arms, ammunitions, and military training from the Soviets in 1960s. With such historical affinities, it is understandable why South Africa would be standing on the fence on the Russia–Ukraine conflict. However, the question of whether South Africa has been able to substantiate its doctrine of non-alignment or usage of the term non-aligned is debatable.11 Additionally, the West had raised the stakes for South Africa to pursue a course of action tantamount to economic sabotage. Apart from potential suspension from AGOA, Putin’s arrival and South Africa’s failure to arrest him would have subjected Pretoria to penalties such as exclusion from various Western payments platform and protocols. On 9 June 2023, US Congressional leaders also issued a bipartisan letter urging President Joe Biden to question South Africa’s eligibility for continued inclusion in the AGOA and to consider moving the venue of 2023 AGOA Forum from South Africa to another country.12 Apart from these challenges, the principal line of argument coming from South African officials relates to its own role in negotiation and mediation on peace and security issues. Currently, there are not many states that have access to both President Putin and President Volodymyr Zelensky and can engage with the two parties simultaneously. This sentiment has been echoed by South Africa’s Minister for International Relations and Cooperation Dr Grace Naledi Pandor. However, by being a signatory to the Rome Statute, South Africa has inadvertently put itself in a difficult position when it comes to hosting leaders in the future. Unless the Rome Statute of 2002 is amended, the question of any future state visit by the President of Russia to South Africa will remain in question. With South Africa slated to host the G20 Summit in 2025, similar kind of diplomatic pressure may continue to be applied unless the statue is amended. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Eurasia & West Asia | South Africa, Russia, Non-alignment | system/files/thumb_image/2015/south-africa-russia-t.jpg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| US Voluntary Code of Conduct on AI and Implications for Military Use | July 28, 2023 | Akshat Upadhyay |

Seven technology companies including Microsoft, OpenAI, Anthropic and Meta, with major artificial intelligence (AI) products made voluntary commitments regarding the regulation of AI at an event held in the White House on 21 July 2023.1 These eight commitments are based on three guiding principles of safety, security and trust. Areas and domains which are presumably impacted by AI have been covered by the code of conduct. While these are non-binding, unenforceable and voluntary, they may form the basis for a future Executive Order on AI, which will become critical given the increasing military use of AI. The voluntary AI commitments are the following:

