The role of sequencers in electronic music, pop, and hip-hop can’t be overstated. They have played a vital function, allowing musicians to program complex melodies, bass lines, and drum programs and to play them through numerous synthesizers and drum machines simultaneously — turning their synth rigs into full-fledged synth orchestras. Sequencers have birthed entire musical languages from the ostinato-laden synth scores of the 1980s to the hypnotic, squelching bass perambulations of ’90s acid house.

These days, most professional and amateur producers use their DAWs for sequencing software and hardware instruments. But there’s something inspiring about hardware and early software sequencers: a hands-on, tactile interaction that can engage you in a different way than your DAW’s piano roll.

Let’s take a brief tour of the history of sequencers, starting with the very earliest incarnations, and explore some standout examples of the most influential analog, digital, and software sequencers from the latter half of the 20th century.

Earliest Sequencers

It might surprise you to learn that the dawn of sequencers stretches back centuries. In fact, some of the first documented musical sequencers showed up in the 1600s, striking bells tuned to musical notes inside of cuckoo clocks. Clockmakers were also responsible for adapting their clockworks into sophisticated music boxes in the 18th century, with automated clockwork organs following shortly after.

The player piano was another prototypical music sequencer. The Pianola, the first mass-market player piano, hit the scene at the tail end of the 19th century, and it was capable of simultaneously playing up to 65 notes from songs “sequenced” or punched onto 11.25-inch paper rolls. The term “piano roll” as it applies to the sequencing display in today’s DAWs actually derived from early player pianos.

Analog Sequencers

Leaping forward to the modular-synthesizer boom of the 1960s, sequencers provided a way for synthesists to perform multi-part arrangements using their massive modular rigs.

In 1964, Bob Moog unveiled his first modular voltage-controlled synthesizer, which became commercially available in 1967 with the Moog Synthesizer 1c. In 1968, Moog added the 960 Sequential Controller to his complement of synth modules. The 960 was an 8-step sequencer with three pattern lanes, which could be chained via the 962 Sequential Switch to create patterns of up to 24 steps.

Concurrently, Don Buchla, the father of West Coast synthesis, released the Buchla System 100. Whether the Buchla System 100 or the Moog modular came first is up for debate since they essentially dropped at the same time. However, in terms of sequencers, Buchla beat Dr. Moog to the punch in 1964 by including options for both an 8-step sequencer module (123 Sequential Voltage Source) and a 16-step sequencer module (146 Sequential Voltage Source) for the Buchla 100 series modular systems. Like the Moog 960, the Buchla 123 and 146 modules offered three pattern lanes for sequencing multiple voices or modulators.

Alan R. Pearlman and the gang at ARP Instruments, Inc. joined the sequencer party in 1970 with the 1027 Clocked Sequential Control, a 3 x 10-step sequencer for their venerable 2500 modular system. ARP also released the standalone 16-step ARP Sequencer in the 1970s for use with the 2500 modular system, the 2600 semi-modular synthesizer, the Odyssey duophonic synthesizer, and synthesizers from Roland, Sequential Circuits, and Oberheim.

These early step sequencers were fully analog, relying on voltage to affect changes in pitch and modulation parameters. They were relatively straightforward to operate but certainly limited when compared to the digital sequencers that would largely replace them in the 1980s. However, analog step sequencers are experiencing something of a renaissance due to their inviting workflow and, counterintuitively, their limitations, which some synthesists argue amplify rather than hinder their creativity.

Digital Sequencers

Digital sequencers were introduced in the 1970s. Early devices included the Electronic Dream Plant Spider, a 252-step digital sequencer, designed by Oxford University engineering technician Steve Evans and Chris Huggett, who was responsible for the creation of the EDP Wasp and contributed to the design of the OSC OSCar, the Akai S1000 sampler, and the Novation Bass Station and Supernova. The EDP Spider was followed by the EMS Sequencer series, the Oberheim DS-2, the Sequential Circuits Model 800, and the Roland MC-8 Microcomposer, the world’s first standalone microprocessor-driven music sequencer.

In contrast to their analog counterparts, digital sequencers allowed users to generate very long sequences, from the Spider’s 252 steps to the Roland MC-8’s 5,200 steps of polyphonic sequencing. Plus, you could store a limited number of patterns for recall. However, these devices still outputted CV/gate information, meaning they could be used with existing analog modular systems, semi-modular synthesizers, and performance synthesizers from Moog, Roland, Korg, Sequential Circuits, and more.

Following the introduction of MIDI in 1982, Roland released the first MIDI sequencer: the Roland MSQ-700. The MSQ-700 allowed for both polyphonic step sequencing and keyboard recording, meaning you could record full live passages of MIDI from a keyboard controller (using an onboard metronome to keep time) and send it to any connected synth, with the ability to send unique sequences to up to eight instruments from a single device. It also provided quantization (referred to by Roland as “time correction”) for fixing flubbed notes, and it could store sequences offline by printing sequence data to a cassette tape! These specs seem quaint compared to the MIDI capabilities of any modern DAW, but, for the time, they were revolutionary; and the MSQ-700 had many adherents, including Dave Stewart of Eurythmics.

By the mid-1980s, the market was awash in digital sequencers, including popular models from Yamaha, Alesis, and the other aforementioned manufacturers. And digital sequencers were ubiquitous on the drum machines that helped define the sound of the 1980s from the legendary LinnDrum to Roland’s TR series, the E-mu Drumulator, the Sequential Circuits DrumTraks, and others.

In 1988, Akai released its first MIDI Production Center: the Akai MPC-60. Designed by Roger Linn, the MPC-60 was a sequencer, sampler, and performance instrument all in one. As pivotal as the early Moog modular systems and the Roland TR-808, the Akai MPC-60 revolutionized hip-hop and pop and laid the groundwork for modern production workstations such as the Native Instruments Maschine MK3 and Maschine+, the Elektron Analog Rytm MKII, and the Ableton Push 2.

Software Sequencers

While digital hardware sequencers were maturing, so, too, were software sequencers. Released in 1979, the Fairlight CMI — an outrageously retro-futuristic production workstation and sampler — provided a proof of concept for software sequencers. Of course, the Fairlight CMI was wildly expensive, so it was only available for use by a select few. However, as personal computing power increased, it opened the door for more people to take advantage of the potential of software sequencing. In 1983, Yamaha introduced music-production modules for MSX (an early standard computer architecture), and Roland brought sequencing and synthesis to the PC, Apple II, and Commodore 64 with their CMU-800 sound module. Just one year later, Roland released the MPU-401, the first MIDI sound card for PC, prompting a massive shift in the industry toward “in-the-box” MIDI-based music production that continues today inside every DAW.

Another interesting development in software sequencers was the phenomenon of music trackers. Trackers were sample-based music-production tools that first popped up on the Amiga platform in 1987, and they presented a unique way of sequencing music in a computer environment. Known for their vertical-column design and hexadecimal coding system used for programming sequences and manipulating parameters, trackers gained a cult following among electronic music producers who enjoyed the vertical workflow and rather expansive options for sample manipulation.

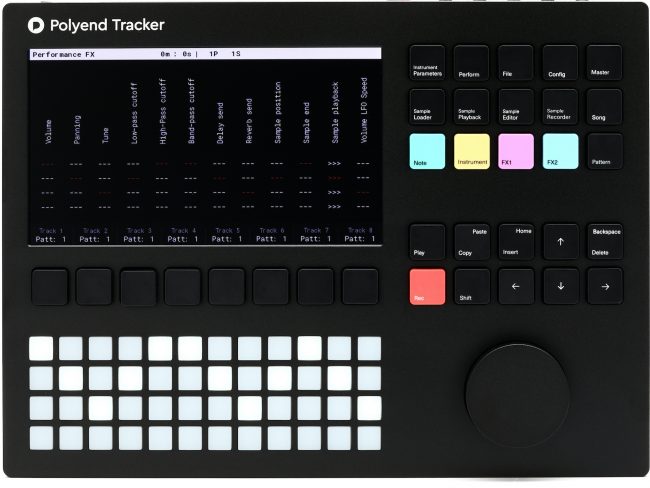

For those interested in trackers, modern clones of the original trackers, such as the FastTracker 2, are available. Another well-regarded option is Renoise, which has had a steady following since its release in 2002 and continues to update its capabilities. But, for a truly unique tracker experience, check out the Polyend Tracker, which transports the tracker format into a standalone hardware unit.

The Sequencer Renaissance

As mentioned, hardware sequencers are currently having a moment, and Sweetwater has many fun and inspiring sequencers to spark your creativity. Eurorack aficionados will enjoy these sequencers from Arturia: the 37-key KeyStep Pro and the BeatStep Pro, which offers two independent 64-step sequencers and a 16-track drum sequencer and is equipped with the connectivity you need to integrate your Eurorack modules. For large synth setups, we recommend the Polyend Seq 8-track, 32-step hardware sequencer and the Korg SQ-64 polyphonic sequencer. However, if you’re committed to “in-the-box” sequencing, then Ableton Live 11 is a great choice with a robust set of built-in MIDI effects. For non-Live users, check out Sugar Bytes Thesys, a fast, intuitive, and comprehensive software sequencer that works with any DAW.

For questions about sequencers or any other electronic music-production tools, please contact your Sweetwater Sales Engineer at (800) 222-4700. They’re here to hook you up with the right gear to inspire your music making!