From the July 2013 issue of Car and Driver

“It’s reality plus 30 percent,” explains Justin Lin about the outsize action in the four Fast & Furious films he has directed. “We take everything that step beyond.” However, that step beyond, that leap from live action to full seat-rattling mayhem, takes people, cars, two years, logistics that span the globe, and a thick layer of technology. Plus bags and bags of cash.

This isn’t the early 1970s, when a relatively small crew could film street-level mayhem on a shoestring. And today’s audiences won’t accept the crappy, computer-generated car imagery that was the standard a decade ago. State of the art in 2013 means combining elements lavishly filmed at locations around the world with digital effects carefully crafted to blend in unnoticed.

Lin’s latest—and, likely, last—film in the series is Fast & Furious 6, basically a chase and heist action flick that opened today, May 24 and features what are probably the most technically ambitious and expensive car sequences ever filmed. F&F 6 pushes the plausibility of car action that extra 30 percent with hundreds of speeding, spinning, and flying cars. Presented here step by step, and skipping only a few hundred steps, is one chase in the film, from the writer’s notion to the full, finished frenzy.

The sequence we’ve chosen features the familiar Fast & Furious team of daring motorheads up against its evil doppelgängers, a mob of ruthless car-mad criminals. It starts with a massive explosion, proceeds to wipe out a load of British police cars and BMW M5s, and winds up (semi-spoiler alert) with a character returning from the dead to shoot Vin Diesel. Because, well, of course it does.

This all started when money rained in a vast, unexpected deluge following the 2001 debut of The Fast and the Furious. It was, by entertainment-industry standards, a relatively cheap, $38 million exploitation flick built to cash in on the then-current import-tuner craze. It was No. 1 at the box office on opening weekend and went on to take in $144.5 million in the United States and another $62 million in the rest of the world. The sequel machine was then cranked up, and 2003’s 2 Fast 2 Furious made even more money, despite the fact that star Diesel skipped it altogether.

Lin’s first F&F film, 2006’s The Fast and The Furious: Tokyo Drift, only did so-so in the U.S. but pulled in $96 million overseas. Then in 2009, the fourth film, Fast & Furious, raked in an incredible $363.2 million worldwide. The most recent installment, Fast Five (2011), garnered an astonishing $626.1 million. That’s the kind of trend line that keeps Hollywood open for business. In total, the first five F&F films have grossed almost $1.6 billion.

With the films firmly entrenched as Universal’s dead-certain moneymakers, the studio rehired Lin, now 41, to spend something like $160 million to make Fast & Furious 6, although Universal doesn’t discuss budgets. And spend he did.

Working in a Burbank, California, coffee shop on his laptop one day in 2011, screenwriter Chris Morgan drafted the scene that would eventually evolve into what we’re calling the “flip-car” chase through London.

“The intent was always to have a vehicle as a weapon,” Morgan explains. “Originally it was going to be a Mercedes G-wagen, and it basically had a ramp that would fold down from the top. And then, talking to Justin and [picture car coordinator] Dennis McCarthy, we thought, ‘Well, what about an F1 [racer]? What about a low-slung kind of thing?’ ”

The resulting design is McCarthy’s own. While location scouting proceeded in Great Britain early in 2012, his crew started building seven of the tube-frame flip cars at a 20,000-square-foot shop hard against the Burbank Airport in California’s San Fernando Valley.

With the front suspension from a mid-1980s Chevrolet three-quarter-ton pickup truck and a solid rear axle located by a three-link suspension, each of the mid-engine flip cars is powered by a 430-hp 6.2-liter LS3 V-8 crate engine straight out of the GM Performance Parts catalog. Mounted backward in the fabricated chassis, the LS3 feeds a Turbo Hydra-Matic 400 three-speed automatic transmission. A Casale V-drive mounted just behind the driver takes power from the transmission and sends it back to the Dana 60 rear axle. It’s the wedge shape of the flip cars that makes them dangerous; they submarine under ordinary vehicles to flip them up in the air. And it’s their four-wheel hydraulic steering that allows them to crab across roads and position themselves for attack. In the story, the flip cars are piloted by a driving team at least as good as the series’ continuing heroes, albeit nastier and more, y’know, villian-y.

