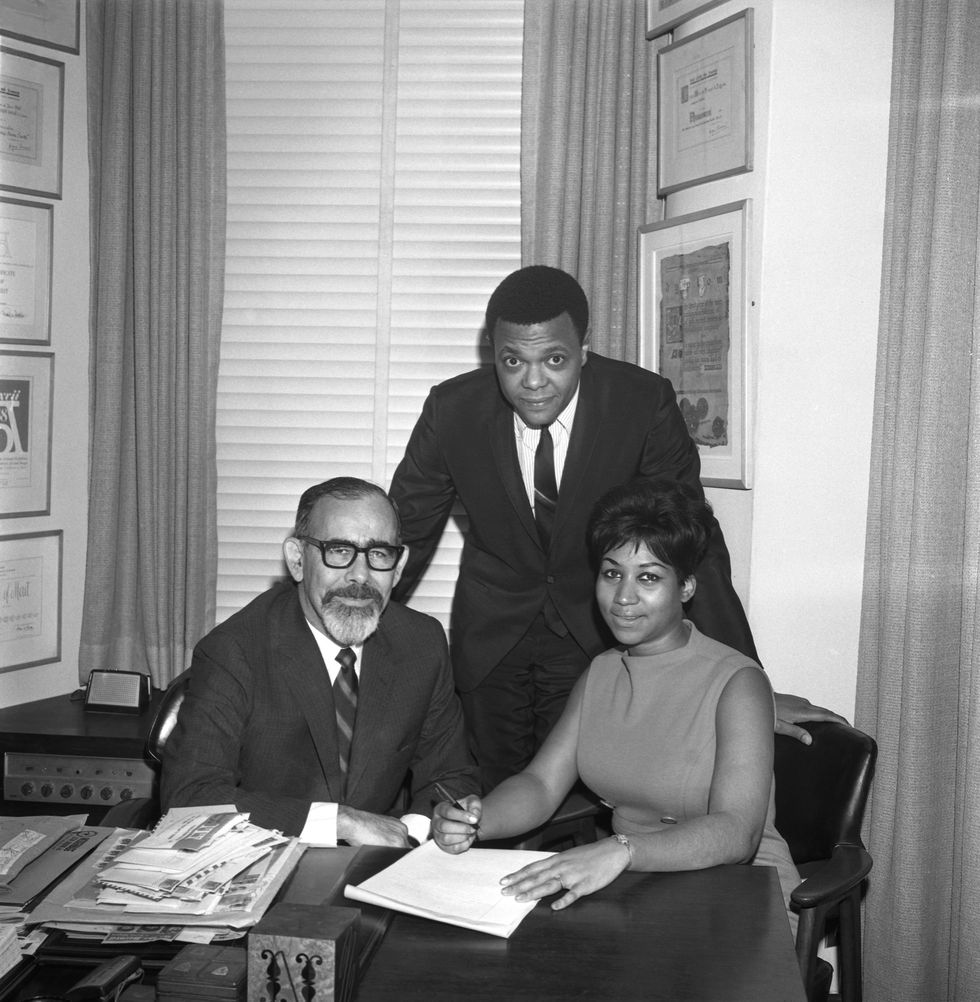

If there’s one thing that Aretha Franklin will always be remembered for, it’s how to spell out respect.

When the then-24-year-old released her rendition of “Respect” in April 1967, audiences immediately grasped onto the confidence and independent spirit that the song’s empowering sass elicited. Within weeks, it flew to No. 1 on the Billboard charts, where it reigned for 12 weeks, but more importantly, it quickly became a rallying cry that marginalized groups — especially the civil rights and women’s rights movements — adopted as an anthem since it preached the essential message that everyone’s voices deserved to be heard.

But the song didn’t start out that way. In fact, Franklin had nothing to do with the original 1965 release, which, ironically, is a relic of a misogynistic time.

Despite the tone of the first rendition, Franklin took the song and flipped it on its head, turning it into one of the most powerful songs of a generation.

The original song had 'masculine appeal'

Before his song “(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay,” which hit No. 1 posthumously in 1968, Otis Redding had released “Respect” in 1965.

While the general melody and lyrics were similar to Franklin’s take, the message of the original — which peaked at No. 4 on the charts — was the complete opposite. “It's an upbeat version of the traditional family values of the 1950s and 1960s: Man works all day, man comes home for dinner and demands respect from his wife,” CBS News described it in 2018, adding that it had a “masculine appeal from a working man to a housewife that feels a shade misogynistic through today's lens.”

Some of the pronouns were flipped, so that it fit that old school view of home life, with lyrics like: “Hey little girl, you're so sweet, little honey / And I'm about to, just give you all of my money / And all I'm asking, hey / A little respect when I come home.”

Early empowerment and activism gave Franklin the natural inclination to flip "Respect"

Long before she came across the Redding song, Franklin had already been grooming herself as an activist — by going on tour with Martin Luther King Jr.

“I don't think anyone knew how significant he would be in history, but everyone knew what he was trying to do and certainly trying to gain equal rights for African Americans and minorities,” Franklin told Ebony in 2013.

