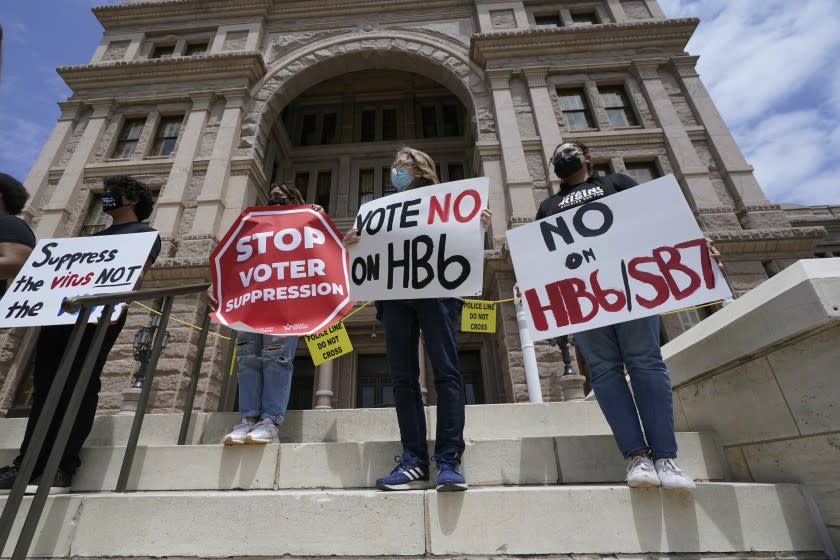

Texas Republicans' push to restrict voting is straining their close ties with business

Texas Republicans doggedly courted corporate America for decades, an approach personified by former Gov. Rick Perry, who took to radio airwaves in California to urge businesses to “come check out Texas.”

When it comes to voting restriction bills now being considered in the Texas Statehouse, however, GOP lawmakers have broadcast a different message to the business community: Back off.

Be it Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick berating American Airlines for opposing the legislation or lawmakers floating proposals to punish companies for speaking out, the effort to tighten Texas’ already strict voting rules has spurred unusual acrimony between the majority party and corporations, its usual allies.

Democrats and civil rights advocates, meanwhile, contend that businesses have not done enough to flex their considerable influence in the statehouse against the measures.

The corporate response had been somewhat muted as the bills advanced through the statehouse. But this week, coalitions of businesses and executives made an 11th-hour push against the legislation, which is among the hundreds of election bills championed by Republicans nationwide in response to former President Trump’s false allegations of widespread fraud in last year’s presidential contest.

The measures have changed substantially as they’ve advanced through the Texas Legislature. A pared-back version passed the state House on Friday; it would, among other things, make it a crime for county election officials to proactively send out vote-by-mail applications.

Even with the changes, Democrats remained opposed to the bill, arguing that such policies were unnecessary given the lack of documented fraud in last year’s election.

Activist groups warned that more onerous provisions could be reinserted during final negotiations before the bill reaches the governor’s desk.

American Airlines and Dell were among the first Texas companies to stake out opposition to the measures, immediately after Georgia passed its own voting restrictions in March.

“When Georgia happened, there was a proliferation of companies trying to jump on the woke bandwagon,” said David Carney, a GOP strategist and advisor to Texas Gov. Greg Abbott.

But, Carney said, Democrats harmed their cause by overstating the effects of the Georgia bill, including President Biden misrepresenting how it affected voting hours. He said Texas Republicans were able to avoid a full-blown business uprising in their state with the message: “Read the bill.”

In defending the legislation, GOP officials have been decidedly hostile. In an animated news conference last month, Patrick mockingly addressed “Mr. American Airlines” and said he took the airline’s opposition personally.

“When you suggest that we’re trying to suppress the vote, you’re in essence between the lines calling us racist, and that will not stand,” he said.

Later, Republicans introduced three budget amendments that would penalize companies who opposed election bills or threatened adverse actions such as a boycott in response to proposals by state politicians. All were ultimately withdrawn.

In a op-ed last week about the corporate response to Georgia’s voting law, Texas Sen. Ted Cruz fumed that “for too long, woke CEOs have been fair-weather friends of the Republican Party” and vowed to stop taking contributions from their political action committees.

Glenn Hamer, president of the statewide Texas Assn. of Business, was sanguine in asserting that such rhetoric would not amount to an about-face on the state’s pro-business policy tilt.

