The Spanish photographer who captured the horrors of Mauthausen

Francisco Boix rescued hundreds of images of life in the Austrian concentration camp

Seventy years ago, on May 5, 1945, US troops liberated Mauthausen-Gusen, the hub of a large group of German concentration camps in Upper Austria, roughly 20 kilometers east of the city of Linz, on the river Danube. The complex had been built within months of Germany’s annexation of Austria in March 1938, and over the next seven years, almost half of the 200,000 prisoners who passed through Mauthausen died.

Boix gave evidence at the Nuremberg trials in 1946, saying he had hidden 20,000 negatives of life in the camp

Mauthausen was also where the Germans sent many of their Spanish political prisoners. An estimated 7,000 Spaniards were shipped there, many of whom had previously been held in camps by the French government and handed over to the Germans in 1940, after France capitulated. Many thousands more were sent to other camps in Germany and Austria.

The majority of the Spanish prisoners at Mauthausen were detailed to quarries where they were worked to death under slave-labor conditions, but a few more fortunate individuals were given administrative jobs. Among them was Barcelona-born Francesco Boix Campo, who arrived at Mauthausen in January 1941, aged 20. Able to speak German, Boix initially worked as a translator, but later, thanks to his photographic skills, was eventually assigned to work in the camp’s photo laboratory.

Boix was there when the Americans entered the camp, and had already begun taking dozens of photographs of the first hours after the German and Austrian guards fled, and would capture life in the camp in the weeks that followed.

But Boix made another, arguably more important contribution to history. Along with other prisoners, and a local woman called Anna Pointner, who had helped prisoners during the war by throwing food over the fence, he rescued hundreds of negatives depicting daily life in the camp over the years.

A new edition of El fotográfo del horror (or, The photographer of the horror), originally published in 2002 by historian Benito Bermejo, tells the story of Boix’s time in Mauthausen, and also includes his photographs from the Spanish Civil War.

Boix risked his life by disobeying orders issued after the German defeat at Stalingrad in early 1943 – the turning point in the war – to destroy all photographic evidence of life, and death, in Mauthausen and its surrounding camps. He gave evidence at the Nuremberg trials in 1946, saying he had hidden 20,000 negatives, around a third of the photographic archive, with the help of other Spaniards, although barely 1,000 of them survived. In the fall of 1944, groups of prisoners sent out of the camp to work were able to pass on piles of negatives to Anna Pointner. A small memorial was subsequently erected in the camp to honor Pointner’s bravery.

After the war, Boix published some of the photographs in French magazines, as well as allowing them to be used in a number of books.

But Boix never fully recovered from his experiences, and died aged 30 in Paris in 1951. During those six years he worked as a reporter for the Communist Party newspaper L’Humanité – he remained a member of the party – as well as other publications such as Regards and Ce Soir. He also published a volume of memoirs, entitled Spaniaker, the term used by the Germans to describe the Spanish prisoners at Mauthausen.

Death by the Danube

- In August 1938, the camp received its first prisoners, most of whom were common criminals, many transferred from Dachau, near Munich. When the camp was liberated by US troops on May 5, 1945, some 200,000 prisoners, including women and children, had passed through; around half died.

- In 1940, another camp was built at Gusen, around five kilometers away. Like at Mauthausen, most inmates were sent to work in the nearby Wienergraben quarries under brutal conditions, and were literally worked to death.

- The granite hewn from the quarries was used to build the Nazi regime's monumental works. From 1942, inmates were used for war work, much of it in factories built in huge tunnels excavated in the surrounding hillsides to avoid allied bombing.

- Of the 7,000 Spaniards sent to Mauthausen, Gusen, and nearby Hartheim Castle, 4,672 died.

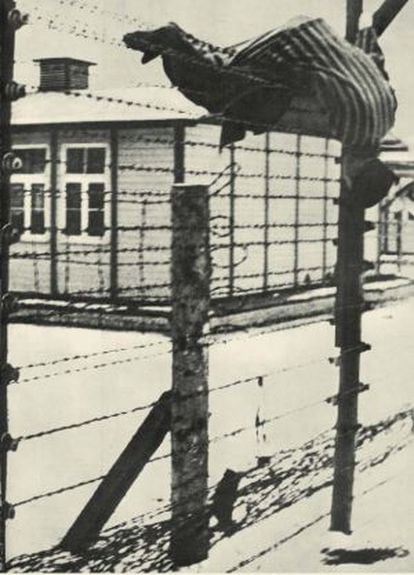

- The SS guards who ran the camp came not only from Germany and Austria, but were also recruited from Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. The camp commandant, Franz Ziereis, tried to flee as the allies advanced, but was shot and wounded, and died while being interrogated. His body was later thrown on to the camp fence where it was left for several days before being cremated.

- A report made after the camp was liberated included a list provided by an Austrian inmate of the ways prisoners were killed, among them were: gas chamber, gas van, lethal injection, being torn apart by dogs, cold showers in winter, and a shot to the temple. Thousands of prisoners also committed suicide by various means.