If rock and roll is a religion, then Sun Studio is one of its holiest temples. The walls of this garage-turned-recording-studio in Memphis reverberate with the echoes of the past. This is where Elvis became king, Cash walked the line, and Perkins put on his blue suede shoes. This is where Roy Orbison, B.B. King, Ike Turner, and Jerry Lee Lewis all got their start. This is where rock and roll was born.

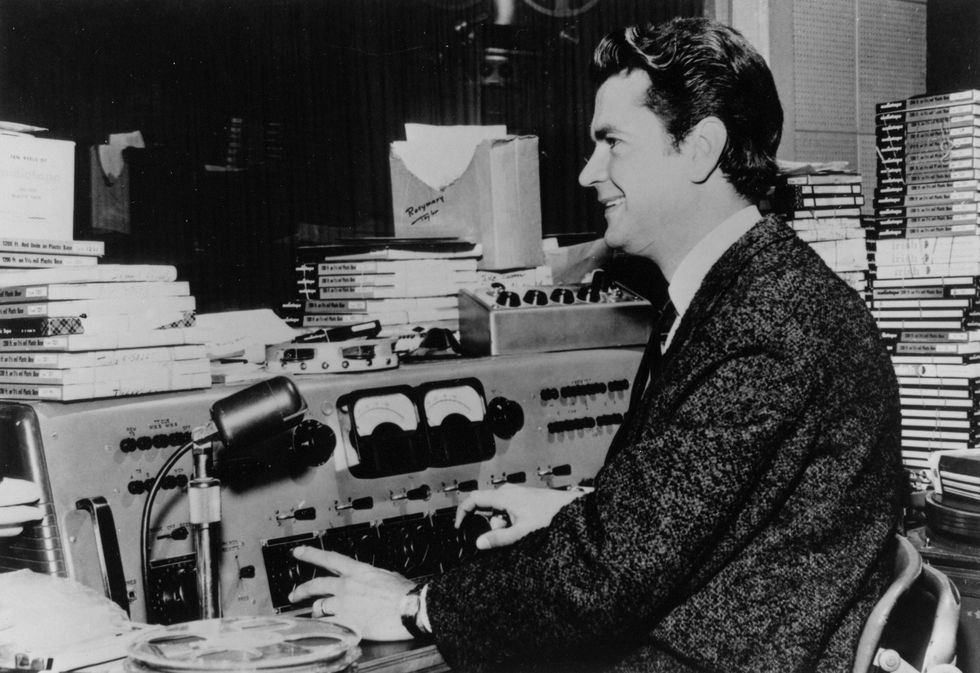

Behind every guitar riff, drum beat, and lyrical innuendo, there was the man in the control room who engineered it all. Sam Phillips helped turn poor boys, sharecroppers' sons, and ex-servicemen into legends, icons, and superstars. "He was always trying to invent sound," says Sam's son, Jerry Phillips, "He felt the studio was his laboratory."

Doing Something Different

Sam Phillips' beginnings were about as unglamorous as those of the many artists he worked with. Born in a small Florence, Alabama farm house in 1923, Phillips was a son of a tenant farmer. Music was part of Sam's life at an early age, from the town's square dances to the summer's eve banjo to the spiritual hymns that rose from the sharecropping fields. He played the sousaphone, trombone, and drums in high school and led his school's 72-piece marching band. Despite this love for music, Sam thought he was destined for something else. Phillips explained in a 2001 Salon interview, "When I was growing up, I wanted to be a criminal defense lawyer, because I saw so many people, especially black people, railroaded."

Then, in 1939, the Phillips family took a trip to see the Baptist pastor George W. Truett in Dallas. Along the way they stopped in Memphis. According to Peter Guralnick's 2015 book Sam Phillips: The Man who Invented Rock'n'Roll, this pit stop was the most influential event in the boy's life. When he arrived in the middle of the night in the pouring rain, Phillips found the streets were alive with people, excitement, and music. Six years later, still drawn to the city, Phillips moved to Memphis to become a disc jockey and engineer at the radio station WREC, broadcasting from the famed Peabody Hotel.

Part of Phillips' job at WREC was to record live performances for later broadcast, but rather than focusing his energies on how the music sounded live, he was most passionate about making sure the recorded product was sublime. "He felt that the rhythm section (the bass and drums) needed to be enhanced... so he would push the microphones closer in (onto the instruments)," says Sun Studio's current engineer Curry Weber, "That was so unorthodox at the time, but the station's owner really loved the way the broadcast sounded on the radio."

"He always said that if you are not doing something different," explains former Sun Studio engineer Matt Ross-Spang, recalling Phillips' personal motto, "you are not doing anything at all."

