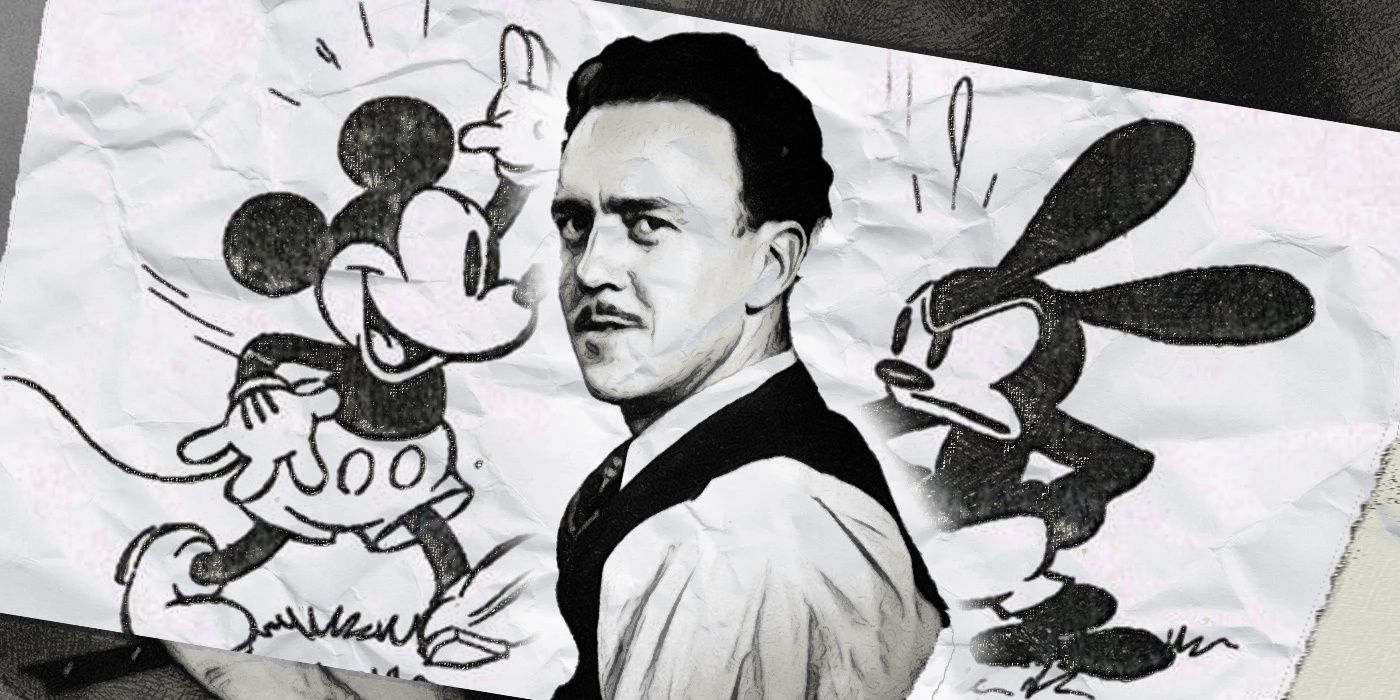

Go back to the earliest Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphony cartoons, and you’ll see his name prominently featured. For decades, Disney films credited him for “special processes,” and he helped advise Alfred Hitchcock’s effects crew on The Birds. Chester J. Lampwick of The Simpsons was inspired by him, or at least a popular misconception of him and his relationship with Walt Disney. But just who was Ub Iwerks, and how were he and Walt really connected?

The first question is easy to answer. Ub Iwerks (born Ubbe Ert Iwwerks) was a cartoonist, animator, and special effects man, born and raised in Kansas City. Originally a commercial artist, he was lured into animation by Walt, and throughout the 1920s he was the among the top animators at the Disney Brothers Studio (later Walt Disney Productions) – at times, the only skilled animator on staff. Iwerks set out on his own in the early 30s, but except for Flip the Frog, none of his characters became even a minor cartoon star. By the time he returned to the Disney fold, Iwerks was through with animation. He moved into visual effects and special photographic processes, and it was that work he diligently pursued until his death in 1971.