The eight commitments of US’s Big Tech companies come a few days after the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) for the first time convened a session on the threat posed by AI to global peace and security.3 The UN Secretary General (UNSG) proposed the setting up of a global AI watchdog comprising experts in the field who would share their expertise with governments and administrative agencies. The UNSG also added that UN must come up with a legally binding agreement by 2026 banning the use of AI in automated weapons of war.4 The discussion at the UNSC can be seen as elevating the focus from shorter term AI threat of disinformation and propaganda in a bilateral context between governments and Big Tech companies to a larger, global focus on advancements in AI and the need to follow certain common standards, which are transparent, respect privacy of individuals whose data is ‘scraped’ on a massive scale, and ensure robust cybersecurity. Threat posed by AILawmakers in the US have been attempting to rein in the exponential developments in the AI field for some time now, since not much is known about the real impact of the technology on a longer-term basis. The reactions to the so-called danger of AI have been polarizing, with some even equating AI with the atom bomb and terming the current phase of growth in AI as the ‘Oppenheimer moment’5 , after the scientist-philosopher J. Robert Oppenheimer, under whom the Manhattan Project was brought to a fruitful conclusion with the testing of the first atomic bomb. This was the moment that signaled the start of the first nuclear age—an era of living under the nuclear shadow that persists to this day. The Oppenheimer moment, therefore, is a dividing line between the conventional past and the new present and presumably the unknown future. Some academics, activists and even members of the Big Tech community, referred to as ‘AI doomers’ have coined a term, P(doom), in an attempt to quantify the risk of a doomsday scenario where a ‘runaway superintelligence’ causes severe harm to humanity or leads to human extinction.6 Others refer to variations of the ‘Paperclip Maximiser’, where the AI is given a particular task to optimise by the humans, understands it in the form of maximising the number of paperclips in the universe and proceeds to expend all resources of the planet in order to manufacture only paperclips.7 This thought experiment was used to signify the dangers of two issues with AI: the ‘orthogonality thesis’, which refers to a highly intelligent AI that could interpret human goals in its own way and proceed to accomplish tasks which have no value to the humans; and ‘instrumental convergence’ which implies AI taking control of all matter and energy on the planet in addition to ensuring that no one can shut it down or alter its goals.8 Apart from these alleged existential dangers, the new wave of generative AI9 , which has the potential of lowering and in certain cases, decimating entry barriers to content creation in text, image, audio and video format, can adversely affect societies in the short to medium term. Generative AI has the potential to birth the era of the ‘superhuman’, the lone wolf who can target state institutions through the click of his keyboard at will.10 The use of generative AI in the hands of motivated individuals, non-state and state actors, has the potential to generate disinformation at scale. Most inimical actors and institutions have so far struggled to achieve this due to the difficulties of homing onto specific faultlines within countries, using local dialects and generating adequately realistic videos, among others. This is now available at a price—disinformation as a service (DaaS)—at the fingertips of an individual, making the creation and dissemination of disinformation at scale, very easy. This is why the voluntary commitments by the US Big Tech companies are just the beginning of a regulatory process that needs to be made enforceable, in line with legally binding safeguards agreed to by UN members for respective countries. Military Uses of AISlowly and steadily, the use of AI in military has been gaining ground. The Russia-Ukraine war has seen deployment of increasingly efficient AI systems on both sides. Palantir, a company which specialises in AI-based data fusion and surveillance services,11 has created a new product called the Palantir AI Platform (AIP). This uses large language models (LLMs) and algorithms to designate, analyse and serve up suggestions for neutralising adversary targets, in a chatbot mode.12 Though Palantir’s website clarifies that the system will only be deployed across classified systems and use both classified and unclassified data to create operating pictures, there is no further information on the subject available in the open domain.13 The company has also assured on its site that it will use “industry-leading guardrails” to safeguard against unauthorized actions.14 The absence of Palantir from the White House declaration is significant since it is one of the very few companies whose products are designed for significant military use. Richard Moore, the head of United Kingdom’s (UK) MI6, on 19 July 2023 stated that his staff was using AI and big data analysis to identify and disrupt the flow of weapons to Russia.15 Russia is testing its unmanned ground vehicle (UGV) Marker with an inbuilt AI which will seek out Leopard and Abrams tanks on the battlefield and target them. However, despite being tested in a number of terrains such as forests, the Marker hasn’t been rolled out for combat action in ongoing conflict against Ukraine.16 Ukraine has fitted its drones with rudimentary AI that can perform the most basic edge processing to identify platforms like tanks and pass on only the relevant information (coordinates and nature of platform) amounting to kilobytes of data to a vast shooter network.17 There are obviously challenges in misidentifying objects and the task becomes exceedingly difficult when identifying and singling out individuals from the opposing side. Facial recognition softwares have been used by the Ukrainians to identify the bodies of Russian soldiers killed in action for propaganda uses.18 It is not a far shot to imagine the same being used for targeted killings using drones. The challenge here of course is systemic bias and discrimination in the AI model which creeps in despite the best intentions of the data scientists, which may lead to inadvertent killing of civilians. Similarly, spoofing of the senior commanders’ voice and text messages may lead to passing of spurious and fatal orders for formations. On the other hand, the UK-led Future Combat Air System (FCAS) Tempest envisages a wholly autonomous fighter with AI integrated both during the design and development phase (D&D) as well as the identification and targeting phase during operations.19 The human, at best, will be on the loop. ConclusionThe military use of AI is an offshoot of the developments ripping through the Silicon Valley. As a result, the suggestions being offered to rein in the advancements in AI need to move beyond self-censorship and into the domain of regulation. This will be needed to ensure that the unwarranted effects of these technologies do not spill over into the modern battlefield, already saturated with lethal and precision-based weapons. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Strategic Technologies | Artificial Intelligence, Military Modernisation | system/files/thumb_image/2015/artificial-intelligence-t.jpg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| India's Arctic Endeavours: Capacity Building and Capability Enhancement | July 27, 2023 | Anurag Bisen |

