History of Springfield, Massachusetts

The history of Springfield, Massachusetts dates back to the colonial period, when it was founded in 1636 as Agawam Plantation, named after a nearby village of Algonkian-speaking Native Americans. It was the northernmost settlement of the Connecticut Colony. The settlement defected from Connecticut after four years, however, later joining forces with the coastal Massachusetts Bay Colony. The town changed its name to Springfield, and changed the political boundaries among what later became the states of New England. The decision to establish a settlement sprang in large part from its favorable geography, situated on a steep bluff overlooking the Connecticut River's confluence with three tributaries. It was a Native American crossroad for two major trade routes: Boston-to-Albany and New York City-to-Montreal. Springfield also sits on some of the northeastern United States' most fertile soil.[1]

Springfield flourished for the decades after its founding, operating as a trading post surrounding by numerous colonial farmsteads. The nearby Indian tribes were gradually displaced by colonial settlement and by the late 17th century became gradually confined to a palisaded fort on Long Hill. During King Philip's War, a pan-tribal effort to expel the colonists from their settlements in New England, a successful Indian attack on Springfield destroyed the settlement. After being rebuilt, Springfield's prosperity waned for the next hundred years but, in 1777, Revolutionary War leaders made it a National Armory to store weapons, and in 1795 it began manufacturing muskets. Until 1968, the Armory made small arms.[2] Its first American muskets (1794) were followed by the famous Springfield rifle[3] and the revolutionary M1 Garand and M14s.[4] The Springfield Armory attracted generations of skilled laborers to the city, making it the United States' longtime center for precision manufacturing (comparable to a Silicon Valley of the Industrial Revolution).[2][5] The Armory's near-capture during Shays Rebellion of 1787 was among the troubles that prompted the U.S. Constitutional Convention later that year.[6]

Innovations in the 19th and 20th centuries include the first American English dictionary (1805, Noah Webster), the first use of interchangeable parts and the assembly line in manufacturing (1819, Thomas Blanchard), the first American horseless car (1825, again Thomas Blanchard), vulcanized rubber (1844, Charles Goodyear), the first American gasoline-powered car (1893, Duryea Brothers), the first American motorcycle company (1901, "Indian"), an early commercial radio station (1921, WBZ), and most famously, the world's third-most-popular sport of basketball (1891, Dr. James Naismith).[4][7]

17th century[edit]

Native inhabitants[edit]

It is difficult to estimate the origins of human habitation in the Connecticut River Valley, but there are physical signs dating back at least 9,000 years. Pocumtuck tradition describes the creation of Lake Hitchcock in Deerfield by a giant beaver, which perhaps represents the action of a glacier that retracted at least 12,000 years ago. Various sites indicate millennia of fishing, horticulture, beaver-hunting, and burials. Excavations over the last 150 years have taken many human remains from old burial places, sending them to the collections of institutions such as UMASS Amherst. The passage of the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act in 1990 ordered museums across Western Mass and the country to repatriate these remains to Native peoples, an ongoing process.

The region was inhabited by several Algonkian-speaking Native American communities, culturally connected but distinguished by the place names they assigned to their respective communities: Agawam (low land), Woronco (in a circular way), Nonotuck (in the midst of the river), Pocumtuck (narrow, swift river), and Sokoki (separated from their neighbors). The modern-day Springfield metropolitan area was inhabited by the Agawam Indians.[8] The Agawam, as well as other groups, belong the larger cultural category of Alongkian Indians.

In 1634, Dutch traders triggered a devastating smallpox epidemic in among the region's Native people.[8] Governor Bradford of Massachusetts writes that in Windsor (the site of the Dutch trading post), "of 1,000 of [the Indians] 150 of them died." With so many dead, "rot[ting] above ground for want of burial," English colonists were emboldened to attempt significant settlement of the region.[9]

Colonial settlement[edit]

Puritan fur trader William Pynchon was an original settler of Roxbury, Massachusetts, a magistrate, and then assistant treasurer of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In 1635, he commissioned a scouting expedition led by John Cable and John Woodcock to find the Connecticut River Valley's most suitable site for the dual purposes of agriculture and trading. The expedition traveled either across the inland Bay Path from Boston to Albany via Springfield or, equally likely, along the coast and northward from the mouth of the Connecticut River. It concluded at Agawam where the Westfield River meets the Connecticut River, across the Connecticut River from modern-day Springfield, the northernmost settlement on "The Great River" at that time. The region's numerous rivers and geological history have dictated that its soil is among the finest for farming in the Northeast.[10]

Cable and Woodcock found the Pocomtuc (or perhaps Nipmuck) village of Agawam on the western bank of the Connecticut River. The land near the river was clear of trees due to burns by the Indians, and covered in nutrient-rich river silt from both floods and glacial Lake Hitchcock.[11] Just south of the Westfield River, Cable and Woodcock constructed a pre-fabricated house in present-day Agawam, Massachusetts (at modern-day Pynchon Point.)

On May 15, 1636, Pynchon led a settlement expedition to be administered by the Connecticut Colony, which included Henry Smith (Pynchon's son-in-law), Jehu Burr, William Blake, Matthew Mitchell, Edmund Wood, Thomas Ufford, John Cable,[12] and a Massachusett Indian translator named Ahaughton. Pynchon likely never learned the Algonkian language, making the help of Native interpreters crucial in learning about the land and dealing with its Native inhabitants. Dutch and Plymouth Colonists had been leapfrogging their way up "the Great River," as far north as Windsor, Connecticut, attempting to establish its northernmost village to gain the greatest access to the region's raw materials. Pynchon selected a spot just north of Enfield Falls, the first spot on the Connecticut River where all travelers have to stop to negotiate a waterfall 32 feet (9.8 m) in height, and then transship their cargoes from ocean-going vessels to smaller shallops. By founding Springfield, Pynchon positioned himself as the northernmost trader on the Connecticut River. Near Enfield Falls, he erected a warehouse to store goods awaiting shipment, which is still called "Warehouse Point" to this day, located in East Windsor, Connecticut.[13]

In 1636, Pynchon's party purchased land on both sides of Connecticut River from 18 tribesmen who lived at a palisade fort at the current site of Springfield's Longhill Street. The price paid was 18 hoes, 18 fathoms of wampum, 18 coats, 18 hatchets, and 18 knives.[14][15] Ahaughton was a signatory, witness, and likely negotiator for the deed. The Indians retained foraging and hunting rights and the rights to their existing farmlands, and were granted the right to compensation if livestock owned by colonists ruined their corn crops.[16] As is the case for many Indian deeds, it is dubious whether or not the Native signatories of the document possessed the political authority to sign on behalf of their tribes.[8]

In 1636, the fledgling colonial settlement was named Agawam Plantation and administered by the Connecticut Colony, as opposed to the Massachusetts Bay Colony.[17]

Leaving Connecticut for Massachusetts[edit]

| Town | Date of separation[18] |

|---|---|

| Westfield | 1669 |

| Suffield (CT) (as Southfield) | 1682 |

| Enfield (CT) (as Freshwater) | 1683 |

| Stafford (CT) | 1719 |

| Somers (CT) (from Enfield) | 1734 |

| Wilbraham | 1763 |

| East Windsor (CT) (northern part) | 1768 |

| West Springfield | 1774 |

| Ludlow | 1774 |

| Southwick | 1775 (from Westfield) |

| Montgomery | 1780 (from Westfield) |

| Longmeadow | 1783 |

| Russell | 1792 (from Westfield) |

| Chicopee | 1848 |

| Holyoke (except Smith's Ferry) | 1850 (from W. Springfield) |

| Agawam | 1855 (from W. Springfield) |

| Hampden | 1878 (from Wilbraham) |

| East Longmeadow | 1894 (from Longmeadow) |

In 1640 and 1641, two events took place that forever changed the political boundaries of the Connecticut River Valley. From its founding until that time, Springfield had been administered by Connecticut along with Connecticut's three other settlements: Wethersfield, Hartford, and Windsor. In the spring of 1640, grain became scarce and the Connecticut Colony's cattle were dying of starvation. The nearby Connecticut River Valley settlements of Windsor and Hartford (then called "Newtown") gave power to William Pynchon to buy corn for all three English settlements. If the natives would not sell their corn at market prices, then Pynchon was authorized to offer more money. The natives refused to sell their corn at market prices, and then later refused to sell it at what Pynchon deemed "reasonable" prices. Pynchon refused to buy it, believing it best not to broadcast the English colonists' weaknesses, and also wanting to keep market values steady.[19]

Leading citizens of what would become Hartford were furious with Pynchon for not purchasing the grain. With Windsor's and Wethersfield's consent, the Connecticut Colony's three southern settlements commissioned Captain John Mason, notable for his leadership in the Pequot War (including the Mystic Massacre), to travel to Springfield with "money in one hand and a sword in the other" to acquire grain for their settlements.[20] On reaching what would become Springfield, Mason threatened the Pocumtucs with war if they did not sell their corn at "reasonable prices." The Pocumtucs capitulated and ultimately sold the colonists corn; however, Mason's violent approach deepened Native distrust towards the colonists. Before leaving, Mason also upbraided Pynchon publicly, accusing Pynchon of sharp trading practices and of forcing the Pocumtucs to trade only with him because they feared him. (The three southern Connecticut Colony settlements were surrounded by different tribes than Springfield, i.e. the more warlike Pequots and Mohegans.)