“These guys are supposed to be the shadowy reflections of our heroes,” Morgan adds. “They build their own cars. They hyper-tune these things. The cars they use are purpose-built.” Introducing these bad guys and informing the audience of their villainous precision and competence is the main plot function of the chase.

The good guys—including Diesel and his pecs, and Paul Walker and his super-dreamy blue eyes—are in five black M5s. Or, at least, regular E60 5-series tweaked to resemble M5s. Plus there’s former wrestler and F&F veteran Dwayne Johnson rocking a Navistar MXT military truck and also leaping off it. And why the hell not?

The discovery by the film’s location scouts of a tiered, abandoned construction site in London inspired the chase’s opening moments. It’s from this location that the action starts, with top bad guy Owen Shaw (actor Luke Evans) luring most of British law enforcement to the site and then blowing it up.

Some of the subsequent action was developed during practice by Greg Powell’s mostly British stunt team as it rehearsed with the difficult-to-master flip cars at Longcross Proving Ground near London.

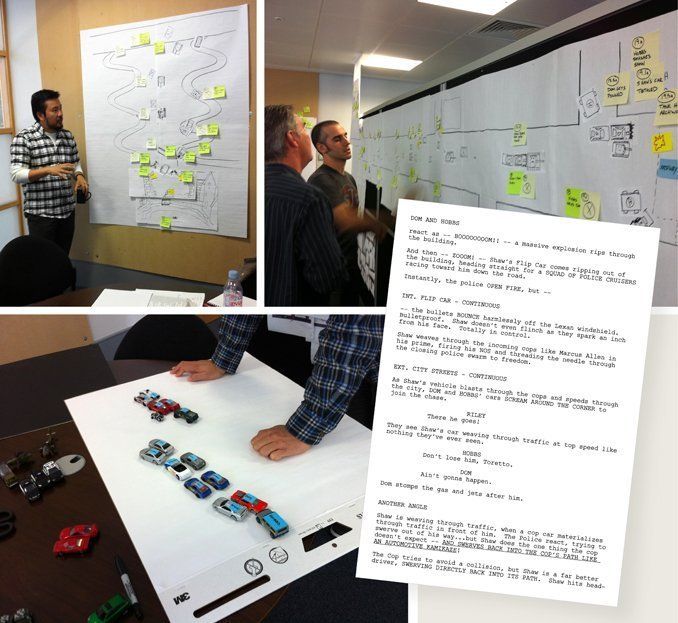

"The streets of London, Liverpool, and Glasgow [where the chase was filmed] are very narrow," says Powell, 59, whose daughter Tilly, now 21, drove one of the flip cars. “That’s why we did so many rehearsals. During testing we sort of come up with ideas. Occasionally I had to show the young ones how it’s done.” But the bulk of the scene’s planning had director Lin using storyboards, visualization and animation software, and occasionally a couple of Hot Wheels atop a white board.

Meanwhile, because only small portions of London’s streets can be closed at any one time and Glasgow doesn’t necessarily always look like London, the special-effects department carefully measured every aspect of the filming sites using conventional surveying tools and LIDAR measurement systems. That was done in order to plan the action correctly, and so that scenes can be visually extended using computer graphics. Thus, a 900-foot run down a street will look a mile long in the finished film. With computer-generated buildings and other landscape details, Glasgow and London, plus a tunnel in Liverpool, blend together into one believable pseudo-London. The measuring work was painstaking; missing anything could screw up the computer rendering later.

“This is visual effects in a supporting role,” explains visual-effects supervisor Kelvin McIlwain. “We’re here to help Justin go out and shoot as much, practically, as he can.” So while the cars in the chase sequences are real, the city around them is often fake. “There is no substitute for reality,” concludes McIlwain, “But it’s not always possible.”

Besides Universal’s own effects department, 10 other far-flung special-effects vendors worked on the film, including Double Negative Visual Effects in London and companies in Singapore and New Orleans. More than 1000 people working in those shops helped craft the film.

