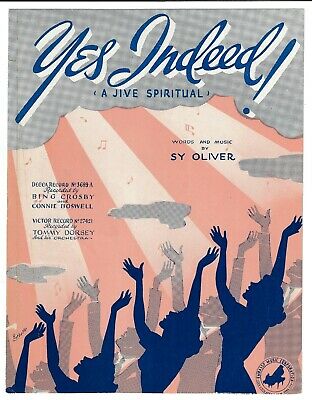

“Yes Indeed!”

Composed and arranged by Sy Oliver.

Recorded by Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra for Victor on February 17, 1941 in New York.

Tommy Dorsey, first and solo trombone, directing: Ziggy Elman, first trumpet; Ray Linn, Jimmy Blake, Chuck Peterson trumpets; George Arus, Les Jenkins and Lowell Martin, trombones; Freddie Stulce, first alto saxophone; Johnny Mince, alto saxophone; Don Lodice and Paul Mason, tenor saxophones; Heinie Beau, baritone saxophone; Joe Bushkin, piano; Clark Yocum, guitar; Sid Weiss, bass; Buddy Rich, drums; Sy Oliver and Jo Stafford, vocals.

The story:

Tommy Dorsey was not just a virtuoso trombonist, and a pioneer in moving forward how the instrument could be played. He was not just a superb bandleader who had the ability to elicit great performances from his various orchestras. He was as Bud Freeman, one of his most talented sidemen, told me “an operator,” meaning that he was always involved in cooking up some scheme that would advance his band’s popularity. He was not only a public relations person’s dream, he was always his own best public relations person. He loved radio and relished reading scripted lines on radio, and he did that and also ad-libbed very well. He had a great sense of humor, true wit and good comedy timing. He could make people laugh, and he loved to laugh himself. Through his long experience in show business, starting in the 1920s and running into the mid-1950s, he had met and become friends with countless performers, including musicians, other bandleaders and singers. (Above left – Tommy Dorsey in 1938.) After he had befriended someone, he would not hesitate to try to include them, if they could help him, in whatever public relations gimmick he was working on at any given moment.

Tommy Dorsey was not just a virtuoso trombonist, and a pioneer in moving forward how the instrument could be played. He was not just a superb bandleader who had the ability to elicit great performances from his various orchestras. He was as Bud Freeman, one of his most talented sidemen, told me “an operator,” meaning that he was always involved in cooking up some scheme that would advance his band’s popularity. He was not only a public relations person’s dream, he was always his own best public relations person. He loved radio and relished reading scripted lines on radio, and he did that and also ad-libbed very well. He had a great sense of humor, true wit and good comedy timing. He could make people laugh, and he loved to laugh himself. Through his long experience in show business, starting in the 1920s and running into the mid-1950s, he had met and become friends with countless performers, including musicians, other bandleaders and singers. (Above left – Tommy Dorsey in 1938.) After he had befriended someone, he would not hesitate to try to include them, if they could help him, in whatever public relations gimmick he was working on at any given moment.

By 1941, Tommy Dorsey had been performing for audiences for some twenty years, first as a sidemen, later (starting in 1934) as the leader of his own band. He gradually learned what his audiences liked and wanted. (His star clarinetist from 1937 to 1941, Johnny Mince, once told me: “Tommy had an applause meter in his head.”) That applause meter guided TD’s selection of music. He constantly tried to give audiences what they wanted. Consequently, Tommy Dorsey was one of the most consistently popular bandleaders from the mid-1930s until the mid-1950s.

As a show business “operator,” Tommy knew where the action was, and always wanted to be, indeed had to be, in the thick of it. He also understood what it took to keep his band successful as a business enterprise, in addition to giving his audiences what they wanted musically. When Benny Goodman was signed to appear weekly on the sponsored CBS radio network Camel Caravan radio show in mid-1936, Tommy understood immediately that that would raise the public awareness of BG’s band and music, and at the same time, provide Benny with an ongoing source of revenue which would ensure that he could keep his band personnel as stable and strong as possible. Tommy, then both personally and through his various agents and business associates, began to lay siege to the offices of his (and Goodman’s) booking agent, Music Corporation of America (MCA), located in the Squibb Building on Fifth Avenue (1) in Manhattan, demanding that they get him his own radio show.

As a show business “operator,” Tommy knew where the action was, and always wanted to be, indeed had to be, in the thick of it. He also understood what it took to keep his band successful as a business enterprise, in addition to giving his audiences what they wanted musically. When Benny Goodman was signed to appear weekly on the sponsored CBS radio network Camel Caravan radio show in mid-1936, Tommy understood immediately that that would raise the public awareness of BG’s band and music, and at the same time, provide Benny with an ongoing source of revenue which would ensure that he could keep his band personnel as stable and strong as possible. Tommy, then both personally and through his various agents and business associates, began to lay siege to the offices of his (and Goodman’s) booking agent, Music Corporation of America (MCA), located in the Squibb Building on Fifth Avenue (1) in Manhattan, demanding that they get him his own radio show.

By November of 1936, MCA did in fact get him his own sponsored network radio show, albeit one where he was presented initially as a supporting act for the headliner, comedian Jack Pearl. (Pearl was eased out of the show by mid-1937, after which Tommy had it to himself.) This show, sponsored by Raleigh and Kool cigarettes, on which TD would continue appearing weekly through 1939, provided for him the same ongoing widespread public exposure and cash-flow as the Camel Caravan provided for Benny Goodman during the same time period. By 1939, both Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey were household names in the US, and wealthy men.

Tommy Dorsey and his band pose for a publicity photo in NBC studio 8G before a broadcast of Tommy’s Raleigh-Kool radio show – probably November of 1937. L-R back: Lee Castle (Aniello Castaldo), Andy Ferretti, George “Pee Wee” Erwin, Maurice (Moe) Purtill (2), Carmen Mastren, Gene Traxler, Howard Smith; front: Edythe Wright, Jack Leonard, Axel Stordahl, Les Jenkins, Earle Hagen, TD, Johnny Mince, Arthur “Skeets” Herfurt, Freddie Stulce, Lawrence “Bud” Freeman, Paul Stewart, Dwight Weist, and John Holbrook.

Tommy worked within pretty much the same musical format during the time he was featured on the Raleigh-Kool radio show. Although he always strove to present as wide a spectrum of music as possible, including some worthwhile jazz, given the limits and conventions of late 1930s network radio, the musical fare he served up most of the time was middle-of-the-road dance music, with lots of vocals by Edythe Wright and Jack Leonard, both of whom audiences liked.  (At left: TD and Edythe Wright – 1938.) However, Tommy, like any bandleader being presented on a high-level sponsored network radio show, had to work with and please not only the audiences that showed up in the broadcast studio, and the network radio audience, but the sponsor of the show, and its advertising agency. The sponsor of the show, the Brown and Williamson Tobacco Co. contracted with a New York advertising agency, Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn, and the agency provided the creative know-how to produce the shows. The liaison from B,B,D and O who worked with Tommy to put each show together was a young man named Herb Sanford. (3) Occasionally, the de facto producers of the show, Tommy and Sanford, came up with ideas for a special show. One such idea was ultimately called Evolution of Swing, which was intended to devote a show to taking a retrospective look at where swing came from musically. This show aired on January 14, 1938. (By some strange coincidence, Benny Goodman presented a similar retrospective on the stage of Carnegie Hall two days later.)

(At left: TD and Edythe Wright – 1938.) However, Tommy, like any bandleader being presented on a high-level sponsored network radio show, had to work with and please not only the audiences that showed up in the broadcast studio, and the network radio audience, but the sponsor of the show, and its advertising agency. The sponsor of the show, the Brown and Williamson Tobacco Co. contracted with a New York advertising agency, Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn, and the agency provided the creative know-how to produce the shows. The liaison from B,B,D and O who worked with Tommy to put each show together was a young man named Herb Sanford. (3) Occasionally, the de facto producers of the show, Tommy and Sanford, came up with ideas for a special show. One such idea was ultimately called Evolution of Swing, which was intended to devote a show to taking a retrospective look at where swing came from musically. This show aired on January 14, 1938. (By some strange coincidence, Benny Goodman presented a similar retrospective on the stage of Carnegie Hall two days later.)