SummaryWhile India has made progress on polar research, it lags behind other Asian countries in terms of infrastructure, research capabilities, and international collaborations in the Arctic. India needs to strengthen domestic capacity and capabilities to effectively engage with the evolving dynamics of the Arctic and contribute to scientific advancements, economic opportunities, and regional strategic engagements. IntroductionCapacity building and capability enhancement remain central to India’s Arctic endeavours. While ‘capacity’ refers to material adequacy, ‘capability’ refers to the possession of domain-specific qualifications, expertise, and skills. While capacity can be built rapidly, capability is realised incrementally over a period of time through the intellectual and educational processes of training, learning, operational experience, and equipment exploitation. An important consideration as regards national capacity and capability is that in the former case, the timelines can be shortened through acquisition, such as by buying an ice-class research vessel off-the-shelf or by renting such a vessel. However, capability – particularly in critical and niche domains, is acquired by nations over time. India’s Arctic Policy 2022The relevance of the Arctic for India can be broadly explained under three categories: Scientific Research, Climate Change and Environment; Economic and Human Resources; and Geopolitical and Strategic reasons.1 Geopolitically, the Arctic is significant for India because it is an arena of strategic contestation for two of its most important strategic partners, the US and Russia and its principal adversary, China. The sheer range of the issues that impact the Arctic – from climate change, connectivity, resource development, and big power confrontation, have significance for the whole world, including India. India’s Arctic Policy (hereinafter Policy), issued in 2022, is cognisant of our inadequacies in the Arctic and has, hence, rightfully designated National Capacity-Building as its sixth pillar. The other five pillars also include aspects related to capability enhancement and capacity building. The Policy aims to enhance India’s capacities in the Arctic through the development of a robust human, institutional, and financial base.2 This is sought to be achieved by strengthening the National Centre for Polar and Oceanographic Research (NCPOR) and other relevant academic and scientific institutions in the country, identifying nodal institutes, and promoting partnerships among institutions and agencies. The policy also intends to promote research capacities in Indian universities in Arctic-related fields; broaden the pool of experts in Arctic-related sectors such as mineral, oil, and gas exploration, blue-bio economy, and tourism; strengthen training institutions for training seafarers in polar/ice navigation and develop region-specific hydrographic capacity and skills required to undertake Arctic transits; develop indigenous capacity for building ice-class ships; expand India's trained manpower in maritime sectors; and build broad institutional capacity for the study of Arctic-related maritime, legal, environmental, social, policy, and governance issues. India’s Arctic Policy also hopes to promote a larger pool of experts in the government as well as academia and also create capacities for research in the country on Arctic governance and geopolitics.3 Mapping India’s Current Arctic EngagementsIndia, China, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore are the five Asian countries who joined the Arctic Council as Observers in 2013. A comparative analysis of India, China, Japan, and South Korea's capacity building activities can help in understanding why capacity building is crucial.

Table 1: Arctic Capacity Building Activities Comparison

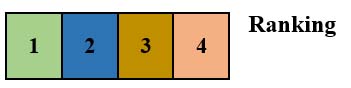

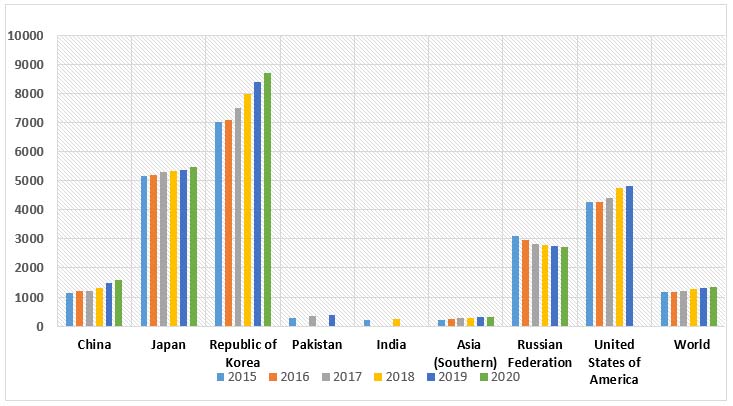

As can be seen from the above table, India has the leading rank only on two occasions. In 1920, India, as a dominion of the British, along with Japan, was one of the original 14 High Contracting Parties to sign the Svalbard Treaty. Thereafter, in 2013, we became Observers together with the other four Asian states. To be sure, India has made tremendous strides in polar research, being one of two developing nations to have a research station in the Arctic. India has lagged behind the other three Asian Arctic Observer countries, however, as regards the first expedition to the Arctic or setting up of a research station or the release of an Arctic Policy. Table 2 compares India’s participation in Arctic Council Task Forces with the other Asian Observer states, except Singapore. Japan figures in the highest at six, China and South Korea are at five each, while India has participated in three Task Forces. Table 2: Participation in Arctic Council Task Forces