Ultimately, in 1640, Pynchon and the planters of Agawam voted to separate themselves from the other river towns, removing themselves from the jurisdiction of Connecticut Colony. Looking to capitalize on Springfield's defection, the Massachusetts Bay Colony decided to reassert its jurisdiction over land bordering the Connecticut River, including Agawam.

Tensions between Springfield and Connecticut were exacerbated by one final confrontation in 1640. Hartford had been keeping a fort at the mouth of the Connecticut River at Old Saybrook, for protection against various tribes and the New Netherland Colony. After Springfield sided with the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Connecticut, demanded that Springfield's boats pay a toll when passing the Fort at Old Saybrook, (which, at the time, was not administered by the Connecticut Colony, but the short-lived Saybrook Colony.) Pynchon would have been agreeable to this if Springfield could have had representation at the Fort at Saybrook; however, Connecticut refused to allow Springfield a presence at the fort, and thus Pynchon instructed his boats to refuse to pay Connecticut's toll. When the Massachusetts Bay Colony heard about this controversy, it took Pynchon's side and immediately drafted a resolution that required Connecticut ships to pay a toll when entering Boston Harbor. Connecticut, which was then dependent largely on trade with Boston, immediately dropped its tax on Springfield.[19]

When the dust finally settled, Pynchon was named magistrate of Agawam by the Massachusetts Bay Colony and, in honor of his importance, the settlement was renamed Springfield after his place of birth, in England.[19] For decades, Springfield, which then included modern-day Westfield, was the westernmost settlement in Massachusetts.

In 1642, Massachusetts Bay commissioned a definable border to be drawn up, one of the first in what is now America. Led by Nathaniel Woodward and Solomon Saffery, the group left in a border crossing at the old Bissell's Ferry in Windsor, north of today's downtown Windsor and went into a line near what is currently U.S. Route 44. After the results were published, this line greatly benefited the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The towns of Suffield, Enfield, Somers, Stafford, and Granby were placed in the jurisdiction of Springfield lands. Connecticut protested the result, claiming that they didn't even walk but sailed by boat from the Charles River, around Cape Cod and went up to near Enfield Falls. This resulted in one of the longest running border disputes in American history.

Early "firsts"[edit]

In 1645, 46 years before the Salem witch trials, Springfield experienced America's first accusations of witchcraft when Mary (Bliss) Parsons, wife of Cornet Joseph Parsons, accused a widow named Marshfield, who had moved from Windsor to Springfield, with witchcraft—an offense then punishable by death.[21] For this, Mary Parsons was found guilty of slander.

In 1651, a different Mary Parsons was accused of witchcraft, and also of murdering her own child.[21] In turn, Mary Parsons then accused her own husband, Hugh Parsons, of witchcraft. At America's first witch trial, both Mary and Hugh Parsons were found not guilty of witchcraft for want of satisfactory evidence. However, Mary was found guilty of murdering her own child, but died in prison in 1651, before her death sentence could be carried out.[14]

William Pynchon was the New World's first commercial meat packer. In 1641, he began exporting barrels of salt-pork;[14] however, in 1650 he became famous for writing the New World's first banned book, The Meritous Price of Our Redemption.[21] In 1649, Pynchon found time to write the book which was published in London in 1650. Several copies made it back to the Massachusetts Bay Colony and its capital, Boston, which reacted with rage to Pynchon rather than with support. For his critical attitude toward Massachusetts' Calvinist Puritanism, Pynchon was accused of heresy, and his book was burned on the Boston Common. Only 4 known copies survived.[22] By declaration of the Massachusetts General Court, in 1650, The Meritous Price of Our Redemption became the first-ever banned book in the New World.[23] In 1651, Pynchon was accused of heresy in Boston – at the same meeting of the Massachusetts General Court where Springfielder Mary Parsons was sentenced to death.[22] Standing to lose all of his land-holdings – the largest in the Connecticut River Valley – William Pynchon transferred ownership to his son, John and, in 1652, moved back to England with his friend, the Reverend Moxon.[22][24]

William's son, John Pynchon, and his brother-in-law, Elizur Holyoke, quickly took on the settlement's leadership roles. They began moving Springfield away from the diminishing fur trade into agricultural pursuits. In 1655, John Pynchon launched America's first cattle drive, prodding a herd from Springfield to Boston along the old Bay Path Trail.[14]

Purchases of large swaths of land from the Indians continued throughout the 17th century, enlarging Springfield's territory and forming other colonial towns elsewhere in the Connecticut River Valley. Westfield was the westernmost settlement of Massachusetts Bay Colony until 1725, and Springfield was, as it remains today, the colony's most populous and important western settlement.[15] Over decades and centuries, portions of Springfield were partitioned off to form neighboring towns; however, throughout the centuries, Springfield has remained the region's most populous and most important city.

Due to imprecision in surveying colonial borders, Springfield became embroiled in a boundary dispute between the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Connecticut Colony, which was not resolved until 1803–4. (See the article on the History of Massachusetts-Connecticut Border). As a result, some lands originally administered by Springfield – including the William Pynchon's Warehouse Point – are now administered by Connecticut.[15]

Trade and encroachment[edit]

For the next several decades, Native people experienced a complex relationship with the colonists. The fur trade stood at the heart of their economic interactions, a lucrative business that guided many other policy decisions. White settlers traded wampum, cloth and metal in exchange for furs, as well as horticultural produce. Because of the seasonal nature of goods provided by Native people, compared with the constant availability of colonial goods, a credit system developed. Land, the natural resource whose availability did not fluctuate, served as collateral for mortgages in which Native people bought goods from colonists in exchange for the future promise of beavers. However, trade with the colonists made pelts so lucrative that the beaver was rapidly overhunted. The volume of the trade fell, from a 1654 high of 3,723 pelts to a mere 191 ten years later. With every mortgage, Native people lost more land - even as their population base recovered and expanded from previous epidemics of diseases.[25]

In a process that historian Lisa Brooks calls "the deed game", colonists acquired an increasing amount of land from Indian tribes through debt, fraudulent purchases and a variety of other methods.[26] Springfield settler Samuel Marshfield took so much land from the inhabitants of Agawam that they had “little left to plant on,” to the point that the Massachusetts General Court stepped in and forced Marshfield to allocate them 15 acres. Native people began to construct and gather in palisaded “forts” - structures that were not necessary beforehand. The Agawam fort outside of Springfield was on Long Hill, although it is commonly (incorrectly) believed that it stood in a modern-day park called “King Philip’s Stockade.” These sites were excavated in the 19th and 20th centuries by anthropologists, who, as previously noted, took cultural objects and human remains and displayed them for years in area museums. With the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990, a long process of repatriation began.[citation needed]

Tensions between the colonists (including those living in Sprinfield) and surrounding Indian tribes, which had already been poor for some time, continued to deteriorate in the years preceding the outbreak of King Philip's War. Colonial encroachment on Indian lands, combined with the decimation of the native population from European diseases, led to increasing Native resentment and hostility towards the colonists. Though some Indians became integrated into colonial society, with many being employed in white households, numerous pieces of legislation were passed which prevented Indians from marrying settlers and staying in colonial settlements after dark, while colonists were prevented from living among the Indians.[26]

King Philip's War[edit]

