The Woman Who Led Kamala Harris to This Moment

How Harris’s mother paved the way for her barrier-breaking candidacy

/media/video/upload/KamalaHarris2_NSCzVsW.mp4)

Sharon McGaffie was used to a full house. One evening in early 1969, her cousin Aubrey LaBrie did what he would often do—he brought over a handful of his friends to her West Berkeley duplex. Her home would turn into an impromptu hub for young, Black intellectuals, a place for them to have friendly squabbles over the latest news, which at the time was dominated by the civil-rights struggle and the newly elected president, Richard Nixon. McGaffie, then just a teenager, would do her homework while her mother and another cousin whipped up a pot of Louisiana gumbo, a family favorite.

But that night, there was someone new whom McGaffie had never seen before: a tiny, sari-clad woman named Shyamala Gopalan. “She stood out a little bit because she was Indian,” McGaffie said. But Gopalan didn’t seem to feel out of place. She joined in on the debates and, at one point, went to the kitchen and struck up a conversation with McGaffie’s mother. “She fit right in,” LaBrie told me.

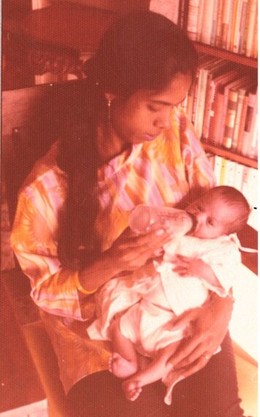

Gopalan spent much of her life fitting in where she wasn’t supposed to. When she left India in 1958 to pursue a graduate degree at UC Berkeley, she was one of the few Indian women enrolled at the university. In fact, the 19-year-old was one of the few Indian women in the entire country. Five years later, she bucked the Indian tradition of an arranged marriage and fell for a budding economist named Donald Harris. They named their first daughter after the Sanskrit word for “lotus”: Kamala.

The first Black and South Asian woman on a presidential ticket, Kamala Harris has repeatedly invoked her mother, who passed away from colon cancer in 2009, in embracing the historic nature of her candidacy. Harris, who declined multiple requests for comment for this story, brings up Gopalan so often on the campaign trail that their relationship has become a recurring theme of her candidacy: In her speech at the Democratic National Convention in August, she called her mother “the most important person in my life,” an inspiration on par with women such as Fannie Lou Hamer and Shirley Chisholm. “There’s another woman … whose shoulders I stand on,” she said. “And that’s my mother, Shyamala Gopalan Harris.” During the vice-presidential debate earlier this month, she noted all the barriers she was breaking as Joe Biden’s running mate and said that Gopalan “must be looking down on this.” Even her Secret Service code name, Pioneer, is a wink and a nod to her background.

But years before Harris was even born, Gopalan was breaking through her own barriers. Her attitude was “This is who I am,” says Lenore Pomerance, one of Gopalan’s lifelong friends, who met her in 1961. It’s a mentality that seems to have followed Harris from her childhood in Berkeley to the cusp of entering the White House. “Don’t let people tell you who you are,” Gopalan told her. “You tell them who you are.”

The daughter of a high-ranking bureaucrat under the British raj, Gopalan had a comfortable childhood. She was born in the southern city of Madras, now Chennai, but her father’s work took the family to Bombay, Kolkata, and New Delhi—where Gopalan spent most of her formative years. When she was 9 years old, India broke free from British colonial rule. A year later, Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated. After India gained independence in 1947, her father, P. V. Gopalan, led the resettlement of refugees fleeing current-day Bangladesh for India.

Those experiences helped shape Gopalan’s sense of what was possible. She got a bachelor’s degree in home science—which in India was meant to groom women for domesticity—before deciding that she wanted to become an actual scientist. But at that time, few Indian women went to graduate school. Even if Gopalan wanted to, Indian students generally chose a career track by the end of high school, and switching gears would have been difficult, if not impossible.

She got word of a doctoral program at Berkeley in nutrition and endocrinology, and applied. “When Shyamala wanted to go to California, [my father] said, ‘Go ahead,’” Gopalan Balachandran, Shyamala’s younger brother, told me. “He left his home [as a young man] and came to Delhi to work on his own without knowing anybody. So he had no problem with Shyamala going.”

Even for an upper-caste family like Gopalan’s, that was remarkable. India is deeply patriarchal today, even more so when Gopalan left for Berkeley. Literacy rates for women significantly lag rates for men, and sex-selective abortion, though technically illegal, is still common. Not unusual for Indian women of the era, Gopalan’s mother never attended high school. Sixty years ago, sending her daughter thousands of miles away to pursue an education abroad was exceptionally progressive.