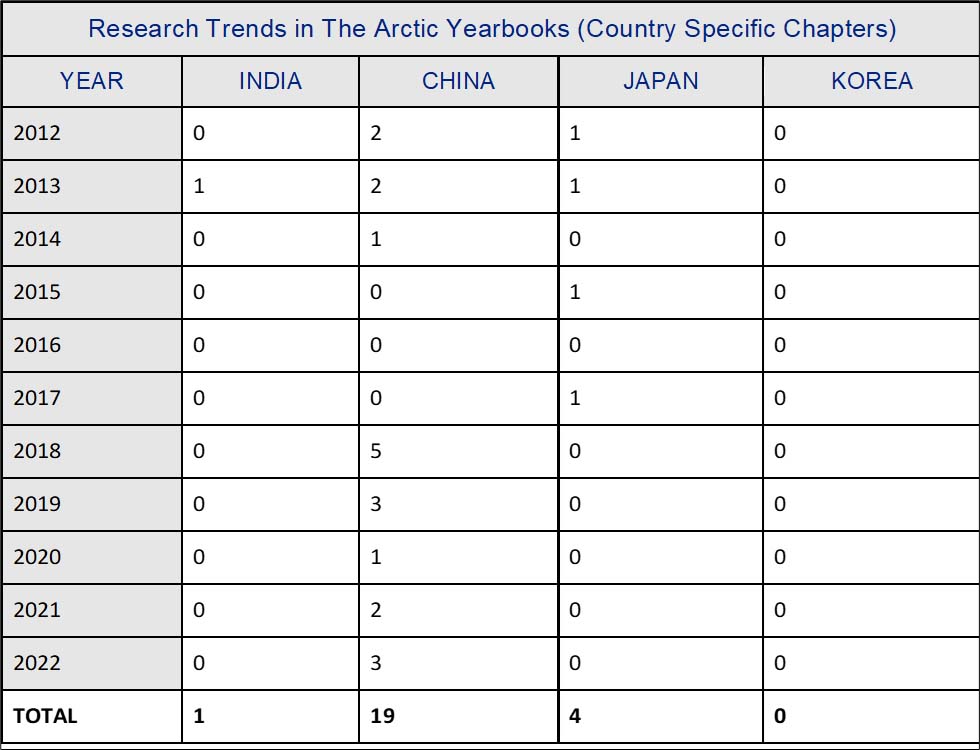

Source: Author’s tabulations from The Arctic Council Table 3 compares country-specific chapters in the Arctic Yearbook for a 10-year period from 2012. China tops the list with 19 mentions, Japan is placed second with four mentions, while India is placed third with one mention. This reflects the inadequacy of Arctic-related research, economic and political activity being undertaken in India and indicates the lack of capacity and capability on the Arctic in the country. Table 4: Key International Collaborations

