These notes accompany The Chaplin Revue, which screens on January 20, 21, and 22 in Theater 3.

I’ve written more about Charles Chaplin than about any other filmmaker (including the book Charles Chaplin: An Appreciation, published by MoMA in 1989), and I’m not exactly sure where to begin now. Certainly, he is the auteur’s auteur, having had more freedom than any other director to visualize on celluloid what he dreamed and imagined. This was the lucky consequence of being the most famous artist in the world, allowing him to purchase his own studio, rehearse endlessly, and save for his audience only that which he considered to be up to his standards. The great Jean Renoir said: “The master of masters, the film-maker of film-makers, for me is still Charlie Chaplin…Clifford Odets telephoned that he wanted us to meet the Chaplins. It was like inviting a devout Christian to meet God in person.” Rene Clair said that Chaplin was so “profoundly original” that he had little direct influence on the cinema, but that without Chaplin, “we would not have been altogether the same people we are today.” I share many of these feelings.

“Feelings” is, of course, the key word in evaluating Chaplin’s art. Surely, he was a skilled director, always knowing (as the super cinematographer Nestor Almendros told me) the precise location to place his camera. Surely no other director tackled the great issues of his time—war, mechanization, poverty, fascism, nuclear weapons, McCarthyism, old age—more directly or with greater passion. When all is said, however, the heart of his genius was his acting, and he has no genuine rival when it comes to intensity and depth of performance. As Andrew Sarris said, Chaplin’s face was his mise-en-scène. D. W. Griffith could extract superlative performances from a swath of actors and he fully understood the power of film to engage its audience emotionally, but none could touch Chaplin’s ability to move us, to involve us completely with what he was experiencing and thinking, to be (as Clair said) “our friend.” As empathetic as Griffith was with his actors, no relationship could compete with the intimacy Chaplin the director shared with Chaplin the actor. He was helped enormously by appearing as essentially the same character in all but his last four films. And of these, Monsieur Verdoux (1947), Limelight (1952), and A King in New York (1957) are as autobiographical as any works by a major director. Although he stepped out of the character of The Tramp for good at the end of The Great Dictator (1940), our “friend” had already become our lifelong companion.

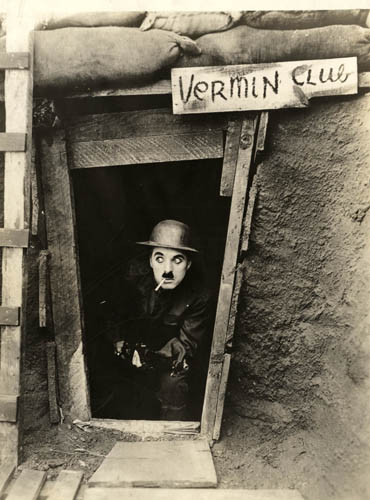

In order to grasp this (because language will not suffice), one must see the films. Chaplin’s methodology, technique, theories—whatever—cannot be taught in film school. He was inimitable, and we will never see his like again. Although one can see his developing command of the medium in the Keystone, Essanay, and Mutual shorts he made in his late twenties, it is only with longer films that the stamp of genius begins to seem inadequate. Shoulder Arms and A Dog’s Life mark the turning point. The former is as funny as any film ever made about that least funny subject: war. And in the latter Charlie mistakes a man’s crying for laughter; his whole life and career are a commentary on the frail membrane that separates the two.

In The Pilgrim, The Tramp is an escaped convict masquerading as a preacher. There is something almost self-deprecating in an extraordinary tracking shot (camera movement was rare in his work) in which a naughty boy knowingly looks at the camera and then deliberately throws a banana peel in the path of Charlie and the fat deacon (Mack Swain). Of course, both obligingly slip and fall, and it is funny, even more so for our anticipation. However, by having the boy acknowledge the camera and, hence, our presence, Chaplin seems to be telling us that pratfalls are now too easy for him—his facility with such nonsense has become too great—and he must move on to bigger things.

Chaplin famously defied the coming of the talking picture. However, City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936) did have a soundtrack of Chaplin-composed music. While his scores may not be up to classical standards, they have become an integral part of these films, totally idiosyncratic and, yes, Chaplinesque. Later, he added his music to his earlier work, including (in 1959) his compilation of the three films in this program, packaged as The Chaplin Revue. The Chaplin Office, which oversees Charlie’s cinematic legacy, informs me that a major re-release of the post-1917 films is forthcoming, and we all should be looking forward to this. Although the films have been generally available in recent years, this is likely to be one of the major film events of the decade. When Chaplin withheld his films in the years following his exile to Switzerland, their re-release in the early 1960s proved to be a life-changing experience for me.