Iwerks’ relationship to Walt, and his contributions to the Disney legacy, make for a longer and more complex story. When they first met, it was as co-workers, two 18-year-old kids hired by the Pesmen-Rubin Commercial Art Company as apprentice artists and destined for layoffs after brief service with the firm. Of any two artists there, they were an unlikely duo. Walt, even then, was eager, optimistic, and ambitious, in a hurry to learn and improve. Those who knew Iwerks described him as shy, monosyllabic and, unusually for a cartoonist, humorless. But the two men became friends. Not long after their layoff, they also became business partners.

Iwerks-Disney (so named because the reverse sounded too much like an optical firm) was a commercial art firm not unlike the one the young partners had just left. Walt was the cartoonist and the go-getting salesman (and the source of start-up capital, though it took haggling with his parents to get the $250 from his savings), while Iwerks did lettering and any straight drawing. They cleared $135 in their first month, more than Pesmen-Rubin paid them, but when Iwerks spotted a listing for a cartoonist job at the Kansas City Slide Company, he persuaded Walt to put in for it and leave their firm to him. But when Walt got the job, Iwerks soon proved himself inept at salesmanship, or any aspect of an art business besides the drawing itself. Iwerks-Disney folded, and Iwerks himself joined Walt at Kansas City Slide.

Working there, the boys were introduced to animation. The primitive cut-outs used for Kansas City Slide’s theater ads were a long way away from the cartoon shorts coming out of New York, but they became a passion with Walt. He ingratiated himself to the technicians at every stage of the process, studied and experimented on his own time, and started hustling his own work done at night after a full day preparing ads. Iwerks seems to have kept to his drawing desk until Walt decided to strike out on his own again and persuaded his friend to come with him. It wouldn’t be a partnership this time; Iwerks was one of six animators employed at Laugh-O-Gram Films. They were all young, boisterous, and swept up in the possibilities of their fledgling medium.

What they weren’t was first-class animators. Surviving Laugh-O-Gram shorts betray their nature as the work of pals just out of boyhood learning a craft. The distribution arrangement for their work was unfavorable and the distributor went bankrupt. Laugh-O-Gram followed suit not long after, shuttering in 1923. Iwerks retreated to Kansas City Slide before then, while Walt headed west.