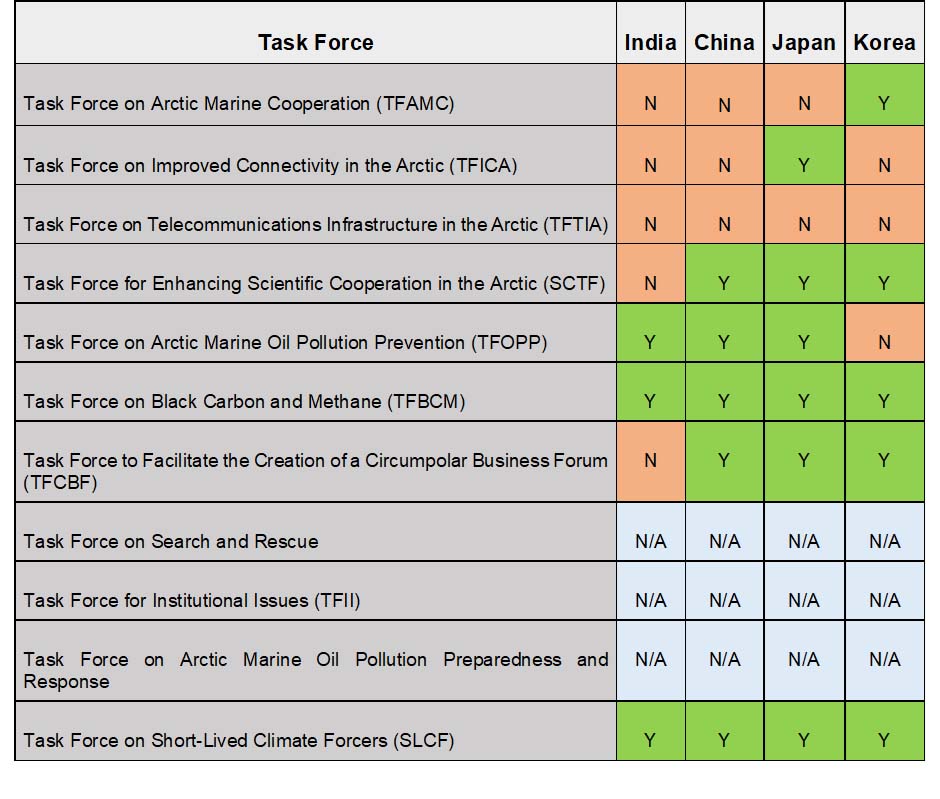

Source: Author’s Tabulation Based on Open Source Information. Table 4 shows the key international Arctic-related collaborations and activities of India, Japan, China and South Korea. While India has a bilateral dialogue with Russia on the Arctic, the MoU with Polar Knowledge with Canada was signed in 2020. There are also engagements with institutions in Norway and Japan, albeit on a smaller scale. In comparison, however, international collaborations and Arctic-related activities of China, Japan and South Korea are far more developed. For instance, the three countries have a trilateral dialogue. China also has bilateral dialogues on the Arctic with Russia, US, Norway, Denmark, UK, and France. Additionally, there is a China-Nordic Research Centre (CNARC) which is an international consortium initiated by the Polar Research Institute of China (PRIC) in collaboration with respective institutes in the Nordic countries to promote and facilitate China-Nordic cooperation for Arctic research.14 China has also established an Arctic Science Observatory in Iceland, a joint project by Chinese and Icelandic research institutions to further the scientific understanding on Arctic phenomena.15 China’s first overseas land satellite receiving station – China Remote Sensing Satellite North Polar Ground Station (CNPGS), has also been established in Sweden.16 Table 5: Researchers per Million Inhabitants