The Evolution of Swing show was very well received by Tommy’s radio audience. It was so well received that his sponsor and ad agency made it known that they wanted a follow-up. The eventual result was an ongoing feature, the Tommy Dorsey Amateur Swing Contest. Here is how that worked: “In a ten-minute segment, we introduced four young instrumentalists, selected from auditions held the previous week. Each player, after a few get-acquainted words, played a tune of his/her choice. Studio audience reaction, registered on an applause meter, determined the winner, who received a $75 prize and a chance to swing with Tommy and his band.” (4) The Amateur Swing Contest was, according to Sanford, “enormously successful.”

Tommy’s success on his radio show triggered another siege of MCA’s Fifth Avenue office by TD and his phalanx of managers, assistants and others in his employ. Now Tommy wanted to be featured in a Hollywood feature film, as Benny Goodman had been in both 1936 and 1937. Meetings were held, discussions were had. Tommy got no movie deal. He was enraged. (This may have been the time when, according to Bud Freeman, Tommy took a fire axe out of a fire emergency cabinet in the hallway outside of Jules Stein’s office, then went into Stein’s office with it in hand and threatened to reduce his desk to fire wood. Stein was president of MCA.) Apparently, Tommy was mollified by being promised a lucrative cross-country road tour, which would end up in Los Angeles.(Above right: An angry looking Tommy Dorsey in the late 1930s when he was featured on the Raleigh-Kool radio show on NBC. TD was serious about music making, business, and advancing his career. Most everything else was subject to negotiation.)

The tour was a success, and the Amateur Swing Contest worked very well in various cities from which Tommy’s radio show was broadcast as the band worked its way west. Tommy and Sanford then hatched the idea of presenting the final Swing Contest in Hollywood, using film personalities as the “amateur” contestants. Sanford had no idea how such a show would be put together. Tommy did, however.

Upon reaching Hollywood, Tommy immediately called Bing Crosby, whom he had known by then for over ten years. They had met and worked together in Paul Whiteman’s orchestra in the late 1920s, and had worked together intermittently since then on radio and records. Crosby’s career had skyrocketed since he left Whiteman. By 1938, he was one of the biggest movie stars in Hollywood, accounting for a vast amount of the revenue generated each year by Paramount Pictures. He was also the biggest star on Decca Records then, selling millions of records each year. Finally, he was the star of his own very popular network radio show, The Kraft Music Hall, on NBC. Bing received Tommy and Sanford warmly at his palatial home located at 10500 Camarillo Street in the Toluca Lake district of North Hollywood. Tommy pitched the idea of the celebrity Amateur Swing Contest to Crosby, who liked it. Bing, who had played drums early in his career, said he would do it.

Others were soon rounded-up largely because Crosby was going to appear. Actor Dick Powell (who had starred in the Benny Goodman film “Hollywood Hotel” the previous year), blew the dust out of the trumpet he had played as a teen-ager. Ken Murray agreed to play clarinet. Actress Shirley Ross was known as a passable pianist. The “contestants” were now set, almost. (At left: Jack Benny and TD, on Tommy’s radio show – 1938.)

Others were soon rounded-up largely because Crosby was going to appear. Actor Dick Powell (who had starred in the Benny Goodman film “Hollywood Hotel” the previous year), blew the dust out of the trumpet he had played as a teen-ager. Ken Murray agreed to play clarinet. Actress Shirley Ross was known as a passable pianist. The “contestants” were now set, almost. (At left: Jack Benny and TD, on Tommy’s radio show – 1938.)

As Tommy and Sanford were having lunch one day at the Melrose Grotto during a break from rehearsal at NBC next door, this tableau, later recalled by Herb Sanford, unfolded: “…Jack Benny came in and sat down with us. ‘I hear you’re having some kind of swing contest. You’re not going to leave me out, are you?’ We were transfixed. This was incredible. He was asking us? If Tommy and I were not entirely coherent in out reply, there could be no doubt that we extended a welcome. Now there were five, and a violin too. (All of this) happened because Bing had met up with Jack Benny while he (Bing) was bicycling around the Paramount lot. He stopped Jack and told him what was going on…Jack’s next stop was our cubicle at the Melrose Grotto.” (5)

Tommy Dorsey’s Amateur Swing Contest, July 20, 1938 at NBC Hollywood. Contestants L-R: Jack Benny, violin; Dick Powell, trumpet; Ken Murray, clarinet; Bing Crosby, drums; Shirley Ross, piano, accompanied by Tommy Dorsey, trombone.

