"Fifty Years of the Rolling Stones", "Fifty Years of 007", "Fifty Years of the Beatles" – as a 49 year-old I feel a little resentful of the latest round of anniversaries. They might as well write: "Hey, something really exciting and important happened here and you just (but only just) missed it. Ha, ha." If there is no future any more, then at least we can celebrate anniversaries. The fact that a particular number of years has passed since an event appears to confer on it a certain gravitas and significance. (Though I'm sure I saw an advert for a Pretty Things reunion concert a couple of years ago that proclaimed "43 years since the release of SF Sorrow" or something similar.) We are children of the echo. Born just after some kind of explosion, and doomed to spend our lives working backwards to try and get as close as we can to the moment of that Big Bang. Now, a cosmologist will tell you that he knows what was happening in the universe a trillionth of a second after the big bang but he still can't explain the bang itself. And so it is for the commited Beatles-ologist – just how did those four lads come to "shake the world"? And shake it so hard? Will we ever know?

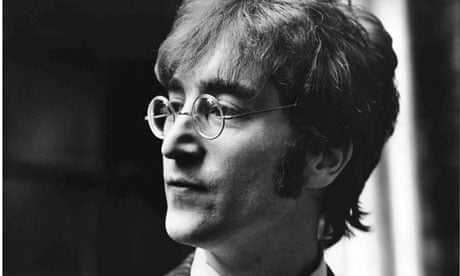

Maybe this might help to clear things up: The John Lennon Letters, put together by Hunter Davies, the guy who wrote the very first Beatles biography (which came out ages ago – like, you know, when they still existed). The earliest letter dates from 1951, the last from 1980. Everything happened between those dates – Hamburg, Beatlemania, Ed Sullivan, the Maharishi, Bagism, "Imagine", you name it – and Lennon found the time to write letters about it? Awesome! Well … not quite.

To be fair to Davies, he does admit in his introduction that he has "rather expanded the definition of the word 'letter'". This still does not quite prepare the reader for gems such as "Degs, No Fucking George, Yer Cunt, Jack" (letter 238: Memo to Derek) or "Fred, Lights in kitchen (bulbs), Honey Candy, Kitchen Air Con is 'On Heat' (Something Wrong), Cabbage, Grape-oil (ask where), Onions, Peas (NB the Korean Shop Shells Them!), Sesame Oil, Tomatoes, Berries, Yoghurt, Hamburger Meat (for the cat!)" (letter 255: Domestic list for Fred). The Post-It Notes of John Lennon, anyone? I like mundane reality – you could say it's my specialist subject – but there's no getting away from the fact that the second of those two examples is a shopping list. Are we really so bereft of new ideas that we now wish to study the equivalent of someone's Ocado profile?

A clue may lie in the sources that Davies has used for this book: in the main the letters came not from their original recipients, but from private collectors who had acquired them at auction. In the years since they were written, these communications have turned from scraps of paper into banknotes. They are valuable objects. Hence each is represented by a photo of it accompanied by a transcription of its contents. The photo of the artefact is just as important as what it actually says (maybe more so). The photo is saying: "Look at this – this piece of paper is worth thousands of pounds! A famous person once touched it!" And perhaps that message is more important than the wording of the letter itself. It's a book of religious relics rather than some form of autobiography. Or maybe it's just a posh version of a Sotheby's catalogue.

Am I being too harsh? Let me get one thing straight: I love the Beatles. I haven't named any kids after them but I still really love them. They were the first group that I was ever properly aware of. In my early teens I would sometimes stay in and listen to the radio all day in the hope that I would catch a song by them that I'd never heard before and be able to tape it on my radio-cassette player. When I bought a new turntable last week, I took along my copy of Abbey Road to do a listening test. It was essential to me that that record would sound good on whatever I bought. But the whole point of the Beatles is that they were ordinary. Four working-class boys from Liverpool who showed that not only could they create art that stood comparison with that produced by "the establishment" – they could create art that pissed all over it. From the ranks of the supposedly uncouth, unwashed barbarians came the greatest creative force of the 20th century. It wasn't meant to be that way. It wasn't officially sanctioned. But it happened – and that gave countless others from similar backgrounds the nerve to try it themselves. Their effect on music and society at large is incalculable. I am so the target-audience for this book that it hurts – but something feels wrong.

Britpop (I can scarcely believe that I typed that word of my own free will) perhaps comes in useful for once at this point. People of my generation felt this obscure pang – this feeling that we'd somehow missed out on something amazing. So we tried to make it happen again – but exactly the same. You cannot do a karaoke version of a social revolution (good fun trying though). What changed in the interim? Why was Br**pop doomed to failure? Too many factors to go into here, but one was: too much information. Too much reverence. Wearing the same clothes and taking the same drugs will not make us into Beatles. It will make us fat and ill. And books like this (along with many others, I admit) are what make that mistake possible. The Beatles didn't know they were the Beatles. The Beatles didn't have a plan or a blueprint to follow. They followed their impulses and vague hunches and somehow left a legacy of 213 songs with scarcely a dud among them. That's all the information you need, really. But now that relatively modest body of work has been overshadowed by all the "previously unseen" and "the making-of" nonsense that becomes necessary if you want to flog people the same thing year after year.

We elevate people to the status of heroes in order to let ourselves off the hook: "I'm just a mere mortal – I could never even dream of doing something like that." Lennon himself always seemed at pains to deflate any such high opinions of himself: what he would make of this book, I can only guess. The letters show an ordinary human being doing ordinary things: writing lists, sending postcards, enquiring after relatives. Why is that interesting? Because that person has now achieved demigod status. Is that a good thing? I dunno – good singer, though. Pretty good songwriter too, as it goes …

You, Hunter Davies, are just doing your job. I read it from cover to cover and will probably give it as a Christmas present. We, the children of the echo, should get a life. We, the children of the echo, should know better. Time to move on. Imagine that.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion