The Bridge on the River Kwai

Brief Synopsis

Cast & Crew

David Lean

William Holden

Alec Guinness

Jack Hawkins

Sessue Hayakawa

James Donald

Film Details

Technical Specs

Synopsis

In World War II Burma, after they are captured by Japanese troops during World War II, British commander Col. Nicholson and his troops march into Prisoner of War Camp 16 whistling their regimental tune. Their crisp arrival is wryly observed by Shears, an American sailor who bribes a guard to transfer him from the burial detail to the infirmary. When the camp's commander, Col. Saito, imperiously informs the new prisoners that they will all be expected to work on building a railroad that will connect Bangkok to Rangoon, Nicholson protests that under the regulations of the Geneva Convention, all officers are exempt from manual labor. Afterward, Nicholson goes to the infirmary to visit Jennings, one of his wounded men. There Maj. Clipton, the camp's medical officer, introduces the colonel to "Commander Major" Shears. When Jennings proposes escaping, Nicholson counters that he was ordered by headquarters to surrender, and therefore escaping would constitute a military infraction. Incredulous at the colonel's naïveté, Shears retorts that escape is their only chance to avoid the death sentence of forced labor. The following day, Saito announces that all the men, including officers, will work on building a bridge across the River Kwai. When Nicholson defiantly waves a copy of the Geneva Convention, Saito slaps him across the face with it and flings it to the ground. Nicholson still refuses to let his officers perform manual labor, and after the other men march off to work, Saito calls for a machine gun and threatens to gun down all the officers. Watching in horror, Clipton runs out of the infirmary and protests that he and his patients have seen everything and will be witnesess to murder if Saito orders the gunners to fire. Saito then changes his mind and forces the officers to stand for the entire day in the merciless sun. Afterward, Saito locks Nicholson in "the oven," a crude metal shed, and imprisons the other officers in the "punishment hut." As the troops encourage Nicholson with a rendition of "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow," Shears, Jennings and a prisoner named Weaver escape into the jungle. Jennings and Weaver are gunned down by the guards, who then pursue Shears to a ridge above the river and shoot him. The guards assume that Shears is dead after he plunges into the river, but he survives and makes his way down river to the shore. Later, Saito summons Clipton and asks him to tell Nicholson that unless he cooperates, the patients in the infirmary will be forced to work. Confronted with the ultimatum, Nicholson still refuses to comply on the grounds that "it is a matter of principle." With only two months left before the May first deadline for the completion of the bridge, Saito, frustrated by the slow progress, takes command of the project himself. After a segment of the bridge collapses, a defeated Saito has Nicholson brought to his office from the oven and explains that if he fails to meet the deadline, he will be forced to commit hara-kari. Unmoved, Nicholson insists that the Geneva Convention be adhered to, after which Saito orders him taken back to the oven. Meanwhile Shears, who was found near death by some friendly villagers, recovers and begins a solitary boat trip down river. Days later, his water exhausted, Shears passes out, leaving his boat to drift aimlessly. Plagued by ineptness and sabotage in his efforts to build the bridge, Saito orders the weakened and dehydrated Nicholson pulled from the oven and brought to his office where he grants a general amnesty to the officers and declares it will not be necessary for them to perform manual labor. As the men cheer Nicholson's victory, Saito sits in his office, broken and sobbing. Upon inspecting the bridge, Nicholson criticizes the workers' cavalier attitude and asks Capt. Reeves, who worked as a civilian engineer, for advice. Reeves observes that the river bottom at the present location is soft mud and suggests moving downstream where the bottom is solid bedrock. When Maj. Hughes, a public works engineer, criticizes the men's lack of teamwork, Nicholson declares that they will rebuild the company's morale by building an exemplary bridge. Nicholson, completely oblivious to the fact that he is about to aid and abet the enemy, presents a plan to Saito increasing the men's daily work quota and suggests that Japanese soldiers should work laying track. Seeing his position crumbling, Saito stoicly says that he has already given the order. Shears, meanwhile, has been picked up by a sea rescue plane and brought to a hospital in Ceylon where he is visited by Maj. Warden, the explosives instructor at a nearby British commando school, who invites him to a meeting at the school. At the meeting, Warden explains that he plans to lead a team into Burma to blow up the bridge and asks Shears to join them. Shears, desirous of returning to civilian life, demurs, confessing that he was merely impersonating an officer and therefore is not qualified for the mission. Warden then informs him that the U.S. Navy already knows about his deception and has authorized his transfer to the British commandoes. Faced with possible imprisonment for impersonating an officer, Shears reluctantly accepts the assignment and retains his rank as Major. At the prison camp, Clifton warns Nicholson that he could be charged with treason for collaborating with the enemy. Obsessed by proving the mettle of his British soldiers, Nicholson turns a deaf ear to the medic's protest. At the commando school meanwhile, Shears joins a team comprised of Warden, Chapman and Lt. Joyce, a young recruit wary of killing. As the four parachute into the jungle, Chapman crashes into a tree and is killed. The others are met by Yai, a native guide who hates the Japanese, and four women bearers. As they begin their trek through the jungle, they receive a radio transmission from headquarters informing them that a special train carrying troops and VIPs is scheduled to inaugurate the bridge on the thirteenth, and ordering them to carry out the demolition on that day. Realizing that he cannot finish the bridge by the deadline, Nicholson matter-of-factly tells Clifton that he has asked the officers to work beside the enlisted men and they have volunteered "to a man." After Clifton's protests, Nicholson then recruits wounded men from the infirmary to perform "light labor." In the jungle, meanwhile, Warden's team is accosted by Japanese soldiers, and in the skirmish Warden is shot in the ankle. Warden subsequently stumbles along on his crippled foot, climbing torturous mountain paths, but when they are just six hours away from the bridge, he declares that the others should continue on without him. Angrily denouncing Warden's self-sacrifice as the histrionics of a British gentleman, Shears orders him hoisted onto a stretcher, after which they all continue on together, reaching the bridge just as Nicholson is nailing up a plaque commemorating the work of the British soldiers. That night, as the prisoners put on a show in celebration of the completion of the bridge, concluding with "God Bless the King," Joyce and Shears, aided by the women, pilot a raft filled with plastic explosives to the bridge while Saito, having been bested by the British, makes preparations for hara-kari. After attaching the explosives to the bridge, Joyce takes cover with the detonator while Shears swims back across the river to await the arrival of the train the next day. At daybreak, the commandoes discover that the water level of the river has dropped, exposing the wires leading to the detonator. When the troops march onto the bridge for the ribbon cutting ceremony, Clipton informs Nicholson he wants no part of the festivities and retreats to a hill to watch. As the train whistle is heard in the distance, Nicholson spots the wires and calls Saito to go with him and investigate. Warden watches in disbelief as Nicholson follows the wire to the detonator, incredulous that a British officer would try to prevent an act of sabotage against the enemy. Sneaking up behind Saito, Joyce stabs him in the back with his knife, then informs Nicholson that they have been sent by the British to blow up the bridge. Crazed, Nicholson attacks Joyce, prompting Shears to scream "kill him" and swim to Joyce's defense. As Warden bombards the bridge with mortar shells, the Japanese open fire, wounding Shears and killing Joyce. When the injured Shears dies at Nicholson's feet, the colonel realizes his folly just as he is wounded by mortar fire and falls onto the detonator, setting off the explosives as the train approaches the bridge. As the bridge collapses, sending the train spilling into the river, Clipton surveys the scene and utters "madness."

Director

David Lean

Cast

William Holden

Alec Guinness

Jack Hawkins

Sessue Hayakawa

James Donald

Geoffrey Horne

Andre Morell

Peter Williams

John Boxer

Percy Herbert

Harold Goodwin

Ann Sears

Henry Okawa

Keiichiro Katsumoto

M. R. B. Chakrabandhu

Vilaiwan Seeboonreaung

Ngamta Suphaphongs

Javanart Punynchoti

Kannikar Dowklee

Crew

Gus Agosti

John Apperson

Malcolm Arnold

Donald M. Ashton

Pamela Bosworth

Pierre Boulle

Eric Boyd-perkins

Fred Burnley

Rusty Coppleman

John Cox

Archie Dansie

Teddy Darvas

Janet Davidson

Geoffrey Drake

Peter Dukelow

Cecil F. Ford

Carl Foreman

Stuart Freeborn

Norma Hawkes

Jack Hildyard

Grady Johnson

John Kerrison

Angela Martelli

Peter Miller

John Mitchell

Peter Newbrook

George Partleton

Major-gen. L. E. M. Perowne C.b., C.b.e.

Lt. F. J. Ricketts

Winston Ryder

Sam Spiegel

Ted Sturgis

Peter Taylor

Michael Wilson

Photo Collections

Videos

Movie Clip

Hosted Intro

Film Details

Technical Specs

Award Wins

Best Actor

Best Cinematography

Best Director

Best Editing

Best Picture

Best Score

Best Writing, Screenplay

Award Nominations

Best Supporting Actor

Articles

The Essentials - The Bridge on the River Kwai

* Airs on Sunday, August 31 at 6 pm (ET)

SYNOPSIS

A group of British POWs in Southeast Asia during World War II are forced to build a bridge crucial to the Japanese war plan to link Singapore and Rangoon by railroad, unaware of an Allied mission to destroy it. Concerned first and foremost with military rules and honor, Colonel Nicholson uses the bridge-building as a way to restore morale and order among his troops and show the Japanese the superiority of British know-how, but he soon develops an obsessive pride and protectiveness toward the bridge.

Director: David Lean

Producer: Sam Spiegel

Screenplay: Michael Wilson, Carl Foreman, based on the novel by Pierre Boulle

Cinematography: Jack Hildyard

Editing: George Hively, Peter Taylor

Art Direction: Donald M. Ashton

Music: Malcolm Arnold

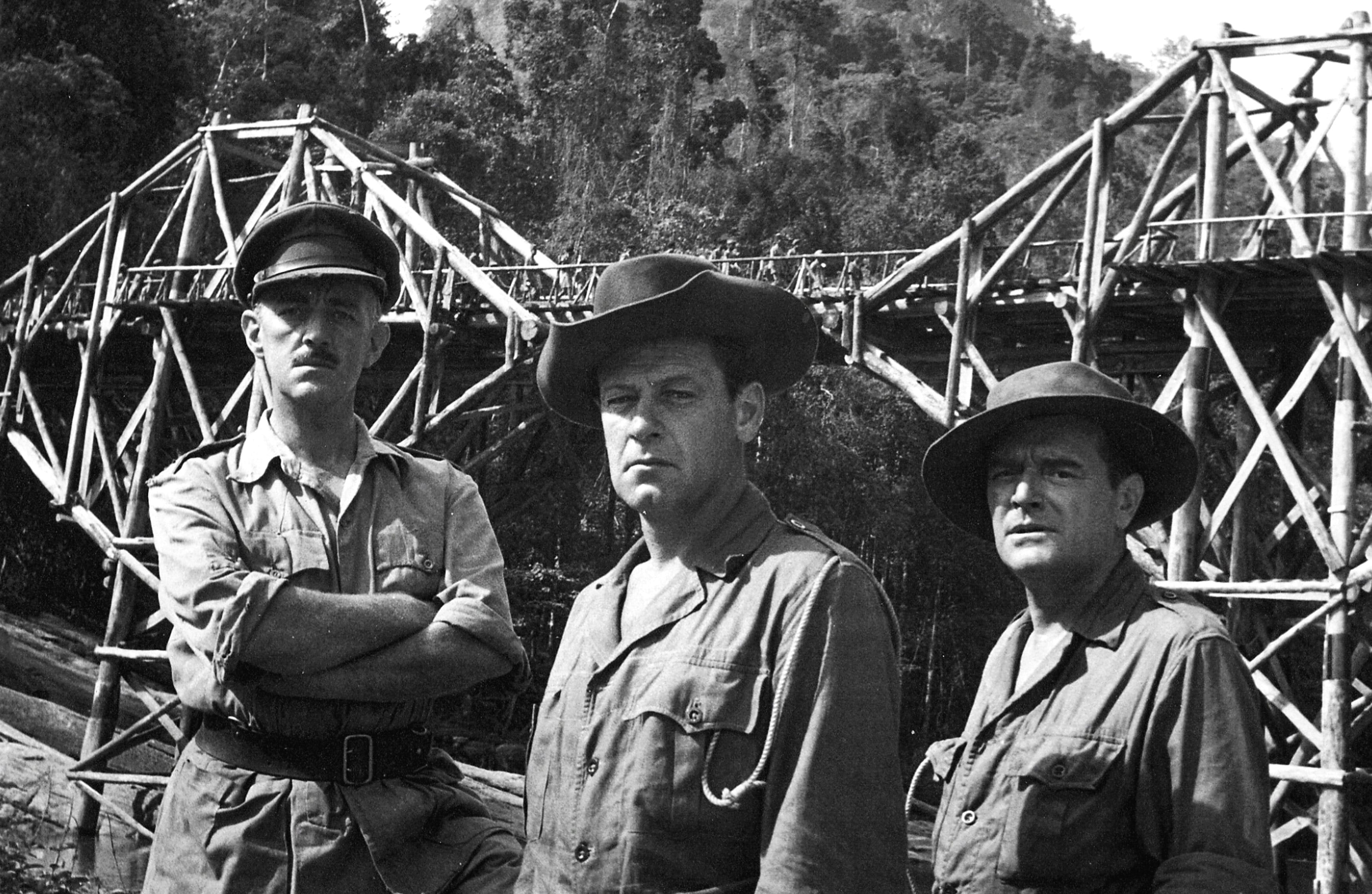

Cast: Alec Guinness (Colonel Nicholson), William Holden (Shears), Jack Hawkins (Major Warden), Sessue Hayakawa (Colonel Saito), James Donald (Major Clipton), Geoffrey Horne (Lt. Joyce).

C-163m. Letterboxed.

Why THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI is Essential

At the time of its release, some critics complained that The Bridge on the River Kwai was confusing: was it for or against war? That ambiguity, however, may be exactly what has contributed to the movie's lasting appeal. In its often uneasy mix of heroism and blind obedience to military honor, large-scale action and subtle characterization, humor and horror, this war movie - one of the biggest and most spectacular ¿turns out to be rather anti-war, while ironically retaining all the crowd-pleasing aspects of a rousing adventure film. As director David Lean himself said, "There has been a lot of argument about the film's attitude toward war. I think it is a painfully eloquent statement on the general folly and waste of war."

Lean's intention was to make a big movie with meaning, an epic with a message. Whether he achieved that has been open to much debate, but it unquestionably made him a major international director. He never made a "small" movie again. The success of The Bridge on the River Kwai also marked a transition for the British film industry. In the years just prior to this picture, the country's film output was characterized by the gentle but biting satires of everyday English life turned out primarily by the Ealing Studios. After this, British releases were dominated by grand epics financed largely by Hollywood studios, many of them directed by Lean himself: Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Doctor Zhivago (1965), Ryan¿ Daughter (1970), A Passage to India (1984). Whether that change was welcome or not is a matter of opinion, but it is a fact that The Bridge on the River Kwai had as profound an influence on the way British films were made and marketed as the American blockbusters of the mid-70s, such as Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977), had on this country's industry.