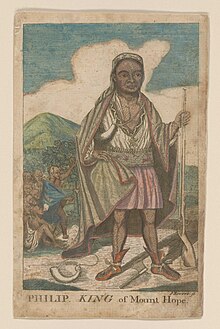

Wamsutta's brother, Chief Metacomet (known to inhabitants of Springfield as "Philip,") began a war against colonial expansion in New England which spread across the region. As the conflict grew in its initial months, colonists throughout Western Massachusetts became deeply concerned with maintaining the loyalty of "their Indians."[27] The Agawams cooperated, even providing valuable intelligence to the colonists.[citation needed]

In August 1675, a group of colonists in Hadley demanded the disarming of a “fort” of Nonotuck Indians. Unwilling to relinquish their weapons, they left on the night of August 25. A hundred colonists pursued them, catching up to them at the foot of Sugarloaf Hill, which was a sacred space for the Nonotucks called the Great Beaver. The colonists attacked, but the Nonotucks forced them to withdraw and were able to keep moving.[28] The shedding of Native blood on sacred land was an attack on their entire kinship network, a reality whose implications were not lost to John Pynchon. He forced the Agawams of Long Hill to send hostages down to Hartford, in a move that he hoped would prevent the Agawam people from fighting alongside their kin. These efforts did not succeed.[citation needed]

In October 1675, warriors from other villages joined the Agawams at their village at Long Hill, preparing for one of the largest battles in King Philip's War. The historian Charles Barrows speculates that prior to carrying out the attack, they sent messengers to Hartford to encourage facilitate the escape of the Agawam hostages being held there. Possibly because these members, a Native man named Toto, who lived between Springfield and Hartford in Windsor and was connected to the Wolcott family, learned of and warned the colonists of Springfield about the impending attack.[29]

On October 5, 1675, despite the advance warning, during the Siege of Springfield, 45 of Springfield's 60 houses were burned to the ground, as were the grist and saw mills belonging to village leader John Pynchon, which became smoldering ruins.[30] Following the Siege of Springfield, serious thought was given to abandoning the village of Springfield and defecting to nearby towns; however, residents of Springfield endured the winter of 1675 under siege conditions. During that winter, Captain Miles Morgan's block-house became Springfield's fortress. It held-out until messengers had been despatched to Hadley, after which thirty-six men (the standing army of the Massachusetts Bay Colony), under command of Captain Samuel Appleton, marched to Springfield and raised the siege. Today, a large bronze statue of Morgan, who lost his son Pelatiah and son-in-law Edmund Prinrideyes in King Philip's War, stands in Springfield's Court Square, showing him in huntsman's dress with a rifle over his shoulder.

During King Philip's War, over 800 settlers were killed and approximately 8,000 Natives were killed, enslaved, or made refugees.[31] Some histories mark the end of the war with the death of Metacom in the summer of 1676, however the conflict extended into present-day Maine, where the Wabanakis succuesfully managed to persuade the colonists to sign a truce after a period of conflict.[26]

Following the war, the greater part of the Native American population left Western Massachusetts behind, although land cessions from Native people to the colonists continued into the 1680's.[32] Many native refugees of the conflict joined the Wabanaki in the north, where their descendants remain today. Native warriors returned to Western Massachusetts alongside the French during the Seven Years' War, and oral histories recall Abenaki visitors to Deerfield as recently as the 1830s.[8]

Today, it is claimed that King Philip incited the Agawam Indians into the attack, on a hilltop now known as King Philip's Stockade. It is a Springfield city park that offers excellent views of the Connecticut River, city skyline, picnic pavilions, and a statue depicting the famous Windsor Indian who tried to warn the residents of Springfield of impending danger. The actual location of the stockaded Indian village is about a mile north, off Longhill Street, on a bluff overlooking the river. In 2005, a group of Native people from the Nipmuc Nation in Worcester performed a rededication ceremony of the "Stockade."[33]

18th century[edit]

The Springfield Armory[edit]

Then as now, a major crossroads, during the 1770s, George Washington selected a high bluff in Springfield as the site of the U.S. National Armory. Washington selected Springfield for its centrality to important American cities and resources, its easy access to the Connecticut River and because, as today, the city served as the nexus for well-traveled roads. Washington's officer Henry Knox noted that Springfield was far enough upstream on the Connecticut River to guard against all but the most aggressive sea attacks. He concluded that “the plain just above Springfield is perhaps one of the most proper spots on every account” for the location of a National Arsenal.[14] During the War of Independence, the arsenal at Springfield provided supplies and equipment for the American forces. At that time, the arsenal stored muskets, cannons, and other weapons; it also produced paper cartridges. Barracks, shops, storehouses, and a magazine were built, but no arms were manufactured. After the war the government retained the facility to store arms for future needs.

By the 1780s, the Arsenal was the United States' largest ammunition and weapons depot, which made it the logical focal point for Shays' Rebellion (see below).[34] On the recommendations of then U.S. President George Washington, Congress formally established the Springfield Armory in 1794. In 1795, the Springfield Armory produced the first American-made musket, and during that year, produced 245 muskets.[4] Until its closing in 1968, the Armory developed and produced a majority of the arms that served American soldiers in the nation's successful wars. Its presence also set Springfield on the path of industrial innovation that would result in the city becoming known as the "City of Progress" [35][36][37] and later as the "City of Firsts."

The term Springfield Rifle may refer to any sort of arms produced by the Springfield Armory for the United States armed forces. Other famous arms invented in Springfield include the Repeating Pistol, and the Semi-automatic M1 Garand.[38]

The 55 acres (220,000 m2) within the Armory's famous ornamental cast-iron fence are now administered by Springfield Technical Community College and the National Park Service. Most of the buildings were erected during the 19th century, with the oldest dating from 1808. The complex reflects the Armory commanders’ goal of creating an institution with dignity and architectural integrity worthy of the increasing strength of the federal government.

Shays' Rebellion[edit]

Shays's Rebellion – the most crucial battle of which was fought at the Springfield Armory in 1787 – was the United States' first populist revolt. It prompted George Washington to come out of retirement, and catalyzed the U.S. Founding Fathers to craft the U.S. Constitution. On May 25, 1787, General Henry Knox, the Secretary of War, addressed the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia: “The commotion of Massachusetts have wrought prodigious changes in the minds of men in the State respecting the Powers of Government... They must be strengthened, there is no security of liberty or property.” [39]

Shays' Rebellion was led, in part, by American Revolutionary War soldier Daniel Shays. In January 1787, Shays and the "Regulators" as they were then called, tried to seize the Arsenal at Springfield. The Arsenal at Springfield was not yet an Armory; however, it contained brass ordnance, howitzers, traveling carriages, muskets, swords, various military stores and implements, and many kinds of ammunition.[40] If the Regulators had captured the Arsenal at Springfield, they would have had far more firepower than their adversaries, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, led by former U.S. General Benjamin Lincoln.

Court at Springfield shut down by angry mob[edit]

In July 1786, a diverse group of Western Massachusetts gentlemen, farmers, and war veterans – often characterized as "yeoman farmers" by the Massachusetts and Federal governments, convened in Southampton, Massachusetts, to write-up a list of grievances with the 1780 Massachusetts State Constitution. Among, the conventioneers was William Pynchon, the voice of Springfield's – and the Connecticut River Valley's – most powerful family. The convention produced twenty-one articles – 17 were grievances, necessitating radical changes to Massachusetts' State Constitution. They included moving the Massachusetts State Legislature out of Boston to a more central location, where Boston's mercantile elite could no longer control the state government for its own financial gain; abolishing the Massachusetts State Senate, which was dominated by Boston's merchants and was in essence a redundant given that Massachusetts already had a State Legislature that dealt with similar issues; and revising election rules so that State Legislators would be held accountable yearly via elections. Grievances were also voiced about Massachusetts' excessively complex, seemingly money-driven court system and the scarcity of paper money to pay state taxes.

Rather than address the Southampton Convention's grievances, both houses of the Massachusetts State Legislature went on vacation. After this, "Regulators" began gathering in mobs of thousands, forcing the closure of Massachusetts' county courts. The Regulators shut down court proceedings in Northampton, Worcester, Concord, Taunton, Great Barrington, and then finally, even the Supreme Judicial Court in Springfield.

