“We All Grow Together”: A Conversation With Stone Gossard

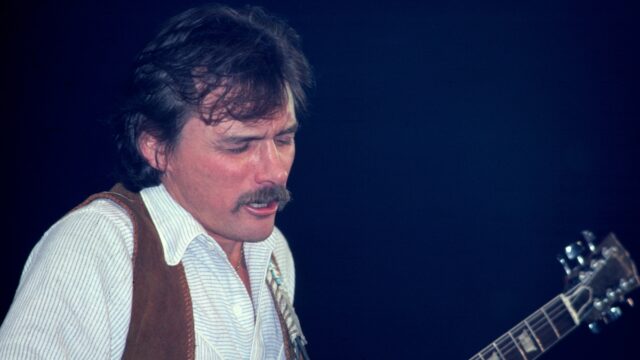

The Pearl Jam guitarist on Painted Shield, his project with Mason Jennings, and what the future of touring holds for rock’s most revelatory live band.

by David Fricke

“We rehearsed right up until we were ready to go,” says guitarist Stone Gossard of Pearl Jam, recalling the energy and anticipation at the start of this year, as that band was about to hit the road in support of its 11th studio album, Gigaton. “We had done 10 days, as much as we ever rehearse, and it was poppin’.”

Then, on March 9, as the coronavirus raged across Europe and began its assault on America, Gossard, guitarist Mike McCready, bassist Jeff Ament, drummer Matt Cameron and singer Eddie Vedder announced the postponement of the first U.S. leg of their tour; a month later, they rescheduled the European dates for 2021. “The gear was on the East Coast, ready for us to go out,” Gossard continues, “when it became evident that this was going to get more serious.”

Instead, Gossard spent his 2020 at home in Seattle — “Doing a lot of virtual school and cleaning up after the kids,” he says — and working at Studio Litho, his recording facility in the city. The guitarist, 54, also completed Painted Shield, his first album with a band of the same name that began in 2014 as a collaboration with Minneapolis-based singer-songwriter Mason Jennings. The project was fleshed out with veteran session drummer Matt Chamberlain and Brittany Davis, a keyboard player and vocalist from Seattle. Their nine-track debut, largely recorded in a long-distance exchange of ideas and sound files, was “about 70 to 80 percent done when the pandemic hit,” Gossard says. “Then we got it over the finish line,” and it became the first release in two decades on his revitalized Loosegroove Records label, founded in 1994 with Regan Hagar, the drummer in Gossard’s long-running side combo Brad.

Opening with the chiming guitar and haunted-keyboard spell of “Orphan Ghost,” Painted Shield is a constantly shifting experience: the thick, grunting guitars and gospel-chorale icing of “Time Machine”; the dense glam tensions coursing through “Knife Fight”; the title song’s hallucinatory layers of psychedelic guitars and singing — all bound by a “rough-hewn aesthetic,” as Gossard puts it, remarkable for a band that hasn’t yet played together in the same room. “People talk about making live records where you hope for the best take,” the guitarist notes. “But they still go back and tinker — add things, replace the bass.” Making Painted Shield, he says, was “a conscious act of sharing, incorporating a multitude of perspectives,” including contributions from Ament and McCready, A-list rock drummer Josh Freese and Seattle artists Jeff Fielder and Om Johari.

“It’s been a fun experiment, and it’s continuing,” Gossard adds. “We’ve recorded another half-a-record already. But something different is going to happen when we do play live. The opportunities and elements will open up in another way.”

Pearl Jam were one of the first big acts to postpone a major tour because of the pandemic — a striking sign of what was ahead.

We wanted to be responsible. You live and fight another day. Trying to get in 10 shows before a tour was cancelled didn’t make sense to us. We were able to see that clearly, rather than pushing it. When you book a tour and there’s a new record, you have a lot of money on the table. You’ve got fans and a crew to take care of. There’s nothing that says, “Don’t go” — unless the band actually says, “We’re not going.” I was proud that we were able to do that.

Was it frustrating to have a new album and nowhere to play the songs live?

We got the new songs up and running in rehearsal. We’ve had lots of records that fizzled a bit in the beginning, but later you find some of your favorite songs are there. We know it’s the long game, and these songs will get a chance. There will be plenty of opportunities to celebrate them. When we get the chance, we’ll be ready to get out there and dance around.

You were working on Painted Shield during the same period that Pearl Jam recorded Gigaton. How did you divide your time and songwriting ideas?

I write a lot, so I have literally hundreds of demos. Ed is who I write for, first and foremost. But I don’t send him big piles of demos. I select a few that make sense. It’s better for him and for the band to bring what’s important, so he’ll do his best to make something happen. When you listen to Gigaton, you hear his ability to manage four other songwriters and bring them into a place that is in tune with his aesthetic, which is very stripped-down and direct.