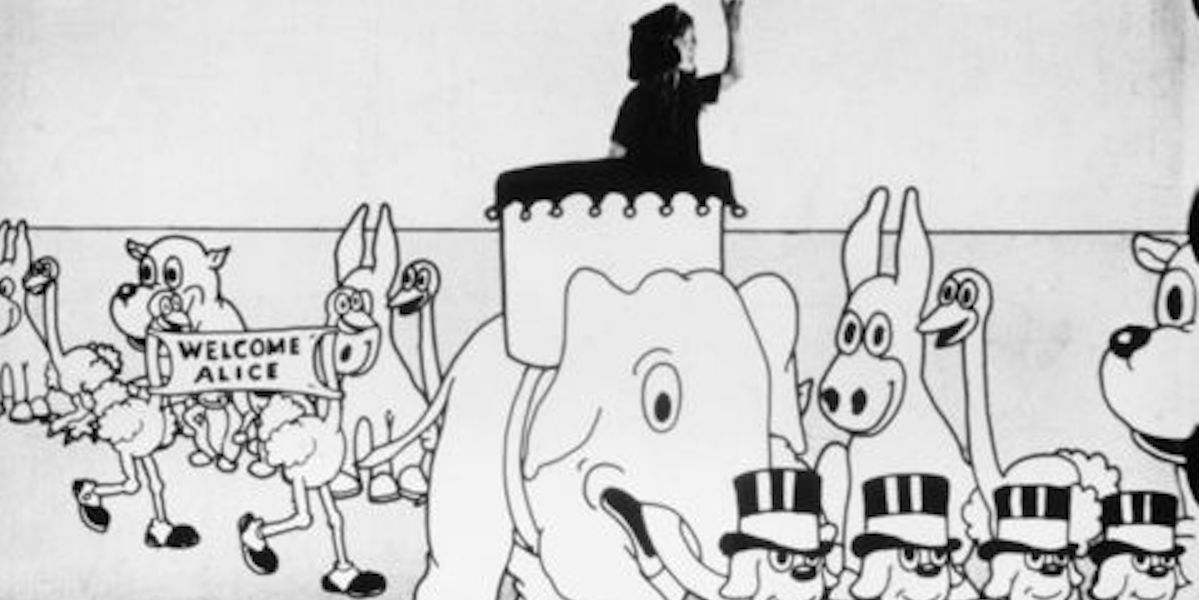

A major turning point in Walt and Iwerks’ relationship, and in the Disney studio, came when Walt lured Iwerks to California in 1924. Each had developed in their year apart. Walt, now partnered with his big brother Roy Disney, came to recognize he was a better gag man and director/producer than a cartoonist, while Iwerks had become an efficient and rapid animator – not as loose or inventive as the East Coast competition, perhaps, but every bit their technical peer, as Walt was happy to argue to distributors in those days. His presence at the Disney Brothers Studio almost singlehandedly raised the visual quality of the Alice Comedies series and sped up their rate of production. By taking over the last of Walt’s animation chores, Iwerks also freed the boss up to develop scenarios and the beginnings of personality in their animated characters. The Oswald the Lucky Rabbit series was a showcase for their growing respective talents.

Oswald also occasioned a display of just how well Iwerks understood his friend and employer. While Walt could still fraternize with his staff, the pressures of running a studio sometimes brought out his irascible side. His perfectionist streak and manic devotion to work also took their toll on the staff, still made up of young men finding their footing. Where others took offense and walked out, Iwerks let the mood swings wash over him and suggested the rest of the staff do the same. When distributor Charles Mintz decided he could directly produce Oswalds for Universal Studios and moved to hire away all Walt’s workers, Iwerks was the only prominent animator to stay loyal to the Disneys. Besides his long connection with Walt, he’d invested part of his salary in the company; he was a 20-percent owner.

Which brings us to the creation of Mickey Mouse. Legend, studio publicity, and Walt Disney himself held that Mickey was born on the train ride Walt took back from New York after his failed negotiations with Mintz, with no mention of Iwerks’ role. Within animation circles, where Iwerks’ involvement is known, there’s sometimes been a tendency to give him full credit, with Walt the conniving Bob Kane to Iwerks’ put-upon Bill Finger. Chester Lampwick was built around that assumption.