Massachusetts' Governor Bowdoin – along with Boston's former patriots, like Samuel Adams, who had, it seemed, lost touch with common people – were zealously unsympathetic to the Regulators' cause. Samuel Adams wanted the Regulators "put to death immediately." In response, Governor Bowdoin dispatched a militia financed by Boston merchants led by former Revolutionary War General Benjamin Lincoln, as well as a militia of 900 men led by General William Shepard to protect Springfield.[41] The militia members, however, generally sympathized with the Regulators and more often than not, defected to the Regulators rather than remain with Massachusetts' militia. News of the Rebellion in Western Massachusetts reached the Continental Congress in late 1786. The Congress authorized troops to put down the rebellion; however, the government insisted that it was for fighting Indians in Ohio. In the Massachusetts State Legislature, Elbridge Gerry noted that the 'fighting Indians in Ohio' excuse was "laughable."[42]

The Battle of the U.S. Arsenal at Springfield[edit]

By January 1787, thousands of men from Western Massachusetts, Eastern New York, Vermont, and Connecticut had joined the Regulators; however, many were scattered across the expanse of Western Massachusetts. On January 25, 1787, three major Regulator armies were coalescing on Springfield in attempt to overtake the U.S. Federal Arsenal at Springfield. The armies were commanded by, respectively, Daniel Shays, whose army was camped in nearby Palmer, Massachusetts; Luke Day, whose army was camped across the Connecticut River in West Springfield, Massachusetts; and Eli Parsons, whose army was camped just north of Springfield in Chicopee, Massachusetts. The plan for commandeering the Arsenal at Springfield was for a three-pronged attack on January 25, 1787; however, the day before the scheduled attack, General Luke Day unilaterally postponed the attack to January 26, 1787. Day sent a note postponing the attack to both Shays and Parsons; however, it never reached them.

On January 25, 1787, Shays's and Parson's armies approached the Arsenal at Springfield expecting Day's army to back them up. General William Shepard's Massachusetts militia – which had been withered by defections to the Regulators – was already inside the Arsenal. General Shepard had requested permission from U.S. Secretary of Defense Henry Knox to use the weaponry in the Arsenal, because technically its firepower belonged to the United States, and not the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Secretary of War Henry Knox denied the request on the grounds that it required Congressional approval and that Congress was out of session; however, Shepard used the Arsenal's weapons anyway.[43]

When Shays, Parsons, and their forces neared the Arsenal, they found Shepard's militia waiting for them – and they were baffled by the location of Luke Day's army. Shepard ordered a warning shot. Two cannons were fired directly into Shays's men. Four of the Shaysites were killed, and thirty were immediately wounded. No musket fire took place. The rear of Shays's army ran, leaving his Captain James White "casting a look of scorn before and behind," and then fled. Without reinforcements from Day, the rebels were unsuccessful in taking the Springfield Arsenal.

The militia captured many of the rebels on February 4 in Petersham, Massachusetts. Over the course of the next several weeks, the rebels were dispersed; however, skirmishes continued for approximately a year thereafter.

Governor Bowdoin declared that Americans would descend into "a state of anarchy, confusion, and slavery" unless the rule of the law was upheld.[44] Shays's Rebellion, however, was – like American Revolution – an armed uprising against a rule of law perceived to be unjust.[45] Ultimately, Shays's Rebellions' legacy is the United States Constitution.

19th century[edit]

The City of Progress[edit]

The City of Springfield, and, in particular, the Springfield Armory played an important role in the early Industrial Revolution. As of 2011, Springfield is nicknamed The City of Firsts; however, throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, its nickname was The City of Progress.[35][36][37] Throughout its history, Springfield has been a center of commercial invention, ideological progress, and technological innovation. For example, in 1819, inventor Thomas Blanchard and his lathe led to the uses of interchangeable parts and assembly line mass production, which went on to influence the entire world – while originally making arms production at The Springfield Armory faster and less expensive.[47] Blanchard – and Springfield – are credited with the discovery of the assembly line manufacturing process.[38] Blanchard also invented the first modern car in Springfield, a "horseless carriage" powered by steam.[48]

The first American-English dictionary was produced in Springfield in 1806 by the company now known as Merriam Webster.[4] Merriam Webster continues to maintain its worldwide headquarters in Springfield, just north of the Springfield Armory.

In Springfield, "The City of Progress," many products were invented that are still popular and necessary today. For example, in 1844, Charles Goodyear perfected and patented vulcanized rubber at his factory in Springfield. (The automobile had not yet been invented, so Goodyear patented his rubber stamp rather than tires, for which he later became known). In 1856, the world's first-ever adjustable monkey wrench was invented in Springfield. In 1873, America's first postcard was invented in Springfield by the Morgan Envelope Factory.[4] Also, America's first horse show and dog show were both produced in Springfield – 1853 and 1875, respectively.[4]

Well known for it “firsts," Springfield also has the distinction of being the last New England city to free another state's slave. In Massachusetts, the cruel institution was outlawed by 1783, in a court decision based on the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution. In 1808, a man from New York – where slavery, at the time, was legal – came to Springfield demanding the return of his escaped slave: a woman named Jenny who had been living in Springfield for several years. In a show of support for abolitionism, the citizens of Springfield, among them Bezaleel Howard, raised enough money to buy Jenny's freedom from the New Yorker. Jenny lived a free woman in Springfield thereafter.[14]

John Brown, the celebrated abolitionist and hero of John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, became a national leader in the abolitionist movement while living in Springfield. Indeed, Springfield's role in the abolitionist movement was far greater than the city's population at the time, (approximately 20,000 before the separation of Chicopee). In 1836, Springfield's American Colonization Society was its first radical abolitionist group. Nearly all Springfielders – from its wealthiest merchants to its influential newspaper publisher – supported abolitionism. In 1846, Brown moved into this progressive climate and set up a wool commission. Brown began attending church services at the traditionally black Sanford Street Church (now St. John's Congregational Church.) In Springfield, Brown spoke with Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth, while learning about the successes of Springfield's Underground Railroad. Also, in Springfield, Brown met many of the contacts he would need in later years to fund his work in Bleeding Kansas.[14] In 1850, in response to the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, John Brown formed his first militant anti-slavery organization in Springfield: The League of Gileadites. Brown founded the group by saying, "Nothing so charms the American people as personal bravery. [Blacks] would have ten times the number [of whites friends than] they now have were they but half as much in earnest to secure their dearest rights as they are to ape the follies and extravagances of their white neighbors..."[49] The League of Gileadites protected slaves who escaped to Springfield from slaver-catchers. After the foundation of Brown's organization in 1850, a slave was never again "captured" in the city. As of 2011, St. John's Congregational Church – one of the Northeast's most prominent black congregations, now celebrating its 167th year in existence – still displays John Brown's Bible.[50]

Even following the Civil War, Springfield remained a locus of early black culture, as the place where Irvine Garland Penn's The Afro-American Press and Its Editors was first published in 1891. Among the notable residents of the city was Primus P. Mason, a real estate investor of the city for whom Mason Square is so named, who donated his estate to found the Mason-Wright Retirement Home. In his book Efforts for Social Betterment Among Negro Americans W.E.B. DuBois described Mason as "one of the chief Negro Philanthropists of our time" for his creation of what Mason himself wrote in his will of "a place where old men that are worthy may feel at home".[51]

In 1852, Springfield was chartered as a city; however, only after decades of debate, which, in 1848, resulted in the partitioning off of the northern part of Springfield into Chicopee, Massachusetts – in order to reduce Springfield's land and population. The partition of Chicopee from Springfield deprived Springfield of approximately half of its territory and approximately two-thirds of its population. To this day, the two cities of Springfield and Chicopee have relatively small land areas and remain separate.[21] Springfield's first mayor was Caleb Rice, who was also the first President of MassMutual Life Insurance Company. As of 2011, the MassMutual Life Insurance Company, headquartered in Springfield, is the second wealthiest company from Massachusetts listed in the Fortune 100.

Wason Manufacturing Company of Springfield – one of the United States' first makers of railway passenger coach equipment – produced America's first sleeping car in 1857, (also known as a Pullman Car).[4] On May 2, 1849, the Springfield Railroad was chartered to build from Springfield to the Connecticut state line. By the 1870s the endeavor had become the Springfield and New London Railroad.