The Bridge on the River Kwai also brought Alec Guinness to international stardom. Although he was not the first actor considered for the role of Colonel Nicholson, Guinness proved to be an inspired choice. Something seemed to carry over from his days in the Ealing comedies portraying the foibles of the British national character. Here it is pushed to its extreme in his performance as a military officer so caught up in his pride and sense of superiority that he ends up abetting his enemy.

by Rob Nixon

The Essentials - The Bridge on the River Kwai

The Bridge on the River Kwai - The Bridge on the River Kwai

At the time of its release, some critics complained that The Bridge on the River Kwai was confusing: was it for or against war? That ambiguity, however, may be exactly what has contributed to the movie's lasting appeal. In its often uneasy mix of heroism and blind obedience to military honor, large-scale action and subtle characterization, humor and horror, this war movie - one of the biggest and most spectacular - turns out to be rather anti-war, while ironically retaining all the crowd-pleasing aspects of a rousing adventure film. As director David Lean himself said, "There has been a lot of argument about the film's attitude toward war. I think it is a painfully eloquent statement on the general folly and waste of war."

Lean's intention was to make a big movie with meaning, an epic with a message. Whether he achieved that has been open to much debate, but it unquestionably made him a major international director. He never made a "small" movie again. The success of The Bridge on the River Kwai also marked a transition for the British film industry. In the years just prior to this picture, the country's film output was characterized by the gentle but biting satires of everyday English life turned out primarily by the Ealing Studios. After this, British releases were dominated by grand epics financed largely by Hollywood studios, many of them directed by Lean himself: Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Doctor Zhivago (1965), Ryan's Daughter (1970), A Passage to India (1984). Whether that change was welcome or not is a matter of opinion, but it is a fact that The Bridge on the River Kwai had as profound an influence on the way British films were made and marketed as the American blockbusters of the mid-70s, such as Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977), had on this country's industry.