Source: “Science, Technology and Innovation”, UNESCO Sustainable Development Goals. Table 5 shows comparative data of researchers per million inhabitants (RPMI) of India with China, Japan and South Korea, as well as US and Russia. The RPMI is UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Indicator 9.5.2 and is defined as the number of professionals engaged in the conception or creation of new knowledge (who conduct research and improve or develop concepts, theories, models, techniques instrumentation, software or operational methods) during a given year expressed as a proportion of a population of one million. In 2018, India had 252.7 RPMI, one fifth of the world average of 1265 RPMI. The corresponding figures for China, Russia, US, Japan and South Korea are 1307.1, 2784.3, 4748.8, 5331.1, and 7980.4 respectively. India and Polar ResearchPresently, India’s polar research for Antarctic, Arctic, Southern Ocean and Himalayas is budgeted under the umbrella of Polar Science and Cryosphere (PACER) programme of the Ministry of Earth Sciences (MoES).17 The total financial allocation (BE) under the PACER programme for 2018–19, 2019–20 and 2020–21 was Rs 365 crores.18 For 2022–23, the demand for grants under PACER is Rs 140 crores, while that for NCPOR is Rs 23.67 crores.19 This amounts to approximately US$ 17.5 million for the overall PACER programme and approximately US$ 3 million for the NCPOR for the year. Considering that India’s Antarctic Programme is about five times bigger20 than its Arctic programme, it is estimated that allocations for the Arctic are approximately Rs 10–15 crores per year or between US$ 1.5–2 million annually. It is noteworthy that the entire MoES budgeted expenditure for FY 2022–23 is Rs 2,653.51 crores (~US$ 350 mn). This includes the budgets for the Ministry Headquarter in New Delhi; the two attached offices—the Centre for Marine Living Resources and Ecology (CMLRE) and the National Center for Seismology (NCS); two subordinate offices—the India Meteorological Department (IMD) and the National Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting (NCMRWF); and five autonomous institutions—National Institute of Ocean Technology (NIOT), National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research (NCPOR), Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Service (INCOIS), Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM) and National Centre for Earth Science Studies (NCESS). This meagre budget of approximately US$ 350 million caters for provision of national services for weather, climate, ocean and coastal state, hydrology, seismology, and natural hazards. It also caters for exploring and harnessing of marine living and non-living resources in a sustainable manner and to explore the three poles of the Earth (Arctic, Antarctic and Himalayas). To contextualise the MoES’ Arctic budget, it is pertinent to highlight the South Korean example. The Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI) is the primary (government sponsored) research institute for the national polar programme in South Korea. KOPRI runs a research station in Svalbard and has a number of pan-Arctic observation sites. It is involved in around 20 Arctic (large and smaller) projects, sends around 200 expeditioners a year to the Arctic and has an investment of approximately US$ 13 million (in research grants). This is just one of the Korean institutions engaged in Arctic Research. The Korea Arctic Research Consortium is yet another new initiative (launched in 2015), with 30 partner institutions and a secretariat at KOPRI that aims to strengthen collaboration in Korean Arctic research and bring together science, industry and policy.21 A 2018 commentary in Nature claimed that China has earmarked US$ 3 billion for polar research over the next decade. China also raised its financial inputs in Antarctic research. From 2001 to 2016, China invested 310 million yuan (about US$ 45 million) in related projects, which is 18 times the total for the period 1985–2000. In terms of research capacities, against a world average of 1.9 per cent of GDP on research, India’s expenditure at under 0.7 per cent is less than half. The corresponding figures for China, Japan and S Korea are 2.4 per cent, 3.2 per cent, and 4.8 per cent respectively. There are 13 Chinese institutions affiliated to the University of the Arctic (UArctic) against three from India, of which two became members recently (in May 2023).22 Polar studies also remain largely absent from schoolbooks for secondary and senior secondary levels. About 25 Institutes and Universities are currently involved in Arctic research in India and about a hundred peer-reviewed papers have been published on Arctic issues since 2007.23 India’s academic capacity needs to be substantially augmented at all levels, from primary and secondary education to higher education and post-doctoral studies, in order to compete with China, Japan, and South Korea. On 28 June 2023, the Union Cabinet approved the introduction of the National Research Foundation (NRF) Bill 2023 in the Parliament that will seed, grow and promote Research and Development (R&D) and foster a culture of research and innovation throughout India’s universities, colleges, research institutions, and R&D laboratories. With an initial budget of Rs 50,000 crore over five years, the NRF aims to address the lack of funding for R&D in India.24 Modelled after the National Science Foundation (NSF) of the United States, the NRF will cover various fields, including natural sciences, engineering, social sciences, arts, and humanities, with a focus on finding solutions to societal challenges in India. The establishment of the NRF is seen as a major milestone for science in India, aiming to improve research capabilities, promote a research culture, and link research to society and industry. The setting up of NRF will address a long-standing policy gap and if managed well, has the potential to address the inadequacies in India’s scientific research sector. The NRF will be administratively housed in the Department of Science and Technology (DST) and will be overseen by a governing board and executive council with funding for research projects shared between the DST and industry. It will foster collaboration between academia, government, and research institutions. It is hoped that India’s Arctic research efforts will also get a boost and new horizons for Artic research will be opened Policy RecommendationsWhole-of-Nation ApproachIndia’s 2022 Arctic Policy was intended for a whole-of-government approach. It is crucial to adopt a whole-of-nation approach to build capacities and enhance capabilities, with active participation of industry, academia, and think tanks. Interdisciplinary ResearchIt is essential to adopt an interdisciplinary research approach in order to understand not only the climate change-induced changes in the Arctic environment, but also the geo-strategic contestation that are underway, which have many scientific and policy implications. To conceptualise and conduct policy-relevant research on the Polar Regions, a multidisciplinary group of specialists need to collaborate closely within a single academic unit to develop viable research projects and academic programmes. Domestic research capacities need to be promoted by expanding programmes in Arctic-related earth sciences and climate change in Indian universities. For this, Polar Research Chairs, faculty and facilities in select Indian universities would need to be established. Introduction of a Master of Science and PhD programmes in Polar Studies by institutions such as the NCPOR can further generate research capabilities. In addition, expanded cooperation with the various Arctic science and research institutes and Indian institutes such as the Himalayan Science Council and IITs can enhance capabilities. Knowledge and expertise on Arctic maritime legal issues, for instance, can help us examine issues like the implication of opening of Northern Sea Route in the context of China’s Malacca Dilemma. Expedite Acquisition of Polar Research VesselThe lack of a dedicated Polar Research Vessel (PRV) is a serious impediment in the growth of India’s polar activities. On 29 October 2014, the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs had approved the acquisition of a PRV at a cost of Rs 1,051.13 crore within 34 months. The vessel, however, is yet to be acquired. Enhance International Arctic CooperationChina, Japan and South Korea undertake trilateral cooperation on Arctic. India could discuss Arctic bilaterally with Russia and Japan and thereafter have separate discussions on the Arctic with the Nordics, as part of the India-Nordic Summit, not just at the Track 1 level but at Track 1.5 and Track 2 levels as well. As India completes 10 years as AC Observer, like its counterparts, India should consider hosting AC events to increase its engagement with the Council members. Rename MoES as Ministry of Ocean and Earth Sciences (MOES)This can generate greater public consciousness of the oceans, especially to mitigate some effects of sea-blindness in the land-centric bureaucracy. Although it could be argued that Earth Sciences includes Ocean sciences, the word Earth is largely identified with land rather than oceans which cover 70 per cent of the earth’s surface. It may be recalled that the erstwhile NCAOR was renamed as NCPOR, to convey a wider geographical coverage. Three of MoES’ autonomous institutions have the word Ocean in their names and it is only right that the ministry also reflects the primacy of Oceans in the work that it undertakes. The NCPOR obviously needs to be suitably strengthened and fresh recruitment of scientists exclusively for Arctic research needs to be undertaken. Establish a Think Tank for Earth Sciences, Oceanographic and Polar AffairsThe think tank, under the aegis of the MOES, could work on India-specific Arctic and Antarctic-related projects apart from the scientific field, polar and oceanographic affairs and earth sciences. Aspects related to geo-politics, governance, maritime law, connectivity, energy security and trade, among others can be given focussed attention. Include members from the Academia, Think Tanks and Industry in the EAPGThe execution and implementation of India’s Arctic Policy is being undertaken through an inter-ministerial Empowered Arctic Policy Group (EAPG).25 The EAPG ought to include members of the academia, think tanks and the industry to broad base Arctic-related endeavours in India. ConclusionIndia's engagement in the Arctic requires significant efforts to build capacity and enhance capabilities. While India has made progress in polar research, it lags behind other Asian countries in terms of infrastructure, research capabilities, and international collaborations in the Arctic. Limited budgetary allocations for Arctic research and low expenditure on R &D indicate the need for increased investment and resources. To address these gaps, India must prioritise the acquisition of necessary infrastructure, invest in R &D, and strengthen training institutions. This includes the acquisition of a dedicated PRV, promoting interdisciplinary research approaches, and expanding programmes in Arctic-related fields at Indian universities. Collaboration with Arctic science and research institutes, as well as international partnerships, should be fostered to enhance India's presence and contributions in the region. Furthermore, India needs to adopt a whole-of-nation approach – involving industry, academia, and think tanks, to build a comprehensive institutional base on Arctic issues. By strengthening domestic capacity and capabilities, India can effectively engage with the evolving dynamics of the Arctic and contribute to scientific advancements, economic opportunities, and strategic engagements in the region. Views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Manohar Parrikar IDSA or of the Government of India.

|

Non-Traditional Security | Arctic, India | system/files/thumb_image/2015/arctic-india-t.jpg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khalistan Movement: Recent Activities and Indian Response | July 26, 2023 | Abhishek Verma |