In 1855, the formation of the Republican Party was championed by Samuel Bowles III, publisher of the influential Springfield daily newspaper, The Republican. The Republican Party took its name from Bowles' newspaper.[14] On Friday, September 21, 1855, the headline in The Republican read: “The Child is Born!” This marked the birth of the Republican Party. By 1858, the Republicans had taken control of many Northern States' governments. In 1860, Bowles was on the train to the Republican convention in Chicago where his friend, Springfield lawyer George Ashmun, was elected chairman of the convention that would eventually nominate Abraham Lincoln for president.[14]

In 1856, Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson formed Smith & Wesson to manufacture revolvers. Smith & Wesson has gone on to become the largest and, it can be argued, the most famous gun manufacturer in the world. The company's headquarters remains in Springfield and as of 2011, employs over 1200 workers.

By 1870 the expansion of industry had created the opportunity for the creation of a trolley system; the Springfield Street Railway began horsecar service on March 10, 1870, followed by its first electric line in Forest Park two decades later on June 6, 1890. By 1905 the city had more track than New York City at that time, and the lines drove the success of suburbs like McKnight as workers began commuting further distances.[52]

On September 20, 1893, Springfielders Charles and Frank Duryea built and then road-tested the first-ever American, gasoline-powered car in Springfield.[53] The Duryea Motor Wagon was built on the third floor of the Stacy Building in Springfield, and first publicly road-tested on Howard Bemis's farm.[54][55] In 1895, the Duryea Motor Wagon won America's first-ever road race – a 54-mile (87 km) race from Chicago to Evanston, Illinois. In 1896, the Duryea Motor Wagon Company became the first company to manufacture and sell gasoline-powered automobiles. The company's motto was "there is no better motorcar." Immediately, Duryeas were purchased by luminaries of the times, such as George Vanderbilt.[53] Two months after buying one of the world's first Duryeas, New York City motorist Henry Wells hit a bicyclist – the rider suffered a broken leg, Wells spent a night in jail – and that was Springfield's peripheral role in the first-ever automobile accident.[53]

In 1899, the Springfield Ethnological and Natural History Museum (now the Springfield Science Museum) opened in its new building on October 16, 1899.[56][57] Prior to this, the museum had existed as a curiosities collection established in December 1859 in City Hall, later hosted at the City Library beginning in 1871.[56][58]

The birthplace of basketball[edit]

Today, the city of Springfield is known worldwide as the birthplace of the sport of basketball. In 1891, James Naismith, a theology graduate, invented the sport of basketball at the YMCA International Training School – now known as Springfield College – to fill-in the gap between the football and baseball seasons. The first game of basketball ever played took place in the Mason Square district of Springfield. (The game's score was 1 – 0). As of 2011, the exact spot where the first game took place is memorialized by an illuminated monument. The first building to serve as an indoor basketball court resides at Wilbraham & Monson Academy in suburban Wilbraham, and has since been converted into a dormitory (Smith Hall). In 1912, the first ever specifically crafted basketball was produced in Springfield by the Victor Sporting Goods Company.[4] As of 2011, Springfield-based Spalding is the world's largest producer of basketballs, and produces the official basketball of the National Basketball Association.[59]

Basketball became an Olympic sport in 1936, and since its burst of popularity during the 1980s and 1990s, has gone on to become the world's second most popular sport (after soccer).

On February 17, 1968, The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame was opened on the Springfield College campus. In 1985, it was replaced by a larger facility on the bank of the Connecticut River. In 2002, a new, architecturally significant Hall of Fame was constructed next to the existing site, (which was subsequently converted into restaurants and an LA Fitness club). Shaped like a giant basketball and illuminated at night, the Basketball Hall of Fame is currently one of the most architecturally recognizable buildings recently constructed in Springfield.

Today, both amateur and professional basketball are an integral part of Springfield's culture. Springfield's professional basketball team, the NBA Development League Springfield Armor – the official affiliate of the Brooklyn Nets – play in the MassMutual Center, several blocks from the Basketball Hall of Fame and the site of the first-ever basketball game. Basketball-related events take place in Springfield year-round, including the Basketball Hall of Fame's annual enshrinement ceremony, the NCAA's college basketball Tip-Off Tournament, the NCAA MAAC division tournament, and the high school Hoop Hall Classic, among numerous other basketball-related events. Many non-basketball-related events in Springfield also draw inspiration from the sport; for example, the annual Hoop City Jazz Festival brings jazz greats and tens of thousands of people to the "Hoop City."

"Art & Soles", a 2010 public art installation in Springfield, featured 6-foot (1.8 m) painted basketball shoes commemorating the city's history as birthplace of basketball and home of the Hall of Fame. Each of the nineteen shoes was painted by a local artist and displayed in a prominent location in the downtown area, with the overall goal of providing an artistic answer to the question “What Makes Springfield Great?”[60] The shoes were sold at auction in March 2011 with the proceeds going to support public art in Springfield.[61][62]

20th century[edit]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The Duryeas were joined in Springfield's automobile industry in 1900 by Skene, (which disappeared shortly after), and Knox Automobile, which survived until 1927.[63] In 1905, Knox famously produced America's first motorized fire engines for Springfield's Fire Department – the first modern fire department in the world.[4]

In 1901, "Indian" motorcycles (officially spelled Motocycle) were the first successful motorcycle manufacturers in the United States.[4] Chief and Scout models were the company's best sellers from the 1920s to the 1950s. The Hendee Manufacturing Company, Indian's parent company, also manufactured other products such as aircraft engines, bicycles, boat motors, and air conditioners. Though eclipsed in population by cities like Providence, Worcester, and Hartford in the early 20th century, at its outset, Springfield remained a nationally known city, in the country's top 100 cities by population, reaching a peak of 51st largest American city in the 1920 Census, comparable to the rank of New Orleans (50th) or Wichita's (51st) population ranks among American cities in 2018.[64][65] During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Springfield was known worldwide for its precision manufacturing and as "a beehive of diversified production." The American Civil War brought "intense and concentrated prosperity" to Springfield, which manufactured nearly all of the Union Army's small arms.[66] From this period until the mid-20th century, Springfield's housing stock became increasingly attractive and ornate – not only for the wealthy, but for the middle-classes – earning Springfield its nickname The City of Homes. A 1910 publication notes that "Springfield has the most beautiful homes in New England. It has the most attractive streets in New England."[67] To this day, Springfield's housing stock consists mostly of ornate, older homes, many of which would cost small fortunes to build today – Victorian "Painted Lady" mansions, elegant Queen Anne's, and Tudor style architecture dominate Springfield's housing stock; however, the city also features attractive condominiums, in particular in its urban, Metro Center neighborhood.

By the first decade of the 20th century, the City of Springfield featured over 10% of all manufacturing plants in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and a far greater percentage of its precision machinery manufacturing plants, (as opposed to textile manufacturing plants, which were more prevalent in eastern Massachusetts.) [30]

In the 1920s, the city's precision manufacturing base attracted England's Rolls-Royce, who concluded, “The artisans of Springfield – from long experience in fine precision work – were found to possess the same pride in workmanship as the craftsmen of England." From 1921 until 1931, Rolls-Royce located its only manufacturing plant outside England in Springfield. It assembled nearly 3000 Silver Ghosts and Phantoms before production was halted by the Great Depression and the decision by Rolls-Royce not to retool the plant.[68] The Rolls-Royce factory is adjacent to the former Indian Motorcycle manufacturing plant, by American International College.

Granville Brothers Aircraft manufactured aircraft at Springfield Airport from 1929 until their bankruptcy in 1934. They are best known for the trophy and speed record holding Senior Sportster ("GeeBee") series of racing aircraft.

During this time, Springfield pioneered developments in mass media. For example, the United States' first commercial radio station was founded in Springfield in 1921, WBZ, broadcasting from Springfield's most luxurious hotel, the Hotel Kimball.[4][69] Also, the United States' first UHF television station was founded in Springfield in 1953, WWLP, (which, today, is Springfield's 22 News, Working for You).

During this period, then-U.S. Vice President Thomas R. Marshall, who served under U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, famously opined, "Here is a center from which thought emanates. What is said in Springfield is heard around the world."[70]

The great floods of 1936 and 1938 and their effects[edit]

In 1936, at the height of America's Great Depression, the City of Springfield suffered one of its most devastating natural disasters prior to the tornadoes of 2011. The Connecticut River flooded, reaching record heights, inundating the South End and the North End neighborhoods, where some of Springfield's finest mansions stood. Damages were estimated at $200,000,000 in 1936 dollars.