The Bridge on the River Kwai also brought Alec Guinness to international stardom. Although he was not the first actor considered for the role of Colonel Nicholson, Guinness proved to be an inspired choice. Something seemed to carry over from his days in the Ealing comedies portraying the foibles of the British national character. Here it is pushed to its extreme in his performance as a military officer so caught up in his pride and sense of superiority that he ends up abetting his enemy.

The story was also loosely based on a real-life person, Lieutenant Colonel Philip Toosey. Captured in late 1942, Toosey and his men labored through May 1943 under orders to build two Kwai River bridges in Burma (one of steel, one of wood) to help move Japanese supplies and troops from Bangkok to Rangoon. Unlike the fictional plot, the bridges were actually used for two years until they were destroyed in late June 1945.

The Bridge on the River Kwai won Academy Awards® for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (Alec Guinness), Best Adapted Screenplay (Pierre Boulle, Michael Wilson, Carl Foreman), Best Cinematography (Jack Hildyard), Best Editing (Peter Taylor), and Best Score (Malcolm Arnold). It also earned an Academy Award® nomination for Best Supporting Actor (Sessue Hayakawa). In its list of the 100 greatest British films of all time, released in 1999, the British Film Institute ranked The Bridge on the River Kwai number 11. Lean was chosen the greatest British director of all time.

Director: David Lean

Producer: Sam Spiegel

Screenplay: Michael Wilson, Carl Foreman, based on the novel by Pierre Boulle

Cinematography: Jack Hildyard

Editing: George Hively, Peter Taylor

Art Direction: Donald M. Ashton

Music: Malcolm Arnold

Cast: Alec Guinness (Colonel Nicholson), William Holden (Shears), Jack Hawkins (Major Warden), Sessue Hayakawa (Colonel Saito), James Donald (Major Clipton), Geoffrey Horne (Lt. Joyce).

C-163m. Letterboxed. Closed Captioning.

by Rob Nixon

The Bridge on the River Kwai - The Bridge on the River Kwai

Quotes

Do not speak to me of rules. This is war! This is not a game of cricket!- Colonel Saito

You give me powders, pills, baths, injections, enemas; when all I need is love.- Major Shears

You make me sick with your heroics. There's a stench of death about you. You carry it in your pack like the plague. Explosives and L-pills -- they go well together, don't they? And with you it's just one thing or the other: destroy a bridge or destroy yourself. This is just a game, this war! You and Colonel Nicholson, you're two of a kind, crazy with courage. For what? How to die like a gentleman... how to die by the rules... when the only important thing is how to live like a human being.- Major Shears

One day the war will be over. And I hope that the people that use this bridge in years to come will remember how it was built and who built it. Not a gang of slaves, but soldiers, British soldiers, Clipton, even in captivity.- Colonel Nicholson

Be happy in your work.- Colonel Saito

Trivia

Cary Grant was originally slated to star but he withdrew due to other commitments and was replaced by 'Holden, William' .

Howard Hawks was asked to direct, but declined. After the box-office failure of Land of the Pharaohs (1955), he didn't want a second one in a row, and he thought the critics would love this movie but the public would stay away. One particular concern was the all-male lead roles.

Michael Wilson (I) and Carl Foreman were on the blacklist of people with suspected Communist ties at the time the movie, and went uncredited. The sole writing credit, and so the Oscar for best adapted screenplay, went to Pierre Boulle, who wrote the original French novel but did not even speak English.

In 1984 the Academy retrospectively awarded the Oscar to Wilson and Foreman. Wilson did not live to see this; Foreman died the day after it was announced. When the film was restored, their names were added to the credits.

While the bridge in the story was constructed by prisoners in two months, the actual one built in Ceylon by a British company for the filming (425 feet long and 50 feet above the water) took eight months, with the use of 500 workers and 35 elephants. It was demolished in a matter of seconds, and the total cost was 85,000 pounds.