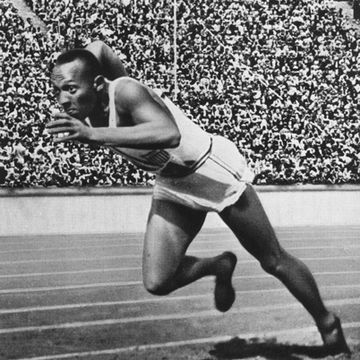

So she asked for her dad’s permission and set off on parts of King’s tour, along with Harry Belafonte and Jesse Jackson. “I always had a great admiration for [King] and his sense of decency and the justice that he wanted. He was a good man.”

Standing on the frontlines of the civil rights movement, Franklin was soon committed to also speaking out and breaking down barriers — and when she heard Redding’s take on “Respect,” she saw the skeleton of a power anthem.

“Aretha wrote most of her material or selected the songs herself, working out the arrangements at home and using her piano to provide the texture,” her producer Jerry Wexler told Rolling Stone. “In this case, she just had the idea that she wanted to embellish Otis Redding’s song. When she walked into the studio, it was already worked out in her head.”

So Franklin arrived at the New York City recording studio on February 14, 1967, with a mission — and a clear vision. She wanted to hang onto the original tempo and the bulk of the lyrics but add a bridge and call-and-response section, with her sisters Carolyn and Erma singing backup, according to the Los Angeles Times.

READ MORE: 5 Fascinating Facts About Aretha Franklin

The line 'sock it to me’ came to the sisters while looking out on the streets of Detroit

Among the changes the sisters made were spelling out the word respect — literally — as well as coming up with the iconic “sock it to me” phrase on repeat, which came about rather organically.

“Well, I heard Mr. Redding's version of it. I just loved it — and I decided that I wanted to record it,” Franklin said on NPR’s Fresh Air. “My sister Carolyn and I got together. I was living in a small apartment on the West Side of Detroit. And [with the] piano by the window, watching the cars go by, and we came up with that infamous line, the ‘sock It to me’ line.”

She said that at the time, it was a popular “cliché of the day.” “Some of the girls were saying that to the fellows, like, sock it to me in this way or sock it to me in that way,” Franklin continued. “Nothing sexual, and it's not sexual. It was non-sexual, just a cliché line...It just kind of perpetuated itself and went on from there.”

Even those in the studio on recording day were taken by the new rendition, with one of the engineers Tom Dowd literally floored by the “sock it to me” chant: “I fell off my chair when I heard that!”

Additionally, the back-and-forth of the women’s voices added to the powerful message of unity. “I have been in many studios in my life, but there was never a day like that,” fellow engineer Arif Mardin told Rolling Stone. “It was like a festival. Everything worked just right.”

"Respect" instantly became an anthem

Before the song was released, Redding went up to Wexler’s office and he played it for the artists. “He said, ‘She done took my song,’” Wexler told Rolling Stone. “He said it benignly and ruefully. He knew the identity of the song was slipping away from him to her.”

And that’s exactly what happened. “‘Respect' suddenly became an anthem of women's empowerment,” CBS News described. “The interplay between Franklin and her backup singers became the voice of female solidarity. The confidence of Franklin's vocals became a musical force behind the women's movement. It was a powerful assertion that women — and in particular, women of color — deserved respect. It became a female rallying cry.”

The women’s rights movement wasn’t the only one drawn to the message — it also unified both sounds of the color lines in an age of the civil rights movement. “In Black neighborhoods and white universities, her hits came like cannonballs, blowing holes in the stylized bouffant and chiffon Motown sound, a strong new voice with a range that hit the heavens and a center of gravity that was very close to Earth,” author Gerri Hirshey of Nowhere to Run: The Story of Soul Music wrote.

That powerful message that related to both communities came about by her ability to infuse a universality along with passion into the lyrics, as author David Ritz of Respect: The Life of Aretha Franklin told The Washington Post: “She deconstructed and reconstructed the song. She gave it another groove the original song did not have...It took on a universality the original never had. I think it is a credit to her genius [that] she was able to do so much with it… Her version is so deep and so filled with angst, determination, tenacity and all these contradictory emotions. That is how it became anthemic.”

READ MORE: Aretha Franklin and 11 Other Black Singers Who Got Their Start in Church

The song’s legacy lives on

Though Franklin passed away in 2018 due to complications from pancreatic cancer, the relevance of her song lives on. It’s cemented its place in pop culture, appearing in wide-ranging films like Mystic Pizza, Forrest Gump and Bridget Jones’s Diary and has been covered by diverse artists like Reba McEntire, Janice Joplin, Ike and Tina Turner, Kelly Clarkson, and Justin Bieber.

Franklin herself told NPR that the song definitely went on to hold more meaning than she originally expected. “In later times, it was picked up as a battle cry by the civil rights movement. But when I recorded it, it was pretty much a male-female kind of thing. And more in a general sense, from person-to-person — I'm going to give you respect and I'd like to have that respect back or I expect respect to be given back.”

But in the ultimate show of respect, Franklin added that her personal success with her music doesn’t matter as much as her paving the way for the next generation to pick up where she left off. “I’m very appreciative of all of the awards I’ve been given,” she told Ebony. “People don’t have to give you anything, so I absolutely appreciate that. Hopefully I have presented myself on a level that any young lady would be delighted to follow.”