Much of the water damage was repaired after WPA money was made available to Springfield. However, two years later, high flood waters hit Springfield again. The standing flood waters were exacerbated by the New England Hurricane of 1938, which came up the east coast of the United States on September 21, 1938.

Due to Springfield's two Great Floods, large portions of the North End and South End neighborhoods no longer exist.

During the 1960s, I-91 was constructed over the areas affected by the great floods. Several of Springfield's grandest houses, including the mansion of skating blade magnate Everett Hosmer Barney, were demolished to construct the highway. Originally, plans called for the highway to be routed along the west bank of the Connecticut River, through West Springfield; however, Springfield civic officials campaigned for it to cross the river through the North End, Metro Center, and South End neighborhoods. This decision effectively cut off the City of Springfield from the Connecticut River, its greatest natural resource.[citation needed] In 2010, plans were announced to finally reunite Springfield with the Connecticut River.[71]

Forty year decline and immigration trends[edit]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, Springfield endured a protracted decline, accelerated by the decommission of the Springfield Armory in 1969. Springfield became increasingly like the declining, second tier Northeastern U.S. cities from which it had long been set apart. During the 1980s and 1990s, Springfield developed a new reputation for crime, political corruption, and cronyism. Seeking to overcome its downgrade, the city undertook several large (but unfinished) projects, including a $1 billion high-speed rail (New Haven-Hartford-Springfield high-speed rail), a proposed $1 billion MGM Casino, and others.[72][73]

In 1968, the theretofore stalwart Springfield Armory was controversially[citation needed] closed-down amid the Vietnam War. From this point onward, precision manufacturing companies, which had long provided Springfield's economic base and were also the driving factor behind its famous creativity, left the city for places with lower taxes. (As of 2011, there are 36,300 manufacturing jobs in Metro Springfield).[74] During this time of decline, unlike its Northeast American peer cities like Providence, Rhode Island, New Haven, and Hartford, Connecticut, which hemorrhaged large portions of their populations, Springfield lost comparatively few residents. As of 2011, Springfield had only 20,000 fewer people than it did in its most populous Census year, 1960. (See population chart below). The exodus of its wealthy and middle-class – mostly Caucasians – to surrounding suburbs was compensated for by an influx of Hispanic immigrants, which changed the demographics of Springfield to a great extent by the 2010 Census. Springfield, which had once been a primarily Caucasian city, (featuring large populations of English, Irish, Italian, French Canadian, and Polish residents) with a steady 15% Black minority is now evenly split between Caucasians and Hispanics, primarily of Puerto Rican descent. Initially poor on arrival in Springfield, the Hispanic community's integration and subsequent increase in buying power set the stage for Springfield's resurgence in the first decade of the 21st century.

In addition to the influx of Latinos, as of the 2010 Census, Springfield is one of the top five most populous East Coast cities for Vietnamese immigrants – and one of the Top 3 East Coast cities for Vietnamese immigrants per capita, behind Boston and Washington, D.C. Also, the 2010 Census indicated a substantial increase in Springfield's LGBT population, likely catalyzed by Massachusetts' 2004 decision to legalize gay marriage. The 2010 Census indicates that Springfield now ranks tenth among all U.S. cities with 5.69 same-sex couples per thousand. (San Francisco, California, ranked first).[75] Since approximately 2005, Springfield's Club Quarter in Metro Center has seen a large increase in LGBT bars and clubs.[76][77]

Interstate 91 is constructed, amputating Springfield from the river[edit]

During the late 1960s, the elevated, 8-lane Interstate 91 was constructed on Springfield's riverfront – effectively blocking Springfielders' access to "The Great River." For generations, the land that became Interstate 91 was the city's most valuable land for both economic and recreational purposes. The I-91 construction also covered the mouth of the Mill River. Academics note that both rivers would present major economic opportunities if I-91 was altered.[78] In 2010, the Urban Land Institute proposed a plan for Springfield to reclaim its rivers.[71]

The original plan for Interstate 91 – detailed in the 1953 Master Highway Plan for the Springfield, Massachusetts, Metropolitan Area – called for I-91 to occupy West Springfield's Riverdale Road, (also known as U.S. Route 5), and which had been, historically, the highway used to reach Springfield from both the north and south. Indeed, between 1953 and 1958, to make way for Interstate 91, West Springfield's Riverdale Road was widened and added on to, and businesses were moved. The 1953 plan called for I-91 to connect with Springfield via several state-of-the-art bridges.[citation needed] In 1958, however, Springfield's city planners – believing that the river had become too polluted, and thus no longer useful – campaigned intensely for Interstate 91 to occupy Springfield's riverfront. They boasted that the construction of I-91 on Springfield's riverfront would catalyze economic growth comparable to that experienced during the great railroad expansion of the mid-19th century.[79] However, the highway that blocks Springfield's (now clean) rivers became the city's most famous and disastrous attempt at urban renewal.

Although West Springfield had a right and legal claim to Interstate 91, State highway officials relented to Springfield's City Planners' pressures when confronted with a technicality – a short, existing section of US 5 through West Springfield that was built during the early 1950s failed to meet Interstate design standards. Thus, the plans for I-91 were shelved in West Springfield, and hastily moved to the eastern bank of the river.

From its construction until the present, Interstate 91's design flaws have contributed to logistical problems in Springfield. Due to I-91's close proximity to both Springfield's densely built downtown and the city's rail lines and riverfront, no more than a few businesses could be built to capitalize on highway traffic. Thus, Springfield never received the promised economic benefit from I-91 – indeed, the highway's construction coincided with the start of Springfield's four decades of economic decline. Also, throughout Springfield, I-91 was constructed as an elevated highway, which blocked all riverfront views in downtown. Beneath the elevated highway, the City of Springfield's largest parking garage was constructed at 1756 spaces, as were a series of stone walls and grassy knolls, which have made the riverfront difficult to access by foot.[78][80]

The highway construction sliced through three of Springfield's most (theretofore) desirable neighborhoods and many historical landmarks – among them, Court Square, Forest Park, and the Everett Hosmer Barney Mansion. In addition, the loss of Springfield's riverfront and the ugliness of the elevated Interstate 91 contributed to white flight from the city to its suburbs.[81] Indeed, the word "stupid" has been used to describe Springfield's first, and most unfortunate attempt at urban renewal.[citation needed]

In 2010, the Urban Land Institute released a plan that proposed several different options for re-configuring Interstate 91. Currently, many Springfielders are enthused at the prospect of finally being reunited with the Mill River, and especially the Connecticut River.[71]

History of Springfield's skyline[edit]

See: List of tallest buildings in Springfield, Massachusetts

As of 2011, Springfield's skyline features relatively fewer skyscrapers than most of its peer cities. The reason for this has to do with the 1908 construction of Springfield's neo-classical 1200 Main Street building, also known as 101 State Street. The building stands at 125 feet (38 m), which, at the time of its construction, caused great controversy in both Springfield and Boston because of its "extreme height."[82] That year, the Massachusetts State Legislature set a maximum height for buildings in Springfield – at 125 feet (38 m) – the height of 1200 Main Street, and also the height of Court Square's Old First Church's steeple.[82] The only exception to this law was made for the construction of Springfield's landmark, 300-foot (91 m), Italianate, Campanile – part of the Springfield Municipal Group, dedicated in 1913 by President William Howard Taft.[83]

Springfield's building height law remained in effect until 1970, when the city's economy began to falter, and residents started to complain that Springfield looked "old-fashioned." In response to this, the city's 62-year-old building height law was abolished, and renowned architect Pietro Belluschi designed Tower Square in the brutalist, International style, popular at the time. Tower Square stands at just over 370 feet (110 m). In 1987, the Monarch Life Insurance Company constructed Springfield's 400-foot (120 m) tall), post-modern Monarch Place. During the building's construction, the Monarch Life Insurance Company filed for bankruptcy; however, the graceful, mirrored tower still bears the former company's name despite being owned by Peter Pan Bus.[84]