As one would expect, the show was full of hilariously bad music from the contestants, ad-libbed zingers between the contestants and TD that were very funny, and an air of joviality and good-natured fun. (When TD asked Jack Benny what he did for a living, Benny said laconically: “I’m in pictures.” Then, after the perfect pause, Benny followed up by saying: “I’m a lover.” It took about ten seconds for the audience to stop laughing.) The show was also a ratings block-buster.

Tommy Dorsey never forgot what Bing Crosby did to help him. When the broadcast had concluded, he thanked everyone who participated, and especially thanked Crosby, telling him “I owe you one.”

That broadcast also marked the beginning of Tommy Dorsey’s career as a media star. From that point until his death, TD was almost continuously working in some form of mass media – network radio, Hollywood films, and later, network television, in addition of course to making commercial recordings.

Fast-forward to late 1940. Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra are in Hollywood to finally make their first feature film, Las Vegas Nights, for Paramount Pictures. (6) The film, seen today, is rather simplistic and juvenile. Nevertheless, it provided an opportunity for TD to appear in six different numbers onscreen. This alone would ensure massive publicity for the TD band. Tommy would make many more and many better movies in Hollywood as the 1940s progressed.

Also on the Paramount lot at the same time, making The Road to Zanzibar, was Bing Crosby, who headed the cast that included Bob Hope and Dorothy Lamour. Bing, who relieved the tedium of making films by riding a bicycle around the Paramount lot, biked over to the set where Tommy and his band were making Las Vegas Nights. Tommy greeted Bing warmly. At that moment, Sy Oliver also happened to be on the set talking over some new arrangements with TD. Tommy introduced Sy to Bing, who was complimentary of Sy’s work. “The three men spent much of the week (at Paramount) in each other’s company. One day they gathered in Bing’s office to listen to a transcription disk of Victor Young’s arrangement of the song that (would open) ‘The Road to Zanzibar.’ (a tune called) ‘You Lucky People You.’ Bing was to prerecord the tune the next day. ‘Obviously he didn’t like the arrangement’ recalled Sy Oliver, ‘but before I could stop Tommy, he said ‘Hey, Sy, why don’t you knock off an arrangement for Bing?’ ‘So I wrote one overnight, and Bing was so pleased that he said he wanted to do something for me in return, like introduce a song of mine on his radio show, the Kraft Music Hall.’ Sy demurred, but Tommy persisted. ‘Come on Sy, you always have something extra in your briefcase.’ (So) Sy pulled out a lead sheet he had written five years earlier for (Jimmie) Lunceford, who had rejected it as being sacrilegious, a faux gospel lampoon of holy roller preachers called ‘Yes Indeed!’ That week, Bing sang (‘Yes Indeed”) as a duet with Connie Boswell on (The Kraft Music Hall).” (7)

Also on the Paramount lot at the same time, making The Road to Zanzibar, was Bing Crosby, who headed the cast that included Bob Hope and Dorothy Lamour. Bing, who relieved the tedium of making films by riding a bicycle around the Paramount lot, biked over to the set where Tommy and his band were making Las Vegas Nights. Tommy greeted Bing warmly. At that moment, Sy Oliver also happened to be on the set talking over some new arrangements with TD. Tommy introduced Sy to Bing, who was complimentary of Sy’s work. “The three men spent much of the week (at Paramount) in each other’s company. One day they gathered in Bing’s office to listen to a transcription disk of Victor Young’s arrangement of the song that (would open) ‘The Road to Zanzibar.’ (a tune called) ‘You Lucky People You.’ Bing was to prerecord the tune the next day. ‘Obviously he didn’t like the arrangement’ recalled Sy Oliver, ‘but before I could stop Tommy, he said ‘Hey, Sy, why don’t you knock off an arrangement for Bing?’ ‘So I wrote one overnight, and Bing was so pleased that he said he wanted to do something for me in return, like introduce a song of mine on his radio show, the Kraft Music Hall.’ Sy demurred, but Tommy persisted. ‘Come on Sy, you always have something extra in your briefcase.’ (So) Sy pulled out a lead sheet he had written five years earlier for (Jimmie) Lunceford, who had rejected it as being sacrilegious, a faux gospel lampoon of holy roller preachers called ‘Yes Indeed!’ That week, Bing sang (‘Yes Indeed”) as a duet with Connie Boswell on (The Kraft Music Hall).” (7)

