A Guide to Beer, Food and History in Somersworth

Spend a day in this under-explored Seacoast town

The view of Great Falls in this painting was from the perspective of the high school building, as noted in the seal below the image, dated 1856. Photo Courtesy American Textile History Museum

As a kid, I wore coats made from wool fabrics that my mother bought at the Baxter Woolen Mills in Somersworth. We used to ride the bus from neighboring Dover, and I would choose the color of next winter’s coat from the mill store. The mill store is long gone, and the mill is now turned into apartments, but like Dover’s, the mills were central to Somersworth’s story.

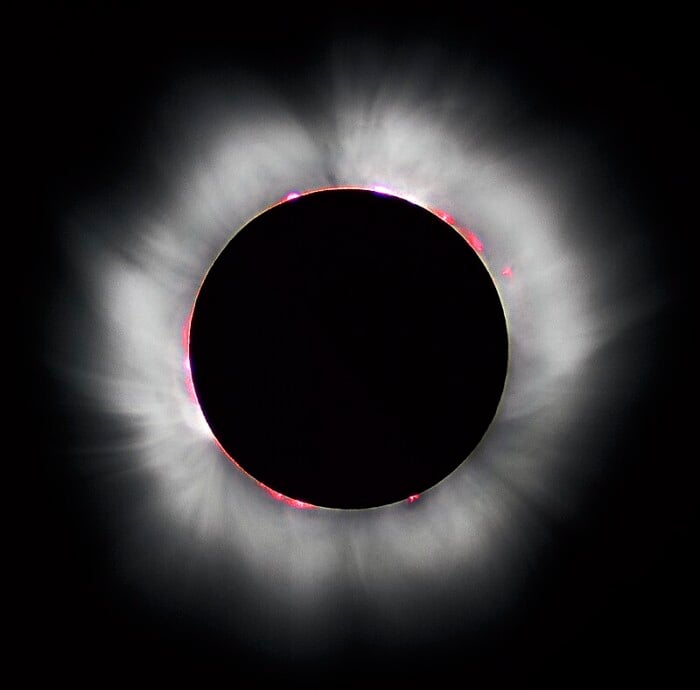

Originally part of Dover, the settlement alongside the Salmon Falls River had become prosperous enough by 1729 to support its own meetinghouse and minister, forming the parish of Somersworth. The Great Falls, with its 100-foot drop, was the source of power for a grist mill and other small mills, and would become the basis for the town’s livelihood and growth.

The grist mill and land along the falls — including what is now Market, Main and High streets — was bought by Isaac Wendall, who was already manufacturing cotton fabrics at the Cocheco Falls in Dover; he opened Mill No. 1 of the Great Falls Manufacturing Company in 1823. The company would eventually grow to seven along the river, producing woolen fabrics; an eighth, The Bleachery, turned the natural wool into pure white so it could take dyes.

Many of the former Great Falls Manufacturing mills are now apartments. Photo by Stillman Rogers

The company donated the land for three Protestant churches and sold off the area of the city’s current downtown. They built tenements for worker housing, improved the streets, started a fire department, and built a city reservoir. Other industries opened and flourished: a shoe factory in 1880, the makers of the popular White Mountain Stoves, and Great Falls Woolen Company, farther down the river near The Bleachery.

Over the decades, mills closed and new ones took their place. In 1941, Charles E. Baxter Sr. bought the empty 1865 four-story brick building and several smaller ones owned by the Deering Milliken Company, which had closed during the Depression, and opened Baxter Woolen Mills. His son, Charles E. Baxter Jr., who later became its vice president of manufacturing, recalls the mill, where he began working summers when he was in high school: “It was a fully integrated mill that included blending and carding, spinning, weaving, dyeing and finishing. The original water wheels were defunct, and very large electric motors drove overhead shafting on the four floors, with leather belting to drive the individual machines.”

In World War II, Baxter explains, existing mills had turned to producing for the war effort, making cloth for clothing scarce, so the new mill stepped up to fill the demand. “During the early years, most of the cloth was made for men’s outer wear, such as jackets and overcoats.” As business expanded for women’s wear in the 1950s, the company bought a mill in East Rochester, where they were able to increase capacity. The Somersworth mill closed in 1958 and a portion of it was destroyed by fire in 1973; the remaining building is now apartments, with the Baxter Woolen Mills name still across its top.

Other mill buildings that make up much of Somersworth’s urban landscape have also found other uses, and like many former mill cities, Somersworth continues its effort to revitalize its downtown. For more on the downtown architecture — several striking buildings caught our attention as we explored — I turned to local historian Jenne Holmes, who writes the weekly “Simply Somersworth” feature for Foster’s Daily Democrat in Dover, a delightful column that ties today’s news with the city’s history.

She told me that the large red Victorian building with gables was originally the Great Falls National Bank, and the prominent brick building at the corner of High and Highland streets was built in 1889 as the Grand Army of the Republic Hall, home of the Civil War veterans organization.

The 1899 white church on High Street is now owned by the Somersworth VFW, which has invested in its preservation. Its 16 stained glass windows are the originals, and the louvres in its copper-domed spire conceal Verizon antennae. The former railway depot is now a restaurant, Gravy, owned by seacoast chef Mark Segal.

The Somersworth Historical Society Museum at 157 Main St. is filled with photos and artifacts from Somersworth’s past, with rooms devoted to schools, churches, the military, mills and more — including an antique peanut-roasting machine invented in Somersworth.

The former train depot is now the Gravy restaurant. Photo by Stillman Rogers

While the mill workers were predominantly from Quebec, and French was heard as commonly as English on Somersworth streets, the culture that’s making news in Somersworth today is that of its Indonesian population. More than 2,000 people are from Indonesia or of Indonesian descent, and they make up 18% of the city’s population. This is reflected in three restaurants and the Indonesian Cultural Center, which opened with a festival in May of this year.

A sign and banner welcome visitors to the nation’s first “Little Indonesia” district, a project supported by the Indonesian ambassador to the U.S. to promote Indonesian culture and businesses and increase tourism. Future plans include painting the neighborhood’s crosswalks in traditional batik designs.

Of course, we headed to the nearest Indonesian restaurant, Tasya’s Kitchen, a tiny place with a few tables and a full-color menu that has photos and good descriptions of each dish. We split the “Tour of Indonesia,” a sampler plate that included eight different dishes and jasmine rice. Some dishes — bamboo skewers of grilled chicken with peanut sauce, curried chicken, spring rolls with shrimp and bamboo shoots — are familiar; others, less so. Beef rendang, for example, is an aromatic beef slow-cooked in coconut milk, and nasi gudeg is based on jackfruit, rarely encountered here. It has a texture similar to pulled pork and is seasoned and served in the same way.

Tasya’s Kitchen is not the only Indonesian restaurant here. Bali Sate House is outside the downtown center, in the part of Somersworth that seems to blend into Dover near the Spalding Turnpike intersection. It’s larger, with more tables, but the same casual un-fancy atmosphere where the food outshines the frills. Indo U.S. Cuisine on Main Street serves both Indonesian and traditional American comfort foods in diner-like surroundings.

Isaac Wendall, who built the first mill complex, was a strong temperance man (Teatotaller, a High Street café and bakery, gives this legacy a nod), and under his edict, Somersworth was a “dry town.” His influence didn’t prevail long though, and in 1895 a bottling company was opened here, for beer and ale produced by Frank Jones in Portsmouth and brought in barrels by train. Prohibition ended that, but the tradition has been revived by three local craft breweries: Stripe Nine Brewing, Bad Lab Beer Co. and Earth Eagle North.