As of 2011, the 400-foot (120 m) Monarch Place remains Springfield's tallest skyscraper; however, the city's lack of numerous skyscrapers is now looked on as a positive trait by city advisors such as the Urban Land Institute, who write that Springfield's "Metro Center now stands out from its peers, most of which long ago demolished the human-scale architecture that made their downtowns livable." During Springfield's resurgence in the new millennium, prominent architects – like Moshe Safdie, who built the $57 million, 2008 U.S. Federal Court Building; Gwathmey Siegel & Associates, who built the $47 million, 2004 Basketball Hall of Fame; and TRO Jung Brannen, who are building the $110 million, 2012 adaptive reuse of Springfield's original Technical High School – adapted to Springfield's human-scale to a create monumental buildings rather than attempting to "achieve monumentalism through over-scaling," as has happened in other cities.[85] With energy prices rising, Springfield's 1908 building height limit now seems like an idea that was far ahead of its time.[86]

21st century[edit]

Finance board: 2004–2009[edit]

Springfield began experiencing fiscal trouble during the 1980s; however, the city's finances nearly collapsed in the first decade of the 21st century with budget shortfalls of approximately $40 million.[66] City and state officials disagreed over the crisis' causes. The State blamed overspending relative to income by the City. City officials blamed inequities in the ways additional assistance appropriations were allocated to Springfield relative to other Massachusetts cities. Both sides were correct. Springfield was overspending relative to its income, as the Commonwealth claimed. However, Springfield officials were also correct – for every $287.66 per capita in additional assistance appropriations allocated to Boston, $176.37 per capita were allocated to Cambridge, $67.50 per capita were allocated to Worcester, and a mere $12.04 per capita were allocated to Springfield.[87] Aside from overspending and gross inequities in State funding, other observers of Springfield's fiscal crisis noted a weak economy, years of incompetent management, and corruption in city government.[88]

The city's financial problems had already resulted in wage freezes for city workers, cuts in city services, layoffs, and various city fee increases; however, on June 30, 2004, the Massachusetts General Court granted control of the city (including financial, personnel, and real estate matters) to the Springfield Finance Control Board. The board was composed of three appointees by the State Secretary of Administration and Finance, Springfield's Mayor, and the President of the City Council.[89][90]

The Financial Control Board (FCB) operated under the overall direction of the State Secretary of Finance and Administration. The FCB legislation included a state loan of $52 million to be paid back with future city tax receipts.[91] A $20 million grant was originally included, but then-House Speaker Thomas Finneran eliminated that section, fearing it would invite fiscal irresponsibility among other municipalities.

The original FCB bill filed by then-Governor Mitt Romney included a suspension of Massachusetts General Law Chapter 150E, the state law that defines the collective bargaining process for public employees. (State employees are not covered by federal labor laws). Opposition from unions eliminated that section.

During the first several years of the Financial Control Board, officials concentrated on "controlling personnel costs,"[66] However, in 2006 the FCB hired the Urban Land Institute to study Springfield and then conceive a viable plan for the city's revitalization. The ULI's study and subsequent 'Plan for Springfield' resulted in significant improvements throughout Springfield's Metro Center, a dramatic citywide drop-off in crime, and a viable course for the city's continued resurgence.

On June 30, 2009, the State of Massachusetts disbanded the Finance Control Board and returned financial control to the City of Springfield

Revitalization: 2007 – June 1, 2011[edit]

From 2007 until mid-2009, Springfield pursued the National Urban Land Institute's "Plan for Springfield," which revived the city's fortunes, engendering large-scale aesthetic improvements, infrastructure investments, and construction projects. For several years, these projects renewed Springfield's traditionally robust civic pride. Despite the National Urban Land Institute's Plan's success, following the Massachusetts' Finance Board 's departure from Springfield in June 2009, the National ULI Plan was disregarded by Mayor Domenic Sarno, who purged City Hall of most of its (Boston-based) staff, which oversaw Springfield's comeback. After operating for three years without a city plan, Mayor Sarno adopted a privately funded plan known as RebuildSpringfield, which was unveiled in 2012.[92]

During the days of the National ULI Plan, Metro Center saw the construction of numerous, new buildings, (e.g., architect Moshe Safdie's $57 million new Federal Courthouse)[93] and the adaptive re-use of several historic buildings, (e.g., the $110 million adaptive re-use of Springfield's original Technical High School into Massachusetts' new, high-tech Data Center).[94][95] The North End continues to benefit from the construction of Baystate Health's "Hospital of the Future" – a $300 million, private construction project that will add over 550 new doctors to the facility – expected to be complete in 2012.[96]

Concurrently, from 2007 until 2011, numerous destination events took root in Springfield, increasing liveliness in the city. These include the annual Hoop City Jazz Festival – sponsored by Springfield-headquartered Hampden Bank – which has featured blues legend, Springfielder Taj Mahal; Springfield's new, annual Gay Pride Week, which features political discussions, films, and celebrations; and the Vintage Sports Car Club of America's new, officially sponsored race, the Springfield Vintage Grand Prix, which is held on the streets of Metro Center.[97][98][99]

Decrease in crime[edit]

Since 1997, U.S. and local crime statistics indicate that Springfield experienced a decrease in both violent crime and property crime, with both falling over 50%. Crime numbers bottomed out in 2009, increasing negligibly in 2010 and 2011.[100] Independent sources also note Springfield's decrease in criminal activity, including Morgan Quinto's annual "United States City Crime Rankings," which also show a 50% drop-off in the city's overall crime.[101][102] In 2010, Springfield ranked 51st in those rankings, in which it had once – in just 2003 – ranked 18th.[101][102]

Springfield's mature economy: healthcare; higher education; and transportation[edit]

From 2007 to 2010, Springfield prospered economically in relation to its peer cities, while enduring "the worst American economic crisis since the Great Depression."[103] Springfield is considered to have a "mature" economy, built on primarily healthcare, higher education, transportation, and to an extent, a still existent precision manufacturing center, (e.g. Smith & Wesson added 225 jobs in 2011.) [104]

Major private medical investments have included Baystate Health's $300 million "Hospital of the Future".[96] It has been reported that, on its completion in 2012, Baystate will hire 550 new doctors, approximately doubling the hospital's current capacity.[105]

In 2010, two of Springfield's most prestigious higher education institutions built multimillion-dollar facilities, which opened in 2011. Springfield College constructed a $45 million multi-purpose university center,[106] while Western New England University constructed a $40 million pharmacy school – the only such school in the region. In 2010, the University of Massachusetts Amherst moved its Urban Design graduate program to Court Square in Metro Center.[107] In early 2011, UMass Amherst announced that it would move its popular radio station WFCR to Springfield's Main Street.[108]

During Springfield's brief renaissance, the city's largest proposed monetary investment occurred in rail infrastructure – specifically, in the proposed, first-ever in the United States high-speed rail line.[109] That proposal was an approximately $1 billion investment [110] shared with the State of Connecticut and the U.S. Federal Government in the New Haven-Hartford-Springfield commuter rail line. According to NHHSRail, the project's oversight body, Springfield-New Haven high-speed commuter rail will be fully functional by 2016, featuring a northern terminus at Springfield's Union Station and a southern terminus at New Haven's Union Station.[111] It is reported that trains will reach speeds of 110 mph (180 km/h), making the Springfield-New Haven intercity commuter line the first truly "high-speed train" in the United States.[109][112] Additionally, Amtrak's Vermonter runs through downtown Springfield. The Vermonter is in the process of being re-aligned to the former Montrealer route, through the more populous Pioneer Valley cities of Chicopee and Northampton, as opposed to smaller towns like Palmer.[113]

Springfield tornado of June 1, 2011[edit]

On June 1, 2011, at approximately 4:45pm, the City of Springfield was directly hit by a tornado with wind speeds estimated at 160 mph (260 km/h), (a high-end EF3 on the Enhanced Fujita Scale), which, according to the National Weather Service, was the 2nd largest ever to have hit New England – the 1953 tornado in Worcester, Massachusetts, was slightly larger.[114] The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration called the Springfield Tornado "very significant... Noted not only for its intensity but also for the length of its continuous damage path – approximately 39 miles. The tornado was also very wide at some points, reaching a maximum width of one-half mile."[115] According to Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick, Springfielders were given only 10 minutes warning that a tornado was approaching the densely populated city. CNN delayed warning of the impending tornado due to a live interview with New York Congressman Anthony Weiner, who was discussing explicit photographs of himself that he had posted online.[116][117]