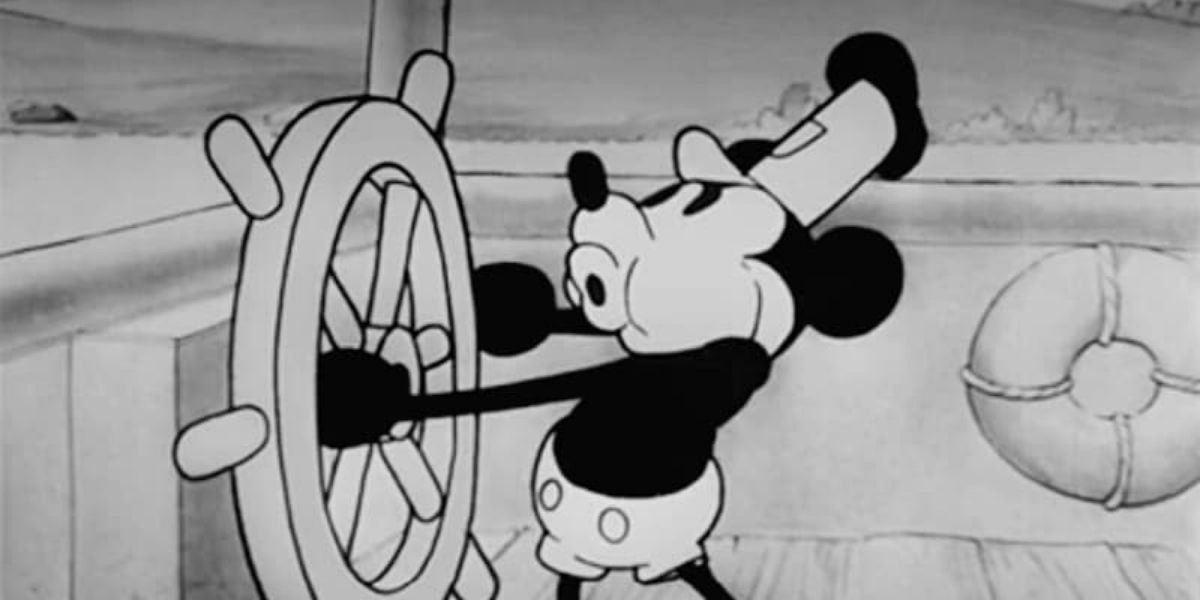

The likely truth is that Mickey was the son of two fathers, Walt and Iwerks, who sat in a room with Roy and struggled to come up with a replacement character for Oswald, one who was initially nothing special. Mice had featured in the Alice Comedies and in publicity material for Oswald, and Mickey share the same basic round inkblot base as Oswald and many other cartoon characters at the time – he just had the ears and nose swapped out. Recollections varied over the years, but it does seem that, after Walt settled on a mouse and attempted to draw him, Iwerks created the final design. He was the only animator on the earliest Mickey Mouse films, which are credited as “A Walt Disney Comic by Ub Iwerks.” When in New York on business, Walt would write back that Iwerks’ odd name was an asset in advertising and that the Manhattan animators tipped their hat to Iwerks’ talent.

But what set Mickey apart from the pack and launched Disney as a premiere cartoon studio was sound and personality. The idea for synchronizing sound and picture in animation, Mickey’s falsetto voice, and his plucky, optimistic personality all came from Walt, who continued to sharpen his narrative and comedic instincts. As the studio grew and as animation developed as an art form, Iwerks proved resistant to change. He wouldn’t accommodate having in-betweeners take over a portion of the workload, and he and Walt began to clash over changes Walt made to the timing of his animation. While both had had a hand in Mickey’s creation, Iwerks also felt overshadowed and taken for granted. A possibly apocryphal story passed around holds that, at a part, Walt was asked by a child to draw Mickey. Walt passed the pen and paper to Iwerks and told him to do the drawing; he, Walt, would sign it. “Draw your own Mickey,” Iwerks snapped.

Whether that ever happened or not, when sound man and distributor Pat Powers attempted the same trick Charles Mintz had pulled, Iwerks was ready to leave the Disneys. It isn’t clear whether Powers thought Iwerks was the power behind the throne or if he just wanted to use Iwerks as a bargaining chip with Walt, but either way, he was prepared to set up a studio for him, and Iwerks took the bait. He explained his feelings to Roy but never had it out with Walt, who in turn never contacted Iwerks but complained furiously about losing him. The 20-percent stake was bought back, Iwerks Studio was launched in 1930, and that seemed to be that.

But Iwerks’ skills as a manager and businessman hadn’t improved any since the Iwerks-Disney days, and he still didn’t have much of a sense of humor. Animation across the board was gravitating toward more organic and fluid movement than he could produce. His cartoons floundered. And the split with Walt just didn’t sit right with Iwerks. He’d told Roy when he left that he never would have gone with Powers if he’d known how it would work out. As for Walt, who grew more paternalistic and detached from his staff with time, people who knew him were sure he loved his old friend.

So, when Iwerks was hired back by supervising director Ben Sharpsteen as an animation checker in 1940, he and Walt (after some maneuvering by Sharpsteen) got together for lunch. Neither was inclined to show too much affection in their friendships, but they seemed to have an unspoken agreement to leave the past behind. When Walt asked Iwerks what he wanted to do, Iwerks said: “Prowl around.” He was always less manic than Walt about – well, about everything, but animation specifically. Technology caught his attention more (some who worked with Iwerks unkindly compared him to a machine or automaton, he was so remote).

Walt put him to work on special effects, and it was there that Iwerks delivered his longest service to the Disney studio. He built optical printers for combining live action and animation. He used the same techniques to replicate Hayley Mills in The Parent Trap and for matte work. When Disneyland and the New York World’s Fair opened up possibilities for Audio-Animatronics, Iwerks became involved that field. And, in the 1960s, Iwerks saved Disney animation by developing the Xerox process for transferring animation drawings directly onto clear cels, saving a fortune on ink and paint costs. He stayed with the studio even after Walt’s death, contributing to Walt Disney World’s development until he died in 1971.