The Old Repair Shop

From his early childhood, Phillips believed there was a vital kind of music that just wasn't being heard by the average American ear. In 1948, WDIA—WREC's competitor—became the first radio station in the country programmed entirely by African-Americans for African-Americans. Still, a lack of recording studios open to Memphis' African-American musicians limited their opportunity to make money and kept predominant African-American genres of music like blues and jazz isolated. As Guralnick's book puts it, Phillips knew "there was great art to be discovered in the experiences of those who had been marginalized and written off because of their race, their class, or their lack of formal education."

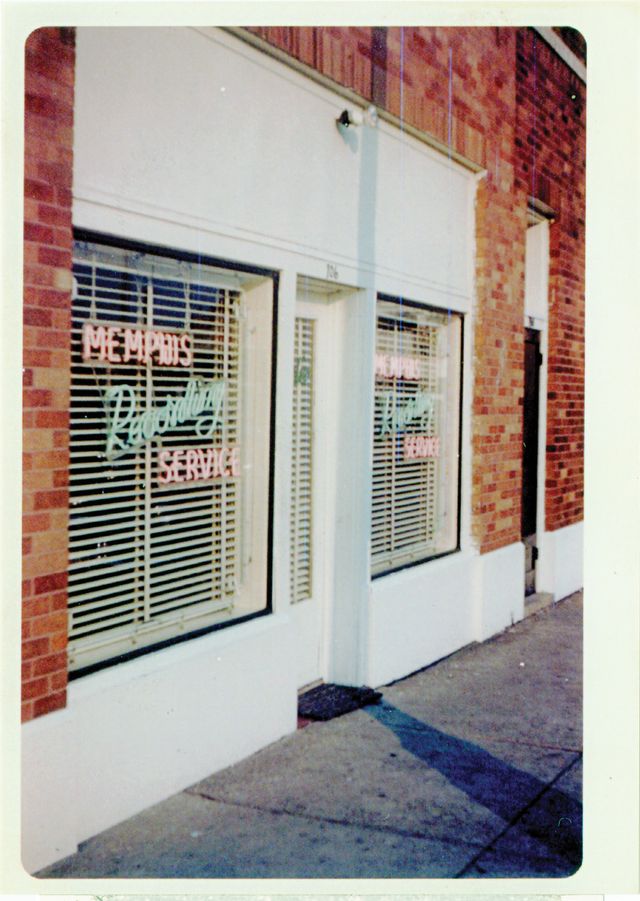

In 1949, while still working at the radio station, Phillips signed a lease for an old automobile glass repair shop next to a diner with odd dimensions and a tin ceiling. Several months later, on January 3rd, 1950, the doors were open to Memphis Recording Service.

This converted car garage was not, at least initially, an ideal setting for a recording studio. Phillips tore out the tin roof and put up acoustic tiles, but still had trouble making the sound consistent. According to Guralnick, Phillips would pace the room one inch at a time, clapping to try to figure out the exact reverb and echo of every single spot in his studio. To this day, Weber says the room remains a mystery, "The sound changes depending where you place instruments… even if you are moving them just a few feet."

In addition, most of the technology available at the time was designed for recording raucous live performances, not the subtle art of capturing studio sessions. As a former radio engineer, Phillips was familiar with it all, but wasn't planning to use the equipment for its initial intention. He assembled a collection of tech that included a Presto lathe recorder, a number of "coke-bottle" Altecs, several RCA-77 D broadcast mics, a few Shure 55s and a late 1930s converted RCA radio console. Then he was finally able to get to work.

Things were slow that first year at Memphis Recording Service. Phillips welcomed all genres—from bluegrass, to western, to his personal love, the blues—but it was hard to maintain a steady stream of clients. Nonetheless, Phillips was most happy when artists came straight off Beale Street to record. "His whole motivation was to capture music before it got away," Sam's son Jerry recalls. "He wanted (the sound) in its environment, like they would play it at home or on Beale Street." When you listen with that in mind, you'll hear a raw, natural quality to these recordings. In Jimmy DeBerry's "Time Made a Change," for example, you can hear a phone ring in the background. Despite the artist's insistence to take it out from the master, Phillips left it in.

The Glory Years

It was around this time that a baby-faced Beale Street regular came into the studio. His name was Riley King, but everyone called him the "Beale Street Blues Boy," a name that later boiled down to simply "B.B. King." With singles like "Mistreated Woman" and "She's Dynamite," King became one of Phillips' first successful artists, and far from the last.

In early 1951, King recommended Phillips' services to the Mississippi-based band "Kings of Rhythm," led by teenager Ike Turner. In their haste to fix an unlucky flat tire on a road trip to Memphis, one of their amps fell out of the trunk and onto the pavement. Upon arriving at Phillips' studio, guitarist Willie Kizart plugged in the amp and got a horrible, fuzzy, distorted noise. The speaker cone of the vacuum tube amp seemed to have broken in the fall, or maybe was damaged during a rainstorm that befell the band on their way to the studio. Whatever the case, the amp was shot and the group, crestfallen, feared their shot at recording a song was over before it had even started.