The music:

Sy Oliver’s composition and arrangement of “Yes Indeed!” is a classic example of his great ability to creatively use simple musical ideas and techniques to achieve brilliantly colorful and memorable music. Of course, the virtuoso performance of Oliver’s music by Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra does it full justice. Oliver starts this classic performance by announcing its title, and then featuring the four trombones, playing quietly into their cup mutes (accompanied only by Sid Weiss’s bass, Clark Yocum’s guitar and Buddy Rich’s high-hat cymbals played with his foot pedal), playing the melody. (There is no introduction.) The first contrast comes when the entire band, dominated by Ziggy Elman’s big-toned lead trumpet, comes in blasting over the rocking rhythm, led by drummer Buddy Rich. In this sequence, the eight man brass team play call and response with the saxophone quintet. The next part of the arrangement has the trumpets, trombones and saxophones sometimes playing separately and antiphonally, which is a contrast from what had been played immediately before. Yet another contrast arrives when the saxophones play alone, without any accompaniment. This leads into some chanting of Yes Indeed! by the band members, over the rhythm and Ziggy Elman’s brief trumpet aside.

Sy Oliver’s composition and arrangement of “Yes Indeed!” is a classic example of his great ability to creatively use simple musical ideas and techniques to achieve brilliantly colorful and memorable music. Of course, the virtuoso performance of Oliver’s music by Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra does it full justice. Oliver starts this classic performance by announcing its title, and then featuring the four trombones, playing quietly into their cup mutes (accompanied only by Sid Weiss’s bass, Clark Yocum’s guitar and Buddy Rich’s high-hat cymbals played with his foot pedal), playing the melody. (There is no introduction.) The first contrast comes when the entire band, dominated by Ziggy Elman’s big-toned lead trumpet, comes in blasting over the rocking rhythm, led by drummer Buddy Rich. In this sequence, the eight man brass team play call and response with the saxophone quintet. The next part of the arrangement has the trumpets, trombones and saxophones sometimes playing separately and antiphonally, which is a contrast from what had been played immediately before. Yet another contrast arrives when the saxophones play alone, without any accompaniment. This leads into some chanting of Yes Indeed! by the band members, over the rhythm and Ziggy Elman’s brief trumpet aside.

Oliver then sings the hip-humorous lyric, being accompanied in this duet by Jo Stafford. This vocal chorus is yet another contrast — Oliver’s masculine voice with Stafford’s feminine voice. Oliver was a trumpeter who sang in his days with Jimmie Lunceford’s band. In Tommy Dorsey’s band, he was an arranger who sang on rare occasions. Ms Stafford came into the TD band as a member of the singing group The Pied Pipers. Tommy soon began featuring her as a soloist largely because she used her voice as a musician would play an instrument. She was one of the most in-tune, on-pitch singers to emerge from the swing era, and she also had excellent voice quality and range. And she swung. Gradually, she became a great favorite with TD audiences, and then went on to a major career as a solo singing artist. (Above left – Jo Stafford pictured in front of a window on an upper floor at the Essex House in NYC – 1940s.)

Oliver then sings the hip-humorous lyric, being accompanied in this duet by Jo Stafford. This vocal chorus is yet another contrast — Oliver’s masculine voice with Stafford’s feminine voice. Oliver was a trumpeter who sang in his days with Jimmie Lunceford’s band. In Tommy Dorsey’s band, he was an arranger who sang on rare occasions. Ms Stafford came into the TD band as a member of the singing group The Pied Pipers. Tommy soon began featuring her as a soloist largely because she used her voice as a musician would play an instrument. She was one of the most in-tune, on-pitch singers to emerge from the swing era, and she also had excellent voice quality and range. And she swung. Gradually, she became a great favorite with TD audiences, and then went on to a major career as a solo singing artist. (Above left – Jo Stafford pictured in front of a window on an upper floor at the Essex House in NYC – 1940s.)

