Like Matthew Pires (Letters, 24 April), I too studied The Mayor of Casterbridge for O-level and incidentally hated it until I had to reread it a couple of years ago while doing research for a production of it by the New Hardy Players in Dorchester.

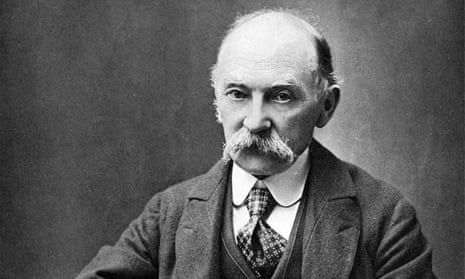

While I agree that Michael Henchard is a misogynist, I would argue that the novel does not share Henchard’s worldview, and in fact Henchard isn’t the focus of the novel. Thomas Hardy, despite his own problematic relationships with women, was a champion of women’s rights. His novel The Woodlanders, for instance, tackled the unfairness of divorce law at the time.

In The Mayor of Casterbridge, he created a strong woman in Henchard’s illegitimate stepdaughter, Elizabeth-Jane, who I believe is the real protagonist. Through her and the other women in the novel, Hardy critiques the male worldview. We see Casterbridge through Elizabeth-Jane’s eyes. We eavesdrop on her internal world. Throughout the novel, we are reminded of her thoughtfulness and intelligence. Henchard’s journey from disreputable drunk to “man of character” is inextricably linked to his growing appreciation/love of Elizabeth-Jane.

By the end, Henchard is dead. Elizabeth-Jane, now happily married and comfortable, is “forced to class herself among the fortunate”. She retains a sense of wonder that, for one whose broken childhood had taught her “happiness was but the occasional episode in a general drama of pain”, her adult life has become one of “unbroken tranquillity”. For a Hardy novel, that is an unusually happy ending, and it is one without judgment on her as a woman or as a lowly-born illegitimate child – unusual for Victorian Britain.

Liz Bennett

Dorchester, Dorset