“You’re not going to see anything pass that is punitive to the business community,” said Hamer, whose group has not taken a stance on the voting legislation.

But political observers say the GOP’s stinging language is a sign of a fraying political partnership.

“It’s like a reactive response where [Republicans’] allies have betrayed them and so they’re lashing out against them,” said Kenneth Miller, author of “Texas vs. California: A History of Their Struggle for the Future of America.”

The GOP as a whole has been shifting more toward populism in recent years. Nowhere is that evolution more stark than in the Lone Star State, where the party once staked its brand on the “Texas Miracle” and attributed the state’s booming growth to its low-tax, low-regulation approach.

Three successive GOP governors — George W. Bush, Perry and Abbott — were especially vigorous in wooing companies. By the early 2000s, “the phrase ‘business-friendly Texas Republican Party’ was all you heard,” said Cal Jillson, political science professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

These days, however, “you would describe the Texas Republican Party as social issues first, businesses second,” Jillson said.

State Rep. Rafael Anchía, a Democrat from Dallas, said that has left businesses “frustrated by all these culture wars that have been waged to appease an increasingly rabid base.”

Meanwhile, the corporate community has been undergoing its own evolution — prodded by consumers and their own workforce — to be more outspoken on social issues, such as LGBTQ rights and racial equality.

Tensions rose in 2017 when social conservatives including Patrick rallied around a “bathroom bill,” which would have required transgender people to use facilities based on their biological sex, not gender identity. A similar measure in North Carolina in 2016 set off a cascade of boycotts among businesses and sports leagues before the state repealed the law.

Texas companies feared their state would take a similar hit and worked with then-House Speaker Joe Straus, a Republican, to block the measure, much to the ire of conservative activists.

Now, the top priority for party die-hards are these voting measures, which reinforce Trump’s false narrative of election high jinks.

“If you’re on the wrong side of Donald Trump, you’re going to lose your primary and lose your seat,” said Jason Villalba, who served as a Dallas-area Republican in the state House and was defeated by a conservative in the 2018 primary. “There’s no other explanation why a bill like this gets this far.”

The business world has hardly been uniform in response to the legislation.

“Some companies have been quite outspoken,” said state Rep. Chris Turner, a Democrat from Grand Prairie. “However, I’d like to see more businesses speak out. This affects their employees, affects their customers, affects the social fabric of our state.”

The powerful Greater Houston Partnership, a business association, opted not to take a position on the voting legislation, citing “no consensus” on the board.

That garnered a swift rebuke from Lina Hidalgo, chief executive of Harris County, and Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner, who said Wednesday they would boycott speeches to the group.

“Voting rights are falling like dominoes in states across the country from Georgia to Arizona to right here in Texas. Yet the largest chamber of commerce is silent,” Hidalgo said, noting that the group vowed after the killing of George Floyd to stand up for civil rights. “We do not feel confident elevating them after seeing them shrink from the civil rights struggle of our time.”

Some on the partnership’s board organized their own missive, released Tuesday, that pointedly denounced the bills. A separate letter organized by Fair Elections Texas came out the same day, calling on election officials to oppose any changes to law that would hamper voting. Its signatories included a mix of national brands such as Patagonia, Unilever and HP, as well as homegrown entrepreneurs.

“For us, it was personal,” said Todd Coerver, chief executive of P. Terry’s, an Austin-based burger chain. “We represent a workforce of about 925 folks — primarily hourly, minority employees. Often, these folks are the most challenged when it comes to voter access.”

Others point to fears of lost business due to boycotts or companies deciding not to expand in the state.

The decision of Major League Baseball to move the All-Star game from Georgia after the state passed voting restrictions looms large in Texas, which is scheduled to host two NCAA Final Four tournaments within the next four years and is in the running for the 2026 FIFA World Cup, which will be hosted in cities across the U.S., Mexico and Canada. A Waco economist estimated fallout to tourism and economic development from the voting bills could cost the state nearly $17 billion and about 150,000 jobs by 2025.

Nathan Ryan, chief executive of the Austin-based business consulting firm Blue Sky Partners, said Republicans, by increasingly focusing on wedge issues to rally their base, risk keeping out the companies they so assiduously pursued.

“It is the height of ‘cancel culture,’” Ryan said, emphasizing air quotes to denote his skepticism over the term that has become a conservative rallying cry, “to produce policy changes that would hurt corporations that are taking a stand.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.