But although deciding to leave her family behind in India was hard enough for Gopalan, coming to the United States as a teenager wouldn’t have been any easier. Indian Americans now number about 4 million, giving many new immigrants a built-in community they can fall back on, but Gopalan arrived at a time when discriminatory immigration laws placed severe quotas on Asian immigrants: The number of Indians allowed to move to the U.S. was capped at 100 people a year. Gopalan became one of just 12,000 Indian Americans living in the country, the majority of them men. Those who were here faced significant racism; McGaffie told me that Gopalan felt discriminated against at work. “Every woman coming from India at that time was a little bit of an outsider,” says Anirvan Chatterjee, an amateur historian of South Asians in Berkeley.

When Gopalan arrived, Americans were protesting everything—racial injustice, imperialism, the Vietnam War—and Berkeley was at the center of it all. Gopalan was all in.

In 1960, when Black students in North Carolina staged a high-profile sit-in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter in protest of Jim Crow, Gopalan joined a sit-in at the local Woolworth’s as a display of solidarity. She also joined a group of Black students who met regularly to study the works of Black writers such as W. E. B. Du Bois and Ralph Ellison. The group, known as the Afro American Association, helped establish the field of Black studies at colleges nationwide and provided much of the intellectual firepower for the Black Panther Party. “It was an incubator for Black consciousness and Black power,” said LaBrie, who was also involved. Gopalan was the only non-Black member.

It was through her civil-rights activism that she got to know Donald Harris, a fellow Berkeley grad student from Jamaica. Harris was giving a talk at an event off campus, and when he finished, Gopalan introduced herself. The two started dating and married a few years later. “They just went to the courthouse on their lunch hour,” Lenore Pomerance told me. The couple had two daughters, Kamala and then Maya, who is now an attorney and a top adviser to her sister.

In eschewing an arranged marriage and choosing a Black partner, Gopalan had lit a match under convention and blown it up. Anti-Black racism and colorism are pervasive in India and across the diaspora: When a 2012 poll from the Pew Research Center asked Indian Americans how well they get along with African Americans, nearly a quarter responded “not too well or not at all well.” Just 7 percent said the same about white people. Gopalan’s relationship with Harris “was definitely groundbreaking,” says Sooni Taraporevala, who wrote the screenplay for the film Mississippi Masala, in which an Indian woman falls in love with a Black man. “When we did Mississippi Masala, it was in the 1990s. And even then, it was extremely rare.”

In the 1960s, it was a scandal in India. Balachandran, Gopalan’s brother, said that his parents were hurt and disappointed about the marriage, but that their reaction wasn’t about race. “They had not met the bridegroom before” the wedding, he told me. “I don’t think they had any issues that he was Jamaican or anything like that.” But Gopalan believed that not all Indians would be accepting. “I heard her talk about how she could not take her girls back [to India] because she married outside of her race and she married a Black man,” said McGaffie, whose mother often took care of Kamala and Maya after school.

In 1971, Gopalan filed for divorce. If her marriage was cause for controversy, her divorce was no less so. India has among the lowest divorce rates in the world in part because of the intense stigma around it, especially for women. Harris’s own description of the divorce suggests that it was a difficult moment for her mother, and a source of family strife. “I think, for my mother, the divorce represented a kind of failure she had never considered,” she wrote in her memoir, The Truths We Hold. “Her marriage was as much an act of rebellion as an act of love. Explaining it to her parents had been hard enough. Explaining the divorce, I imagine, was harder. I doubt they ever said to her, ‘I told you so,’ but I think those words echoed in her mind regardless.”

Harris talks about her mother all the time. She often mentions how her mom would bring her along to protests “strapped tightly in my stroller.” She has devoted an entire campaign video to Gopalan and credits her for instilling “in my sister, Maya, and me the values that would chart the course of our lives.”

One of those values was a refusal to be boxed in by societal expectations. Gopalan never hewed to other people’s notions of where she did and didn’t belong, and she was explicit that her daughters should do the same. “If you don’t define yourself,” she would often tell them, “people will try to define you.”

By the time she divorced, Gopalan had completed her doctorate and was working as a cancer researcher at Berkeley. She retained custody of Kamala and Maya, who saw their father, a Stanford University professor, on weekends and during summers off from school. When Harris was 12 years old, Gopalan accepted a job at McGill University, and the family moved to Montreal.

Gopalan was a devoted and fiercely protective parent: She volunteered in her daughters’ classrooms and would always keep the house stocked with freshly baked cookies. But as a single mother, she had little tolerance for frivolity. In the mornings, she’d give her daughters breakfast drinks or Pop-Tarts because, as Harris has written, “breakfast was not the time to fuss around.” When Kamala or Maya came home upset from something that had happened at school, Gopalan made them reflect on their own culpability, asking, “Well, what did you do?” And she was blunt about the challenges her kids would face as biracial children. “She didn’t talk little-kid talk,” McGaffie said. “She had real conversations with them.”