Phillips, however, had a different idea. Running to the diner next door, he grabbed some paper—the legend differs on whether it was brown paper or day-old newspaper—and stuffed it into the amp, giving it a new, unique sound, a muffled saxophone-like bass. For Phillips, this wasn't just a quick fix, but in fact something better: something different. When you listen to the the song widely hailed as rock and roll's first, "Rocket 88," you'll hear exactly what he created. A sound that helped launch a genre.

"Instead of trying to hide that sound," says Jerry Phillips, "he brought it to the forefront." While this may not have been the first instance of fuzz tone or distortion in a song, it was the first commercially successful song with this soon-to-be-iconic manipulation of sound that would go on to define songs from The Kinks' "You Really Got Me Going" to The Rolling Stones' "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" to The Beastie Boys' "Sabotage."

In February 1952, Phillips founded his own record label, Sun Records, and changed his studio name to match. It was only a year later that an then-unknown Mississippi teen walked through Sun Studio's doors. Elvis Presley, barely eighteen years old, wanted to pay four dollars to a record a song or two for his mother. Sam Phillips put him on a record. "Sam and Elvis were kindred spirits because Elvis was into all the records my dad was recording," Jerry Phillips recalls,"B.B. King, Howlin' Wolf, Roscoe Gordon, Ike Turner... Elvis was listening to all that stuff."

The tracks that Elvis recorded at Sun Studio in 1954 and 1955 have taken on a mythical quality, in part because of the historical significance, in part because you can hear the greatness emerging if you listen closely. Phillips understood that to bring out the budding superstar's talent, he had to surround him with great musicians, like Bill Black on bass and Scotty Moore on guitar, but also allow the recording to be raw to showcase the singer's stunning gift. During most of these recordings, Phillips merely moved the mics and pressed record. By 1955, Elvis was off to RCA and wanted to Phillips to come along, but Phillips stayed at his own label, unwilling to let a corporation meddle in the process he was perfecting.

For the next two years, Sun Studio continued to be Sam Phillips' laboratory. While helping to launch the careers of Jerry Lee Lewis, Howlin' Wolf, Carl Perkins, Roy Orbison and Johnny Cash, he remained the mad genius of sound. In 1954, Phillips acquired two state-of-the-art Ampex 350 tape recorders and started playing around with what we now call "slapback echo delay"—the echo that results when you record to one tape machine's record head while also recording the playback (usually the vocals) being played on another machine. The actual physical space between the heads of the machines makes for an audible delay and echo, a unique and iconic sound best heard on tracks like Elvis' "Blue Moon of Kentucky." It soon became one of Phillips' main tricks, and one that few others knew how to do correctly.

In 1956, Elvis wanted wanted to use the slapback echo on his first RCA single, "Heartbreak Hotel." So RCA called Phillips, but he stubbornly refused to explain the technique. Trying desperately to mimic the sound, RCA instead recorded Elvis in a hallway. There's certainly an echo on the recording, but doesn't come close to what Phillips had done. It was a gaffe that cemented Phillips' style not only as unique and vital, but also impossible to copy.

The Legacy

Phillips' sound hacks can be heard on on countless songs from the last half century of popular music. He used his secretary's office as an echo chamber, creating a makeshift sound that the Doors mimicked in "LA Woman." During the recording of "Blue Suede Shoes" with Carl Perkins, Phillips put cardboard boxes over the amplifiers, turned them around to face a wall and mic'd the amplifiers from behind, resulting in a wonderful, rattling, muffled sound. He often did one take of a song, mixing it live with the rock-solid belief that energy and excitement was more important than perfection. And his intuition was right. Despite pushback from the artists, the famed mastered releases of Elvis' "That's All Right" and "Midnight Train" as well as Perkins' "Blue Suede Shoes" were all from the first take. "He was just a part of the band as the band was," Jerry Phillips says, "The things he was doing behind the board, the moves he was making with the sliders...he was actually playing the board as an instrument."

Today, Jerry Phillips, his brother Knox, his daughter Halley, and his cousin Judd still run the family-owned Sam Phillips Recording Services. Even 60 years later, both studios are still embracing Phillips' innovations which will have already lived on long past his death in July 2003. Jerry Phillips thinks that if his father was alive today, he would have loved modern technologies like Pro Tools, but as means to enhance music, never to create. To make each song sound the most like itself, rather than to make every song sound perfectly the same.

After all, if you are not doing something different, you are not doing anything at all.

Matt is a history, science, and travel writer who is always searching for the mysterious and hidden. He's written for Smithsonian Magazine, Washingtonian, Atlas Obscura, and Arlington Magazine. He calls Washington D.C. home and probably tells way too many cat jokes.