Notes

The working title of the film was The Bridge Over the River Kwai, which was the English translation of the title of Pierre Boulle's novel. The opening and closing cast credits differ slightly in order. In the opening credits, Geoffrey Horne's name is proceeded by the phrase "and introducing." However, Horne had previously appeared in the 1957 film The Strange One (see below). In the onscreen credits, the credit for chief sound editor is followed by the word "with" and a list of all the sound editors. The film closes with the following written acknowledgment: "The producers gratefully acknowledge the co-operation and help extended to them by the various departments of the government of Ceylon during the course of the production of this film." The film was shot entirely on location in Sri Lanka, which was then known as Ceylon. The film's signature tune, "Colonel Bogey March," which is whistled by "Nicholson" and his troops at the film's opening, became an immensely popular hit and an iconographic musical theme.

The action in the film roughly parallels that of the Boulle novel on which it was based. One major difference, however, is that in the novel, the character of "Shears" is British, not American. The novel features an epilogue in which "Warden" returns to the commando school and reports that the damaged bridge was still intact and that "Joyce" and Shears, injured by enemy fire, were killed by mortar fire delivered by Warden in order to save them from Japanese capture. Boulle's book was inspired by the stretch of railway from Thailand to Burma (now Myanmar) known as "The Death Railway." The corridor was built by the Axis powers during World War II to transport Japanese troops and supplies to Burma. Approximately 100,000 conscripted Asian laborers and 16,000 Allied prisoners of war died while working on the project. The construction of the railway became necessary when Allied troops mined the sea route through the Strait of Malacca, the main route by which Japanese support troops were transported to Burma.

The project was started in June 1942. The wooden bridge over the River Kwae Yai, which in Boulle's book was called the River Kwai, was completed in February 1943, followed by a concrete and steel bridge completed in June 1943. Both bridges were destroyed by Allied bombers on 2 April 1945, although they had been damaged and repaired several times before. Although as many of the film reviews noted, the film's Japanese prison camp was in Burma, while the actual bridge over the Kwae Yai River is in Thailand.

In 1943, Boulle himself was captured by Vichy French loyalists on the Mekong River and sentenced to a life of hard labor at a prison camp in Saigon. After escaping in 1944, Boulle served with British Special Forces until the end of the war. Although several newspaper articles, including an October 1997 article in The Observer (London), noted similarities between "Col. Nicholson" and the real-life Lt. Col. Philip Toosey, a British officer serving in Singapore who was captured by the Japanese in 1942 and forced to help build the bridge, Boulle claimed that he based Nicholson on two officers he had known in Indochina. Unlike Nicholson, Toosey was not an upper-class career officer, but a Territorial Army Officer.

^Although modern sources have mentioned several actors that were considered for the parts of Nicholson and Shears, IHR news items have substantiated the following information about the production: In April 1956, it was announced that Charles Laughton was to appear as Nicholson. Although a November 1956 news item announced that Brenda Marshall was cast in a featured role opposite her then real-life husband, William Holden, Marshall does not appear in the film. A December 1956 news item announced that 2d assistant director John Kerrison was killed on 2 December in an auto accident. According to studio publicity contained in the film's production file at the AMPAS Library, location filming was done at the Kelani River in Sri Lanka. A November 1956 news item described the 400-foot wooden bridge that was constructed for the production. The bridge, which was as tall as a six-story building, required the labor of twenty-five elephants and hundreds of native workers, and took six months to complete, according to studio publicity.

Studio publicity also noted that the train in the film was a sixty-year-old locomotive that once served an Indian maharajah. Producer Sam Spiegel bought the train from the Ceylonese government so that he could blow it up. The paratroopers in the film were members of the RAF stationed in Sri Lanka, according to studio publicity. A December 1956 news item explained that in order to film the paratroopers jumping from their plane, director of photography Jack Hildyard lashed himself to the wing of the British military plane carrying the paratroopers and shot the jump with a handheld 16mm camera. A January 1957 news item noted that actor Percy Herbert, who played the role of a prisoner of war in the film, actually spent four years as a Japanese prisoner of war in Singapore. Although an April 1957 Hollywood Reporter production chart places Pom Prom in the cast, Prom's appearance in the released film has not been confirmed. According to a February 1958 Hollywood Reporter news item actor William Holden received ten percent of the film's gross, which, according to modern sources, made him the highest paid film star at the time and represented a ground-breaking financial agreement.