The family traveled periodically to visit relatives in India, where Harris would take long walks along the beach with her grandfather and learn how to pray at a Hindu temple. At home, Gopalan would cook up Indian meals such as dal, idli, and bhindi ki sabzi. But even after the divorce, Gopalan was keen on raising her daughters as Black. Kamala and Maya sang in the children’s choir at a Black Baptist church. On Thursday evenings, “Shyamala and the girls,” as the trio were known around the neighborhood, were familiar faces at Rainbow Sign, a Black cultural center in Berkeley. Her mother, Harris has written, “knew that her adopted homeland would see Maya and me as black girls, and she was determined to make sure we would grow into confident, proud black women.”

It was an unlikely choice for an Indian at the time. “It’s not that she didn’t give a damn,” LaBrie said. “But this is the way she’s conducting her life, and if nobody agrees with you, so be it.” Years later, Harris herself would sound almost exactly the same note: “I am who I am. I’m good with it. You might need to figure it out, but I’m fine with it.”

Harris’s approach to politics today as the just-maybe next vice president has traces of her mother’s influence. Although Democrats are torn between progressives and moderates, Harris is one of the few leaders in her party whose politics don’t neatly align with either camp. During her time as a prosecutor in San Francisco, and then as California’s attorney general, Harris wasn’t exactly a paragon of progressivism: She rejected a request for additional DNA testing that could have exonerated a man on death row and resisted calls from local activists to investigate police shootings of Black men, moves that have irked leftists.

Though she’s tacked to the left in recent years—in 2019, she had one of the most liberal voting records in the Senate—she opposes Medicare for All and has kindled a warmer relationship with Silicon Valley than most other progressives. During the Democratic primary, when the left-wing stalwarts Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren were centering their campaigns on a “political revolution” and “big structural change,” Harris told The New York Times that she’s “not trying to restructure society.”

“She sort of defies being labeled,” Ron Hayduk, a political scientist at San Francisco State University, told me. “She has taken positions that are not one or the other. It’s both/and, not either/or … It has also led some voters to question the authenticity of her convictions. People have said she’s trying to have it both ways.”

Harris’s self-proclaimed tendency to “reject false choices” didn’t seem to help her during her own bid for the presidency: She dropped out of the race even before voting got under way. “She was trying to be in the middle,” Hayduk said, “but who cares about that person in the middle who is trying to go from one lane to the next?” However, the fact that Harris isn’t tightly linked to any one of the party’s ideological poles may have been exactly what made her an enticing vice-presidential pick for Biden.

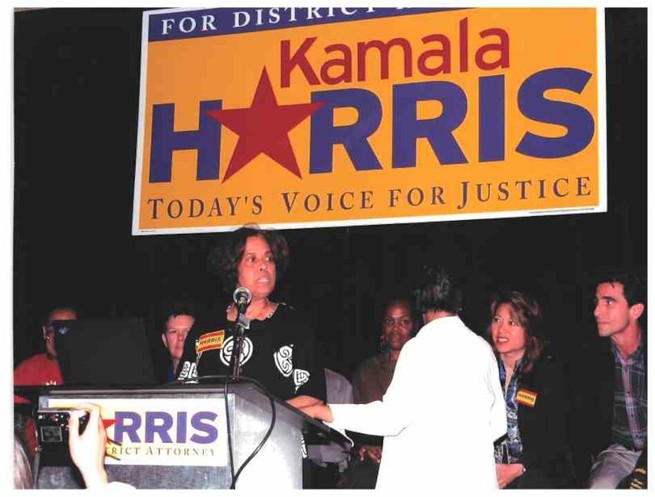

Gopalan is no longer around to tell Harris to ignore other people’s expectations, but the potential vice president likely wouldn’t be in this spot without her. Following in the footsteps of her mother, Harris staged a protest as a middle schooler in Montreal, demanding the right to play soccer in the courtyard of their apartment complex. “I’m happy to report that our demands were met,” Harris wrote of the incident. When Harris mounted a long-shot run for San Francisco district attorney in 2003, Gopalan was an integral part of her campaign, chauffeuring her to events, directing volunteers, and drumming up support for her daughter’s candidacy. There was no lawn her daughter couldn’t play on, no office she couldn’t hold.

“I keep thinking about that 25-year-old Indian woman—all of 5 feet tall—who gave birth to me at Kaiser Hospital in Oakland, California,” Harris said during her speech at the Democratic National Convention. “On that day, she probably could have never imagined that I would be standing before you now speaking these words: I accept your nomination for vice president of the United States of America.” But throughout her life, Gopalan had continually expanded the notions of what was possible: That her daughter would one day reach the upper echelons of American politics may be just the kind of thing she would have imagined.