The writing in Painted Shield is changing dramatically. There is much more material from Matt and Mason directly; they are starting songs, with me playing more of a coloring role. But on this record, 80 percent of it began with a guitar arrangement — a couple of parts, maybe a bridge — and a click track. The song “Painted Shield” began as a demo that I recorded with Matt eight years ago, just messing around at Studio Litho. The drums on “Evil Winds” were played by Josh Freese at least 10 years ago. This came together over long stretches of time.

The album has the driving edge of Pearl Jam but also textures and dynamics that I don’t usually associate with your day job: psychedelia, ’70s funk, Queen-like sheets of harmonies.

It began with Mason and I figuring out how to write a song together. We were sending stuff back and forth, not rushing at all. But at every stage, Mason and I thought, “What makes a great group? What makes a great record?” You have the right blend of perspectives and you make them count. The big elements that made this record stand on its own were Matt Chamberlain’s role — including the songs he brought in at the end [“Orphan Ghost,” “I Am Your Country”] — and Brittany Davis, whose voice blends so well with Mason’s. We want to get into more of that, almost like the singing in X — that neat harmonic interval where the voices become one thing.

How did you connect with Jennings?

Mason’s manager at the time, Dan Fields, is a dear friend of mine. Dan was the tour manager for Ministry on Lollapalooza in 1992 [Pearl Jam were also on the bill]. Mason talked about wanting to collaborate; Dan said, “Maybe Stone will write with you.” That was six years ago. We started with “Knife Fight.” We put that out as a vinyl single, 500 copies. We thought, “If we can do that, we can do anything.”

Was there a point, as the album took shape, where you could hear a band — that kind of unified personality — coming through?

I heard the elements coming together in a way that excited me. I’ve always been a band person. I can’t go out into a room and entertain by myself. My skill set is as a rhythmic pulse, a cheerleader and an arranger. And when you’re lucky to establish a collaborative relationship, you can add to that. Instead of calling this thing Stone Mason and hiring a band, we thought the upside of sharing this was huge. Everybody can participate, and we all grow together. I know that when we get a chance to play together, it’s gonna be a freakout. Brittany and Matt are ridiculously great players. I’ll just be trying to stay out of their way.

What was the impetus for restarting Loosegroove? You had an intense level of activity in the ’90s — including the first album by Queens of the Stone Age and a compilation of Seattle hip-hop — then went quiet in 2000.

It was a big part of my life, but I was overwhelmed by it. I was ready to not have that responsibility anymore. It took Painted Shield and having some Brad music that we want to finish and release to get it started again. Brittany Davis is making a record that I think is amazing. But the one I’m most excited about is the Living — their unreleased album from 1982.

That band is truly a missing link in the Seattle story.

In 1982, the Living were Duff McKagan on guitar and Greg Gilmore, who was later the drummer in Mother Love Bone [with Ament and Gossard]. Todd Fleischman was on bass and the singer was John Conte. I arrived on the scene, going to clubs, two years after they had broken up. But I got to see the bands that Greg and Duff were in after that, the Fartz and 10 Minute Warning, before Duff went to L.A. and started Guns N’ Roses. But the Living made this record, and it’s incredible to hear how influential Duff and Greg were in Seattle music back in ’82. You hear the riffs on this record, and you go, “My God, that’s where Green River [Ament and Gossard’s mid-to-late-’80s band] come from. And that’s like Guns N’ Roses.” We’re going to have so much fun getting this record out. It’s truly great songs and well recorded. It’s a shock that it hasn’t come out yet.

This has been a challenging year for the music business, especially the touring side. What are your expectations for Painted Shield in 2021?

Lucky for us, Painted Shield doesn’t have any experience with touring or even really being together. Our experience so far is recording songs and having people stream them. That’s going well, and I’m optimistic we’ll have another record to solidify our universe next year. That will allow us to do some live shows, figure out where to make an impact. I’m certainly thinking about filming our first rehearsals, to make a live record out of that. It will be a moment of discovery and exploration, and it will be fun to have that on film.

Pearl Jam are set to tour Europe next summer, including two big concerts in London’s Hyde Park. How confident are you that those gigs will happen?

We’re not being unduly optimistic. We’re looking at dates and, as we get closer, we’ll make decisions based on the best information we have at the time. We’re in the worst part of the pandemic now, but we’ve seen the numbers go up and down before. We know there’s a vaccine; there’s a light at the end of the tunnel. But what does that mean to shows for 40,000-plus people?

We’re definitely itching, ready to go, and the gratitude and joy that will come off the stage will be for real. Having not been able to play for so long, we’re never going to look at a live show the same way again.