The Variety review noted that author Boulle, who spoke no English, did an "excellent job of screenwriting, (particularly because it marked [his] debut in the medium)." In reality, the screenplay was written by blacklisted writers Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson. They were posthumously awarded an Academy Award for Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium in 1985, and their screenwriting credit was restored by the WGA in 2000. The question of the screenplay's authorship was addressed several times in Hollywood Reporter columns in 1957 and 1958. Although Foreman and Wilson received no screen credit, a January 17, 1957 "Rambling Reporter" news item noted that Foreman wrote the screenplay and owned a "big chunk" of the production. This assertion was immediately denied by Spiegel in a January 21, 1957 Hollywood Reporter news item. In a February 1958 "Broadway Ballyhoo" column, Holden called the reports about Foreman writing the screenplay "hogwash." According to a February 1958 "Rambling Reporter" item, when Boulle was presented the British Film Academy's award for Best Screenplay, he announced that he did not write the screenplay. Spiegel then clarified that the screenplay was written by several people, among them director David Lean, Boulle and Spiegel himself, who decided to credit only Boulle onscreen.

According to a modern source, Foreman optioned Boulle's novel, hoping that Zoltan Korda would direct it. When Zoltan's brother Alexander criticized the script as being anti-British, Foreman formed a partnership with Spiegel and Korda left the project. Lean reportedly hated Foreman's original version of the screenplay and asked producer Norman Spencer, who worked with the director on the 1955 film Summertime (see below) to help write a new treatment. Foreman then rewrote the script, but Spiegel was unhappy with the finished product and asked writer Calder Willingham to work on script revisions. Although an August 1956 Hollywood Reporter news item confirmed that Willingham was working on script revisions, the modern source notes that Lean was unhappy with his work and Wilson was then brought in to work with Lean on the script. The extent of Willingham's contribution to the final script, if any, has not been determined.

Modern sources add the following production credits: Eddie Fowlie (Prop master); Keith Best (Const eng); Gerry Fisher (Camera Operator); Tommy Early (Props); Frankie Howard (Stunts); Tommy Nichol (Assistant Camera); Freddy Ford (2d unit cam); and Fred Lane (Carpenter). According to a December 1958 Hollywood Reporter news item, Red Skelton and Sessue Hayakawa were to appear in feature-length satire of The Bridge on the River Kwai entitled The Tunnel of Kwai, which would be filmed in Japan and "scheduled for release only to the Orient with Japanese dialogue." However, no additional information on the film has been located.

In addition to the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, The Bridge on the River Kwai won the following Academy Awards: Alec Guinness, Best Actor; Jack Hildyard, Best Cinematography; David Lean, Best Director; Peter Taylor, Best Film Editing; Malcolm Arnold, Best Music Scoring and producer Sam Spiegel for Best Picture. Sessue Hayakawa was nominated for Best Supporting Actor. The film also won a Golden Globe for Best Picture-Drama, Best Motion Picture Actor in a Drama (Guinness) and Best Director. Among other honors garnered by the film was the DGA Award for Best Director, the National Board of Review for Best Actor (Guinness), Best Director, Best Picture and Best Supporting Actor (Hayakawa) and the New York Film Critics Award for Best Actor (Guinness), Best Director and Best Film.

Miscellaneous Notes

Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, both blacklisted writers at the time of the film's original release, were officially recognized by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, which presented their widows with posthumous Oscars for Best Screenplay in 1984.

Voted Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor (Guinness) of the Year by the 1957 New York Film Critics Association.

Voted Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor (Guiness), and Best Supporting Actor (Hayakawa) of the Year by the 1957 National Board of Review.

Voted One of the Year's Ten Best Films by the 1957 New York Times Film Critics.

Released in United States Winter December 1957

Re-released in United States on Video February 13, 1996

Re-released in United States on Video November 7, 2000

Selected in 1997 for inclusion in the Library of Congress' National Film Registry.

CinemaScope

Shot from October 1956 to May 1957.

Re-released in United States on Video February 13, 1996 (David Lean Box Set "The Bridge on the River Kwai" & "Lawrence of Arabia")

Re-released in United States on Video November 7, 2000

Released in United States Winter December 1957