It took four weeks during August and September of 2012 to shoot the flip-car chase in the U.K. Over that time, the crew would capture about 300 individual shots and wreck about a dozen Vauxhall cop cars. There were 14 BMW 5-series on set, 11 of which were destroyed.

“We had over 20 drivers,” says stunt coordinator Powell, “including Ben Collins, who used to be The Stig on BBC’s Top Gear.”

The wrecks and car flips themselves weren’t unusual. Traditional ramps made out of tubular steel trusses and under-car cannons launched the cars into the air. But the sheer number of cars that worked together was daunting. And the sequence’s unique, signature stunt—driving one of the flip cars underneath another car—may have taken more sheer guts than any other.

“Mark Higgins was in the flip car for that,” says Powell. “We had mounted a pipe ramp to it, but remember, it’s not like it’s a closed car. And he drove into the other cars at like 30 mph. That takes balls.”

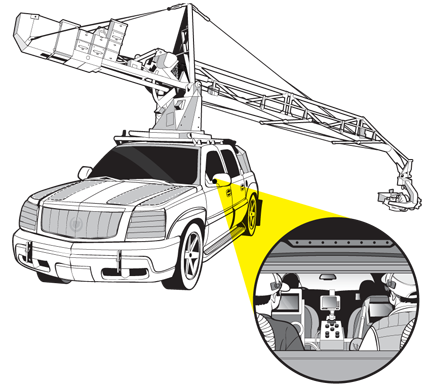

Some of the scenes were shot with up to 12 different cameras running, some of which were mounted to high-speed Porsche Cayenne, Cadillac Escalade, and Mercedes M-class high-speed camera cars. Cameras were also mounted to the action car and on cranes and dollies. Meanwhile, the actors were shot on a process stage in Middlesex, England, sitting in cars mounted against a green screen on multidirectional gimbals. They would be digitally inserted into the scene later.

“We did an enormous amount of visual janitorial work,” says McIlwain. “Every single shot in this chase has been touched. We re-speeded some shots to give it a little bit of a boost, making it seem like the car’s moving faster.” The effects crew also digitally deleted camera cars from the background and camera rigs from the sides of cars. But not only were the camera cars and rigs removed, their reflections had to be digitally erased from surfaces, too.

For the cars shot with actors on the green-screen stage, the visual-effects team added reflections to make the movement seem real. “We shoot the cars on stage without windshields or door glass,” McIlwain explains, because “you can’t get rid of some reflections. So we have to add in digital glass to those cars, too.”

The most intense visual-effects work, though, was spent on the opening scene at the construction site. “That entire implosion is CGI,” says McIlwain, referring to computer-generated imagery, “and it has been painful getting it to the state it’s in. We had a very definite idea that everything had to have some basis in reality. So we documented the hell out of that place. We brought in a LIDAR scanner and created a 3-D representation as the basis for creating the destruction. We had to work out how the hard parts of the architecture would collapse.” Created by simulation software and tweaked for dramatic effect, the result is convincing, right down to how the digital police cars bounce atop the rubble.

There are no digital substitutes for sounds, however. And there were no automotive, explosive, or concussive sounds recorded during the filming. Instead, sound editor Peter Brown and his crew created the audio track from sound samples they took from libraries or had gathered themselves by driving cars at a desert airport in California City, California.

“We used Mike Ryan’s Freightliner Pikes Peak race semi for the Navistar’s audio because it sounds awesome. And we used an M5 and an X6 for the sounds of the M5s. It’s finding the right sound for the flip cars that’s been toughest.”

Throw in hundreds of hours of editing, color correction, dialogue recording, and a musical score, and the result is what everyone sees in the theater.

Lin’s team likely spent at least $20 million producing the seven or so minutes of the flip-car chase. If they keep this up, pretty soon they’ll be talking serious money.

John Pearley Huffman has been writing about cars since 1990 and is getting okay at it. Besides Car and Driver, his work has appeared in the New York Times and more than 100 automotive publications and websites. A graduate of UC Santa Barbara, he still lives near that campus with his wife and two children. He owns a pair of Toyota Tundras and two Siberian huskies. He used to have a Nova and a Camaro.