The final half chorus has the band blasting away atop Rich’s rocking drums. The massed trumpet high notes in this passage provide a thrilling climax to this performance.

The recording presented in this post was digitally remastered by Mike Zirpolo.

Notes:

(1) This refers to the original Squibb Building, 745 Fifth Avenue at 58th Street, which was built in 1930.

(2) Dave Tough, Tommy’s regular drummer through 1937, was beset by various health problems during that year, and was away from the band periodically, usually for short periods of time. At some point, Tommy hired Moe Purtill to stand by for those times when Tough was unable to perform. Eventually, Tough left the Dorsey band, and joined Bunny Berigan in mid-January 1938. By then, Purtill was TD’s full-time drummer.

(3) Decades after the 1930s, Herb Sanford wrote a book of reminiscences about Tommy Dorsey’s Raleigh-Kool radio show, and more generally about Tommy and his brother Jimmy, called: Tommy and Jimmy – The Dorsey Years, (1972), referred to hereafter as Sanford.

(4) Sanford, 107-108.

(5) Sanford, 111-112.

(6) In addition to working at Paramount all day to make Las Vegas Nights, Tommy and his band were working at night at the new Palladium Ballroom, and were also broadcasting another sponsored network radio show on NBC. Somehow, they also found time to make two recording sessions for Victor during the time they were in Hollywood in the fall of 1940. The work load of a top band during the swing era was crushing.

(7) Bing Crosby – Swinging on a Star …The War Years – 1940-1946, (2018), by Gary Giddins, 100-101.

Links:

For more about Tommy Dorsey and Sy Oliver, check out these links:

https://swingandbeyond.com/2016/12/01/on-the-air-with-the-great-bands-1940-tommy-dorsey-hallelujah/

https://swingandbeyond.com/2016/03/25/76/

https://bunnyberiganmrtrumpet.com/2018/01/16/berigan-with-tommy-dorsey-1940-episode-two/

Glad to find you shining the spotlight on TD, Sy, and Jo, my favorites in their respective roles of trombonist, arranger and vocalist, as well as this jubilant side, “Yes Indeed!” I’m sure you’ve come across Sy’s comments, here and there, on how the Oliver-Stafford duet came about: He had originally intended the vocal to be done by the band, but the musicians proved incapable of achieving the effect he wanted, so Tommy suggested that Sy just sing it himself. With little session time remaining, Sy reworked the arrangement for him and Jo, and she got what he was after right away. I believe he said, too, that they pulled it off in one take. Ziggy’s unmistakable lead and Buddy’s impeccable support make a great contribution to the exultant mood of Sy’s majestic arrangement. I’m not aware of any interracial pop duets that preceded this one; the O’Day-Eldridge “Let Me Off Uptown” with Krupa was cut a few months after “Yes Indeed!”

Another great post, Michael.

BBD&O was the epitome of advertising when I worked at WHBC from1978-2010. Probably still is. TDorsey must have been one heck of a self marketer. One needed to be when competing for radio exposure in the 30’s and 40’s. Or any other era.

“Yes Indeed!” was one of many excursions into the “gospel/spiritual” genre made by Dorsey, the most successful (in my opinion) being “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” In the ’50s, Dorsey revisited the genre with such recordings as “Judgment is Coming,” “Where is that Rock,” “This is What Gabriel Said,” and “How Far is it to Jordan.” It seems to me that at least part of the inspiration for all of these arrangements was Bob Haggart’s “I’m Praying Humble.”

Deane Kincaide, who arranged the great “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” worked alongside Bob Haggart in the Bob Crosby orch., so it’s probable that there was some cross-pollination. The harmonizations are similar in the two pieces.

Jo Stafford re-recorded this tune in 1963 on a Tommy Dorsey tribute album. Sammy Davis performed the Sy Oliver vocal. IMHO he overdid some of it. The arrangers for the album are listed as Nelson Riddle, Billy May and Benny Carter. To my ears it doesn;t sound like Riddle or May. so I’ll make a guess that Benny Carter did the arrangement. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IsdXgHUAFM8

I’m sure that it was Carter who arranged “Yes Indeed!” for Jo’s Getting Sentimental Over Tommy Dorsey album. And, yes indeed, Sammy does go overboard in getting religion. Jo, however, is marvelous, as always.