The Greater Springfield tornado left four people dead, hundreds of people suffering in hospitals with injuries ranging from lightning strikes to trauma, and over 500 people homeless in the City of Springfield alone, most of whom stayed at the MassMutual Center arena and convention center.[118][119] Over two weeks after the disaster, more than 250 people were still living at the MassMutual Center, homeless.[120]

The tornado crossed over the Connecticut River from West Springfield, Massachusetts, into the City of Springfield near the Springfield Memorial Bridge.[115] First, it caused extensive damage to Springfield's Connecticut River Walk Park, deforesting much of the park's formerly lush tree canopy and removing large sections of its attractive wrought-iron fencing.[121] Next it damaged Court Square – Springfield's historic center – ripping off parts of the Old First Church (established in 1637), and uprooting approximately half of Court Square's 200-year-old "heritage trees." Then the tornado proceeded southward down Main Street, devastating Springfield's historically Italian South End. In less than two minutes, much of the South End's commercial district – built more than a century ago and consisting of mostly brick, commercial buildings – lay in complete ruins, while the South End's recent improvements, e.g. new ornate, street lamps, were either bent or flung far from their places of origin.[122]

After devastating the South End, the tornado moved east and headed up historic Maple Street, on and around which it caused significant damage. It seriously damaged the campus of MacDuffie School. Less than a mile eastward, large sections of Springfield College and the Old Hill neighborhood were completely destroyed, as were hundreds of homes in East Forest Park, an upper-middle-class neighborhood. East Forest Park's Cathedral High School was completely ravaged by the tornado.[123] Due to the experience with these tornadoes, Springfield College's twelfth (and incumbent) president Dr. Richard B. Flynn of Omaha, Nebraska, turned a ten-month-to-a-year restoration of campus into a ten-week project. Debris from Cathedral was found roughly 43 mi (69 km) away in Millbury, Massachusetts.[124] Springfield's most suburban neighborhood – the upper-middle-class Sixteen Acres – also incurred significant damage. However, Sixteen Acres' newer homes did not weather the tornado any better than did Springfield's famous Victorians. The East Forest Park and Sixteen Acres neighborhoods remained without power for days.[119] In Springfield, the tornado completely destroyed over 100 homes, made countless others structurally unsound or uninhabitable, and caused other structures deemed hazardous to be quickly demolished.[125]

Immediately following the tornado, Governor Deval Patrick declared a "State of Emergency" for the entire Commonwealth of Massachusetts. That day, United States Senator from Massachusetts John F. Kerry cited city damages as "astronomical... well beyond tens of millions of dollars."[119] As of June 18, 2011, there have been over $140 million in tornado-related insurance claims.[126]

"Firsts" in Springfield[edit]

The City of Springfield is known as the City of Firsts because, throughout the centuries, its citizens have boldly created avant-garde products, organizations, and ideas. Today, the most famous among Springfield's "firsts" is the sport of basketball, invented in 1891 and now the world's second most popular sport. Below is a partial list of the City of Springfield's "firsts:" [127]

| Year | Notable event/development | Credited to |

|---|---|---|

| 1636 | First Springfield in the New World | William Pynchon |

| 1640 | First Accusation of Witchcraft in the New World | Mary and Hugh Parsons |

| 1641 | First Meat Packer (exporting salt pork) | William Pynchon |

| 1651 | First Banned Book in the New World | William Pynchon |

| 1777 | First Federal Arsenal | Springfield Armory, founded by George Washington and Henry Knox |

| 1794 | First Armory in the United States | Springfield Armory |

| 1795 | First American-Made Musket | Springfield Armory |

| 1806 | First American-English Dictionary | Merriam-Webster, Inc. |

| 1806 | First American Edition of the Koran[128] | Henry Brewer, printer, for Isaiah Thomas, publisher |

| 1820 | First machining lathe for interchangeable parts (leading to assembly line mass production) | Thomas Blanchard |

| 1826 | First Modern Burning Steam Carriage | Thomas Blanchard |

| 1830 | First Major American History Book | George Bancroft |

| 1834 | First Kitchen Friction Match | Chapin & Phillips Company |

| 1844 | First Vulcanization of Rubber | Charles Goodyear |

| 1849 | First Clamp-On Ice Skate | Everett Hosmer Barney (Barney & Berry, Inc). |

| 1853 | First National Horse Show in United States | |

| 1854 | First Adjustable Monkey Wrench | Bemis & Call Company |

| 1855 | First Show of School Colors | Harvard vs. Yale Rowing Race on the Connecticut River |

| 1855 | Naming of the United States Republican Party | Samuel Bowles |

| 1857 | First American Railroad Sleeping Car (also known as Pullman Car) | Wason Manufacturing Company |

| 1860 | First American Popular Parlor Game | The Game of Life by Milton Bradley Company |

| 1861 | Pocket-Size Travel Games | Game for Soldiers by the Milton Bradley Company |

| 1863 | First United States Registered Bank | National Bank of Springfield |

| 1868 | First Flat-Bottomed Paper Bag | Margaret E. Knight for Columbia Paper Bag Company |

| 1869 | First Producer of Supplementary Education Material for Kindergarten Education | Milton Bradley Company |

| 1873 | First Postcard in United States | Morgan Envelope Factory |

| 1875 | First Dog Show in United States | Springfield Rod & Gun Club |

| 1877 | First Social Service Agency in United States | Union Relief Association |

| 1878 | First Commercial Telephone Toll Line (from Springfield to Holyoke)[129] | Springfield Telephone and Automatic Signal Company |

| 1881 | First Planned Residential Neighborhood | The McKnight Historic District; John and William McKnight |

| 1882 | First Music Appreciation Course | Springfield Public Schools |

| 1886 | First Revolver Club | Springfield Revolver Club, organized by Smith & Wesson[130] |

| 1891 | First Game of Basketball | Dr. James Naismith of Springfield College |

| 1893 | First Gasoline-powered Automobile | Charles E and J. Frank Duryea |

| 1899 | First Public Swimming Pool in United States | Forest Park |

| 1901 | First Successful Motorcycle | Indian Motocycle |

| 1902 | First Window Envelope | U. S. Envelope Company |

| 1905 | First Modern, Motorized Fire Engine | Knox Automobile |

| 1907 | First Modern, Motorized Fire Department | Springfield Fire Department |

| 1910 | First Camp Fire Girls | Charlotte Guilick |

| 1911 | First Factory Air Conditioning | Bosch Magneto Company |

| 1911 | First Measuring Gasoline Pump[131][132] | Gilbert & Barker Manufacturing Company (Gilbarco) |

| 1912 | First Agricultural Course | Hampden County Improvement League |

| 1912 | First Physical Education Course | International Y. M. C. A. College (Springfield College) |

| 1912 | First Basketball | Victor Sporting Goods Company of Springfield |

| 1918 | First American Military Regiment Decorated by a Foreign Power (France, with Croix de Guerre) | 104th Infantry Regiment |

| 1918 | First Community Chest | |

| 1919 | First Junior Achievement Program | Horace A. Moses |

| 1920 | First Rolls-Royce American Automobile Plant | Frederick Royce |

| 1921 | First Commercial Radio Station in United States | WBZA; located at The Hotel Kimball |

| 1928 | First Experimental Airplane-Motorcycle Courier Service (Holyoke-Northampton-Westfield-Springfield-Hartford)[133] | United States Post Office Department, with Indian Motorcycles |

| 1930 | First Test Market for Frozen Foods | Clarence Birdseye |

| 1936 | First Standard-Issue Semi-Automatic Military Rifle[134] | M1 Garand by John Garand for Springfield Armory |

| 1937 | First American Built Planetarium | Springfield Science Museum |

| 1939 | First Fluorescent Lighting System Installation | Springfield Armory |

| 1949 | First American Discount Store | King's |

| 1953 | First UHF TV Station in United States | WWLP-22News |

| 1954 | First Municipal Council on Aging[135] | Springfield Council on Aging/Elder Affairs |

See also[edit]

- The Springfield Plan

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Springfield, Massachusetts

- Notable residents of Springfield, Massachusetts

References[edit]

- ^ "Find in a library: The encyclopedia of New England". Worldcat.org.

- ^ a b "New Museum of Springfield History to Open October 10 — News". Springfield Museums. September 24, 2009. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ "The Gun that Won the West". Turner Classic Movies.